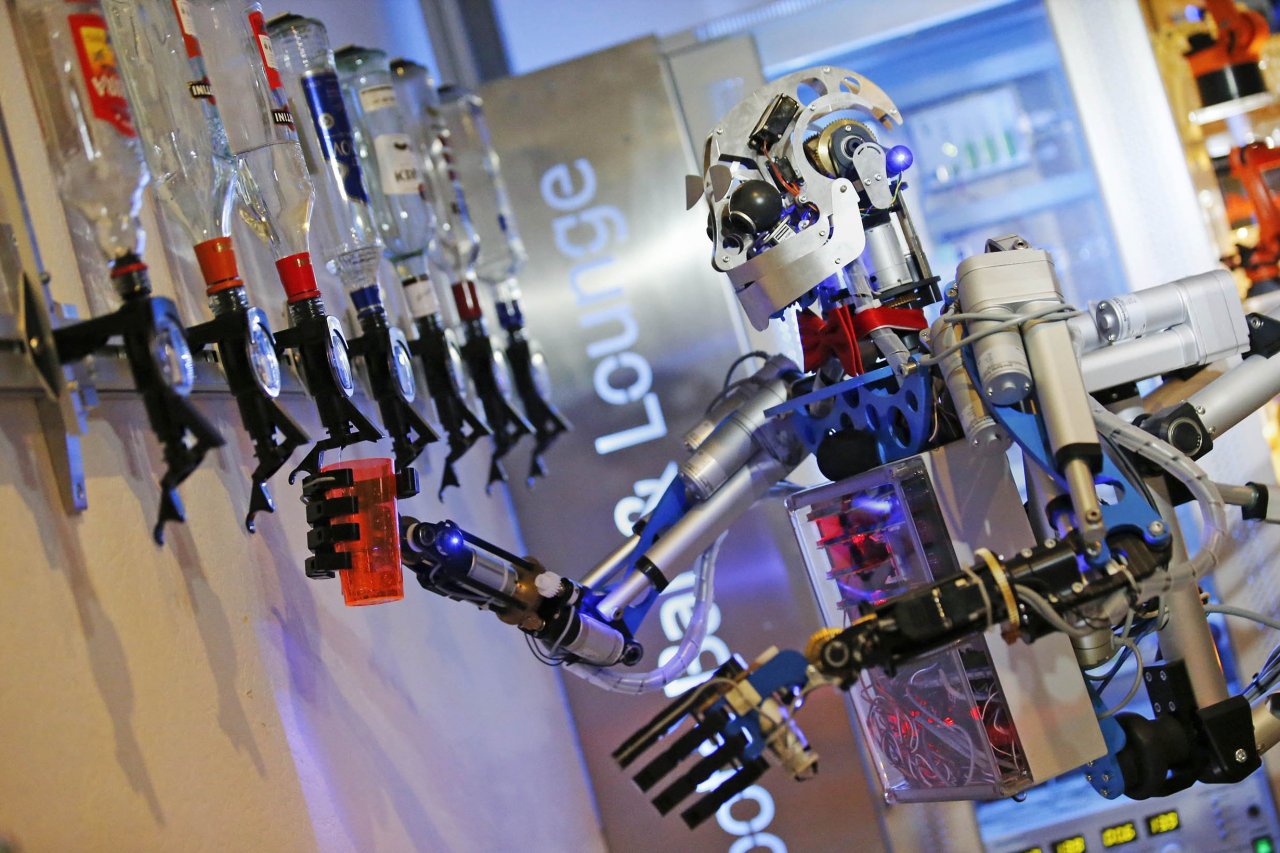

In 2011, Terry Gou, the chairman of Foxconn, the largest maker of computer components on the planet, stood up at an employee party and announced that he would replace the workers who spray, weld and assemble products for Apple, Sony and Nokia with 1 million robots in three years. Gou wanted to cut rising labor expenses after scandals about onerous working conditions and worker suicides had forced him to raise wages. Though Foxconn is behind schedule with its plan, the company has already added thousands of robots to its workforce.

Other companies—including restaurant chain Panera, gas and electric utility giant PG&E and many others—are making similar moves. If trends hold, smart machines—computers and robots equipped with artificial intelligence—will deplete the professional job market in the next decade as ruthlessly as automation and robots did the assembly lines in the 1980s.

Most forecasters agree that the mid-level jobs such as factory and clerical work are most at-risk. Unfortunately, these make up a huge portion of today's available careers. A 2013 study on the susceptibility of jobs to computerization came to a devastating conclusion: "Around 47 percent of total U.S. employment is in the high-risk category... jobs we expect could be automated relatively soon, perhaps over the next decade or two."

Jobs in transportation and logistics, says Carl Benedikt Frey, of the Oxford Martin School's Programme on the Impacts of Future Technology, could soon go away permanently. In part, this will be due to the rise of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), better known as drones. UAVs resembling mini-helicopters powered by batteries and employing GPS technology, sonar sensors, cameras, memory banks and communication could be dotting the sky within a decade. Last year, the U.S. National Transportation Safety Board overruled a ban on drones by the Federal Aviation Administration, which will have new rules for their operation by December. In the meanwhile, many companies are already investing in UAV technology, including Amazon, Aeryon Labs, the startup Skycatch and, through its acquisition of Titan Aerospace, Google. Once drones are deployed, they'll almost certainly have an impact on jobs: Imagine taking all of Amazon's packages out of mail trucks and delivery pouches and putting them into the air.

Because they have to follow the rules of the road (or the sky), jobs in transportation and logistics and are particularly vulnerable to the smart machine invasion, says Richard B. Freeman, co-director of the Labor and Work Life Forum at the Harvard Law School and director of the Labor Studies Program at the National Bureau of Economic Research. So are office support jobs. "They follow rules, which means they can be described by computer program," Freeman says. Careers in the service occupations, where most U.S. job growth has occurred over the past decades, are "highly susceptible to computerization." Freeman points to examples like ATMs and ticketing kiosks, where robots have already claimed many service jobs.

But smart machines can do more than just follow rules. Using big data and sophisticated analytics, they can offer up judgments as well. That's why Freeman believes that when it comes to being taken over by smart machines, "doctors, lawyers and accountants are next in line."

For example, smart machines can do many aspects of a radiologist's job, like reading and analyzing patterns of body scans. Oncologists at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Center in New York use IBM's Watson computer to not only diagnose cancer, but to develop individual patient treatment plans as well. Watson puts each patient's symptoms, medical, family and genetic history into the context of the available big data—more than 600,000 medical reports; 1.5 million patient records and clinical trials; and 2 million pages of medical journal text.

At large law firms, Symantec's Clearwell system scans big data of its own, combing through thousands of legal briefs and precedents for pretrial research. The most tireless law clerk in the land can't do what it does: analyze more than half a million documents in two days. And smart machines should soon be able to perform some of the easier lawyerly tasks, like crafting a boilerplate will or a simple divorce agreement.

Machine learning, which allows software to reprogram itself as it receives vast quantities of new data, is poised to take over the jobs of "even the smartest engineers," according to a 2014 report on smart machines published by the informational technology research firm Gartner. These smart machines look like they can handle engineering jobs in fields ranging from weather prediction to utilities management: The Greater Cincinnati Water Works and Metropolitan Sewer Department employ GE's machine learning platform to speed up its response to storms and overflow conditions.

A machine's absence of human needs, such as wages, sleep and food, is a clear advantage over their flesh-and-blood workers. A less obvious asset is a smart machine's lack of susceptibility to emotional weaknesses. Because smart machines are without bias, some economists envision them taking on, for example, the role of courtroom judges. One recent study showed that judges hand down more lenient sentences after lunch than before—something no machine would do.

Even those jobs the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics estimates will grow the most in the next decade are under attack. Take job opportunities for translators and interpreters, which the BLS estimates will grow at a higher rate—46 percent—than almost any profession from 2012 to 2022, and well above the 10.8 percent average expected growth rate of all occupations. "Though translation software have made the work of translators more efficient, these jobs cannot be entirely automated," the BLS reports. "Computers cannot yet produce work comparable to the work that human translators do in most cases."

Or can they? The more data today's translators log, the better tomorrow's smart machines become. For example, data from United Nations documents, which are translated by humans into six languages, are used by Google's free translation software to monitor and improve the performance of different machine translation algorithms. Those humans may be translating themselves out of a job.

It's not clear whether the jobs lost to smart machines will be made up for by the jobs created by the need to create, program, monitor and service those machines. "There's a huge amount of disagreement over whether in the new digital industrial economy, more jobs are created or more jobs are destroyed," says Kenneth F. Brant, research director at Gartner. "No one has a clear winning argument."

The computer revolution actually created a lot of job opportunities; Dell, for example, employed about 112,000 workers in 2013. But unlike those early computers, the latest machines are becoming smart enough to reprogram—even fix—themselves as needed. Smart machines are capable of predictive maintenance: able to anticipate when equipment, such as gas and water meters, needs to be serviced. Smart machines will even be able to operate, maintain and fix other machines, such as the robots used in manufacturing.

On the other hand, those jobs held by the humans who originally program the smart machines are probably safe. "Software engineers will never become outdated, because what they do involves so much creativity and originality," Frey says. Though algorithms such as those Google uses can dig deep into thousands of pages of information to find patterns, coming up with those algorithms in the first place is "very much a human element," he says. That also the reason why jobs held by people in the creative fields such as journalism, comedy and drama will remain untouched by smart machines, according to Werner Eichhorst, director of Labor Policy Europe for the Institute for the Study of Labor.

The professions now growing the most dramatically are those requiring the most mundane, low-tech and old-fashioned skill sets. These include occupations like personal care aides, who help the infirm get dressed and eat—and whose primary skill is compassion—and bricklayers, whose primary competence is a steady hand. In fact, most of the top 31 careers expected to have the most growth between 2012 and 2022 don't require a college education. So until smart machines acquire a human being's level of benevolence and dexterity, those jobs are safe.

And there may also be some untold potential with smart machines. They will create new jobs in the area of design, research and development, maintenance and supervision, Eichhorst believes. There will also have to be somebody to train new smart machine owners and users. Unlike many political scientists, Eichhorst also envisions smart machines and digitalization giving rise to new jobs in social services, health care, research and education.

If the future does hold less job opportunities than today, it may also come with this additional bittersweet outcome: greater productivity resulting from smart machines could lead to cheaper products, with the savings passed onto the consumer. For those left unemployed, such savings could be a godsend.

December 9, 2014: This article incorrectly stated that PG&E is a communications company. PG&E is a gas and electric utility provider.