On Wednesday afternoon, the buses were rolling—again—in an effort to save the Senate Republicans' doomed effort to repeal and replace the Affordable Care Act.

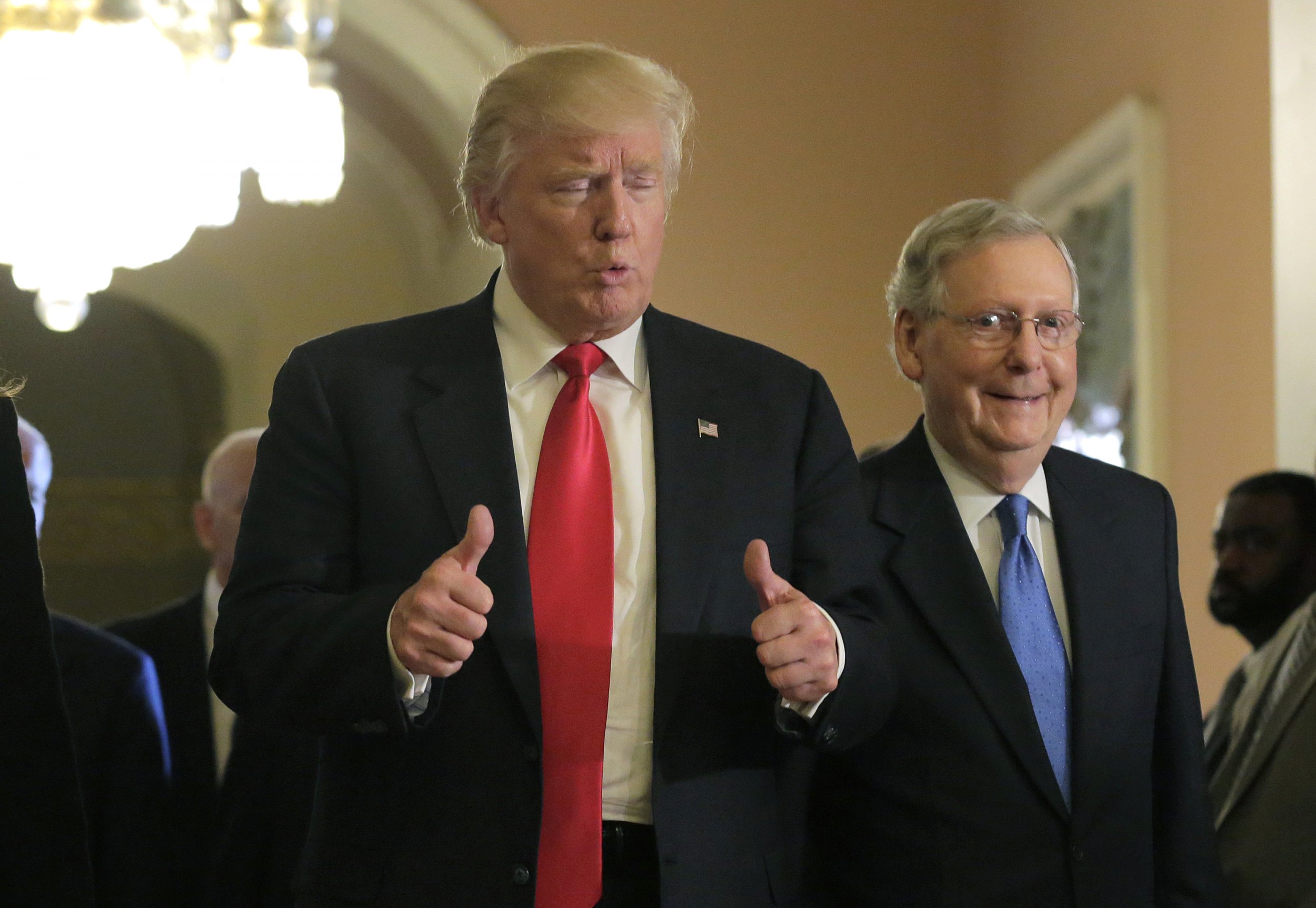

All 52 Republican members of the U.S. Senate were invited to the White House to discuss health care. It wasn't the first come-to-Jesus meeting, but it may have been the ugliest. Trump took a shot at Senator Dean Heller, one of the critics of the GOP health plan, joking that the Nevadan who is up for re-election next year might not be a senator much longer. Behind the scenes, there were also White House barbs at Senate Majority Mitch McConnell, for not being able to deliver the health plan votes, and ripostes from Senate aides placing failure at Trump's door. No wonder the usually Trump-friendly Drudge Report was blaring headlines like DC Hot Mess. Will They Botch Taxes Next? The site also touted stories with headlines like: Tensions reach new high between Trump, Republicans... President tells senators to cancel recess…

This may have been a Last Supper, but it wasn't the only tense meal under the new administration. There was another meeting with the entire Senate Republican Conference in the spring and countless smaller ones, including a dinner on Monday night where supporters of the latest plan were blindsided upon discovering that two more of their rank had turned against the bill.

Not only had McConnell failed to get the votes for a plan to repeal-and-replace Obamacare as of Monday night, when Republican Senators Jerry Moran (Kansas) and Mike Lee (Utah) joined Maine's Susan Collins and Kentucky's Rand Paul in opposing the measure, on Tuesday he hemorrhaged more votes. His idea of bringing a simpler plan just to repeal the 2010 Affordable Care Act and give Congress two years to come up with an alternative to be voted on next week seemed dead on arrival, as Collins, joined by Alaska's Lisa Murkowski and West Virginia's Shelley Moore Capito, said they wouldn't even allow the measure to come to the floor. Wednesday's meeting was more blame game than constructive.

Trump himself expressed the frustrations of his party on Tuesday when he said. "I'm certainly disappointed. Seven years I've been hearing repeal-and-replace from Congress. Been hearing it loud and strong. And when we finally get a chance to repeal and replace they don't take advantage of it."

The big question plaguing the Republicans isn't just why they failed to pass something they had promised for seven years, it is why they can't pass much of anything.

The country has a Republican president, the largest Republican majority in the House of Representatives since 1928 and a Republican majority in the U.S. Senate. Surely the Trump administration should be boasting more real legislative accomplishments by now. (Emphasis on the word real. The president's braggadocio about various executive orders and the confirmation of Justice Neil Gorsuch to the Supreme Court notwithstanding, this has been a remarkably unproductive six months in terms of passing legislation.)

The answer lies in questionable decisions by the White House and Republican leadership in Congress, as well as structural problems that have made it difficult for this Congress or any to be as productive as they were when, say, Lyndon Johnson passed the Great Society programs in the 1960s or Ronald Reagan signed his tax-and-spending cuts.

First, there are the bad decisions. One was starting with health care, as opposed to tax reform, which has wider support, or infrastructure, which has wider support still. Health care was always going to be a tough lift. It's bedeviled presidents for generations, beginning with Harry Truman's attempts to create national health insurance in the 1940s. Since Lyndon Johnson was able to pass Medicare and Medicaid, sweeping health care reform has proved a political nightmare. It led to the loss of control of Congress for the Democrats in 1994, when Hillary Clinton's health care plan didn't even have enough strength to come up for a vote. Barack Obama was able to push through the Affordable Care Act only barely, even with a huge Democratic majority in the U.S. Senate, and the fallout from it cost the Democrats control of Congress again. There was no reason to assume that this would be easy, given how ingrained the Affordable Care Act had become with its mammoth expansion of Medicaid.

Second, Republicans are dealing with a relatively narrow majority in the U.S. Senate: 52 votes out of the chamber's 100 members. That gives just a few senators power to derail legislation—even if there's no use of the filibuster, which raises the bar to 60 votes. In the case of health care, only two defections were tolerable for McConnell to be able to pass the vote 50-50 with the tiebreaker cast by Vice President Mike Pence. On Monday, the defections of Paul and Collins, combined with the medical absence of Senator John McCain—the Arizonan is recovering from blood clot surgery—was enough to delay the repeal-and-replace vote and to allow time for more opposition to galvanize. Once Moran and Lee weighed in, the bill was doomed.

It's possible to pass items on strictly party-line votes, which is what Obama did with the Affordable Care Act. But that only works if you have some wiggle room. As a general matter, big pieces of legislation require bipartisan majorities to pass, such as the Reagan tax cuts in the 1980s, welfare reform in the 1990s and the No Child Left Behind Act in the 2000s. No matter that all three pieces of legislation have their critics now: The point is that big bills need big majorities to be enduring. The late New York Senator Daniel Patrick Moynihan understood this. He begged the Clinton White House in 1994 to work with him and Senator Bob Dole on a bipartisan plan, saying: "I pleaded with the White House that in the Senate a measure of this importance either has 80 votes or 40 votes." No one listened.

The other problems hobbling Trump and the GOP majority are manifold and may even hurt Democrats if they take over one or both of the chambers. For a number of reasons, there's been a breakdown of the historic, linear process by which legislation is considered—going through the congressional committees, being publicly aired and then being vote upon in the respective chambers and then a conference committee that can hammer out the differences between the House and the Senate. In the case of health care, McConnell bypassed the committee system and handed it to a group of 13 members—all white men, which didn't help the optics—and came up with a bill that no one liked.

But McConnell is hardly alone. Most budget deals over the past few years have been hammered out in secret between the White House and the congressional leadership, bypassing the normal committee system. (Remember John Boehner famously trying to come up with a grand spending bargain with Barack Obama in 2012?)

Another problem hobbling Congress is the poor direction being shown by the White House. The next big item that's up on the president's agenda is comprehensive tax reform—a sweeping effort to simplify the tax code by eliminating many deductions and lowering tax rates in the process. The last time Congress passed such an effort was in 1986, over 30 years ago, and it made it through a Democratic House and Republican Senate and was signed by a Republican president. That seems impossible to imagine today. But part of the reason it worked is that the White House played a constructive role, offering its own version of tax reform through the Treasury Department, which was run by an old bull from Merrill-Lynch named Don Regan. So far, the White House has put forward only a one-page, hastily written note to Congress that is as much like a final product as a peanut is to a feast.

To his credit, House Speaker Paul Ryan is working closely with committee chairs to forge a tax reform plan and McConnell is doing the same in the Senate. But it's hard if not impossible to get something like this through if the White House doesn't have more of a plan. So many special interests are touched by this kind of legislation that in the 1980s it was dubbed The Showdown at Gucci Gulch. Regardless, Reagan and Democratic Senator Bill Bradley of New Jersey, Representative Richard Gephardt of Missouri along with Dole and House Speaker Tip O'Neill l were able to pass tax reform.

Likewise, when it comes to infrastructure, the administration still hasn't offered more than a skeletal outline of what it wants. This is a wasted opportunity. Democrats like Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer and House Minority Leader Nancy Pelosi have signaled that they want to participate in an effort to repair the nation's roads, bridges and electrical grid. Democratic constituencies are on board, including multiple unions. Republican governors love this plan, unlike the repeal-and-replace health care plan that many opposed. But it's a fairly low priority for a lot of Republican members in Congress, who are resistant to the additional spending and who repeatedly dissed Obama's stimulus plan as wasteful. To get them on board, Trump needs to have a more concrete—pardon the pun—proposal, and he has to sell it. So far, he hasn't. Treasury Secretary Steve Mnuchin and National Economic Council Chair Gary Cohn have been meeting with the Hill and industry groups, and are expected to put out a more substantial plan in August. But will that be too late? The Drudge Report is also blaring the headline Tax cuts become must-win for White House. That's true, and it's likely the last chance for something big this year.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Matthew Cooper has worked for some of America's most prestigious magazines including Time, The New Republic, National Journal, U.S. News ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.