It's difficult for any lawyer to represent someone prone to impulsive decisions, self-incriminating statements and potentially corrupt entanglements. But when that someone is the president, your legal advice exponentially takes on more scrutiny and weight.

Which is why Don McGahn, the White House counsel, has one of the hardest jobs in Washington. An election law expert, McGahn, 48, has faced plenty of heat for his involvement in almost every controversy with the Trump administration. He was the initial interlocutor with acting Attorney General Sally Yates when she reached out to warn about then–National Security Adviser Michael Flynn's potentially compromising conversations with the Russian ambassador. He was the one trying to clean up the mess from President Donald Trump's first travel ban. And he was part of a small circle of advisers present when Trump decided to fire FBI Director James Comey, who was investigating allegations of collusion between the president's campaign and Russia during the 2016 election.

Now, as four congressional committees and a special counsel continue to probe the White House, he's defending Trump as the president tries to fend off challenges to his executive authority and an investigation into possible obstruction of justice.

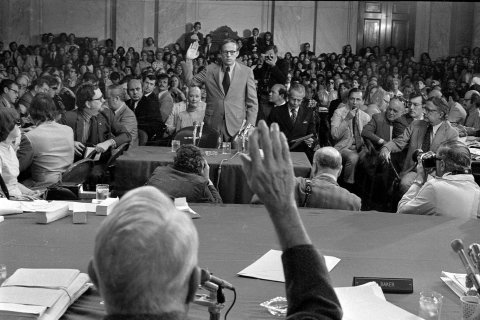

The challenge for McGahn: He's Trump's lead legal adviser, but he also serves the presidency as an institution. No one knows how tricky that is better than John Dean, President Richard Nixon's young counsel during Watergate. Dean initially helped cover up the Watergate break-in before becoming the star witness who ultimately brought down the president.

"The real issue when I was there was who is my client," recalls Dean, now 78. "Nixon thought he was the client." But the client is actually the office of the president, which includes not just the man elected to the role but also the executive role itself, not to mention the staff serving him.

Such a distinction is clear in theory but not always easy to discern in practice. From the Iran-Contra affair to Whitewater to the National Security Agency's domestic spying program, the president's legal adviser has often found himself embroiled in a war between political priorities and legal protocols. And the pattern that's emerged is pretty clear: When the White House allows politics to swamp constitutional concerns, the result is inevitably scandal.

Dean, who served four months in prison for his role in Watergate, warns that the president and his administration aren't the only ones imperiled by the Trump-Russia probes. Since he's not Trump's private attorney, McGahn could be forced to comply with a grand jury subpoena, something Bill Clinton's White House counsel's office faced during Whitewater. There is also some ambiguity about whether McGahn could be legally obligated to report wrongdoing by Trump, Dean points out.

"This is gray stuff," he says. And it could ultimately force McGahn into the same choice Dean faced 44 years ago.

There aren't a lot of formal parameters to guide the White House counsel. McGahn's office is an ad hoc creation of President Franklin D. Roosevelt, who devised the post for his longtime political adviser and speechwriter, Sam Rosenman, who also happened to be a judge. Over the next few decades, Roosevelt's successors hired a staffer alternatively called a special counsel or counsel to advise them, although not all were lawyers, and their advice was often more political than anything else.

It wasn't until Dean and Watergate that the job took on a more official and legal cast. As Dean recalls, his goal was to create "a little law firm" within the executive branch. He and his cohorts focused on many of the things his successors have been responsible for since—vetting appointees and mitigating conflicts of interest, helping select and vet judicial nominees and protecting the powers of the president. But by his third year on the job, Dean had been sucked into the undertow of scandal that eventually drowned the Nixon administration.

Since then, legal organizations have tried to set some ethical guidelines for the role and others like it. The American Bar Association rewrote the code of ethics it applies to attorneys, including those for lawyers representing a corporation or an entity like the White House. The code requires such lawyers to report potential lawbreaking to "a higher authority in the organization." Failure to do so could mean losing their law license.

But in the federal government, who is a higher authority than the president? Dean argues that if Trump is the one breaking the law by, say, attempting to obstruct justice, McGahn could report it to Congress or the Justice Department's special counsel, Robert Mueller. But other legal analysts say the code doesn't adequately address the unique issues of a government counsel's role, which leaves plenty of wiggle room for McGahn.

Either way, the evolving ethics haven't insulated the counsel's office from the intense political pressure that comes with the job. "I really was straddling law and politics," recalls Jack Quinn, a lawyer and lobbyist who served as Clinton's White House counsel between 1995 and 1997, as the Whitewater investigation ramped up. And it's telling that even as critics have slammed McGahn for failing to steer Trump away from legal pitfalls in his early months in office, his predecessors have been more cautious about passing judgment.

A counsel's legal advice is meant to be kept private, so it's hard to know exactly what McGahn has been recommending to Trump—and whether the president has been listening. The fact that McGahn was in the room when the president made the decision to fire Comey isn't "necessarily problematic," says Quinn. "Far better that he is in the loop than that these officials are not seeking legal advice."

The White House did cause a stir when spokesman Sean Spicer defended the president's delayed decision to fire his national security adviser by telling reporters the counsel's office had determined Flynn's conversations with the Russian ambassador did not amount to "a legal issue." But Dean observes, "You don't know if that's McGahn or Spicer going out and being told to say this." And as Barack Obama's White House counsel Bob Bauer wrote on the blog Lawfare earlier this year, it's difficult to grade a counsel's performance "in the absence of all the facts."

The Department of Justice's decision to launch a special counsel investigation into the Trump White House and its ties to Russia both simplifies and complicates McGahn's job. On the one hand, it prompted the president to retain a personal lawyer, Marc Kasowitz, who is not at risk of being subpoenaed the way McGahn and his staff are. That allows the White House counsel's office to return more of its focus to routine legal matters. As the Watergate investigation picked up, Dean was able to separate himself entirely from White House Watergate discussions (until Nixon fired him for talking to prosecutors).

"For eight months, I never talked to Nixon about Watergate," he recalls. "I had no idea what he knew. No one told me what they were telling him, which was awkward."

But it's hard to see how Trump's counsel will get to duck the Russia brief entirely. Congressional investigators' demands for access to White House staffers and their records have already prompted plenty of wrangling over the separation of powers and what the executive branch can legally withhold. During the Whitewater investigation, Quinn worked closely with Clinton's personal lawyers. Overlap is inevitable, he says, given that both attorneys are representing the same man.

Kasowitz has it easier than McGahn, as his legal responsibilities are much more straightforward, although he's caused some consternation by crossing onto McGahn's turf. Not only has Kasowitz invoked executive privilege in his defense of Trump, but The New York Times reported he was advising White House staff, prompting one watchdog group to file a complaint with the District of Columbia Bar Association.

As the headaches multiply, one wonders: Does McGahn, like Dean, have a breaking point? Trump is reportedly testing McGahn's limits with some of his ill-advised comments on social media. Senator Lindsey Graham got to the nut of the issue during a June 7 Fox News interview. "You need to listen to your lawyers, Mr. President," the South Carolina Republican said. "Every time you tweet, it makes it harder on all of us who are trying to help you."

Or, as Quinn observed, reflecting back on his own time in the crucible of a White House investigation, "Thank God we didn't have Twitter."