This article first appeared on the London School of Economics site.

Their sights set on winning the next presidential election, Democratic Party campaign consultants are scrutinizing the potential 2020 electorate through straw polls and reading the signs like seismologists inspecting a scratching needle on a constantly rotating drum.

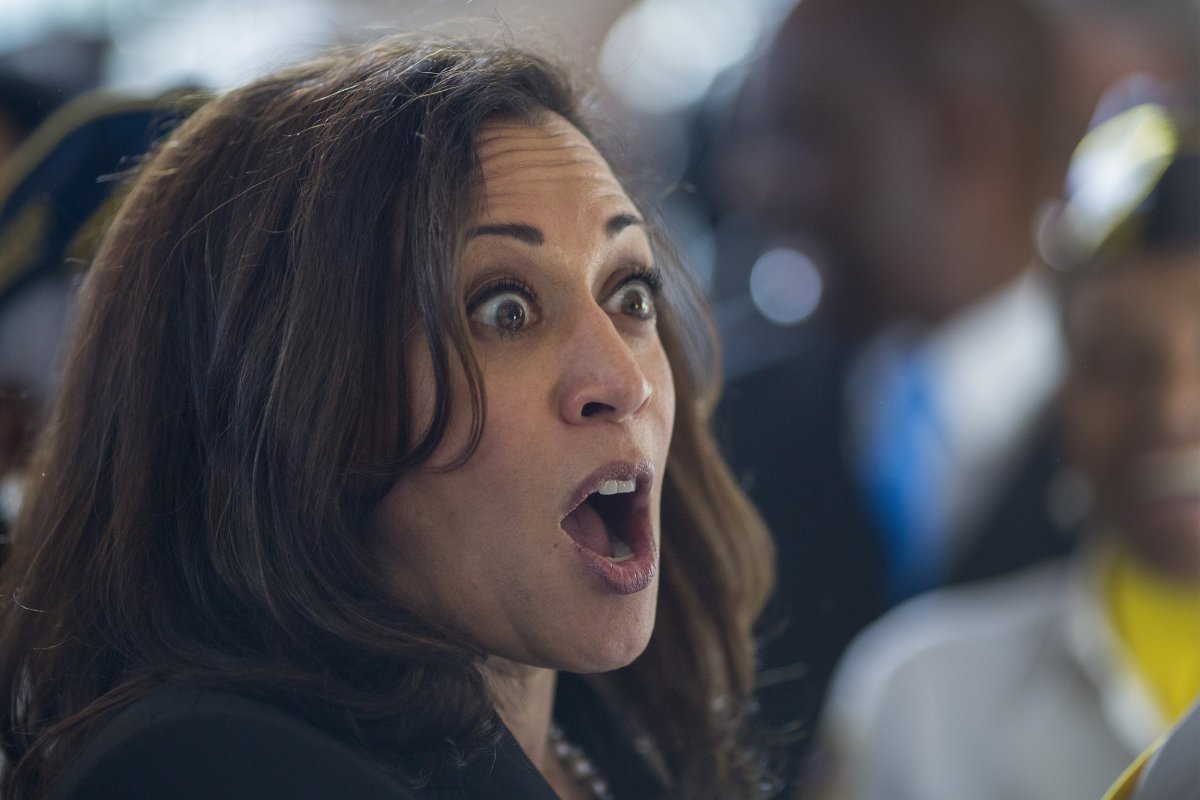

Can the center of gravity be shifted to someone like Kamala Harris, US Senator from California—a "new progressive," biracial Congresswoman whose pragmatism as state attorney general helped her attract votes from Hillary Clintonites?

Or how about Eric Garcetti, current mayor of Los Angeles, America's second-largest city? He's a virtual unknown outside California's borders, much as the name "Deval Patrick," two-term governor of Massachusetts whom President Obama apparently favors, rings bells faintly outside New England.

The 2016 presidential election threw prior norms about who can win the presidency and strategies for carving a path to the office into disarray.

With only one test case, it's impossible to know whether 2016 was an outlier or whether the unwritten rules have changed permanently, but it's clear that the interplay among candidate competitiveness, current political party rifts, and California's electoral rules will help determine the final line-up, which will be forming over the next two years.

Competitiveness was once measured primarily by elective experience and fundraising ability. Those who had been battle-tested through lesser campaigns, the reasoning went, would be prepared for a bloodier national contest.

Celebrity alone did not a serious candidate make, but it could launch one into position for a later run at the office (think Governor Ronald Reagan). Now that businessman-turned-television star Donald Trump has successfully converted his celebrity into political success—with neither political credentials nor the traditional fundraising machines that elevated Obama, Bush, and (Bill) Clinton—upstart presidential aspirants are perceiving new passages into the Oval Office that could not have been imagined a few years ago.

Mayor Eric Garcetti is a case in point. No candidate has successfully converted a big city mayoralty into a successful presidential bid, although New York City's Michael Bloomberg and Rudy Guiliani have tried.

Garcetti, a youthful environmentalist (he was born in 1971), an energetic Rhodes scholar who earned degrees from Columbia, Oxford, and the London School of Economics before entering Los Angeles politics, and son of a Mexican-American father and Jewish mother, thinks there may be path, though he has not admitted that he wants the office.

He recently asserted that, "the rules have changed, absolutely," and questioned whether there was really a difference between being governor of a state with 3 million inhabitants and being mayor of a city with 4 million people who are also living in the seventeenth-largest economy in the world.

He has a point, but unlike his gubernatorial counterparts who oversee state political systems with strong federal ties, his city possesses no votes in the Electoral College (L.A. is not a national staging ground), and his is not a household name. That has not stopped Democratic donors and party elites from whispering sweet nothings into his ear, wooing him as a potential candidate.

Political experience has been an important informal qualification for major political party presidential nominees that Donald Trump has challenged seriously. Except for General Eisenhower, of the dozen other US presidents elected since the start of World War II, all either served in Congress or were state governors.

The uncoupling of distinguished political service from party nomination began to falter with Barack Obama, for although he had served as an Illinois state legislator, he had been a US Senator for less than two years when tapped to run for president.

Senator Kamala Harris now finds herself in the same, curious position as then-newly-elected Senator Obama did in 2004. Surely her own calculus about timing will be less influenced by the impetus to gather more experience and governed more by her read of the political landscape in the coming months, the intensity of recruitment by Democrats, and if it comes to it, "to strike while the iron is hot."

A new feature of the political landscape that any Democratic Party candidate must navigate is the ideological rift that now divides Democratic Party centrist progressives (call them the Clintonites) from the further-to-the-left Bernie Sanders supporters.

Weary of politics as usual and fired up by anti-corporatist rhetoric, Sanders holdovers are pursuing single-payer health care and challenging current powerbrokers and big donors who have the independent means of kick-starting the campaigns of relative unknowns.

Nationwide, Sanders supporters are single-mindedly pursuing state party offices, and in California they came within striking distance of installing their preferred leader as the state's Democratic Party chair in 2017. If they succeed in the next two years, then Clintonites' chances of endorsing their own candidates will at best be reduced sharply.

Regardless of which faction wins that intraparty fight, California could play a pivotal role in choosing the next president if it moves its primary election to the beginning of the process, but emphasis should be placed on could .

Since 1946, California's presidential primaries have been held in June with four exceptions: 1996, 2000, 2004, and February 5th, 2008, the earliest primary in state history.

Although voter turnout increased as interest in the campaign spiked in 2008, other states also moved up their primaries to stay competitive, with 15 of them instantly diluting California's strength by holding their primaries the very same day. Considering that Californians had limited influence over the national outcome, the $97 million cost of a standalone election, and a reluctance to initiate the California general election campaign season in February or March, state officials moved the primary back to June.

Now the California legislature is ready to replant its primary in March once again, and to enable the governor to schedule an even earlier election should other states leapfrog ahead of California.

Governor Jerry Brown has not yet signed the bill into law, and there is some concern over whether the state will be penalized by party organizations for acting without the parties' official blessing. After all, presidential primary elections are political party affairs through which the voters actually select state delegates who will support a designated candidate at the party's national nominating convention.

California could be sanctioned if it violates party rules regarding the national election calendar, which has yet to be finalized. Moreover, if a candidate in either party has not secured enough delegates to clinch the nomination by June, California could be the powerbroker in that (theoretical) nail-biter of a primary season.

Thus, shifting norms about competitiveness and an ideological wrestling match will condition the 2020 elections, as an earlier presidential primary election or caucus provides no guarantee that either California or any state other than the first two— historically Iowa and New Hampshire—will be a decisive force in the national process.

Moreover, other critical economic and political factors, including national partisan tides, global economic waves, the array of candidates, and whether the current president remains in the mix, are more likely to be determinative.

While aspirants are trying to capitalize on the uncertainties created by Trump's election, Democratic political party elites are hunting feverishly for widely representative candidates who could create excitement and bridge existing intraparty divides.

Both Harris and Garcetti have the advantage of appealing to diverse Democratic constituencies in and outside California, and if either demonstrates the kind of leadership that unites those groups, California could be a launching pad for the Democratic Party's nominee.

Renée Bukovchik Van Vechten is an associate professor at the University of Redlands in southern California. Her text, California Politics: A Primer , is going into its fourth edition (CQ Press, 2016), and presages a more comprehensive, forthcoming textbook (The Logic of California Politics).

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.