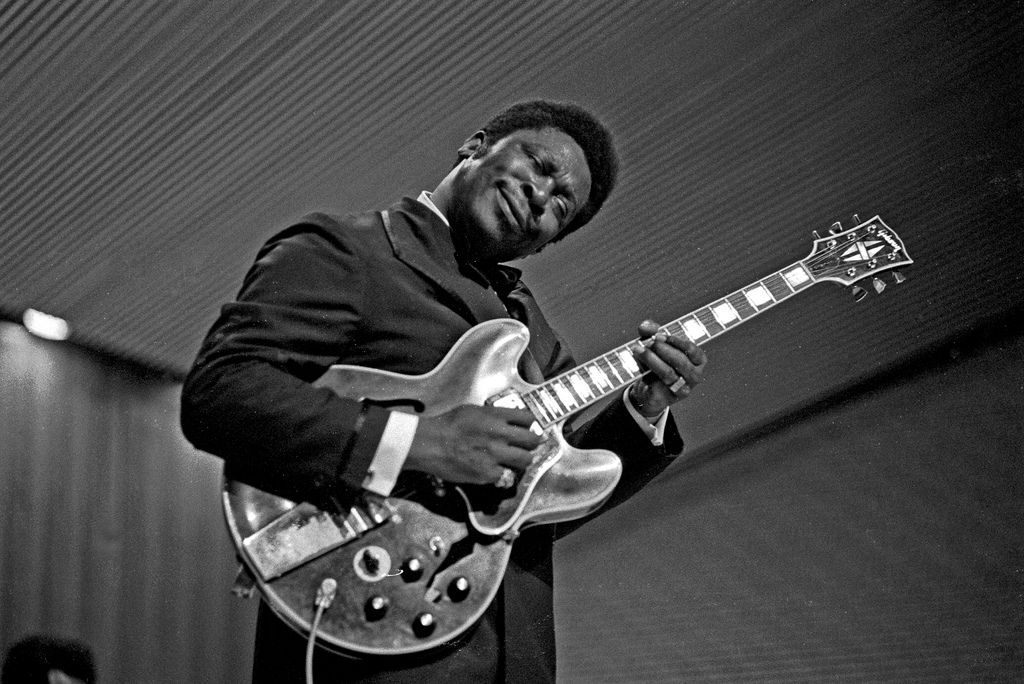

Newsweek profiled the late blues guitarist B.B. King, who died this week at 89, as he rose to national fame in 1968.

Although its form is rigid and its words are old, the blues has an uncanny knack of enlisting new apostles to sing its praises and convert fresh audiences. The source of the present high popularity of the blues is a new generation of young white people, captivated by the vitality of such urban blues men and their bands as B.B. King, Junior Wells and Buddy Guy. Last week, King was packing San Francisco's hippiedrome, the Fillmore Auditorium; Buddy Guy was nearby in Berkeley's New Orleans House; and Junior Wells was opening up the Northwest Passage in Vancouver's Retinal Circus.

Until less than two years ago, King, one of the great Chicago blues men, had never played for white audiences. "I used to play for the old and the poor," says the sturdy-looking, 42-year-old King, who once performed as many as 342 one-night stands a year in Negro clubs across the country. "The middle-class Negro thought that the blues was holding them back. But blues can't be too polished. Blues and correct English don't sound right."

Onstage, King is a gentle, patriarchal figure, with an air of world-weariness, like the Ancient Mariner burdened with the need to tell it all. He rarely moves except for a few telling gestures, as when he opens his hands pleasingly, or cups an ear to intensify a plaintive line in such songs as "Sweet Sixteen" or "Sweet Little Angel," sung in a mellow, light-weight, dusky-colored voice that can stretch up to an eerie funky falsetto.

He plays his guitar with the same subtle nonchalance, the shimmering bent notes exquisitely phrased, especially in the delicate upper register. He artfully builds every song from scratch, restraint and mellowness giving way at last to an explosive freedom in which the sparks fly from his guitar and, as in "Don't Answer the Door," he cries in a mixture of anguish and triumph, "Suffer! Suffer! Suffer!"

Like so many blues men, King comes from the Mississippi Delta, where he picked cotton, drove tractors and discovered the guitar. In Memphis after the war he spent three years as a disk jockey by day and a blues man by night. Soon after his first record, "Three O'Clock Blues" in 1949, he became a traveling man. "I can still do a week of one-nighters and not make what Ray Charles can working one place three nights a week," he says. "But I get to good places now, where you're not scared of getting hurt. Sometimes I'm bitter that we've been doing it for so long. My only ambition is to be one of the great blues singers and blues musicians. If Frank Sinatra can be the top in his field and Nat King Cole in his, why can't I be great in blues? Blues isn't dirty, it's American music."

Of Buddy Guy and Junior Wells, King says, "They're the young guys who are gonna have to carry on." Wells and Guy are in the vanguard of the newest blues style—theatrical, visual and spontaneous—stretching the limits of the once rigid form toward jazz, toward rhythm and blues. They demand a new freedom in which the importance of traditional lyrics is challenged not only by amazing musical virtuosity but by the act of performing in which the blues becomes a physical as well as a musical expression.

Mississippi-born, 33-year-old Wells, who came to Chicago when he was 12, learned to play the harmonica from the immortal Sonny Boy Williamson. He too plays it way out, with tremulous effects that recall trains passing in the night or in cascades of tone clusters, blowing into his harp as if he would blow it apart. When he's not playing, he's singing such songs as "Mystery Train" or Williamson's "So Sad This Morning," in a voice like a flamenco singer, cracked and abrasive, but with an underlying cheerfulness that mocks misfortune.

His mobility onstage, he says, is natural. "If the music's good, then it moves you around." Wells and his band recently made a State Department-sponsored tour of Africa. "We got to one place and they had banners saying, 'Welcome Home, Junior.' I told 'em, man, I said, this ain't my home, I live one block north of the Loop. Then they asked me what I thought of black power. I said black power is making it with Aretha Franklin."

Wells doesn't make a record unless Buddy Guy plays the lead guitar. "He makes blues moan," says Wells, "and say anything he wants." The 30-year-old Guy, who came to Chicago from Baton Rouge, La., spills notes from his guitar in runs too fast to hear, too complex to grasp, or, in a sudden change of pace, he will sustain one slow, tingling nerve end of a note after another.

He will start a song only to break off and begin another, at times muttering or erupting into gospel-like exhortations. He plays his guitar one-handed, or at arm's length, or behind his back or over his head, and he is as likely as not to end a set by leaving his band onstage, wandering off into the audience, trailing the long electric cord behind him, ecstatically singing and playing his way through the crowd and out the exit door, while the disembodied frenzy of his music still billows out from the loudspeakers.

"I wanted to be a boxer," Guy says. "But I got whupped a few times and decided you don't get whupped playing guitar." But he took the whuppings of indifference, almost quitting a year ago, until the interest of a new white audience changed his mind. Now he says, "I hope I'll still be playin' the blues when I'm an old man."

Like the ministry, the blues is a vocation, irresistible for better or worse. Says Wells, "When I was starting, everyone said, 'A young man like you ought to be playing jazz.' But the blues is my life and I'm stuck with it."

"I could change," says B.B. King. "So I'm just going on. I hope one day instead of hotel rooms to have a nice home. Maybe I'll have a little farm where I can put my father to stay with me. I've been scuffling for a long time. I think I deserve something."

This article was published in the June 24, 1968, issue of Newsweek, with the headline "The New Blues."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.