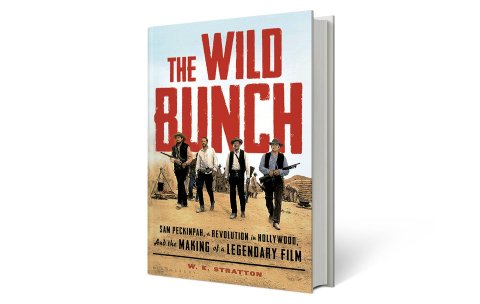

W.K. Stratton was 13 when The Wild Bunch was released in 1969. In that pre-internet time, movie theaters were a prime option for escape, and in director Sam Peckinpah's radical Western Stratton was transported to a landscape of "agony and dirt...The way the violence was portrayed really got my attention," says the author of The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film (Bloomsbury).

Visceral, bone-crunching brutality is so common now that it's hard to fathom the effect The Wild Bunch had on its first audiences. The film was polarizing—equally reviled (a few early viewers reportedly left the theater to throw up) and celebrated. Many in a new generation of filmmakers, including George Lucas and Martin Scorsese, were thrilled by it. Kathryn Bigelow, who would go on to direct the Oscar-winning The Hurt Locker, described its effect as a paradigm shift: "It took all my semiotic Lacanian deconstructivist saturation and torqued it." Quentin Tarantino has called the final shoot-out "a masterpiece beyond compare."

Peckinpah's innovative quick-cut editing (of a staggering 330,000 feet of film) and his use of slow motion introduced a new vocabulary to violence, with that final sequence a near ballet of bullets and blood. And though Sergio Leone had introduced what's come to be called the dirty Western in 1964—with A Fistful of Dollars starring Clint Eastwood—Peckinpah's Oscar-winning screenplay (written with Walon Green and Roy N. Sickner) added existential layers: the angst of encroaching corporate America (via the railroads) and the ultimate meaninglessness of the lives of the film's central outlaws: Pike Bishop (William Holden), Dutch Engstrom (Ernest Borgnine), Deke Thornton (Robert Ryan), Sykes (Edmond O'Brien), the Gorch brothers (Ben Johnson and Warren Oates) and Angel (Jaime Sanchez)—as merciless a bunch of "heroes" as American cinema had produced.

The movie, Peckinpah's fourth, takes place in Texas and Mexico in 1913, on the eve of World War I, when technology is beginning to transform the West. As critic Roger Ebert, an early devotee, wrote: "The mantle of violence is passing from Pike and his kind, who operated according to a certain code, to a new generation that kills more impersonally, as a game, or with machines."

Stratton's book examines the history of the Western and details the ambition and, at times, lunacy of making what has become an American classic. Newsweek spoke with him about the film's legacy and Peckinpah's complicated genius.

You write that The Wild Bunch "placed a tombstone on the grave of the old John Wayne Westerns." What are some examples of how he did that?

Peckinpah took the revisionist Western to its ultimate home. As one of his friends said of the characters, "These are really bad men." There's nothing redeeming about them, and yet we end up caring about them—deeply. That changed the whole dynamic of the Western.

We'd gotten away from Tom Mix and the idea of the white hat—or purely good hero—decades before that, but there was always a little something good in the characters. Pike and his group are killers, and they kind of get off on it. That opened the door to some really interesting films, including Peckinpah's own The Ballad of Cable Hogue [1970] and Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid [1973], as well as Eastwood's The Outlaw Josey Wales [1976] and Unforgiven [1992].

Peckinpah was also reacting to the sanitized ways that violence was being portrayed in popular TV Westerns like Gunsmoke.

He made the film in 1968 and into 1969—a terrifically violent time in American history. How much of that played into the film?

His friend Jim Silke told me he thought Sam never shot a single foot of didactic film. So I don't think he was intentionally going after an allegory of the 1960s. However, nothing happens in a vacuum, and this movie company went to Mexico to film The Wild Bunch just about the time Martin Luther King was assassinated. And then they wrapped up shortly after Robert Kennedy was shot. And in the middle—though no one in America knew it for a year or so—was the My Lai Massacre. Plus, we thought the Russians were going to blow the whole world up. It was scary times, and there was violence everywhere—I felt that as a kid.

So while I don't think the film was a response to current events, when Pike Bishop says to the corrupt Mexican general Mapache [who offers to pay Pike for stealing a cache of American guns from the military], "We share very few sentiments with our government"—well, there were people seeing the nightly news footage of napalm being dropped on Southeast Asia and thinking the same thing. Unlike many of the Westerns that had come before, the patriotism is gone.

There's also that scene, when Pike and his men are stealing the guns off the train: The American soldiers are all inexperienced kids—like the 19-year-olds being drafted into Vietnam—with incompetent leadership. They don't know what they're doing, and they get shot all to hell. That's how a lot of us felt about Vietnam.

The film's biggest villain, of course, is the railroad man, Harrigan, who hires Thornton to track and kill Pike and his bunch. The carnage of the first shoot-out—when dozens of innocent townspeople are slaughtered—is his doing.

Harrigan is the corporate capitalist—the sort of man Peckinpah hated, like the studio executives he was always battling. And by the way, Harrigan is also the one who ends up a success in the end, right? It's hardly ever pointed out that Harrigan gets what he was after—they are all dead.

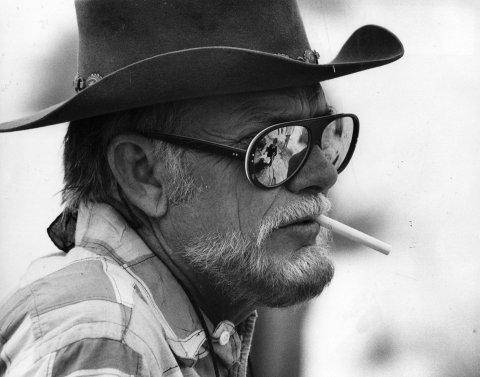

Your book paints Peckinpah as an inspired artist but also a maddening and violent man, not unlike William Holden's Pike.

He was a complicated person—a walking contradiction, to quote the Kris Kristofferson song. I don't think there has ever been anyone who has worked in Hollywood who mastered all aspects of directing motion pictures better than Sam Peckinpah, who was a true auteur. He could write great screenplays, he knew all the technical things, he knew how to edit and direct actors—he had all those gifts going for him. But he did some horrible things, all exacerbated by alcoholism and, later, cocaine. He had a deeply ingrained paranoia and a violent, violent temper. He always carried a gun and later became a knife thrower; he acted out in bar fights and was known for sucker punches. [His friend] Max Evans said once, "Every woman Peckinpah was with he ruined."

So you can't approach The Wild Bunch without seeing it as an artist—someone who did these terrible things—studying his own tendencies. The self-reflection of Pike, which William Holden accomplishes without speaking a word—What have I messed up here, who have I hurt, how did we end up here?—are things I'm sure Peckinpah thought about himself.

The Wild Bunch was a revolutionary anti-hero bloodfest for sure, but hadn't Arthur Penn introduced similar things in Bonnie and Clyde in 1967?

Bonnie and Clyde certainly took the anti-hero to a new level, and the violence in Penn's film was groundbreaking. But there was something artistic about it—particularly that final shoot-out, which was almost like a sex scene between Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway. Peckinpah didn't want any of that; he wanted agony and dirt. He was a fan of Leone's Eastwood films, the ones where if a fly landed on a guy's face while he was talking, it stayed there. You can almost smell the bodies in those films.

I was surprised to read that Peckinpah considered Tennessee Williams his greatest influence. Their work, at least on the surface, doesn't seem to have much in common.

The psychology of the characters, and looking at them as psychological studies, and what happened to deform them in the way they are—I think that's it. There aren't a lot of good people in Williams's plays, or people who aren't very troubled. What Peckinpah saw was that you don't have to dress anybody up, you can dress people as they really are.

The Wild Bunch opens with one of the most arresting scenes in film: As Pike and his group ride into a town, a group of kids are watching two scorpions they've tossed into a red ant pile. They then set the whole thing on fire.

I think what Peckinpah was getting at is that there is something deeply rooted in human beings that is disturbing—something really dark in all of us—and these dark things come out and we have to deal with them. There's some aspect to our psyche that enjoys things we probably shouldn't be enjoying.

In fact, he intended the film to be cathartic—a way of purging violent feelings. He later realized he'd made a mistake. Did he ever regret making the film?

He understood he had inadvertently created a kind of pornography. He mentioned The Texas Chainsaw Massacre in a BBC interview; that kind of splatter film was porn, and it took off after The Wild Bunch —there's no escaping it. There was violence in his subsequent films, but never to that extent.

He would sometimes disavow the film later, but that probably had as much to do with his later work, and some of it—including Junior Bonner, Pat Garrett and Bring Me the Head of Alfredo Garcia—is really fine. But they never got the same kind of attention. [Peckinpah died in 1984 and released his last film, The Osterman Weekend, in 1983.]

Once VHS came along in the late '70s, I started watching all of his movies again and again. I came to think of him essentially as a poet who instead of using metaphors being written down on the page, [they] were on the screen. Everything in his movies, when he was at his peak, was what it was, but it also had meaning beyond that.

What did you see beyond The Wild Bunch's obvious story of outlaws facing the end of their way of life?

It's an elegiac thing about the end of the West, yes, but it's also a cautionary tale about the deadly effects of technology. Those four guys in the final shoot-out are able to kill 100 Mexican soldiers because they use repeating rifles, pump shotguns, semi-automatic pistols and a machine gun. And there's that scene of Angel being dragged behind an automobile: Technology is dragging us, not the other way around.

But it's essentially a love story—kind of a weird one—or a romantic triangle, between Pike, Dutch and Deke, who is the spurned lover; he was part of the crew, Pike's right hand, before getting caught and sent to prison. Deke's now hunting the bunch for Harrigan, with a crew of scurrilous bounty hunters, as a way of getting out of prison. Dutch has moved into Deke's spot. They're not gay, but they are certainly more emotionally attached to other men and really can't connect with women.

Aren't most Westerns essentially love stories between men?

Absolutely. And then if you get into the novels of D.H. Lawrence [Women in Love], and subsequently Leslie Fiedler's readings on classic American literature 1960's Love and Death in the American Novel]—if you look at Moby Dick and Huckleberry Finn, it's really about men who can't relate to women, and they're out in the frontier.

Right, and there are no significant roles for women in this, or in most classic Westerns.

One thing I'll give to both Leone and Peckinpah: They didn't try to artificially insert a female character into stories about men, like the classic Westerns before then did.

If you're looking for strong female characters, check out Julie Christie in Robert Altman's McCabe & Mrs. Miller—it's one of the great feminist Westerns. I don't think Peckinpah had a great influence on Altman, but there are sequences in McCabe that were invented by Peckinpah.

The first strong, authentic female characters I noticed in the genre, at least as written by men, were in the work of Larry McMurtry, who knew the cowboy world—he was raised on a ranch in Texas—and called bullshit on the mythology of the West.

I was reading all of McMurtry's early books in college, even in high school, and I thought, Oh man, this guy is doing it. He opened a lot of doors for people like me, to look at what surrounded us, to see the bullshit mythology, as you call it, and move forward.

The Wild Bunch also crushed the mythology of the Western. Nothing was the same after that film. There were a few normal Westerns with John Wayne, but they were mostly failures. His best work, I think, was in his last film, The Shootist, in 1976. Don Siegel did a great job with that, but I can't imagine it being made without The Wild Bunch coming first.

The central code that exists between Pike and his men—that you support the men you ride with, no matter the atrocities they commit—is fundamental to the film.

Right. And that certainly is part of the American fabric, in any number of ways, whether it be cowboys or cops or politicians or soldiers.

There's that other cowboy code, of freedom above all else. That don't-fence-me-in mentality has led to a lot of fencing out.

Another 1960s film, Easy Rider, a Western in its own right—an ironic Western—has that brilliant scene with Jack Nicholson, around the campfire, and he's talking of freedom, and that's what it's all about. You're gonna get in a fight if someone says they're not for freedom. But if you look at the way life really works, we don't like freedom too much. We're more into repression.

Each of the actors gives one of the best—if not the best—performance of their career. It was a critically-acclaimed comeback for Holden, who wasn't even nominated for an Academy Award. The old-school cowboy, John Wayne, won that year, for True Grit.

It's unbelievable that Holden wasn't recognmized. And Wayne was much better in The Searchers or Red River or The Quiet Man. Maybe the Academy felt guilty; he wasn't going to be around much longer, and he needed one Oscar in his life. Dustin Hoffman and Jon Voight kind of split the votes for best actor for fans of Midnight Cowboy [which won best picture and director for John Schlesinger]. What a year 1969 was for movies!

More than any other genre, the Western personifies America, and it keeps getting reinvented. Are there any you particularly liked in the last 10 years?

There's something fundamentally American about the unknown man who rides into town, whether on a horse or a motorcycle or in a spaceship. And, yes, interesting takes continue to be made, like Tarantino's Django Unchained. One that I liked more than a lot of people was The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford, with Brad Pitt as Jesse James. Our old friend Sam Shepard, may he rest in peace, is Frank James. It wasn't an action film, and I think some people may have been disappointed in that.

I can predict your answer to this, but I'll ask anyway. How do you feel about Mel Gibson remaking The Wild Bunch?

Obviously, Gibson is not a filmmaker of the scope of Sam Peckinpah, so whatever he will make will be less of a product. But why not do something else? There's no reason to remake Citizen Kane or 400 Blows or La Strada. Why remake a classic?

The Wild Bunch: Sam Peckinpah, a Revolution in Hollywood, and the Making of a Legendary Film is available here.