It's hard to upstage a figure as sainted as Eleanor Roosevelt, but author Amy Bloom has found a voice if not as saintly then certainly as memorable: Eleanor's onetime lover and lifelong friend, the tough-minded journalist Lorena Hickok. Their romantic relationship, actively erased by the press in their lifetime, remained in the shadows until Susan Quinn's 2016 dual biography, Eleanor and Hick: The Love Affair That Shaped a First Lady.

Historical fiction is a favorite of Bloom's, as are explorations of sexuality and gender, and Hickok had the sort of picaresque life the author favors—like the 1920s adventuress fleeing the pogroms of Russia in 2007's Away or the half-sisters of 2014's Lucky Us, in search of fame and fortune in 1940s Hollywood. White Houses is historical in a different way; there's a real timeline and reported facts. But Hickok's life story has enough gaps that Bloom could play around. What's undisputed is her desperate girlhood in South Dakota and a career as a reporter for the Associated Press. By 1932, Hickok was the most famous reporter in America.

Hick, as many called her, first interviewed Eleanor for the AP in 1928. In the next few years, their relationship deepened to the point that she could no longer objectively cover the Roosevelts. When FDR was inaugurated in 1933, Hick got a job investigating his New Deal initiative—and a bedroom adjoining the first lady's in the White House.

Researching Lucky Us piqued Bloom's interest in the Roosevelts. "If you're looking in the '30s and '40s," says Bloom, "you can't escape them." That took her to the Roosevelt library and Eleanor's 18 boxes of correspondence with Hick—3,000 letters in all. "Somebody said to me, 'Why did you write a novel as opposed to a history?'" says Bloom. "Because I'm a novelist not a historian! It's like when people would say to Willie Sutton, 'Why do you rob banks?' It's because that's where the money is."

Newsweek spoke to Bloom about White Houses, now being developed into a TV series with Emmy-winning director Jane Anderson (Olive Kitteridge). "I love how Jane describes it," says Bloom. "It's the ragtag American version of The Crown."

Were you always an Eleanor Roosevelt fan?

In the vaguest way. My parents were Democrats and Jews from New York, and so Eleanor Roosevelt was in the family stream, just like unions were in the family stream. But I must have skipped most of American history in high school because I knew nothing about anything, which is amazing. But happily, history obliges; if you missed it the first time around, you're definitely going to get to see it again.

That's never truer than now, but what specifically about the Roosevelts related to today?

The vitriolic response to the Roosevelts reminded me of the response to the Obamas. It was deeply personal rage, disappointment, resentment and fear that went way beyond the political. FDR was hanged in effigy in country clubs all across America for being a traitor to his class; the rumor was that he was secretly Jewish—Franklin Delano Roosenfeld, as they used to write. That someone of his class would care about people who were suffering was otherwise inexplicable—inexplicable and sort of shameful.

Why did you choose Hickok to tell their story?

I didn't want to take on the voice of a figure as well known as Eleanor. While I wanted to be inside the Roosevelts' story, I wanted the voice to be that of an outsider. Lorena describes the Roosevelts in the book as people who had silver; they never bought silver. A friend said that to me once to describe her husband's family, and I thought, Oh, that's very different. I needed a narrator who could be mindful of that, and also understand what it means.

And I was fascinated by the idea that Eleanor's relationship with Lorena had been erased from history. Hickok was cropped out of most of the press photographs that included her. It's one thing to look back on that decades later, but what could it be like to be alive as that is happening? And what could it be like to be madly in love with someone who is married to your political hero? Lorena was, like Eleanor, not just a dyed-in-the-wool Democrat; she was a big FDR fan, which means her hero and friend was also her rival.

I was surprised by the discretion of the media. They were remarkably hands-off regarding both Eleanor's relationship with Hickok and FDR's affairs, most obviously with his White House secretary, Marguerite "Missy" LeHand.

The fact that he was in a wheelchair and married to Eleanor created a great deal of sympathy—perhaps not with the wider American public but certainly among male journalists, and then later among historians. Also, who wants to be married to Eleanor Roosevelt? She's a great lady, a saint, an icon. Well, that must be exhausting! [Laughs.]

And because Eleanor herself made it very clear that she was not, in fact, dismayed by Franklin's relationship with his secretary—Eleanor picked Missy for the job!—that made everybody else relax. It took some of the barb out of it for the journalists covering the White House.

That Eleanor picked Missy herself strikes me as pragmatic and highly evolved.|

She knew Franklin needed to be adored, to be served, to have women around him that had no other wish than to attend to him. None of that was going to be her.

In your novel, you suggest that President Roosevelt gave Hick a job in his White House to keep Eleanor happy. Is there proof of that?

There's no way that she was employed without Franklin's OK. And he obviously knew that she was in the White House in a bedroom adjoining his wife. I think to myself, You know, if my spouse had a lover in my house, even if it was a big house, I'm pretty sure I would notice. [Laughs.] I'd assume the same was true for Franklin.

Hickok and Eleanor shared political and social ideas, but their personalities were very different: Eleanor was modest and unshowy, well educated and from polite society. Hickok only finished high school, and she was as fierce, fearless and cynical as the male journalists she worked with. Other than her letters and journalism, what did you use to build her personality and voice?

It took me a while to find her voice, but fortunately there's a lot of space around Lorena. Facts are known, but there's lots people don't know, and much of what was written about her was written from the Roosevelt narrative point of view. So while what I read about her might seem warm and sympathetic, warm and sympathetic is not one's own point of view.

I think people felt they were being kind to Lorena, but the stance was always "poor little lesbian tugboat chugging along after the Roosevelt steamship." And I thought, None of us, in our own lives, are the little tugboat. We are the center of the story.

One of my favorite parts of Hickok's story is her adolescent stint with a circus, which included a relationship with someone who was then called a "hermaphrodite." True?

No. I feel bad about disappointing people regarding that story, but that's the fun part of being a novelist. All of Lorena's early childhood is based on known fact, including the rape by her father and running away from home at 14.

With the circus, there was a gap between the time Lorena leaves a terrible job cooking on a ranch and the time she starts high school in Chicago. I gave myself the opportunity to write about something I've always wanted to write about, the circus, which offered the opportunity for Lorena to see what being an outsider really looks like, to see more of the world and to see more of the ways in which people can be in the world—both harder and easier.

You include a few private conversations between FDR and Hickok, of which there is no record. How do you think he felt about his wife having a lesbian relationship? Would he have seen Hickok as a threat?

There's a fantasy we have that people who lived 50, 60 or 70 years ago must be completely different human beings. These were modern people! They didn't have cellphones or computers, but they lived in the modern world. And it was clear to me from Franklin's correspondence with other friends of Eleanor's, who were lesbian couples, that he was...I mean, he had, for a man of his background and personality, a sort of genial condescension, but also a lot of warmth and affection. I didn't think he would be threatened by Lorena.

What was the lesbian community like in the '30s and '40s?

There were upper-class women who knew each other, who had gone to girls' colleges and boarding schools—a significant number of presidents of the Seven Sisters colleges were in long-term lesbian relationships. It's so funny to read all these historians claiming Eleanor was a sheltered Victorian that wouldn't know a lesbian if she fell across one, and I'm like, How can you imagine that to be true, given all the evidence of her life?

But [lesbians] were careful; there was no socializing in public. You saw your friends at dinner parties, maybe people went away for part of the summer or had a country house. If you were working or middle class, there might have been a bar available to you. But it was dangerous. It's hard to understand now, but being exposed then was not just about reputation or someone looking at you askance; it was somebody beating you to a pulp and leaving you by the side of the road, and nobody would care.

In reading Eleanor's letters, what surprised you most about her?

The ways she continued to evolve as a person. She started as someone who certainly had progressive views for her class and background, but I would say she was mildly anti-Semitic—politely anti-Semitic. She wasn't going to put anybody in an oven, but she was also appalled by their vulgarity and clothes and pushiness. And she was quite anti-Catholic.

One of the letters she received was from an African-American woman who wrote that she and her husband had named their twins Eleanor and Franklin. Eleanor wrote back a very Eleanor Roosevelt letter, saying, "We are so charmed that you have named your delightful little pickaninnies after us." The woman, who was quite an exceptional person herself, writes back, "I am sure you meant this in the kindest way, and apparently you don't know that this is an offensive term and causes me pain. I would encourage you not to use that expression."

A lot of people would have been shamed by the letter, and a good person would have taken note of it and perhaps changed her style of speech. But Eleanor wrote to a long list of friends and said, "Here's what I've discovered: This is an offensive term. It's very important that we not use this ever again."

Is it correct to say that Eleanor got more radical after FDR died in 1945?

Absolutely. Her feeling that women should lead by their quiet, moral superiority was something she abandoned entirely by the time she was 60. She realized that wasn't getting anybody anywhere! [Laughs.] You need to get out and vote and run for office, you need to have agency in this world and make it a better place, and nobody can do it but you.

And yet here we are, in 2018, encouraging the same things. Do you have any thoughts as to why America embraced Eleanor so completely and could never do the same for Hillary Clinton? One could argue that Hillary was doing for Bill Clinton what Eleanor did for FDR, and much further along in history.

I don't know that I'm particularly insightful about the relationship of America with Hillary Clinton, but people outside the immediate Roosevelt circle did not know about [FDR's longtime mistress] Lucy Mercer. They did know about Missy, but that was clearly OK with Franklin and Eleanor—and not just OK in a stand-by-your-man fashion; these were two exceptional people who had figured out how they were going to do things. Eleanor was always fine with her role; she had goals and principles but no personal ambition. And that was in addition to her innate sweetness and guilelessness. Her championing of people who were suffering was genuine; it was never for anything except the purpose of improving their lives.

Now, why it should be necessary for America to have important and powerful women who are above all modest and devoted and willing to step back is another issue. I think there are things we expect from mothers that we don't expect from fathers, and I'm pretty sure that until men start bearing children, that's not going to change.

What in particular attracted you to Eleanor and Lorena's love story?

There was something very romantic to me about these women who fall in love in middle age. Even allowing for the fact that they might have been young and lovely at some point, they were not young and lovely when they met, but what they saw was beautiful to each other.

Hickok left journalism for Eleanor, and her career suffered for it. Their love story lasted only six years—from 1932 to 1938. When she died in 1968, her ashes were buried in her town's cemetery, in an area for unclaimed remains. It's a pretty heartbreaking ending for such a pioneering woman.

Lorena's friendship with Eleanor continued after 1938—not at an intense pitch, but they were never out of each other's lives. And she did become a successful writer again—she had a young adult biography of Helen Keller that was enormously successful. That helped me write the novel because there was something heartbreaking about the story otherwise. I had to overcome my own sadness about it.

How did you do that?

An old friend of mine once said, "Honey, there are no happy endings, even in long and happy marriages, because somebody gets hit by a bus." The chances of your going out at the same moment are very small. I had to accept that the more you love somebody, the more loss there's going to be. And also that love is never wasted. Then I could write my book.

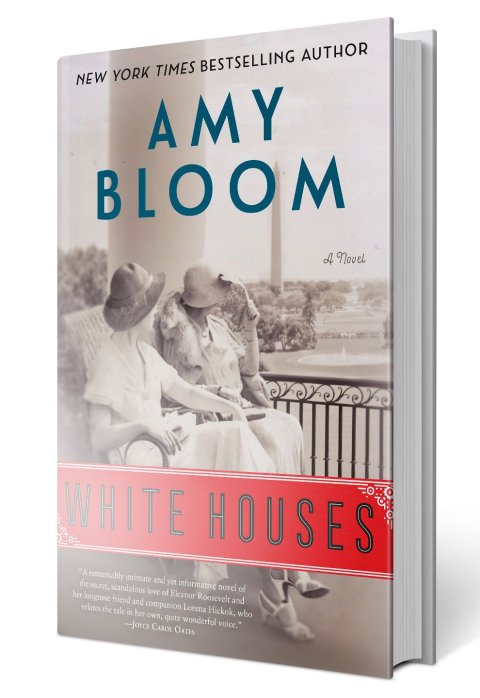

White Houses by Amy Bloom (Random House, $27) is available in bookstores and at Amazon.