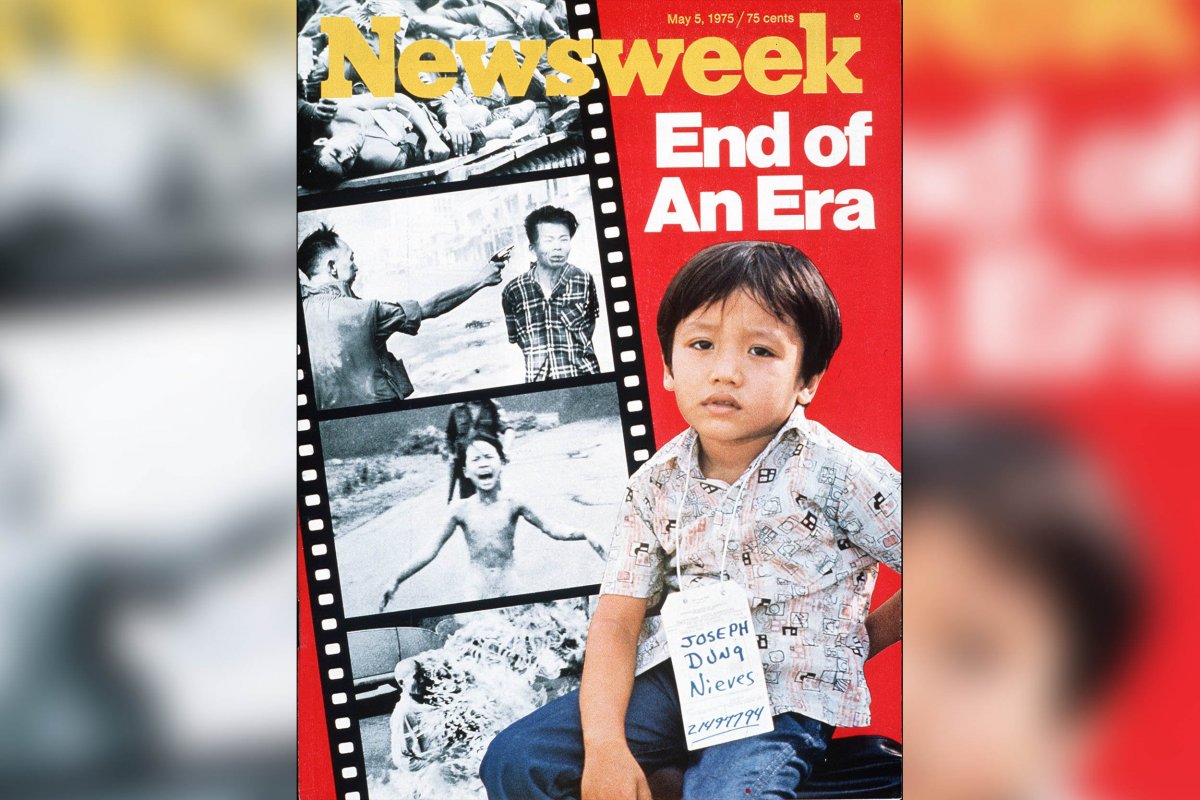

The end of the Vietnam War on April 30, 1975, was a much-anticipated and emotionally fraught event for the American public.

In our May 5, 1975, issue, Newsweek wrote about President Gerald Ford's April 23 speech at Tulane University in New Orleans, during which he announced the end of U.S. involvement in Vietnam. Editor Richard Steele explained the complexities of the conflict's end, with Americans in Saigon requiring evacuation, and the traumatic legacy of the divisive war that was still to be addressed.

The End of an Era

Back in another America, people used to dance in the streets when a president declared the end of a war. Last week, on a steamy night at Tulane University in New Orleans, Gerald Ford spoke the words that all of the United States had longed to hear: The war in Vietnam, the president said, "is finished as far as America is concerned." But it wasn't as simple as that. Whatever sense of relief the U.S. experienced at hearing Ford's unilateral declaration of peace was matched by a feeling of grief. There was still one final scene to be played out—the evacuation of the last Americans in Saigon—and that could yet turn ugly, and perhaps even bloody. Then, too, there was the anguished realization that it would be impossible for the U.S. to rescue all of the thousands of South Vietnamese who had staked their lives on America's commitment to their country. And there would always be the pain of knowing that while the war was finally over, a traumatic era was ending with a humiliating U.S. loss.

North Vietnam's armies stood massed at the gates of Saigon, able at the drop of a command to capture the capital city. South Vietnamese President Nguyen Van Thieu resigned with a venomous attack on the United States and a pledge "to stay close to you all in the coming task of national defense." Four days later, he fled to Taiwan. Into Thieu's office stepped his feeble and aging vice president, Tran Van Huong, but the Communists branded that exchange a "ridiculous puppet dance." Power passed Duong Van (Big) Minh, the one man acceptable to the Reds. In the face of the certain North Vietnamese victory, the Ford administration sought to mount a last-hour search for a negotiated end to the debacle. But just in case that didn't work, a task force of evacuation ships, fighter planes, helicopters and combat ready U.S. marines formed up off the shores of South Vietnam—ready to fight to save American lives in the last pullout from Indochina.

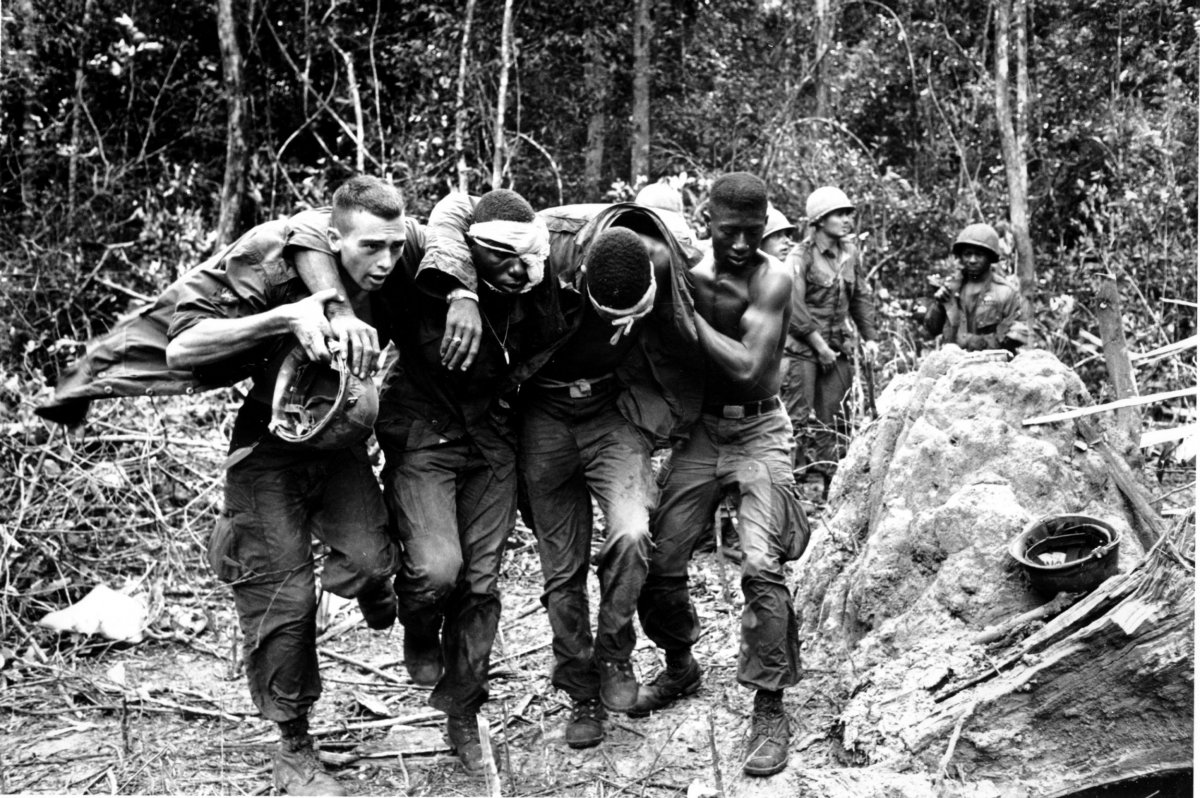

Every war scars nations as well as people. But only one conflict in American history—the Civil War—ever divided the United States more brutally than Vietnam or imprinted such an album of nightmarish images on the national psyche. Ford labored hard in his speech at Tulane to rekindle a sense of pride and confidence that would illuminate the post-Vietnam era. "These events, tragic as they are," he said, "portend neither the end of the world nor of America's leadership in the world." That was true enough but the Vietnam adventure diluted the confidence of America in its ability to influence events abroad—and its faith in itself to cope with problems at home.

For more than a decade, Vietnam convulsed every aspect of American life. The war drew the executive and legislative branches of the government into bitter conflict over the control of American foreign policy—a clash that ended with the Congress legislating stern limits on that once-sacrosanct presidential power. It undermined the American economy and touched off an inflationary spiral so severe that for years to come no politicians would dare to promise both guns and butter. While it produced no national heroes at arms—no Sergeant York, no Audie Murphy—it assembled a mixed bag of historical footnotes—men as disparate as Abbie Hoffman, William Calley and Daniel Ellsberg.

Perhaps the cruelest intrusion of Vietnam upon America was what it did to a generation of American youth. It sent thousands of men fleeing into self-imposed exile and turned their neighbors and their nation against them. It turned thousands of others into radicals—if only temporarily—and brought violent riots to city streets and college campuses. It claimed the lives of 55,000 American men.

An Air of Mystery

There was a lingering fear in Washington last week that, in the chaos of the final collapse of Saigon, even more American lives might be lost. The administration's goal was clearly a negotiated settlement, and while the White House hoped for an interim coalition it it knew it would have to settle for an immediate South Vietnamese surrender. American, French and Soviet officials created the impression that an earnest diplomatic campaign was under way, but if so, it was shrouded in mystery.

The president's right-hand man, Donald Rumsfeld, set off to attend a NATO meeting in Turkey, but the trip sparked speculation in Washington that Rumsfeld had borrowed Henry Kissinger's old secret agent's cloak and was engaged in a diplomatic mission on Vietnam as well. For his part, Kissinger referred in Congress to negotiating "efforts"—but refused to specify what they might be. Even the North Vietnamese flashed some encouraging signals, at one point passing the word through intermediaries that they had no desire to humiliate the U.S. But they refused to say whether—or what—they were willing to negotiate.

With 16 well-armed divisions encircling Saigon, the Communists clearly saw no need to compromise on their demands. They seemed determined to hold the city hostage and force South Vietnam's impotent government to surrender or face savage destruction within the capital. Pentagon analysts maintained that the battlefield lull was no humanitarian gesture to permit the U.S. a graceful exit from Saigon; rather, it was a tactical pause, aimed at triggering a panic in the city and ending all possible resistance to a Communist takeover.

No more than 1,100 Americans remained in Saigon by the weekend, but the administration also hoped to bring out as many as 130,000 South Vietnamese. Top priority went to American dependents, but the lists also included 75,000 "fireside relatives"—in-laws and children of Americans—and 50,000 "high risk" Vietnamese—former U.S. government employees and some government officials and intellectuals whose lives were believed to be at risk. All week long, giant jets lumbered away from Saigon carrying out about 5,000 persons a day. Some went to tent cities on the Pacific islands of Guam and Wake, others to military bases in the U.S. itself, where the vast majority was expected to be resettled. Arrival in America did not mean that the refugees' problems were over. U.S. officials acknowledged that an era of difficult assimilation almost certainly lay ahead for the newcomers.

The airlift of Americans and South Vietnamese met no interference from the Communists, but there was continuing concern in the U.S. Congress that such luck might not last. Congressional leaders called on the administration again last week to speed up the evacuation of Americans. The Senate, by a vote of 46 to 17, gave the president full power to send in U.S. forces to aid the departure of Americans and their dependents. The measure also allotted $327 million to pay for the operation and for humanitarian aid to South Vietnam, but it placed stringent limits on Ford's authority to deploy U.S. troops. The bill specifically stipulated that only those forces "essential" to the pullout of Americans and their dependents could be deployed and that none could be used in unrelated evacuations of South Vietnamese.

The Saddest Chapter in a Century

Within the Ford administration as well, there was a growing desire to get the Americans out. Defense Secretary James Schlesinger urged that the U.S presence in Saigon be slashed drastically—to no more than about 200 officials—and that only in case of a dire emergency should American troops be sent in to aid the evacuation of dependents from South Vietnam. Secretary Kissinger finally confided to the House Appropriations Committee that the administration's pitch was in fact designed to achieve an orderly withdrawal of U.S. citizens. Ford in effect acknowledged the same thing with his declaration that America's war in Vietnam was finished. "The time has come," the president then said, "to look forward to an agenda for the future, to unify, to binding up the nation's wounds and to restoring it to health and optimistic self-confidence."

It will not be easy. The war has been the saddest chapter in the past century of American history, and it will take years for the U.S. to come to grips with what it did to Vietnam—and what Vietnam did to America. The faith of Americans in their leadership was practically destroyed, and many were left convinced that they had been both seduced and deceived by their government. The war added a cynical new vocabulary to the American idiom—"light at the end of the tunnel," "protective reaction," "smart bombs," "peace with honor"—and it eroded the legitimacy of authority throughout the country.

"The times they are a-changing," wailed Bob Dylan, the nasal troubadour of his generation. Vietnam brought incalculable changes to American life. The society had already been shaken by the revolt of the blacks; Vietnam accelerated the transformation. Out of the protests and mass movements grew a lifestyle that came to be called the "counterculture." Some of the manifestations were as evanescent as Day-Glo paint, but others seeped into the soul of the nation's young. Protest over the war led to a whole new politics that ultimately involved the rights of women, homosexuals and every other alienated sector of society.

A Bitter Remembrance

Vietnam also warped the relationship between America and its allies. The world has a different view of America because of Vietnam: some nations blame the United States for what it did in Vietnam, others for what it didn't do, still others for the manner in which it finally got out. The war strained the country's ties with some of its traditional partners in Western Europe and antagonized those nations that compose the Third World. At the same time, the war made the United States suspicious of that outside world, and while America will surely never revert to its old brand of isolationism, the shaken nation has already shrunk from some global responsibilities out of fear of "another Vietnam." Such is the legacy of Vietnam: a bitter remembrance of things past that is sure to haunt the future.

Richard Steele with Mel Elfin, Hal Bruno and Thomas M. DeFrank in Washington.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.