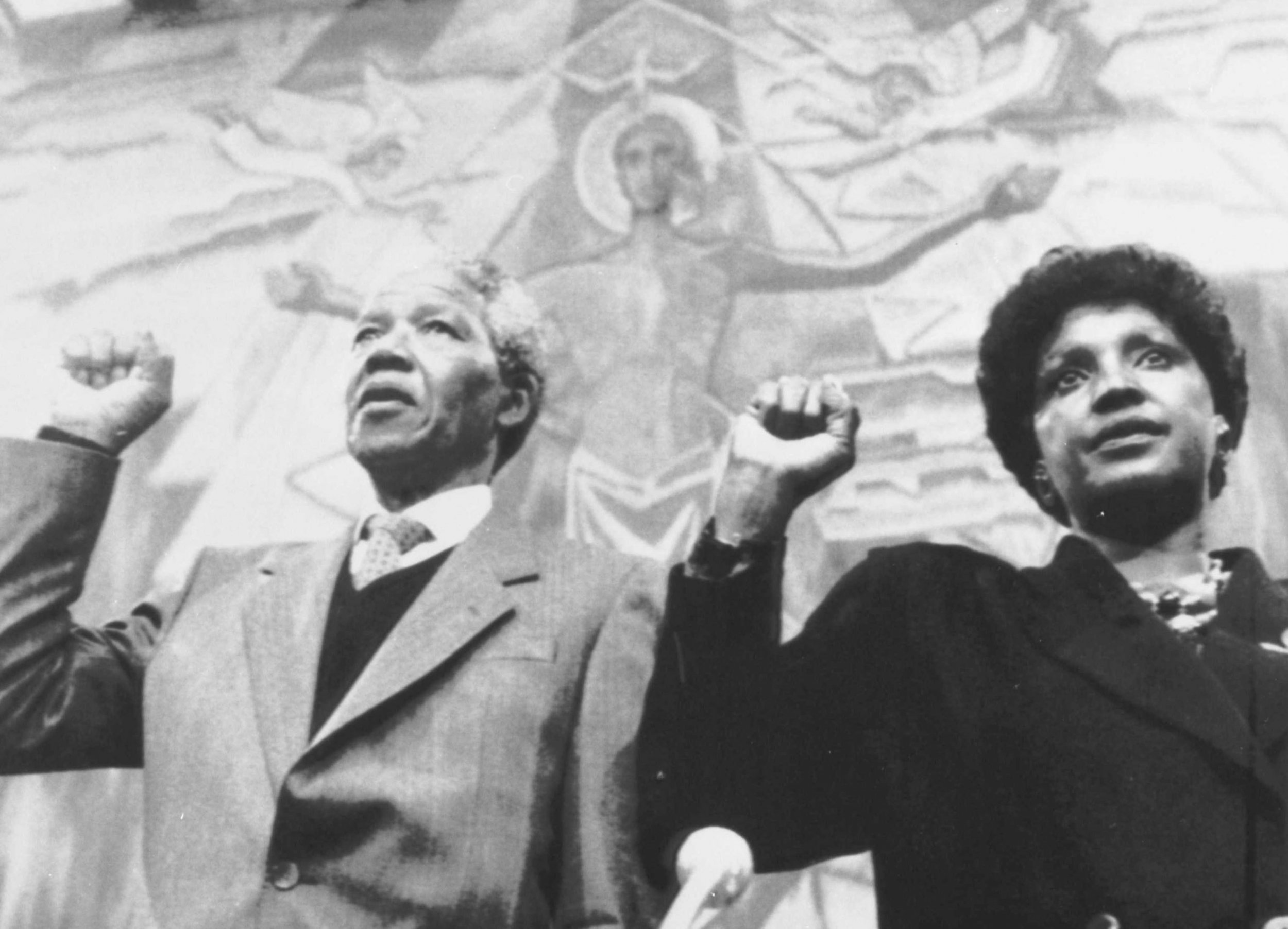

Newsweek published this story under the headline "He's Only Human, After All" on April 16, 1990. In light of the 55th anniversary of Nelson Mandela's arrest, Newsweek is republishing the story.

Inside prison walls, Nelson Mandela was a symbol and a hero. Outside, he has displayed some of the weaknesses that plague other politicians. "Let's face it, Mandela is human," says another black veteran of the prison on Robben Island. "Outside isn't like inside. Inside, you can't do wrong, you become a myth." Thrust into a world that has moved 27 years beyond the one he left, Mandela is relearning politics the hard way: by making mistakes.

He has often overestimated his own ability to bring about change. When he urged foreign governments to break diplomatic ties with South Africa and to stiffen sanctions, no one listened. When he asked Zulus fighting one another in Natal province to throw their weapons "into the sea," the violence continued. When he agreed to meet with Zulu leader Chief Mangosuthu Buthelezi, he had to renege under pressure from his own supporters. Last week, however, Mandela won a small victory that strengthened his credentials as a peacemaker.

In a meeting with President F. W. de Klerk, Mandela got enough concessions to put preliminary negotiations between the government and his African National Congress (ANC) back on track. The ANC had pulled out of the "talks about talks" as a protest against the largely unprovoked killings by police of at least 11 demonstrators in the township of Sebokeng four days earlier. Mandela's supporters said the cancellation was designed to push de Klerk into action against the police. "We must be able to convince our people that there is a distinction between de Klerk and conservative elements in the police and Army," said Peter Mokaba, 31, president of the South African Youth Congress, an umbrella organization for some 500,000 "young lions." In three hours of talks with de Klerk, Mandela won a promise that the Sebokeng shootings would be investigated. The two sides also decided that a steering committee would finalize arrangements for the new talks, to be held May 2 to May 4, about how to negotiate a political settlement.

Mandela's difficulties as a peacemaker were not limited to dealings with the government. One of his top priorities was to end black-on-black violence between Zulus in Natal. For more than three years, ANC supporters have been battling members of Buthelezi's conservative Inkatha movement. Nearly 3,000 people have been shot dead, burned alive, or hacked to death with machetes. Mandela couldn't get them to stop. "He invested too much in the authority of his own personality," says Mark Swilling of Johannesburg's Center for Policy Studies. "He assumed that if Nelson Mandela said throw your machetes into the sea, the machetes would go into the sea. That's not how politics works here."

Failing to discern the depth of distrust of Buthelezi among his own followers, Mandela set up a meeting and joint rally with the Inkatha leader. The meeting never came off. Inkatha war parties armed with spears and shotguns intensified their attacks. In 10 days of clashes beginning March 25, about 85 people were killed, most of them ANC supporters. Mandela's decision to meet Buthelezi went down very badly. "He thought it would stop the violence," said Sibusiso Peteres, an ANC supporter in Imbali, a hard-hit township. "But I think we know better."

New approach: For now, Mandela's greatest success has been to maintain the cohesion of the ANC's leadership -- which is scattered in South Africa, Tanzania, Zambia and Sweden, where the president, Oliver Tambo, is recovering from a stroke -- and to get the peace process started. "Do you think that if Mandela hadn't agreed to negotiations, anyone would be talking about negotiations right now? No way," says Youth Congress leader Mokaba. So far, no ANC hard-liner has publicly opposed Mandela's initiatives. Several have praised the new approach. And Mandela has made an effort to cultivate and consult younger activists.

Positions taken by Mandela that seem mistaken to many whites -- retaining the ANC's commitment to armed struggle and defending nationalization as future economic policy -- seem to be based largely on his need to maintain credibility among the more radical activists. Although Mandela has made mistakes, none has been critical yet. His supporters hope he'll solidify his position and get a better feel for his various constituencies. One quality that will serve him well is his patience. "This is the last mile toward liberation," says Mokaba, "and we all accept it will be the longest and hardest."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.