Witness to Genocide: Looking Back at the Bosnian War

Over a trillion photos will be taken in 2015. When you separate out the fluffy kitty pictures and the Instagrams of people's lunches, and start to look at the photojournalism, there will still be millions of striking images vying for our attention.

It's a rare occurrence, but sometimes a powerful image reaches a worldwide audience and makes a strong impact. This happened earlier this year, with the famous photo of Aylan Kurdi, the Syrian Kurdish toddler whose drowned body washed ashore on a beach in Turkey in September and quickly brought the migrant crisis to international attention.

Sometimes photographs can rise above all else to become part of our daily conversation, if not stoke the discussion itself. When it goes viral, a photo, one hopes, could even push those in power to take action to make an impact on the ground.

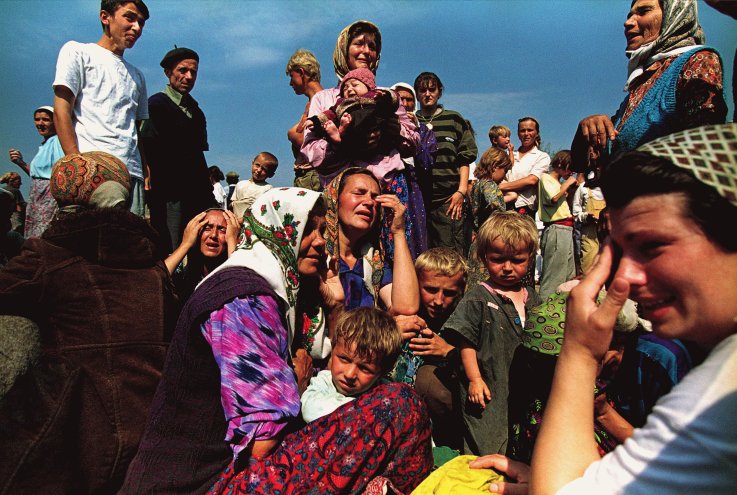

As the 20th anniversary of the end of the Bosnian War comes this year, I wonder what would have happened with my work from that period in today's digital age.

At the time, I was shooting photos primarily for magazines, including Newsweek, and my work could be seen by millions. But it was always limited to the printed page. It had something of an expiry date by the end of the week. I understood this, and strived continuously to have my work be part of the cultural and political conversations of the moment. I believe that if the greater public better understands conflicts happening globally, and if our political representatives are aware of and respond to the public's interest in such matters, then everyone would act in a more conscionable way.

As I documented three genocides over my career—Rwanda, Bosnia and Darfur—this notion was always perhaps more of a dream than a reality. But I persevered through three-and-a-half years of the Bosnian War believing that there would be a reaction.

Before the war officially began in 1992, I documented war crimes, including executions of civilians, which were later deemed to be some of the first civilian casualties of this conflict. That work was published, and I was confident that I had created meaningful visual evidence, as well as a glimpse into what was to come. But the reaction to those pictures was silence. The war began the following week, leading to thousands of deaths, millions displaced, and eventually another war in Kosovo.

I was deeply disappointed that there wasn't a stronger reaction to my photos, and as time went on, I began to realize that the world was paying less and less attention to what was happening on the ground in Southeast Europe—despite the fact that the civilian death toll rose and journalists became targets.

One day, while documenting the aftermath of a sniper attack, a civilian turned to me and said, "Why don't you leave? We don't want you here. You're not doing anything." Such sentiment became prevalent among some Bosnians, and many of my colleagues agreed with them, and soon decided to leave.

What was the point? It certainly did feel as though my work wasn't changing anything in the moment. But perhaps, counterintuitively, this became my motivation to continue creating documentation, a body of evidence that would hold people accountable for their actions—if not at that point, then someday.

The Bosnian War was also quite dangerous for journalists to cover. They were being killed or wounded at such a rate that armored vehicles and war training became the norm in order to work safely. I was taken prisoner while on assignment for Newsweek, and it was eventually required that the White House and other governments step in to negotiate for my release.

Some of the most common questions posed to me when I speak about my work are: Why do you continue to do this when war goes on with little abatement? Does your work make a difference? It's obvious to me that conflict and all that it reaps will not end. But in looking only for the absolute—in, say, the form of the end of a war—then there is no point in continuing this work. Photojournalism does not operate in absolutist terms. But I've found that if the work can affect even one person for the better, as small-scale as that may sound, then it is was worth the pursuit.

I look back at my photos from Bosnia and realize that they did go viral in a way—but in slow motion, compared to what happens with photos online today. The International War Crimes Tribunal in the Hague (ICTY) used many of my images in the trials of accused war criminals. The work is embedded in the collective memory of Bosnia, as it stands in the Bosnian National Historical Museum and Galerija 11/07/95 to remind people, both residents and visitors, what happened and what can happen.

The shorthand for this might be "never forget"—a phrase that originated in the wake of the Holocaust. And we should remember a prevailing response regarding the inaction during the Holocaust: "We didn't do anything because we didn't know." That response was no longer possible by the time of the Bosnian War, because this war happened live, broadcast in front of us. The war reporting produced showed the world, day in and day out, what was happening. In the end, we are all accountable, because our leaders act, or don't, on our behalves.

The goal with my work—my coverage of Bosnia, as well as many other places I have documented over the years—is to remind us all of our responsibilities as a civilization and of how intertwined we all are. If an image can impart a little of that sensibility on someone, then my work has succeeded.

Ron Haviv is a photojournalist with VII photo agency, who covered the dissolution of Yugoslavia from 1991-2000, and the Bosnian War from 1992-1996.