It's odd that we think of nostalgia as a feeling to indulge in. We play an old record, listen to a favorite sketch, relive a scene from a film—things that many might be doing now, given the many talented artists and actors who have died this year. Odd, because nostalgia is a kind of pain. The root of the word is shared with neuralgia, nerve pain, except that nostalgia is literally "home pain". It's an acute longing for the familiar.

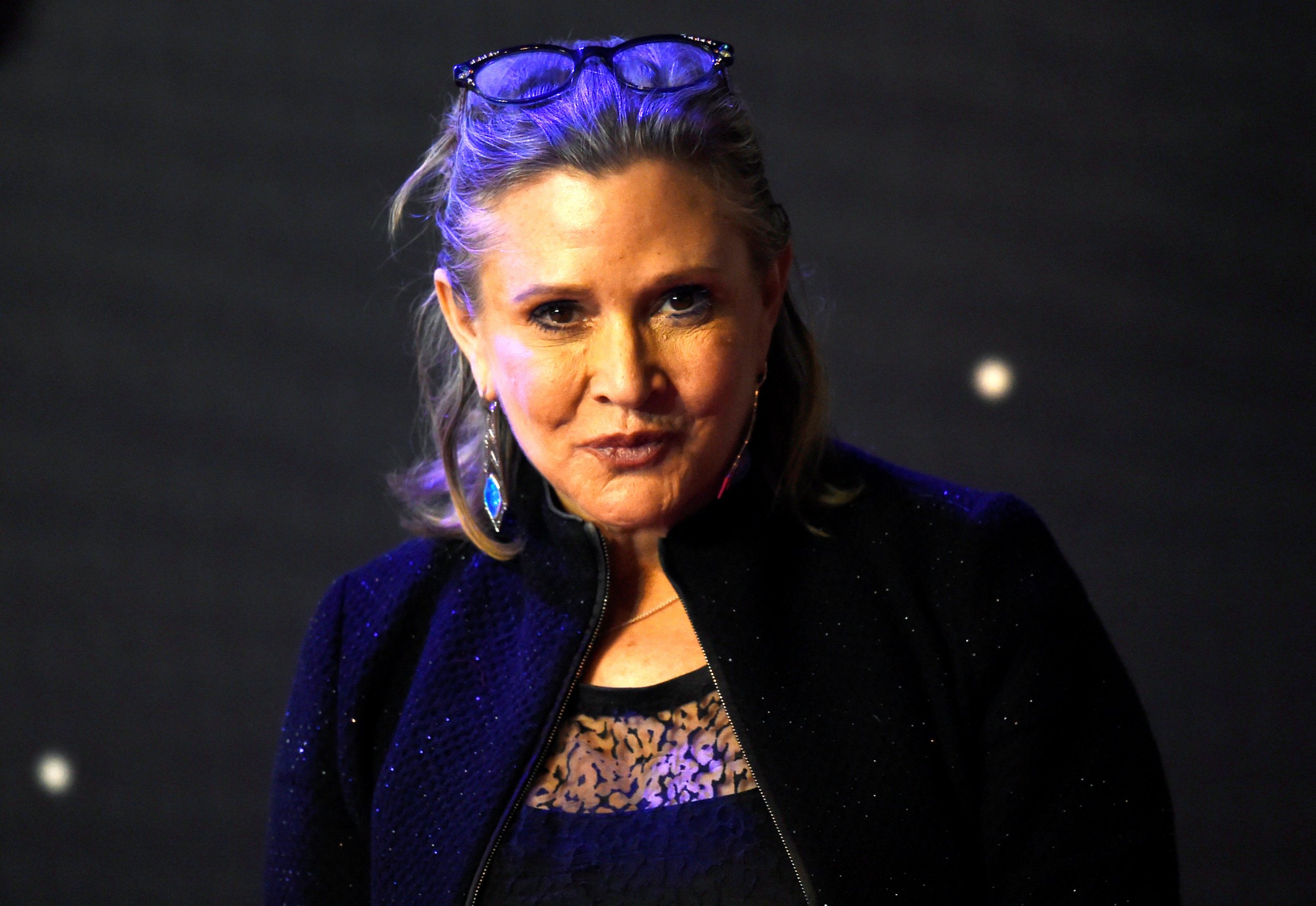

This is what celebrity deaths stir up in us: the loss of what's gone. And because celebrities often once captured powerful hopes and emotions in their music and performances, their deaths can be genuinely unsettling.

Their passing—prompting repeats on the radio and images on screen—can also stir up unfinished business hidden in the depths of our psyches. That can reignite a residue of unmourned emotion left from a different category of deaths: those who were very close to us, perhaps a parent, a partner, a child.

Sigmund Freud was onto this dynamic. He detected a risk when we lose someone with whom we are intimately bound. The risk is that with those deaths, we lose too much. We can't comprehend what's gone. The gap is overwhelming and consumes us in a miasma of grief from which it feels there's no escape.

The philosopher, Michel de Montaigne, caught the horror of this experience when he wrote of the early death of his closest friend and soulmate. "We were halves throughout. By outliving him, I defraud him of his part. I am no more than half of myself. There is no action or imagination of mine wherein I do not miss him."

Freud described this experience as a shift from mourning to melancholia—or depression, as it would be labeled now. It's as if we enter a state of mind in which everything is blackened by emptiness, absence, departure. We can't mourn the loved one because that person was, in a way, the whole of life to us. The residue of that ache may linger for years.

Then, someone famous dies. Suddenly, mourning becomes possible. The icon meant a lot but, unlike a parent or partner or child, was not half of us. And so it's a loss that can be felt. It precipitates an outpouring of grief—the death of Diana comes to mind —that is as much an unblocking of the deeper melancholia as it is sadness at the departure of the celebrity. The tears are real. But they are about more than the shock of the immediate news.

What this suggests to me is that there is a kind of art to mourning, though one we are hindered with today. We're not very well served by our culture because it tends to keep the genuine tragedy of death at bay.

You see it in the trend to hold celebrations for a life rather than funerals. The urge to do so is understandable: there is a time to give thanks. But there is also a time to mourn, and that might be denied.

Or death becomes hidden from us because, due to increased longevity, it happens mostly to those who are old—homed and hospitalized out of sight. That's perhaps why this year's celebrity deaths among stars who are relatively young is shocking. We've forgotten that death is found in the midst of life.

Wisdom-based traditions advise practicing mourning. Socrates said that philosophy is learning to die. Buddhists meditate before skeletons. Christians keep Good Friday. And it's good advice. Lesser losses—even the end of the day, the final page of a good book, the browning of the cherry blossom—can be opportunities to practice the fact of demise. They won't be overwhelming as big deaths can be. But we may still recoil from them and reach for a distraction rather than experience the difficult feelings. Maybe it's wiser to linger.

That's perhaps the departed celebrity's final gift to us: a moment to live their deaths and so know some of the feelings around our own. It's nostalgia in a healing sense: an embrace of life in all its tricky fullness.

Mark Vernon is a psychotherapist. For more information see, www.markvernon.com

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.