This story originally appeared on City Lab and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

Global leaders gathered in Paris on Wednesday for the second working day of COP 21, the U.N. Climate Change Conference. Outside the main working sessions, leaders from across nations and sectors spoke on resilience, or how communities, cities and nations prepare for and bounce back from climate shocks.

It's a tricky task. While some parts of the world are already experiencing indisputable effects of climate change, for much of the world the climate future remains diffuse and complex. How do you prepare for the unknown?

What El Niño brings

There is a shorter-term global climate event that may offer insight into what that new normal will be. El Niño is the primary driver of extreme weather conditions year-to-year, all over the world. The natural, cyclical climatic phenomenon is marked by warm surface waters collecting along the coast of South America and a rise in atmospheric temperatures, affecting global weather patterns.

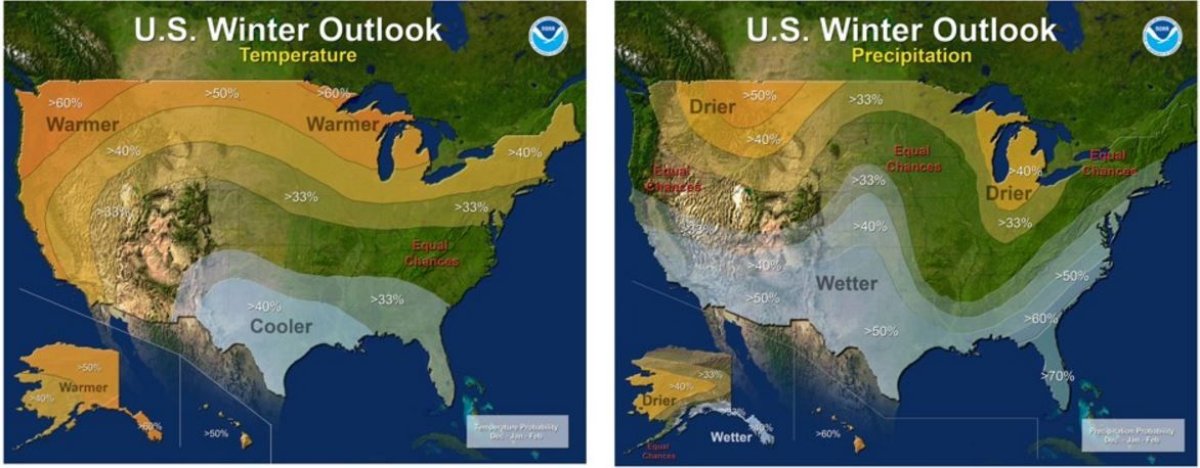

This winter, scientists believe we're in for the strongest El Niño since 1998—or possibly on record. You may have heard the most about it in the context of California, where southern parts of the state often receive heavy rainfall during strong El Niño years. (There is virtually no way it will be enough to resolve the statewide drought.) The Midwestern and Northeastern U.S. will likely see a milder winter than it would otherwise.

Meanwhile, parts of Australia and Asia will get drier—the uncontrollable wildfires in Indonesia have been linked to El Niño-related drought—while much of Central and South America will get torrents of rain. Southern and eastern parts of Africa are in for harsh El Niño floods and droughts. Fishing, agriculture and marine life will take a hit. Health risks and food shortages, especially in already-vulnerable countries, will likely be exacerbated.

Links to climate change

Human-induced climate change is also causing increased global temperatures and a range of extreme weather (and health) conditions all over the world. From a local perspective, not all of El Niño's effects will likely be the same kind as those we'd expect from climate change; as WPR reports, in the Midwestern U.S., El Niño is forecasted to bring a warmer and slightly drier winter than usual, while the climate-change projection is warmer and wetter. The two are separate phenomena.

However, with 2015 likely clocking in as the warmest year on record, this year's El Niño conditions will be starting from a very different-looking planet than in years past. We have higher atmospheric temperatures, warmer oceans and far less Arctic ice and snow cover than we did in 1998, the year of the last major El Niño.

"So this naturally occurring El Niño event and human induced climate change may interact and modify each other in ways which we have never before experienced," World Meteorological Organization Secretary-General Michel Jarraud said in a press release.

It's hard to say how everything will play out, exactly. Since each El Niño is distinct, and there are relatively little data tracking past occurrences, future events are exceptionally hard to model. In some places, El Niño's storm surges may wreak even more destruction on coastlines with already-high sea levels brought on by climate change. Elsewhere, like in the Midwest U.S., El Niño may sort of "counteract" the expected effects of climate change—but again, it's hard to know for sure, especially when you throw other weather variables into the mix.

Scientific understanding of how the two phenomena affect each other is still in its infancy.

A glimpse into the future

Despite the unknowns, policy leaders concerned with resilience to climate change should be paying attention to whatever happens this season. Assuming El Niño maintains its strength, this year's warmer winter could be a sneak-peek at what weather will be like, long-term, in some parts of the world.

"I think that's a perfectly valid analogy, but if it's really warm this winter because of El Niño, it's warm for a different reason," Dan Vimont, a professor of atmospheric and oceanic sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, told WPR. "In the future, this could be a normal winter, and an El Niño winter could be even warmer."

The good news: Many governments and global organizations are better equipped to minimize El Niño's human impacts than they have been in the past. But to protect the world from the worst climate effects of any origin, the best form of preparation will be an iron-clad, universal agreement from COP21 to cut back global warming.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.