Nobody likes to think his or her iPhone was made from minerals derived from a country where warlords and mass rapists profit from the mines. So a year ago, Apple made a bold claim: It had audited smelters in its supply chain and none of them used tantalum from war-torn regions in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC).

While Apple acknowledged that it could not make the same claim for gold, tin and tungsten—three other important commodities essential to modern electronics but mined in war zones—the announcement about tantalum was an important step for human rights advocates who have long called for more transparency from international companies.

But how can Apple be so sure?

Experts note the widespread smuggling of ore across porous borders in areas racked by conflict, with scarce paper trails for ore mined by villagers in small artisanal mines in countries where warlords control exports. Moreover, audit procedures at smelters in China and Russia are opaque and vulnerable to corruption. "We're concerned that the audit procedures are not as transparent as they should be," says Sasha Lezhnev, who oversees DRC conflict minerals issues at the Enough Project, part of the Center for American Progress think tank.

The disclosure by Apple, which just reported the largest quarterly profit of any company in corporate history, was unusual in that it went beyond a new regulation passed by the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) in 2012 under the 2010 Dodd-Frank financial regulation act. That new rule requires U.S. publicly traded companies to audit their supply chains and disclose any use of conflict minerals—but not the names of smelters, as Apple did.

Apple's data came through the Conflict-Free Sourcing Initiative (CFSI), a self-policing, voluntary group created in 2009 to vet smelters for the sources of potential conflict minerals. Backed by Apple, Intel, Microsoft, Hewlett-Packard, General Electric and other major consumers of such ores, the audit program has seen various tweaks to its procedures as it clears smelters in recent years.

Nearly all computers, cellphones and other high-tech gadgets use tantalum, a pearly, blue-gray mineral found in Brazil and Australia but also in Rwanda and the DRC, which has endured what the International Rescue Committee calls the bloodiest conflict since World War II. More than 5 million people have been killed there since 1998, rape has been used as a weapon of war, and slave labor and conscription of child soldiers are common.

Named for a Greek mythological figure doomed to spend eternity in shallow water, with fruit hanging forever out of his reach, tantalum is traded on a market that is one of the world's most secretive. Tantalite, the ore bearing tantalum, is not traded on commodities exchanges but instead bought and sold through shadowy networks of dealers, so its origins are easily disguised. Refined into coltan at smelters in countries such as China, Kazakhstan and the United States, the mineral is sold to manufacturers that make capacitors, high-tech devices that hold electrical charges and are essential to everything from iPads to airplanes.

In February 2014, Apple for the first time named all the smelters in its supply chain that handle the four conflict minerals (tantalum, gold, tin and tungsten). They were in countries including China, Brazil, the U.S., Japan, Germany, India, Austria, Estonia, Russia and Kazakhstan. It said CFSI audits showed the smelters did not use any tantalum mined in war-torn regions in the DRC. This month, Apple is expected to disclose fresh details on CFSI audits of its smelters.

Last November, Apple said that of the 219 smelters it uses globally to process gold, tin, tungsten and tantalum, 106 were fully compliant, 55 were in the process of being audited, and 58 fell into the sketchy we-don't-know category. The figures show progress—more smelters refining clean metal or undergoing audits to ensure they do—compared with just six months earlier, when Apple said that of the 186 smelters it used for the four metals, just 59 were compliant, 23 were undergoing audits, and 104 had not participated in audits.

"CFSI has successfully lured some metal processors into the gaze of public scrutiny," says Sophia Pickles, who oversees Congolese conflict minerals issues at Global Witness, a global-development advocacy group. But, she adds, "the scheme risks being seen as a green-washing, 'tick-the-box' exercise." She was referring to various steps in CFSI's lengthy audit procedures that allow auditors to scrutinize smelters to check off various areas of compliance—such as spot checks on paperwork, and interviewing smelter employees. Such procedures fall short of global standards set by the Organisation for Cooperation and Economic Development because they do not require smelters to publicly report on risks uncovered or any corrective steps.

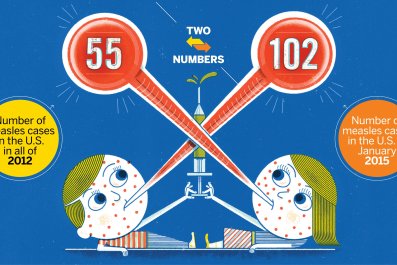

Some 6,000 companies, in industries ranging from telecommunications to health care, are expected to spend an initial $3 billion to $4 billion to comply with the new SEC rule, and up to $609 million annually after that, according to SEC estimates. So when barely 1,300 companies filed initial disclosures last summer, there was some concern and disappointment. With just 23 percent of reporting companies declaring that all of their products were DRC conflict-free, according to Audit Analytics, expectations are higher for this year's disclosures.

Michael Littenberg, a lawyer at Schulte Roth & Zabel who focuses on legal issues surrounding conflict minerals, says that "right now, the reputational risk is higher" due to disclosures by many tech firms last year that raised expectations of more and better to come. "Big consumer brands" like Apple "are the low-hanging fruit for nonprofits and investor advocates, and they're increasingly focused on this issue."

Scrutiny of conflict minerals has increased over the past decade, but the trade remains hard to track. In December 2014, Rwanda disclosed that in 2013 it dramatically boosted tantalum exports to become the world's largest exporter, shipping out to foreign smelters, mostly in China, some 2,460 tons, 28 percent of the global total of around 8,800 tons. That is more than double 2012's exports, despite the fact that Rwanda has consistently produced around 1,500 tons annually, according to United States Geological Survey data.

The spike deepened suspicions that ore was being smuggled across the border from conflict areas in the DRC. In April 2013, more than two years after the CFSI began auditing smelters, Global Witness reported that "much of the tin, tantalum and tungsten produced in North and South Kivu" in the DRC "benefits rebels and members of the state army. The minerals are smuggled out of Congo into Rwanda and Burundi for export. Tin and tantalum smuggled into Rwanda is laundered through the country's domestic tagging system and exported as 'clean' Rwandan material."

The CFSI audits of smelters rely on a screening initiative created by the International Tin Research Institute (ITRI) that provides data on the source of the minerals. Although it is run by the global tin industry, ITRI tracks all four conflict minerals, screening mines and allowing local producers to "bag and tag" conflict-free material. But ITRI audits are not made public, and none of the screening initiatives, including the CFSI, have undergone third-party reviews.

"When you think about the context of these mines being primarily artisanal, very informal, there is no paperwork, so what evidence do any of the audits have to rely on?" asks Lawrence Heim, director at Elm Sustainability Partners, a conflict minerals consulting firm in Marietta, Georgia. "At the end of the day, we don't really know what the reality is."

William Quam, an industry consultant in Vienna who in recent years managed 3,800 miners and staff across six tantalum mines in Rwanda and who has also worked in the DRC's North Kivu region, says patchy rollout of the screening initiatives was fueling smuggling—something flagged in a U.N. Group of Experts report last August. "Owning the bag and tag process is more profitable than smelting," Quam tells Newsweek.

Asked about its audit procedures and how it can be sure the tantalum it uses is conflict-free, Apple declined to provide an official for an interview or to answer on-the-record questions sent by email.

Rob Lederer is executive director of the Electronic Industry Citizenship Coalition, one of the industry groups that developed the CFSI. He says: "While we cannot certify specific sales or shipments as conflict-free, we do provide assurance to companies that their smelters have procedures in place to source responsibly."

In June 2010, Apple co-founder Steve Jobs admitted the depth of the problem in a widely disseminated email sent to a reporter at Wired magazine: "Until someone invents a way to chemically trace minerals from the source mine, it's a very difficult problem."

Other tech companies have complied with the SEC regulation by admitting that they just don't know. Dell says on its website that "the mining of these minerals takes place long before a final product is assembled, making it difficult, if not impossible, to trace the minerals' origins. In addition, many of the minerals are smelted together with recycled metals, and at that point, it is virtually impossible to trace the minerals to their source." Taser International said it could not determine whether conflict minerals used in almost all of its products came from DRC conflict areas.

The SEC rule, unusual in that it puts the agency in a humanitarian watchdog role, requires only transparency and that companies conduct a "reasonable country of origin inquiry." It does not require companies to do anything about their suppliers, as long as they are open with investors and the public about them.

Even parts of that requirement are being challenged. Last April, a Washington, D.C., federal appeals court struck down the SEC rule's requirement that some reporting companies might have to disclose their products as not found to be DRC conflict-free. The ruling came in a lawsuit brought against the SEC in May 2013 by the National Association of Manufacturers, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the Business Roundtable, all powerful trade groups. They argue that the disclosure requirement violates the First Amendment right to free speech by forcing some companies to publicly wear a scarlet letter and to make a "forced confession that a company has blood on its hands," court papers say.

However, the outlook remains uncertain after an appeals court decision last November to rehear the issue. The label "conflict free," Raymond Randolph, the judge overseeing the case, observed in court papers, "is a metaphor that conveys moral responsibility for the Congo war."