The first thing that happens when I arrive at the Wilmington, Delaware, train station is that the newsstand cashier hands me counterfeit money as change when I buy an umbrella. Next, I walk outside and look for Sergeant Andrea Janvier. She's just over five feet tall, weighs about 100 pounds and has 18 years on the force, including 13 undercover in the drug unit. This fall she became Wilmington's public information officer, which means it's now her job to be nice to journalists like me. When I get into her cherry-red police car and tell her the location for an interview I have later that day, she lowers her Ray-Ban aviators, looks me in the eye and says, "I wouldn't go to that block without a gun."

During my four days in Wilmington last month, there were four shootings, all involving male victims between 17 and 19. None occurred while I was driving around with Janvier, 41, or when I did a ride-along with two cops. But as Janvier texted me the morning after I went home, "I just left a homicide scene, wouldn't it figure!" A few hours later, another text: "And a shooting just came in on Hilltop. It's usually always busy, it was just slow when you were here."

This is not unusual for a place that's routinely called one of the most dangerous small cities in America. This year, there have been 27 homicides in Wilmington, tying its record 27 murders in 2010, and 135 people have been shot. Twenty-two of them died. With a population of just over 71,000, Wilmington had a violent-crime rate of 1,625 per 100,000 people last year, according to the FBI's 2013 Uniform Crime Report (that crime rate measures murder and nonnegligent manslaughter, rape, robbery and aggravated assault). The national average was 368 per 100,000 people. Wilmington ranks third for violence among 450 cities of comparable size, behind the Michigan towns of Saginaw and Flint, according to a Wilmington News Journal report. For a city mired in violence, the most stunning fact of all may be that Wilmington just got its first homicide unit.

When you ask people in Wilmington about the root causes of the city's crime epidemic, their answers read like the devil's Christmas list: poverty, racism, lack of economic opportunities, drug and alcohol abuse, gun violence, high dropout rates, teenage pregnancy, stressed families and more. In the U.S., homicide is the leading cause of death for black men between 15 and 34. In Wilmington, where 58 percent of residents are African-American, crime and violence disproportionately affect poor black families, especially boys and young men. Exacerbating tensions between residents and law enforcement is the fact that the police department is 70 percent white and 21 percent black.

That disparity is reminiscent of Ferguson, Missouri, which was thrust into the national spotlight this summer when a white police officer shot and killed an unarmed black teen. Protests erupted across the city as police poured into the streets dressed in camouflage and armed with tanks, tear gas and military-grade weapons.

With a population of 21,000, Ferguson is much smaller than Wilmington, though it, too, has a predominantly black community (67 percent) and an almost entirely white police force (4 out of 53 commissioned police officers are black, according to The New York Times). As events unfolded in Ferguson, many news organizations called the city a "war zone." In Wilmington, where there is neither tear gas nor armored vehicles rolling down the streets, it's been that way for years, with nary a mention in the national press.

"This isn't Camden, New Jersey," says Cris Barrish, a News Journal investigative reporter who has chronicled Wilmington's escalating crime for more than two decades. "It still has a solid corporate and residential core, with ritzy and trendy areas…. The shootings have devastated parts of the city but are generally confined to four or five poor neighborhoods that circle downtown, and they've turned into war zones."

"You have a city with a deteriorating, almost destroyed infrastructure," says City Councilman Jea Street, who is executive director of the Hilltop Lutheran Neighborhood Center. "There are no jobs. Chrysler and GM are closing. The port, where, historically, young people without college educations could go get a job, that's no longer a viable option."

Mayor Dennis Williams, who took office in January 2013 (Wilmington had 154 shootings that year, according to the News Journal), blames the city's school system. "We have a 60 percent dropout rate. It should have never got to that point—and the state has been running the school districts here since 1975." Geography is another issue. Halfway between Philadelphia and Baltimore, Wilmington has become a way station for drug traffickers. When I-95 was built in the 1960s, it bisected established neighborhoods, pushing out "roughly 4,000 to 5,000 good, strong, working families," says City Council President Theopalis Gregory Sr. The highway made it easy for anyone looking to buy drugs to get off at the nearest exit. Today, some of Wilmington's most crime-ridden neighborhoods are in I-95's shadow, including Hilltop and Browntown.

This fall, the Department of Justice named Wilmington as one of six cities—along with Chicago; Detroit; Oakland and Richmond, California; and Camden, New Jersey—selected for the Violence Reduction Network. The program will support and train communities on how to develop long-term solutions for addressing violence and crime. The situation in Wilmington is so dire that, earlier this year, the state brought in the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to investigate the cycle of lethal violence and trauma in the city. The CDC is supposed to present its findings by the end of the year.

In the meantime, Wilmington's homicide unit—five detectives, one supervisor, one retired detective (paid by a grant) handling cold cases and two agents from the federal Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco, Firearms and Explosives—started combing through the year's unsolved murders. In mid-November, one month after assuming their new roles, they solved their first case, bringing this year's tally for cleared murder cases up to four.

Brother Lamotte X of the Wilmington Peace Keepers, which works to reduce crime and violence in the city, says he started campaigning for a homicide unit six years ago. "Mathematics don't lie," he says. "If I were a criminal and I wanted to kill somebody and I knew Wilmington didn't have a homicide unit, this would be one of the places I would come to do it."

'This block right here, it's terrible'

Wilmington is small—you can drive across it in about 10 minutes—and as Janvier chauffeurs me around, it becomes clear that there are actually two Wilmingtons. The nicest neighborhoods are snuggled in leafy middle- and upper-middle-class enclaves, where manicured lawns and stately homes and apartment buildings are enshrouded in a peaceful cocoon. The majority of all public U.S. corporations are incorporated here, including 65 percent of Fortune 500 companies. By the end of 2013, Delaware boasted more active business entities (over 1,052,000) than people (925,749).

The city is also the headquarters of DuPont, which grew from a gunpowder manufacturer in 1802 into one of the largest chemical companies in the world (it's behind Teflon, Kevlar and nylon, among other inventions)—and the nexus of a dynasty. The du Pont family is the 13th richest in the country, according toForbes, with 3,500 members and a $15 billion fortune. Drive 15 minutes outside the city center and you'll find sprawling landscapes studded with du Pont mansions, including Winterthur, a 1,000-acre preserve with a 175-room house; Longwood Gardens, which draws more than 1 million people each year; and Nemours Mansion, which has been called a "mini Versailles."

"Inside the same city, you have some of the poorest people and communities in the country—generations of black and brown families that have [been] in economic poverty," says Yasser Payne, a social psychologist and associate professor of Black American Studies at the University of Delaware. "There could be 20 to 25 people living in a two- or three-bedroom space.… I've never met more people getting shot or killed or hurt that I personally knew than in Wilmington. And I'm from Harlem!"

This other Wilmington is blighted with rundown, two-story brick row houses in high-crime neighborhoods like Hilltop, Eastside and Browntown. Some homes are vacant, their doors and windows boarded up. Many are rentals, which tends to attract a transient crowd, including drug dealers. Stoop after stoop, porch after porch, young black men sit and pass the time. During the day, women corral children in the park. When the sun goes down, many blocks are pitch-black. Very few porch lights are on.

"You have the world of big banking, the DuPont company and major law firms," says State Prosecutor Kathleen Jennings, who grew up in Wilmington and now leads the Delaware Department of Justice's Criminal Division. "Within blocks [of that], people literally cannot walk out their front doors." She tells the story of 5-year-old Jazmine Galan Grant, who went outside to get her scooter on a steamy evening in July 2013. As she stepped out on the curb, a bullet sliced through her left knee, severing an artery. Moments earlier, Jermaine Laster, 34, had been punched in the face and publicly humiliated by a local rival. In retaliation, he fired four gunshots down the block, missing his target but hitting Jazmine, turning her into the city's 85th shooting victim that year, according to The News Journal.

"That's what happens in our city," Jennings says. "Children can't go out and play."

Janvier turns down a street in Browntown. "This block right here, it's terrible," she says. "We've hit every one of these houses on search warrants. Shootings here. There were a couple victims in there. He's a drug dealer," she adds, pointing to a young man on the sidewalk. A moment later: "See what he just said?" she asks, pointing to a different guy crossing the street. (He had looked at our car and mouthed "Fuck you.")

When Williams, 61, ran for mayor, he touted his experience on the police force and in the state Legislature. He was a homegrown candidate from Wilmington's Riverside Housing projects, and he promised he wouldn't "hug thugs." Once in office, he divided the city into three sectors to enable police to exclusively patrol a given area, in hopes of solving more crimes and developing stronger relationships with residents. The plan calls for approximately 60 officers in each area. When I ask Janvier how many officers typically patrol these sectors, she replies, "Depends. Absolutely nowhere near 60, never was!"

The police force is authorized to have 320 officers, but it's short 27. A police academy, set to begin this fall to boost those numbers, was pushed back two months while the budget awaited approval.

Williams talks a lot about reaching young people through the city's recreational centers and scholarship, internship and jobs programs. "We had over 350 people in line," he says of a recent job fair. "That many men, wrapping all the way around the corner…that's horrific. It looked like the days of the Depression. A mayor can't do it all."

Not everyone is convinced the homicide unit can make a difference. "[The solution] is gonna be bigger and more longer term," Janvier says. "It has to start from the people themselves. The police can only police. They can't go to people's homes and raise their kids for them. The homicide unit really is, in my opinion, shuffling..." She pauses, then tries again: "Any detective can handle a homicide. Dedicating a unit to homicide..." Another pause.

She trails off, maybe because she can't find the right words, or because she knows exactly what she wants to say but, in her new role as public information officer, she can't.

City Councilman Street is more blunt: "The community asks for [the unit] because you've got grieving mothers who have no idea who killed their child. But it's going to take more than the Wilmington Police Department and the homicide unit to turn around the city."

'They all have guns'

"You might wanna buckle up," Corporal Cannon tells me. I'm sitting in the back seat of a black SWAT team Tahoe. Cannon, who's 32, and Corporal Geiser, 34, police the northeast sector of Wilmington, and they're letting me join them for a Saturday night ride-along. (Both requested only their last names be used.) Moments before, our car suddenly smelled as if it had been hot-boxed. The Cadillac in front of us is clearly the source of the marijuana smoke, Cannon says, and we could be seconds away from a car chase.

Geiser, who's driving, flashes the police lights, and the car pulls over. Inside are two black men in their mid- to late 20s. Geiser and Cannon handcuff and search them, then tell them to sit on the ground while they look up their information. The passenger, who's wearing a white T-shirt and Nike warm-ups, limps to the sidewalk. Cannon asks him what happened. Last year, the man says, he was shot seven times. "Who shot you?" Cannon says. The young man stares at the ground and shrugs his shoulders. "Were you locked up?" Another shrug.

I watch all of this from inside the Tahoe, which smells so much like marijuana that I wonder if I'm getting a contact high. Across the street, a few people gather on the corner to watch Geiser search the car. He finds a blunt and a bottle of prescription Tylenol with codeine. Despite this, he and Cannon let both men go. "They were honest. For us, honesty goes a long way," Geiser says.

Geiser has been on the job for eight years, Cannon for five. As a two-man car, they're often sent to "hot calls." I ask what that means. "A domestic violence complaint," says Cannon. "A shooting. Shots fired. Robberies."

They say they've seen an increase in broad daylight shootings over the past year and a half, and the incidents can erupt over just about anything. "A Facebook beef," says Geiser. "Or a beef from school. A family beef. 'You didn't give me my drug money you owed me.' Or, 'Hey, you looked at me the wrong way.'"

"They don't fistfight anymore," Cannon says. "We'll get called to fistfights—

"—Ten minutes later, someone's getting shot," Geiser says.

I ask them what it takes for a child in the worst parts of Wilmington to make it out.

"Parents who actually give a shit," says Cannon.

Nine boys, around middle school age, are hanging out on a street corner. Geiser pulls over, and Cannon rolls down his window.

"What's up, fellas? What you guys up to?"

"Going to the house," one says.

"All right, that would be a good idea. Goodnight."

Cannon rolls up his window.

"It's not the older ones we're worried about," Geiser says, pulling back into the street. "It's the young 14-, 15-year-olds. They all have guns."

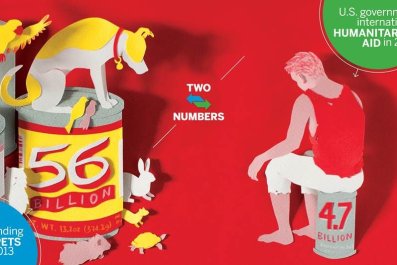

The U.S. has the highest gun ownership rate in the world. Between 1993 and 2011, gun violence accounted for about 70 percent of all homicides in the U.S., according to a special report from the Department of Justice. In 2010, black Americans were 55 percent of gun homicide victims but 13 percent of the population, according to a Pew report. Whites, on the other hand, represented 25 percent of victims and 65 percent of the population.

"It's a shame, because these kids only see one side of life," Geiser says. "You see a kid who's 4, and you drive by and he's doing this at you"—Geiser holds up one hand in the shape of a gun and clicks his finger on the imaginary trigger. "He could be playing, or it could be, 'My parents hate you.'"

'We're not Superman'

In October, a video surfaced of two Wilmington boys, both shirtless, fighting on a sidewalk while adults egged them on. The video went viral, but, as The News Journal reported, "on the block where this occurred people are keeping mum—at least with outsiders, which includes police. 'You don't live here,' one man said in explaining why no one on the block would talk publicly about the videos…. 'You're not going to be here when my windows are broken.'"

This code of silence is not unique to Wilmington, but it smothers the city's high-crime neighborhoods. Earlier this year, an Instagram account, "wilmington_snitches," posted the names of people reportedly cooperating with the police. (It has since been removed.) "It's a rare thing to have someone actually stand up in the middle of the block and tell us, 'This is what happened. This is who did it.' Because they live there," says Geiser. "When we leave, there's no telling what's gonna happen. Their house will get shot up, egged, vandalized."

"We've got this huge number of homicides, and only 15 percent have been solved. That's not the police's fault; it's the fact that nobody's talking," says Jennings. Improving trust and collaboration between police and residents is a top priority for Police Chief Bobby Cummings. Each week, the command staff walks the streets in an effort to get to know residents. "We'll get a lot of phone calls saying, 'Joe Smith did it,' and then they just hang up the phone," says Detective Randy Knoll, who's on the homicide unit. "You find yourself in a position where you know who did it and you can't arrest them. The community knows who did it, because they saw it. Then they watch him walk up and down the streets, and they're like, 'We called the police and said Joe Smith did it, and they didn't do anything about it.'"

"I can't stand when neighborhoods bitch, moan and complain that the cops aren't doing their job," Geiser says. "Well, you know what? We're not Superman. We can't be everywhere at the same time. We need the community to help us so we can help them."

'I'm this 18-year-old drug dealer'

Coley Harris, 41, represents the worst Wilmington can be and the best it can become. He grew up in a small row-house neighborhood wedged between two housing projects. His family went to church. By the time he was in middle school, he had turned to the streets. Harris staged his first robbery when he was 12. He started skipping school, smoking weed. He also watched older guys make serious money selling cocaine and heroin. "My dad's getting up at 4 a.m. to go to LaGuardia to pick up an executive [he was a chauffeur for DuPont], and my mother is going to cook for Head Start, and [what they made] didn't add up to what I was seeing here on these streets," he says.

Harris earned $200 to $500 a day working for a guy who trafficked coke from New York City. He dropped out of school in 1989, before finishing 11th grade. The war on drugs was in full effect, and by 1990, "my whole neighborhood was locked up," he recalls. "I was the oldest guy out there, with a crew of guys underneath me." By the time his son was born, in 1991, he was doing pills, snorting cocaine and drinking. "I'm this 18-year-old drug dealer, and I'm stressed out of my mind worrying about myself, my future, my child, and these kids looking up to me, because I'm the leader at this point."

In 1994, he shot and killed someone at a local barbecue, pleaded guilty to second-degree murder and concealing a deadly weapon and was sentenced to 16 years in prison. Inside, he started working with Project Aware, a program matching inmates with local at-risk youth. "We talked about family, self-esteem, how our inability to deal with our issues led us to hurt people," he says. "These dudes, they saved my life. Helping other people was a part of the process."

Harris was released in 2008, after serving 14 years. He was 34. His son was a stranger. His mother had a degenerative heart disease. He got a job at a hotel, making $9 an hour, and worked his way up to manager. He also started working at an adolescent substance abuse program. Today, he directs special programs for a national human services organization and works with youth and young adults in prison through a program called Victim's Voices Heard. He frequently speaks at schools, doing everything he can to steer young people away from a life of drugs and crime. Before his mother died last March, "she had the opportunity to see her son be the man she raised him to be—a father, husband, grandfather and a son to her, working in the community, doing everything I can to help my people," Harris says, calling this one of the most important moments in his life.

"There's a large population of disenfranchised, poor, misguided young boys in this city who are dangerous," Harris says. "I say that with empathy, because they didn't wake up like that. It's a direct result of neglect that came through the crack/cocaine/war on drugs era. It's a result of guys like me causing hurt and harm on other people.

"I'm not proud of my past, but I have to share it because there's a lot of young guys out here who believe life is over at a young age, just as I did. Listen, I was a shooter. When I was in the game, I was all the way in. But you never know the course your life will take. People or circumstances will stop you and spin you in totally different directions."

'Wolfie' at the Door

"If you take a petri dish and keep putting the same thing in it, you're going to keep growing the same thing," says Gregory, the City Council president. "How do we pour more positive opportunities into Wilmington to gain a sense of hope? That's a tough one."

David Kennedy, director of the Center for Crime Prevention and Control at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, argues that dangerous neighborhoods aren't by definition dangerous; they just have dangerous people living there. "If you identify all the gangs, groups and drug sets that drive violence, no matter [what city] you go to, the following is true: All those groups collectively will add up to under half of 1 percent of the city's population, and they'll be connected with at least half, closer to three-quarters of all homicide in the city," says Kennedy. (He is also co-chair of the National Network of Safe Communities, which collaborates with cities to reduce violence and community disorder.) Cities that have effectively reduced violence, he says, are doing so by focusing "on the small number of hot people and the small number of hot places where violence takes place."

A year after New York City implemented Operation Crew Cut, which targets street gangs, homicides among 13- to 21-year-olds declined 50 percent. Shootings and homicides overall declined 21 percent. The National Network has also brought its strategies to Chicago, New Orleans, Philadelphia and Baton Rouge, Louisiana, where the murder rates have dropped by about 20 percent. Last year, the Chicago Police Department made 7,000 fewer arrests. Since last year, shooting victims have decreased by almost half in Los Angeles.

Earlier this year, Delaware Attorney General Beau Biden created the Crime Strategies Unit to shut down drug dens, clean up graffiti, remove the stinking garbage that often piles up on the streets, fix faulty wiring and ensure houses are up to code. "If people know we're helping them with quality-of-life stuff, getting a streetlight fixed, clearing garbage—if we can do those little things, it builds trust and people start to believe that we care," says Jennings. "And we do care. Then they can feel safe talking to us."

The Wilmington HOPE Commission's Achievement Center, which opened its doors last April, mentors men returning home from prison. Delaware's recidivism rate is staggeringly high—nearly 70 percent of men released from jail will return within three years. In Wilmington, when these men return home, they find themselves in communities where 6 out of 10 men are either not participating in society or simply not around (i.e., incarcerated). "I don't think the threat of incarceration is big enough. Because [a lot of these men are] hopeless," says Charles Madden, executive director of the HOPE Commission. "Fundamentally, we've got to fix men and fatherhood."

"There are really bright people sitting in jail who chose the life of guns and drugs and violence because that's the life they grew up in," says Jennings. "You'll never have an 80 percent success rate, but if one-third or one-quarter of the people who come through [Madden's Achievement Center succeed], that's a lot of improvement."

Many of the grassroots organizations in Wilmington are staffed by people who came out of the same neighborhoods and blocks they're trying to help. The Wilmington Peace Keepers, for example, work with young men on street corners, schoolchildren and the homeless. "We go to places where it doesn't look or smell good, where no one else wants to go. We care for the people everyone has forgotten about," says Lamotte X.

Wilmington's Cure Violence project dispatches small teams to crime scenes, hospitals and the homes of victims' families to contain retaliation. "You need people who are credible in the community to go in and talk to the guys and try to buy time," says Darryl "Wolfie" Chambers. "We talk to young guys about the importance of letting authorities handle the investigation, and not go out and do anything irrational: 'What you feel now, you don't want other people to feel like that.'"

Wolfie, 45, has become an unofficial mayor around Wilmington's at-risk neighborhoods. He's a Ph.D. candidate in sociology at the University of Delaware and works as a graduate research assistant at the school's Center for Drug and Health Studies. He's often helping people find jobs and mentoring young boys and girls. In the eight minutes we stood together in front of the Wilmington Public Library, five people walked up and shook his hand. Two of them asked him for a few bucks to buy food.

Wolfie grew up in the Riverside projects. He was a high school all-American basketball player and earned an athletic scholarship to the University of California, Davis. After graduating in 1997, he was interested in going to graduate school (at that time for African-American studies), but he had no idea how to pay for it. He moved back home and started selling cocaine with a crew of five guys. "We were forced to build an economic structure in our community to take care of ourselves," he says. He ascended to the upper echelons of the drug trade before getting arrested in December 1997 on a charge of conspiracy with the intent to distribute and possession with the intent to distribute 150 kilos of cocaine.

He faced 35 years in prison but was locked up for just over 11 and was released in January 2009. That November, he became one of 15 Wilmington residents—all of them black, most ex-convicts—recruited by Payne to better understand life in two of the city's most crime-ridden neighborhoods. (The result, The People's Report, found that despite an overwhelming presence of physical violence and diminished opportunities, psychological and social well-being was thriving. Among the 520 young black men and women interviewed, 85 percent said they were "happy or very happy 'these days.'")

In the fall of 2011, two weeks after Wolfie started graduate school, his son—a 19-year-old honor student who had just enlisted in the Army—was gunned down. "I remember what his mother told me [at the hospital]: 'Don't let your son's death go in vain. The only way we can pull our people out of this muck is if you somehow start a revolution. Not a bloody revolution, but a political, economic, cultural, spiritual revolution. That boy shot your son because he didn't believe tomorrow offered better opportunities than today.'"

Those words forever changed the way Wolfie leads in his community. "I tell these guys now, 'Do you want the nice shoes and clothes? Remember that time I came back, about 20 years ago, and I said we gotta sell dope to get outta this?'" he explains. "I say, 'You trust me, right?' They say, 'Yeah.' I say, 'Now I need you to trust me that now we sell hope.'"