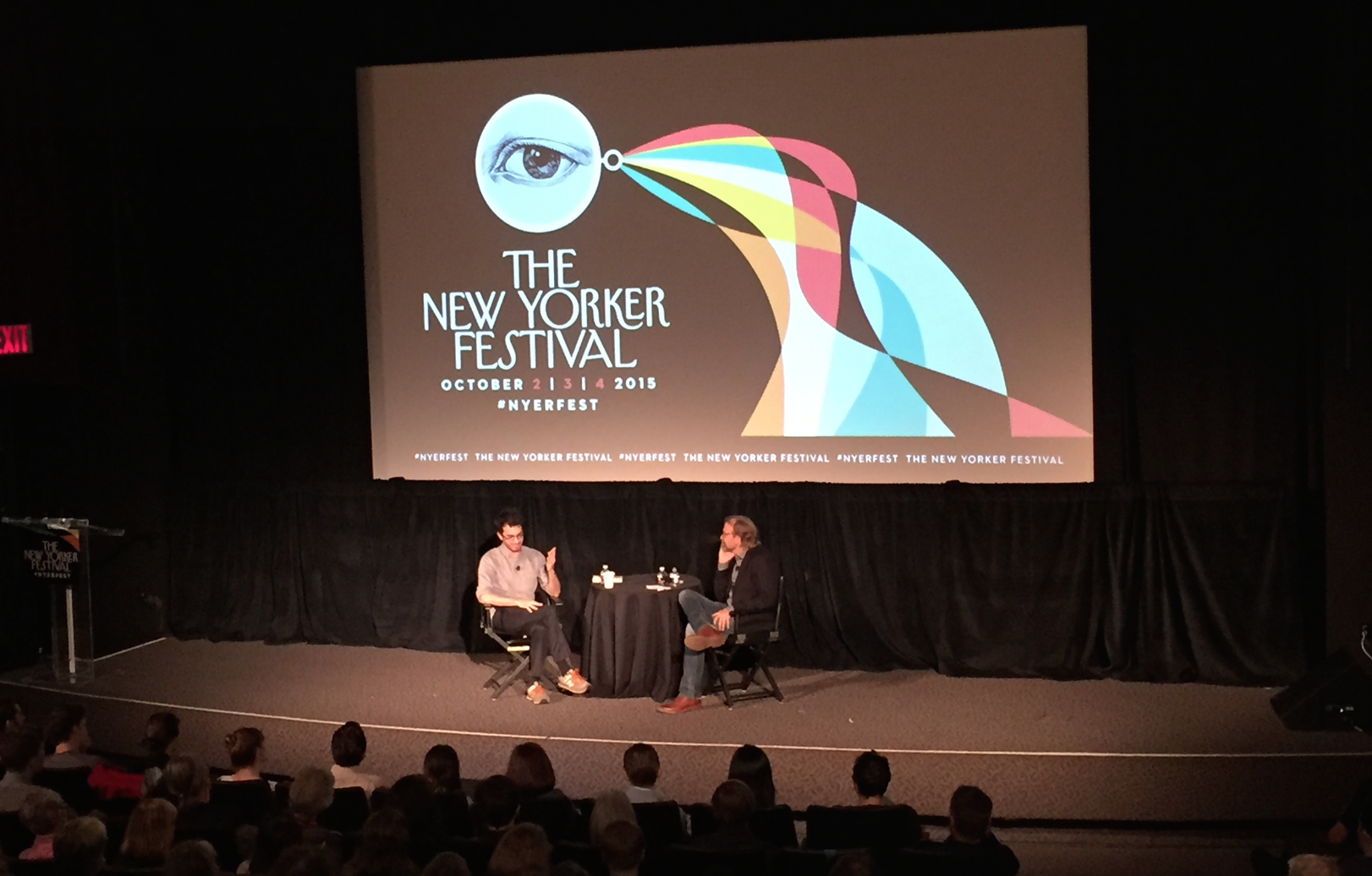

This past Saturday, George Saunders and Jonathan Safran Foer sat down for an hour-long discussion at Midtown Manhattan's Directors Guild Theatre as part of the New Yorker Festival. The two writers talked about all the usual things fiction writers talk about when they participate in such events—their writing process, the nature of art, what they're trying to accomplish through their work and so on.

But Saunders and Foer also touched on the state of America and, a little more obliquely, the state of American politics. Saunders spoke of how, in America, materialism has replaced religion, and how our growing need to quantify and profit from life can make important, abstract ideas—like the fact that there are things we don't know—seem "a little bit frothy." Foer told a story about the diversity he encountered in line at an amusement park with his kids and how beautiful it was. "That's an oversimplification of America," Foer said of the person in a turban, the black man and the white family in line in front of he and his kids, cheering each other on as they bounced on a trampoline. "But I think that despite the endemic problems, no one has succeed as well as we have in creating situations like that."

During the question-and-answer portion of the event, someone asked about the waning role of fiction writers as public intellectuals. "When 9/11 happened, I was so chagrined that fiction writers weren't turned to," said Saunders. "I know some very wise fiction writers and the culture didn't really turn to them."

It's 2015 and the culture still doesn't turn to fiction writers. Outside of Jonathan Franzen getting flayed on Twitter every few months, a stage in front of a few hundred like-minded liberals at a festival put on by a highfalutin liberal publication is the farthest a fiction writer is likely to advance into popular discourse. It's a shame, because as the country takes stock of itself this election season, we'd do well to give writers a wider berth to comment on the issues. After all, they've made careers out of articulating the American condition. You'd think they might have some thoughts on the circus we're currently mired in. As it turned out over the weekend, they do.

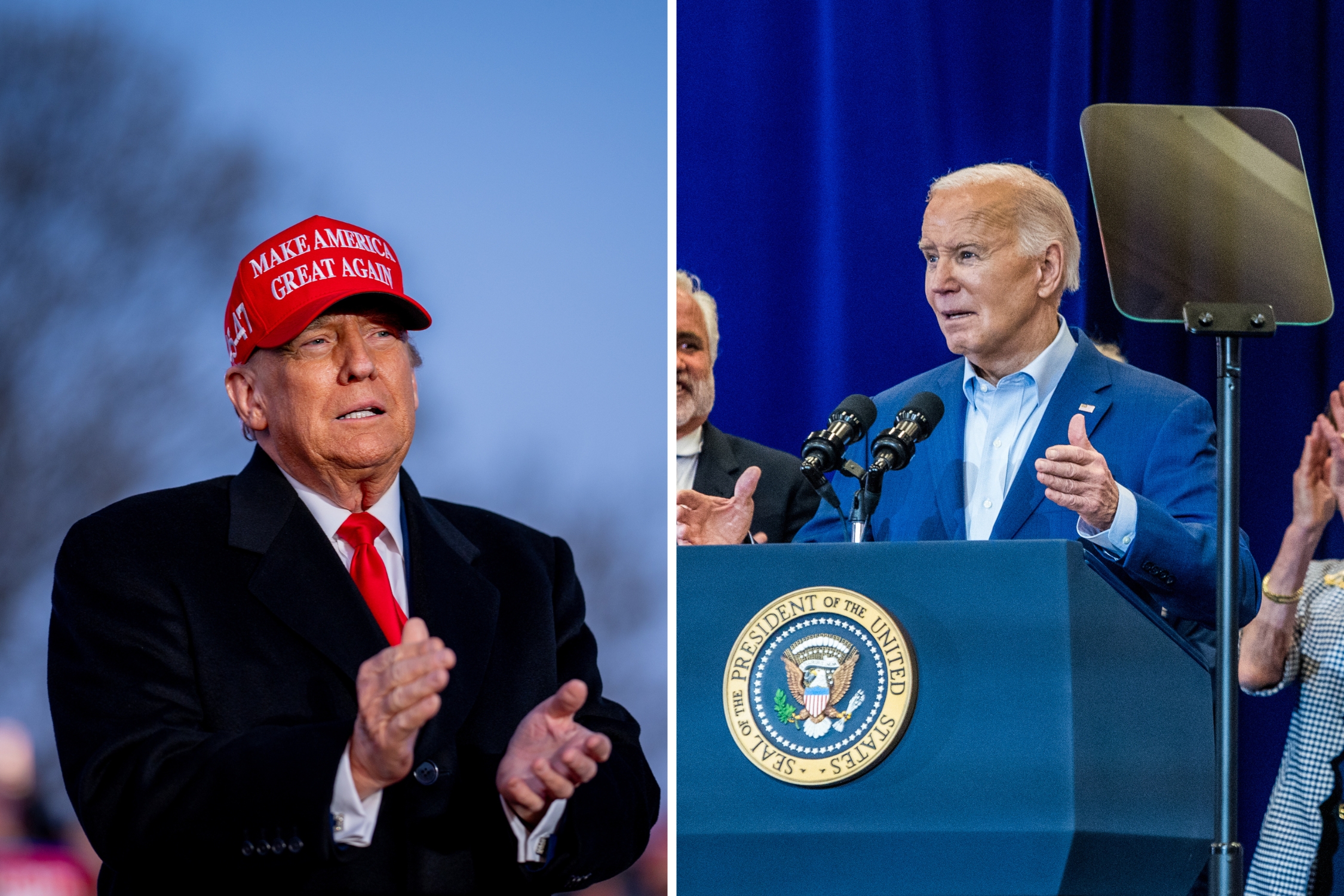

Earlier on Saturday, at the Gramercy Theatre, novelists Junot Diaz and Aleksandar Hemon, who were born in the Dominican Republic and Bosnia, respectively, and have written extensively about the immigrant experience, spoke passionately and at length about the "endemic problems" Foer had referred to. Here's the way Diaz described the appeal of how Donald Trump, whom neither writer thinks very fondly of, is using xenophobia to win over Americans:

We're in a situation where people are happy to get the psychic capital this kind of hateful politics produces. There is psychic capital gain when you're not the one at the other end of the machete. It's the most primitive form of psychic capital, and yet, in a world that is so unequal, where real capital is being taken away from you left and right, you're forced to sup on the thinnest gruel of psychic capital of the horrors of nationalism. This is what's happening in the United States with our mainstream politicians. They're now like, 'Okay, we've got to up the psychic capital because we've basically taken everything away from everybody, so the only thing we've got to throw [them] is bread minted from this horrible, horrible grain.

And on the role immigrants play in the "project" of America:

Communities come to this country and absolutely add a tremendous amount of their life energy to the project of this country, for which they get no recognition and they get nothing for. For me, that is the perversity of this discussion. Folks come and sacrifice their lives, and really for the most part add nothing but value, but they're demonized for it. It's a very strange set of politics we have, and a very strange set of political practices we have. And yet, without us, as you know, this is a nation that falls to pieces. America is as addicted to its immigrants as it's addicted to its cocaine. If you withdraw immigrants from this country, America would just be a shivering, shitting-itself wreck.

Though it may be easy to dismiss Trump's brain-dead stance on immigration, Hemon warns against ignoring him. "What I've learned is that you never dismiss the clowns in political discourse," he told the audience. "If you think this is crazy and cannot possibly work, now is the time to get worried—because what you cannot imagine is what one should be scared of."

Even more inscrutable than immigration is the epidemic of lone shooters whose destruction of our communities has become routine. It's an issue for which not even narrow-minded politicians can devise a palatable solution. Don DeLillo addressed this on Friday night during a conversation with New Yorker fiction editor Deborah Treisman:

This is World War III. It's a fact. It's everywhere. Innocent people are being slaughtered everywhere. It's terrorism that is expanding…almost geometrically. What's left? What happens next? We have our lone shooters, our individual terrorists. Where do they come from? What motivates them? I think in many cases the gun is the motive as well as the weapon itself. A gun makes it possible for an individual, a man—a young man, usually—to make sense of everything that's happening to him, either in three dimensions or in his mind. It gives him a motive. It gives him a sense of direction. It's a substitute for real life and it's the way he will choose to end his life, as well as the life of innocent people, of course.

The 78-year-old DeLillo is one of the most prescient literary minds of the 20th century. His 1985 novel, White Noise, foretold multitudes about our relationship with technology. At the heart of that book was a gun, the destructive power of which proved inevitable. Three years later DeLillo published Libra, which explored the mind of Lee Harvey Oswald, a man with whom DeLillo became borderline obsessed, and whom he spoke about at length on Friday night. Oswald is an antecedent to the lone gunmen of today, but, again, one thing lies at the heart of the matter.

I think many of these young men have the same sense [as Oswald] of being nowhere. We have to mention the fact of imitation. Are they doing it because other people did it? Did other people give them the idea to do it? What is in such a man's life that allows this? It's an outlet, perhaps, for his anger, for his fear, for his disappointment, for the fact that he hasn't quite figured out who he is. The gun. It's the gun. This is what gives him the idea. Does he buy the guy because he wants to shoot somebody, because he wants to kill 12 innocent people? Or does the gun exist to begin with? I would like to imagine that in most cases it's the latter. He has the gun because he's an American, and he's allowed to buy a gun. It's the gun that is the motive. This is crucial. If he didn't have it, what would he think? What would he do to find that kind of disastrous satisfaction? He wouldn't know what to do. He wouldn't start punching people, would he? He has to have the gun. That's in the middle of it all.

From Harriet Beecher Stowe's Uncle Tom's Cabin illuminating the brutal reality of slavery, to Upton Sinclair's The Jungle doing the same for the meatpacking industry, fiction has a long history as a tool for change. But as novels are shoved further and further to the periphery of popular entertainment, so too are the voices of those who write them. In 2015, to be an influential fiction writer means only to wield influence within a niche audience of people who are already of the same mind. "Politics is a business conducted by serious people who do it in a different domain," Hemon said, addressing both Diaz and the audience. "I may want to argue with some right-wing asshole about something, but all the people I get to talk to are like you."

Allow Diaz to elaborate on how we got here:

Any country that spend the last 30 years defunding arts education at the public level has more or less structurally guaranteed a population that gives no ethical authority to artists. Part of the reason that our voices aren't going to carry very far as artists is that most people have very little arts training, and therefore think, 'Oh, what are these damn artists talking about?' The only authority our country grants is to people with power and people with money and people with fame. Literary fame don't count for shit. Literary fame is like the ruble in the economy of fame. It's like the Dominican peso. It doesn't trade for a lot.

Both Diaz and Hemon agree with Saunders that discourse in America has become one-noted and that there is little room for any sort of nuanced discussion of complex issues. Immigration and gun control and whatever else must instead be simplified—Immigrants are coming in, so let's build a wall!—regardless of what is lost in the process. So despite the insight they may be willing to offer, it feels naive to even posit that fiction writers should occupy greater space in the contentious back-and-forth in which the country is currently embroiled. In fact, as Saunders might say, the suggestion seems a little bit frothy.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ryan Bort is a staff writer covering culture for Newsweek. Previously, he was a freelance writer and editor, and his ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.