Shortly before Nazi Germany invaded Poland and launched World War II, Winston Churchill wrote an essay that asked "Are We Alone in the Universe?" For the next several years, as he led the United Kingdom through the war, it's unlikely he had much time to continue musing about the possibility of extraterrestrial life.

But when the great statesman and iconic leader—short and round-faced with a bowler hat often atop his balding crown—retired in 1955 after a second go as the British prime minister, he had the chance to turn his attention to painting as well as to writings he'd begun before the war, including his famous four-volume work, A History of the English-Speaking Peoples, and three essays on science that, it appears, have never been published.

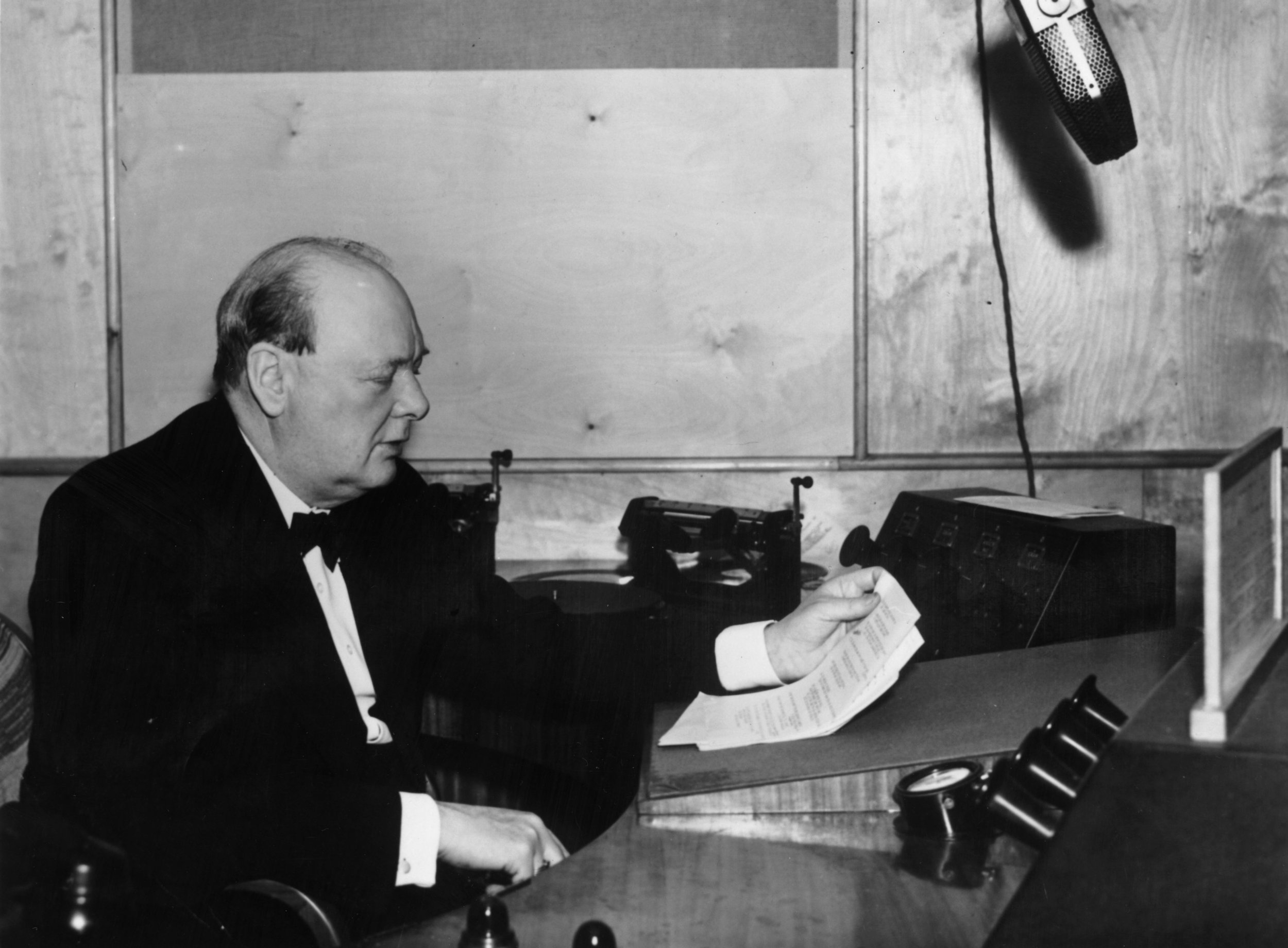

Mario Livio, an astrophysicist and best-selling author, wrote about the recently unearthed "Are We Alone in the Universe?" in a piece published Wednesday in the science journal Nature. Some of the original typewritten pages of Churchill's essay went up on display at the National Churchill Museum on Thursday afternoon.

"The thing that stunned me immediately is the title of the article," Livio tells Newsweek. "Because I just couldn't believe that Churchill would write an article on a topic like this. I knew that he had an interest in science, but most of what I knew was vis-à-vis the war effort."

Related: States, cities plan robust defense of climate science in Donald Trump era

But Churchill's interest in science was broader and deeper than weapons and warfare. Livio—whose next book Why? What Makes Us Curious (Simon & Schuster) is due out on July 11—was astounded not only by Churchill's curiosity, but also by his logic as he approached a question scientists are still trying to answer today. The full text of the essays cannot yet be made public because of copyright issues, but Livio describes "Are We Alone in the Universe?" in his Nature piece and compares it to current thinking. In pondering the possibility of life beyond Earth, Churchill tries to define life, lays out the necessary conditions (such as water) and describes what is now called the "habitable zone" or "Goldilocks zone"—the distance from a star that is neither too hot nor too cold to sustain life. He looks at candidates in our own solar system (Mars and Venus, in addition to Earth), discusses the need for an atmosphere and gravity and asks whether there might be planets around other stars that could harbor life.

"I find all of this truly amazing, coming from someone who is not a scientist," Livio says. Churchill didn't come up with anything entirely novel scientifically and there were places he was slightly off, Livio says. But unlike today, where a simple Google search could pull up a trove of sources, "there really wasn't that much information at the time," Livio says. "Most ordinary people, even the ones who were interested in the subject, were more fed by the science fiction literature than by the actual science. The fact that he knew as much as he knew was not usual."

Discovering 'Hidden' Essays

The essay, along with two others, recently resurfaced at the National Churchill Museum at Westminster College, a small liberal arts school in Fulton, Missouri. It's where, on March 5, 1946, Churchill stood with President Harry S. Truman and famously declared that "an iron curtain has descended across the continent." In the 1960s, the college decided to commemorate that significant visit with a library and museum devoted to Churchill.

"Since 1969 we've been a depository for Churchill papers, belongings, artifacts, paintings," says Timothy Riley, the director and chief curator of the museum. Riley first noticed the essays in the fall of 2014, as he was preparing an exhibit of Churchill's paintings. He went through four boxes donated to the museum in the 1980s by Wendy Reves after the death of her husband and Churchill's publisher, Emery Reves. Early in his retirement, Churchill would spend time at the Reves's villa in the south of France, painting and writing. The contents of the boxes were cataloged but no one looked closely at these documents until Riley picked them back up this past summer.

"People call them the lost essays. That's a bit much. They were just hidden for awhile," Riley says, explaining that there are also earlier versions of the essays from the 1930s at Churchill College in Cambridge, England. Riley says Churchill made a few updates to the essays while retired and on the Riviera in the 1950s. As far as he knows, they've never been published, examined by scientists or discussed in a forum as public as Nature.

"The prose just rings—it's very Churchillian. His command of language is very clear," Riley says. "His command of science and argument was also extremely acute." Riley was in awe, he says, but not entirely surprised. "The more you learn about his skills and his curiosity, his vision, his ability not to be afraid to make mistakes, his resilience, nothing can really be quite shocking," Riley says. "So when I saw these essays I kind of smiled and thought, 'There he goes again.'"

Riley decided to share the essays with scientists to "vouch for the veracity of Churchill's claims," he says. He gave Livio a copy of the 11-page "Are We Alone in the Universe?" when the astrophysicist was on campus this past September to give a talk, and passed the others on to Westminster faculty. He says we will likely hear more about them in the coming months.

The essay "Mysteries of the Body" is about human biology, Riley says, giving Newsweek a preview. "It talks about chromosomes and cells and how they divide and increase and multiply. How cells require water and liquid and oxygen." The third essay, "River of Life," is about evolution. Riley reads the opening over the phone: "Opinions vary about how our world came into being. Most scientists, however, appear to prefer the idea that together with other planets, it was formed from gases dragged out of the sun by the approach of some errant star." The essay goes on to discuss evolution. "It's something that a statesman and leader today, it's a topic they tend to avoid," Riley says, "or have very strong opinions about that have nothing to do with science."

'Heed Churchill's Example'

While Churchill displayed an impressive capacity and enthusiasm for scientific thinking, it was never divorced from his other areas of expertise. "Here is a person who witnessed the disastrous effects of the atomic bombs," Livio says. "He clearly realized that science can do great things, and he was a great advocate and was very passionate. But he also realized that science can do very bad things," he adds. "He wanted scientists not to be operating in a moral vacuum."

The other timely lesson here, both Livio and Riley emphasize, is the importance of science as a basis for decisions our leaders make. Livio reminds readers that Churchill was the first British prime minister to hire a science advisor, employing the physicist Frederick Lindemann. "Particularly given today's political landscape, elected leaders should heed Churchill's example: appoint permanent science advisers and make good use of them," he writes in Nature, and adds over the phone: "There are all these challenges to humanity, from climate change to diseases to famine that require input from science."

Riley agrees. "Anything we can do to share the importance of having good leaders be well-versed in science is a good thing," he says. "I'm hopeful we can add to that conversation. Or Churchill can help remind us of that."

If only American politicians read Nature. Some of them could certainly use a reminder. Or a revelation.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Stav is a general assignment staff writer for Newsweek. She received the Newswomen's Club of New York's 2016 Martha Coman Front ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.