Leonardo da Vinci's Salvator Mundi , or Christ depicted as the "Savior of the World," recently sold for a record-breaking $450 million (below).

Over the past week, speculations have swirled about the identity of the new owner of the painting, which, despite lingering concerns about its authenticity and state of preservation, has been publicized as the last remaining work by the artist available on the market.

Some reports, citing US intelligence sources, have pointed to Saudi Crown Prince Muhammad ibn Salman as its owner, via his cousin Prince Badr, who served as an intermediary purchaser.

In response, the Saudi embassy in Washington, DC, has posted a note on its official web page to dispel such accounts, and the Abu Dhabi Department of Culture and Tourism has confirmed its acquisition of the painting.

Although many questions about the nature of the purchase and the identity of the buyer remain, one thing is clear: soon it will make its debut at the Louvre Abu Dhabi, where—much like Leonardo's Mona Lisa in the Musée du Louvre—it promises to attract international tourists and to generate revenue from admission fees and souvenirs.

American journalists have been perplexed by the Salvator Mundi 's purchase by a (purportedly) Saudi patron and by its journey to the United Arab Emirates, a Muslim-majority country.

Many have been quick to state, as we so often hear in the mainstream media, that " Islam prohibits any work of art representing a human being, and that the depiction of any of the prophets is especially forbidden."

Some writers and scholars even have noted that it is "weird" that this " distinctly non-Islamic Leonardo " might be purchased by a Saudi patron, as a portrait of Jesus should be considered a most graven image in Islam.

Yet to many Muslims across the Middle East, and to those familiar with Islamic history and art, it comes as no surprise that a Christian pictorial representation of Jesus would be preserved and displayed in an Islamic country.

Indeed, since the emergence of Islam during the 600s, positive narratives about icons, the making of devotional paintings, and the preservation of European printed images of Jesus Christ can be found across Arab, Persian, Turkish, and Indian lands.

These textual and visual materials disprove the notions that Muslims are inherently adverse to figural representation and that they might consider a depiction of Christ, like the Salvator Mundi, a graven image.

The story of images of Jesus Christ in Islam can be traced to the earliest Islamic texts, which describe the Prophet Muhammad's reconsecration of the Ka'ba in Mecca upon his return to the city after a period of exile.

Writing in the 8 th century, Muhammad's biographer Ibn Ishaq informs us that Muhammad smashed approximately 360 idols that represented the pagan gods of Arabia. At the very same time, however, he is said to have safeguarded an icon of the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ, possibly of Coptic or Byzantine manufacture, which was stored inside the Ka'ba until the building's eventual destruction in a fire.[1]

This detail indicates that Muhammad's act of iconoclasm did not seek to obliterate images ipso facto. Rather, he attempted to overthrow paganism and polytheism—via their associated objects and symbolic stand-ins—in order to establish a purely monotheistic world order, even as he reasserted the positive value of maintaining an image of Mary (a holy woman) and Jesus (an Abrahamic prophet) in Islam's holiest site.

Thus, if Crown Prince Muhammad ibn Salman is indeed the purchaser and/or owner of the Salvator Mundi , his acquisition need not be couched as the curious case of a Muslim leader coming into the pricey possession of a graven image. Quite to the contrary, it could be argued that he is following the prophetic example of preserving and displaying an icon of Christ.

Indeed, the recent purchase of Leonardo da Vinci's painting is not the first instance of a Muslim leader showing respect to, and ensuring the preservation of, a Christian figural representation of Jesus.

For example, when the Ottoman sultan Mehmed II, known as the "Conqueror," wrestled Constantinople from Byzantine hands in 1453, he headed directly to Hagia Sophia, the magnificent domed church built in 532–37 for Emperor Justinian I, where he described the church as heaven on earth and ordered the call to prayer sounded.

Upon the church's conversion to a mosque, he did not order the ninth-century apse mosaic of the Madonna and Child removed or covered (below). Instead, Ottoman chronicles tell us, Sultan Mehmed stood in awe, feeling that the eyes of the painted Christ child followed him as he moved (a sensation also reported by visitors to the Mona Lisa).

Unlike the other figural mosaics in the church-turned-mosque, this representation remained on view, perhaps because Ottoman rulers wished to conserve this image of Christ in emulation of the Prophet's own actions at the Ka'ba.[2]

At times, depictions of Jesus Christ could prompt iconoclastic acts, such as the removal or reconfiguration of mosaic stones or the overstriking of an item with Islamic inscriptions.

Nevertheless, during the medieval period, and most especially during the 13 th century, Muslim artisans produced a vast array of metalwork that includes Christian images. Among these objects, a large canteen made in the Mosul area, in modern-day northern Iraq, includes a central image of the Virgin Mary with Christ Child enthroned (below), as well as other scenes depicting the birth of Christ and his presentation at the Temple in Jerusalem (Luke 2:22–40).

Scholars have argued that this object might have been made for a Christian monastery or shrine in upper Mesopotamia, where it most likely contained water mixed with oil that burned over Christ's tomb in Jerusalem. This sacred liquid would have been sought by both Christians and Muslims living in the area.[3]

During the medieval period, images of Christ on these types of metalwares thus were available to members of both faith communities, for whom they fulfilled various devotional needs.

Jesus Christ, known as the Prophet 'Isa in the Arabic language, appears in the Qur'an and in other Islamic sources. Additionally, episodes from his life are illustrated in world histories as well as texts that belong to the "stories of prophets" genre.

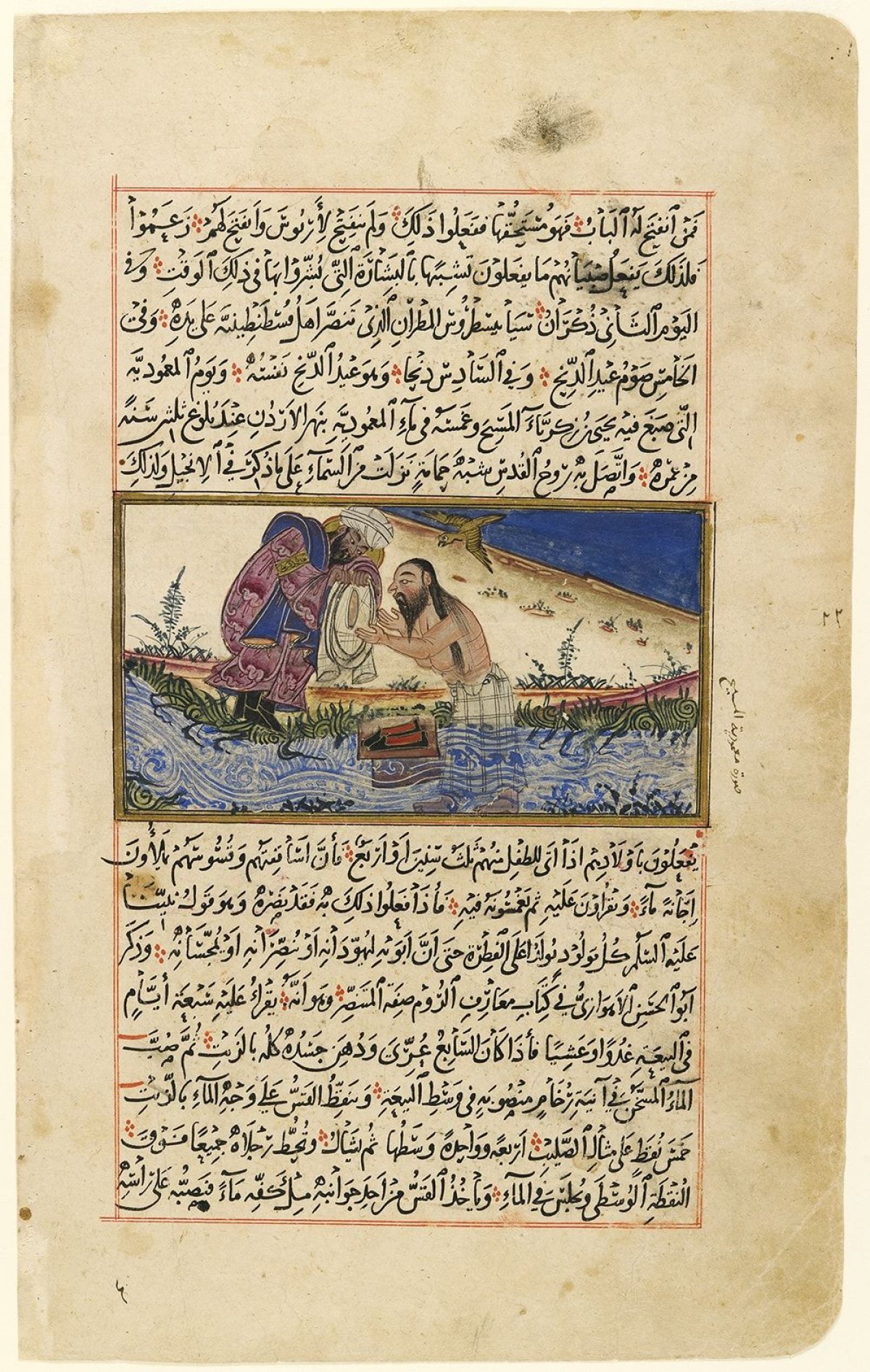

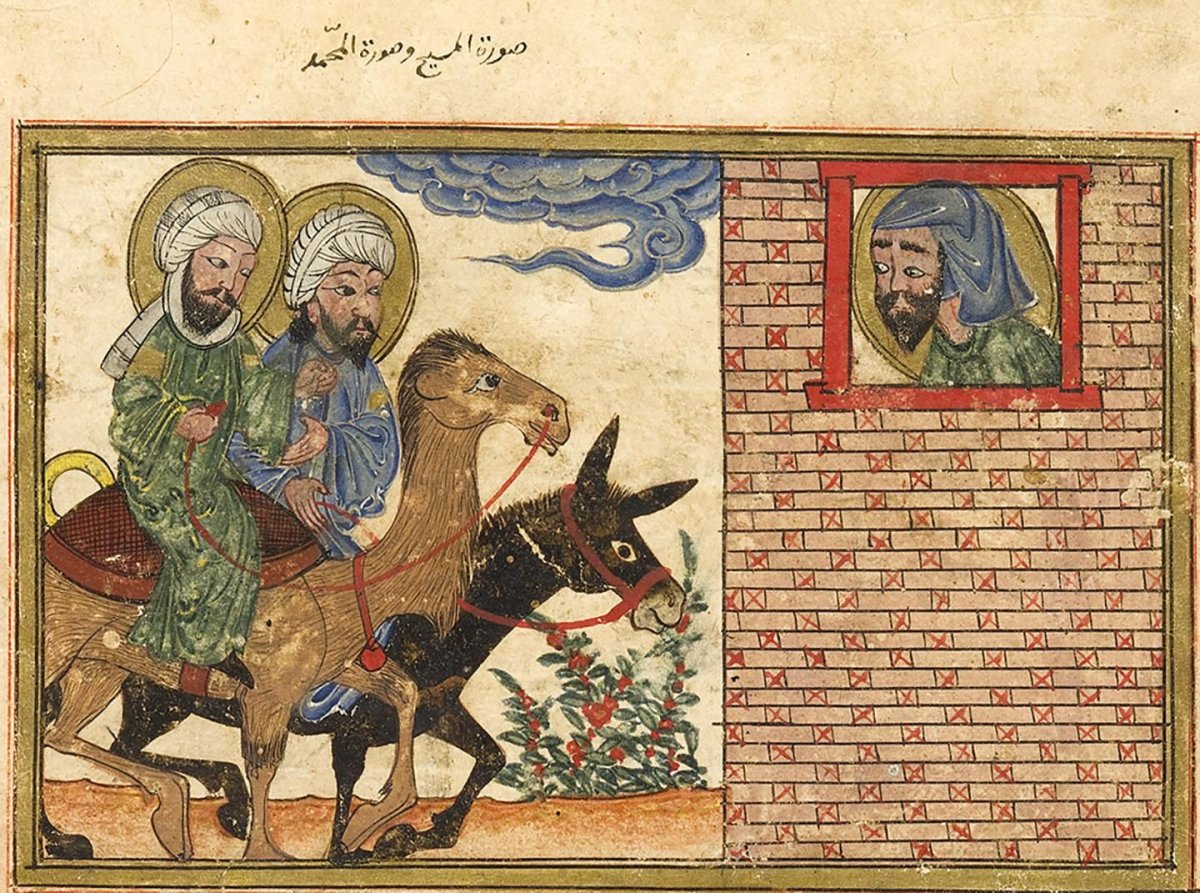

For example, the Muslim polymath and author al-Biruni (died 1048) writes about the Virgin Mary and Jesus Christ in his universal history entitled Chronology of Nations. Produced in Iran as an illustrated manuscript in 1307, it includes depictions of the Angel Gabriel's annunciation to Mary of Christ's birth, the baptism of Christ by John the Baptist (below), and Isaiah's apocalyptic vision of Jesus and Muhammad (far below).

These manuscript images serve to illustrate and promote the immaculate conception, the expiation of original sin, and the messianic return of Christ on the Day of Judgment—the latter a theme also depicted in Islamic paintings from the medieval period onward.

Images of Jesus Christ—made both in European quarters and in Islamic lands—became especially popular in India at the end of the sixteenth century, when Jesuit missionaries were present at the Mughal court.

These Christians brought with them the illustrated Royal Polyglot Bible and plenty of Christian engravings. Interested in the visual arts as well as interfaith dialogue, Mughal rulers ordered such items collected into lavishly illuminated albums of calligraphies, paintings, and prints.

For example, one 17th -century album includes dozens of images of the Virgin Mary and Christ, some of which are original European black-and-white prints, while others were painted in by Mughal artists or are creative adaptations of European originals.[4]

In the upper right corner of one page, a haloed Jesus Christ is shown with an open book proclaiming "Ego sum lux mundi" (I am the light of the world; John 8:12) (below). Below him, another inscription reads "Illumina d[omi]ne v[u]ltu[m] tuu[m] super nos" (May, O Lord, the light of thy countenance shine upon us; Psalm 66).

Here, a Mughal artist has copied a European original, carefully transcribing the Latin texts yet placing the image within a typically Mughal building constructed of red sandstone. This Christ as Lux Mundi proves an intriguing preview to Leonardo da Vinci's Christ as Salvator Mundi , whose own eastward peregrinations surely will inspire emulations as well.

Still today, images of Jesus Christ can be found across the Islamic world. This is especially the case in Iran, which boasts a vibrant public arts scene. A stroll through Tehran will take both resident and tourist alike past several images of Christ, from a large and rather ethereal mural serving as a decorative background to an exercise park to a small-scale sculpture punctuating the green space in Saint Mary's Park (below).

Both mural and sculpture were sponsored by Tehran's municipality, aim to pay tribute to the Christian communities of Iran, and, above all, prove possible thanks to the financial and logistical support of the Islamic Republic of Iran.

Not a "weird" one-off, the Salvator Mundi thus finds itself in excellent company as it joins an already lively corpus of European and Islamic images of Jesus Christ in the Islamic world, where it promises to stimulate further creative responses and cultural pilgrimage. The painting also challenges journalists, scholars, and the public at large to be much more nuanced and accurate when we speak about Islamic artistic traditions, lest we ourselves come to reclassify and lambast such images as "heathen idols" necessitating destruction.

Christiane Gruber is Associate Professor of Islamic Art, the History of Art Department at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

Notes

[1] Ibn Ishaq, The Life of Muhammad: A Translation of Ishaq's Sirat Rasul Allah, translated by Alfred Guillaume (Lahore: Pakistan Branch, Oxford University Press, 1955), 554.

[2] Henry Matthews, "From the Fifteenth Century to the Present Day," in Hagia Sophia, ed. Eugene Kleinbauer (London: Scala Publishers, 2004), 84, 88.

[3] Heather Ecker and Teresa Fitzherbert, " The Freer Canteen, Reconsidered," Ars Orientalis 42 (2012): 177–93.

[4] See Milo Cleveland Beach, "The Gulshan Album and its European Sources," Bulletin of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston 63, no. 332 (1965): 63–91; and, for a more recent analysis, see Yael Rice, " Lines of Perception: European Prints and the Mughal Kitabkhana," in Prints in Translation, 1450–1750: Image, Materiality, Space , ed. Suzanne Karr Schmidt and Edward H. Wouk (New York: Routledge, 2017), 202–23.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.