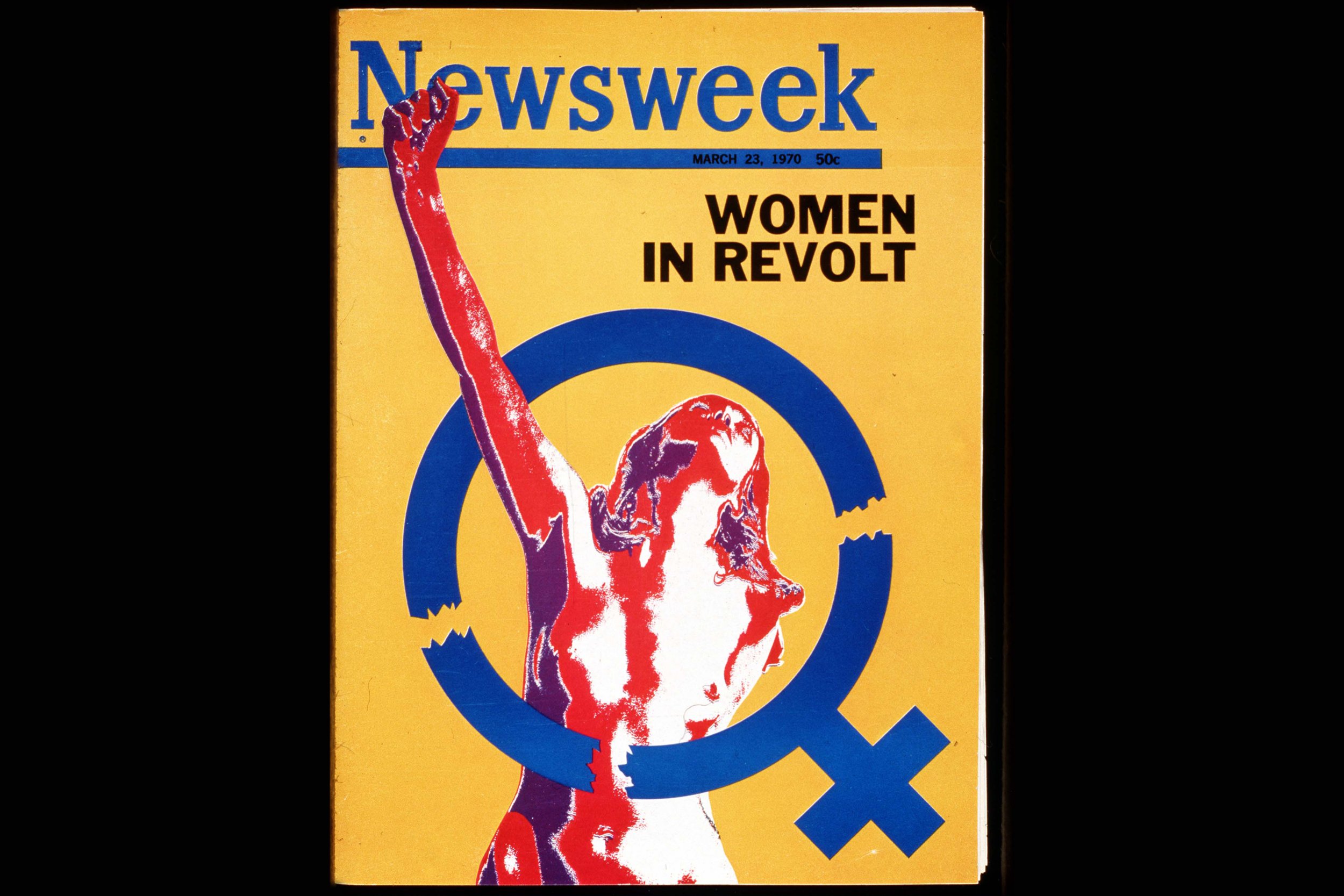

On a Monday morning in March 1970, the cover of a fresh issue of Newsweek featured a naked woman in red-tinged silhouette breaking through the symbol for the female sex. Black block letters against the bright yellow background read, "Women in Revolt." That same morning, 46 women on the magazine's staff held a press conference to announce they were suing Newsweek for gender discrimination, the result of a secret organizing effort that had been brewing in the office for months. Women at the Newsweek of the 1960s were mail girls, clippers, researchers and sometimes reporters, but almost never writers. Only one woman working at the magazine at the time had been promoted to junior writer: Lynn Povich. In 2012, she published The Good Girls Revolt: How the Women of Newsweek Sued their Bosses and Changed the Workplace, a book that inspired the fictionalized Amazon series Good Girls Revolt.

Related: "'Good Girls Revolt': The Legacy of a Newsweek Lawsuit"

To coincide with the release of the show's first season on Friday, Newsweek is republishing the cover story dated March 23, 1970 (though it came out on March 16), written by Helen Dudar, a female freelancer hired to do the story since the editors didn't believe any of the women in-house were up to the task.

Read it below.

"Women's Lib: The War on 'Sexism'"

In an age of social protest, the old cause of U.S. feminism has flared into new and angry life in the women's liberation movement. It is a phenomenon difficult to cover; most of the feminists won't even talk to male journalists, who are hard put in turn to tell the story with the kind of insight a woman can bring to it. For this week's coverage, Newsweek sought out Helen Dudar, a topflight journalist who is also a woman. Her report:

After a while, when friends asked what I was working on these days, I would say, "Oh, this and that," and then hurriedly ask about the children. One more curdled dinner, one more snarling exchange between a man and a woman whose life together had always seemed so friendly became an insupportable prospect. At the beginning, even before anyone asked, I often broached the subject myself. If the couple knew what the women's liberation movement was, there would be an immediate argument, he looking wounded and murmuring between clenched teeth, "But honey, whadya mean you're thinking of joining—don't you feel free?" and she responding with soothing persistence, "Yes, yes, but I just have this feeling I should make an existential commitment." If they had not yet heard of women's liberation, I would explain, and then an argument would follow. Sometimes it was he who might ask whether valid questions were not being raised, while she, facing attack on her roles as mother, wife, keeper of the hearth, rose in perplexed anger at alien ideas that suggested she had invested her entire life in triviality.

So I discovered almost at once how swiftly the subject assaults the emotions. No one is immune. Suffragettes were those funny ladies in rickety newsreels who tied themselves to lampposts to win the vote. America's New Feminist is the neighbor's college-educated daughter coolly announcing she does not intend to marry. She is Judy Stein, 16, founder of the women's lib at New York's High School of Music and Art, paying her way on dates. ("Otherwise, it's like the guy is renting you for the evening.") She is also Ti-Grace Atkinson, long past the stage of denouncing marriage and motherhood, now writing elegant analyses of the need to give up sex and love, both, in her view, fundamental male means of enslaving females. Finally, the New Feminists are thousands of women with lovers, husbands and children—or expectations of having a few of each—talking about changes in social attitudes and customs that will allow every female to function as a separate and equal person.

Toy: That, of course, is not how the American woman sees herself now. She is, in the labored rhetoric of the movement, a "sexual object," born to be a man's toy, limited and defined by her sexual role rather than open to the unbounded human possibilities held out to men—or at least, to some men. Usually she is not yet out of diapers when she learns that girls play with baby dolls, boys build things. If she is smart, grownups begin early to warn her against being too smart. "When you turn out to be a mathematical genius," reported a young woman at Columbia University, "your mother is the one who says 'put on some lipstick and get a boy friend.'"

She becomes a secretary, a teacher, a nurse, and only occasionally a doctor, a lawyer, or a chief of anything. Whether she works in a factory or makes it in one of the elite professions, she earns less than men and has fewer prospects for promotion, no matter how superior she may be; women, by definition, are less superior than men. When she has children, she is chained to their needs for most of the years of her vigor and youth. She is Fred's wife and Jenny's mother and, beyond, that, she may realize one late day, she has no other identity.

Image: The makers and sellers of consumer items pamper her with goods and attention concentrated on reinforcing a sexual image. "We're basically invisible," says Jo Freeman, a Chicago political scientist. "I look at the TV screen and the ads, and there is this person who's either sexy or shrill, and that's what's called a woman. I'm not that person, nor is any one of my friends. But you never see any of us." Nanette Rainone, who produces what may be the only female-liberation radio program in the country for WBAI in New York, says that, finally, to be a woman is to be nothing. "The guy on the assembly line doesn't want to be a woman. It's not that the work at home is worse than at the factory. It's that he realizes it's nothingness, total nothingness."

What has come racing along to fill the vacuum is the women's liberation movement, a very loose designation for a multiplicity of small groups led by a multiplicity of women who decline to call themselves leaders. The membership is mostly young (under 30), mostly middle class in origin, mostly radical and almost exclusively white, black women having chosen to remain within the confines of the civil-rights struggle. Because many of its founders came out of the New Left with its violent distrust for hierarchy, groups tend to be localized, unstructured and unconnected, although they all make common cause on such immediate issues as abortion-law repeal and establishment of day-care centers for children.

Women's lib has sprouted a growing periodical literature which includes No More Fun and Games, Tooth and Nail and Aphra (named for Aphra Behn, the first English female novelist); it also boasts a feminist repertory-theater group; at least one dramatist—Myrna Lamb, whose play "The Mod Donna" is due to be produced by the New York Shakespeare Theater next month—and it has inspired at least a dozen new books, finished or in the writing stage. But estimating the movement's membership is a frail numbers game. One regular lecturer on the movement told me with surprised pride, that at least 10,000 women must be in women's lib. Another insisted that 500,000 was a conservative estimate. Most fair-size cities have one or more groups and so do most campuses. The movement is flourishing in Canada, England and the Netherlands, where Provo-like "Crazy Mina" groups have augmented the U.S. program with demands for female public urinals and a twenty-hour workweek that would enable husbands and wives to share the burdens of child-rearing.

Growth: Of a certainty, the new feminist wave is building. Marlene Dixon, a radical sociologist whose failure to win reappointment at the University of Chicago set off take-over protests fourteen months ago, is now at McGill University, and almost every weekend she flies somewhere in the U.S. in the interests of the movement. "For five months after I left Chicago," she says, "I worked full time organizing groups. In the late spring of last year, I went down to Iowa City and met with a group of ten women consisting of two students and eight faculty wives—an unlikely group to start a movement. Recently, I was back there for a conference they had organized, and they had 400 women. In the last few months, I've been to ten conferences, mostly in the Midwest, and none was under 300."

Plunging into the movement can mean a new life style. Some women give up make-up; a lot of them fret over whether to give up depilation in favor of furry legs. A few of them are a bouncy-looking lot, having given up diets and foundation garments. And virtually all those in the movement light their own cigarettes and open their own doors. "Chivalry is a cheap price to pay for power," one lib leader commented. In any event, the small masculine niceties now appear to liberationists as extensions of a stifling tradition that overprotects woman and keeps her in her "place."

For a newcomer to women's lib, the truly jolting experience is the first encounter with the anger that liberationists feel toward men. It bristles through the literature of the movement and it explodes into conversation in great hot blasts of doctrinaire invective. "There is no such thing as love between an adult male and a child," a feisty working-class liberationist with four grown daughters told me. "Between mother and infant, there is a bond. But in the father there is no such thing as affection, love or any human emotion, other than the sense of power and property."

This kind of hostility, one young ideologue insisted, is healthy—"a gut reaction to a real situation" and without any of the guilts stirred by psychoanalysis. But it is also gravely infectious. I came to this story with a smug certainty of my ability to keep a respectable distance between me and any subject I reported on. The complacency shriveled and died the afternoon I found myself offering a string of fearful obscenities to a stunned male colleague who had "only" made a casual remark along the lines of "just-like-a-woman." "How do you control the hostility?" I kept asking, because in the beginning it came nervously close to interfering with normal routine. "I've been absolutely overwhelmed by feelings of hostility that scare the hell out of me," a 24-year-old nursery-school teacher told me in San Francisco. But, she went on, much of the anger was "victim's rage" and it could be alleviated through constructive women's liberation activity. She also found it helped to stay away from men.

No Men: That is the solution recommended for all militants by Ti-Grace Atkinson, who is part of a hard-line New York group, The Feminists. Ti-Grace will no longer appear with a man except as a matter of "class confrontation"—a TV debate, a public platform—and she says that total separation works wonders since it dissolves ambivalence, and it is ambivalence that fosters rage.

Sardonically, she observes, "The basic issue is consistency between belief and acts. Of course, you know that every woman in the movement is married to the single male feminist existing. That's why we're funny. Contradiction is the heart of comedy. A woman saying men are the enemy with a boy friend sitting next to her is both humiliating and tragic."

Ridicule has pursued the feminist down the corridors of time like some satanic practical joker; it is almost a relief when the hilarity turns to anger. "My male friends used to find us funny," said one activist. "I guess they've started taking us seriously; now they get mad." In the movement, there is a fidgety expectation of eventual backlash, supported even now by an occasional burst of male violence. Last December, when the Chicago chapter of the National Organization for Women (NOW) demonstrated against a traditional men-only lunch place, a large and angry man pushed a small, bespectacled matron in the face. NOW filed a complaint of assault. "In court," said Mary Jean Collins-Robson, the chapter president, "the prosecutor laughed, the public defender laughed and the judge, who happened to be a black man, laughed and threw the case out."

Among the many things that incite movement women to fury are the liberties men take in addressing them on the street—whistles, "Hey, honey," greetings, obscene entreaties. Casual annoyances to the unenlightened, this masculine custom becomes, in the heightened atmosphere of women's liberation, an enraging symbol of male supremacy reflecting man's expectation of female passivity and, more important, his knowledge of her vulnerability. "We will not be leered at, smirked at, whistled at by men enjoying their private fantasies of rape and dismemberment," announced a writer in a Boston lib publication. "WATCH OUT. MAYBE YOU'LL FINALLY MEET A REAL CASTRATING FEMALE."

Karate: Her point was part of a plea for the study of karate, a fashion that inspires men to helpless ho-ho-ho's. The lib view is that most girls, discouraged from developing their muscles, grow up soft, weak and without any defense reflexes to speak of. A little karate can go a long way in a woman's life, according to Robin Morgan, a poet, a wife, a mother and the designer of the women's movement's signet—a clenched fist within the circle of the biological symbol for female. "Walking alone at night on the street," she says, "there is always that feeling of muted terror—and utter panic if you think someone is following you. Knowing a small bit of karate is really remarkable—you may be afraid, but you don't feel impotent."

In the new feminist doctrine, karate is not merely a physical or psychological weapon. It is also political, an idea that makes sense if you agree that rape is a political act. And rape becomes political if you accept the premise that women are a class, probably the original oppressed class of human history; that their oppression is a conscious expression of the male need to dominate; and that a sexual attack is a display of power allowed by a "sexist" society.

Sexist is the women's lib term for male supremacist and an offense to the language we will have to learn to live with. Its kinship with racist is obvious and probably inevitable in a movement that draws much of its rhetoric and spirit from the civil-rights revolution and that, like America's first feminist wave, evolved out of the effort to liberate blacks.

Suffrage: Born out of the abolitionist struggle, nineteenth-century feminism exhausted itself in 72 years of painful effort during which a wide-ranging effort to change the status of women was finally narrowed down to a compromise drive for suffrage. The vote for women arrived in 1920, along with a few other reforms that went part way toward converting women from property to people. But the ballot "means nothing at all if you are not represented in a representative democracy," writes Kate Millett, a Barnard College teacher and leading theoretician of today's movement.

The modern feminist movement has grown along two parallel lines. The first derived from Betty Friedan's "The Feminine Mystique," published in 1963. Reflecting on the post-World War II stress on the "creativity" of homemaking, Mrs. Friedan told women that a male-dominated, consumer-oriented society had conned them into producing more children than their mothers had, into giving up career hopes, into lives deadened by trivia and, finally, into a mystified struggle with the emptiness and malaise that came upon them in middle age.

"The Feminine Mystique" spawned NOW, headed by Mrs. Friedan since its inception in 1966. (She will resign as president this month to return to writing.) NOW, which is also open to me, currently has about 35 chapters. Early announcements described it as the NAACP of women's rights and, in fact, NOW is reformist in approach, attacking job inequalities and other injustices through court action and legislative lobbying. In New York, it is starting a drive to bring more women into public office.

The elective process has scant interest, however, for the members of women's liberation—the second and more radical wing of today's feminist movement. Around the time the Friedan book appeared, scores of young women in the civil-rights movement and in the infant New Left were learning what it was to have a college education and to be offered a porter's job. Their contributions seldom were allowed to go beyond sweeping floors, making coffee, typing stencils and bedding down. "The New Left has been a hellhole for women," says a Berkeley veteran. "It's the most destructive environment sexually I've ever encountered, going as far as Norman Mailer's anti-birth-control posture. You know: I don't want my chicks using pills—that demolishes my immortal sperm."

Hoots: As a result of all this, female caucuses congealed in civil-rights and student groups, struggling against "hoots, laughter and obscenities" to persuade male revolutionaries that American society and its men oppressed women. The atmosphere was so oppressive, however, that the women took to meeting separately. And finally, in mid-1967, starting in Chicago, they began breaking away from the parent organizations entirely.

Since then, women's lib groups have multiplied like freaked-out amebas, sometimes under sardonic titles, often nameless. San Francisco has Sisters of Lilith, the Gallstones and SALT (Sisters All Learning Together). Several cities have WITCH (Women's International Terrorist Conspiracy from Hell), which produces mocking guerrilla theater on such pillars of the system as Wall Street and claims ancestral feminist kinship with the witches of old. Boston has Bread and Roses, a name derived from an early women's mill strike in Massachusetts. New York is a splinter-group paradise—WITCH, Redstockings, Media Women, The Feminists, the newborn Radical Feminists, and a host of special-interest caucuses in such unexpected places as City Hall.

Trust: The differences among women's lib groups are often Jesuitical, but they do suggest the range of possibilities open to women in rebellion. Nomenclature notwithstanding, The Feminists, who take a hard line against marriage, are perhaps more radical than the Radical Feminists. But the Radical Feminists, too young to have been active in much of anything yet, may wind up more active politically than the Feminists; the Radicals see themselves eventually dealing with issues in "pragmatic terms." the Feminists, in fact, are less concerned with personal self-discovery than with analysis of the social institutions that oppress women. By contrast, self-discovery is a prime goal for the members of the Redstockings which has been defined as neither revolutionary nor reformist but committed to "what is good for women." As for WITCH, whose members insist on anonymity, it seems to be open to all possibilities—"theater, revolution, magic, terror, garlic, flowers, spells."

Often a women's lib organization is simply described as "my little rap group," and that is substantially what the movement has been about up to now—five to fifteen women meeting weekly in an exchange of ideas and experiences. In these "consciousness-raising" sessions, rage spills out, anxieties are dissected, and women learn how similar are their lives and problems. They also learn to like other women. "For the first time, I've begun to trust women," a book editor told me. "I look at them more closely. Even a woman I find obnoxious, I can see as a person, not as a stereotype."

Breakups: But women's lib members sometimes stereotype men. "Your husband is a writer, too?" a woman asked me. "Isn't he jealous?" I said no; she looked skeptical. Participation in the movement, in fact, can be hard on pairings. Marriages and settled affairs have come apart over the woman's newly developed anger or the man's newfound prejudices.

Yet a lot of women I met were married to men they felt were relatively free of the burdens of "machismo"; in these cases, maleness did not stand in the way of sharing the drudgery of tending house or babies. And a few couples manage exceptional partnerships. In New York, I met a husband and wife who both have part-time jobs so that each can spend half the day with their infant son. In Berkeley, I heard of a woman editor with a "house-husband." She went out each day to a job she liked; he cheerfully gave up one he hated to stay home with the baby. But these are essentially private solutions. For all its talk of abolishing marriage and motherhood, much of the movement is focused on the liberating possibilities of a network of child-care centers staffed by men and women who will take drudgery out of child-rearing.

Nor is this simply a utopian illusion. "I would like a revolution," New York reporter Lindsy Van Gelder told me. "But realistically, I suppose I would settle for what Sweden has. "Which is a fair beginning. For as the result of an intense debate during the past decade, Sweden is now undergoing a wave of feminist reform. Fourteen per cent of its parliamentary seats and two of its Cabinet ministries are held by women. Women run cranes, cabs and buses; fathers must support children, but divorced wives are expected to pay their own way. There are compulsory co-educational classes in metalwork, sewing and child care; a new tax structure virtually forces wives to go to work; a start has been made on daycare centers and, this year, a government-ordered revision of textbooks is expected to begin eliminating stereotyped images of both sexes.

Sex: But Swedish-style reforms, though admired in the movement, are hardly a subject of active debate. The recurrent preoccupation of rap sessions is sex: the disappointments of sex, the failures of orgasm, the ineptitudes of men. The discussions seem endless, and the obsessive literature the subject has produced fuels an obsessive male view—what I have to call the Big Bang theory of women's liberation. Men seemed transfixed by the notion that all any of these women need is really swell copulation. Few men pause to ask whether causing the earth to shake for a woman each night will obliterate her boredom, frustration and sense of injustice each day. And they are very puzzled by her complaint that the predominant male view of women is sexual.

Lesbian-baiting is another favorite masculine exercise, and it has produced some interesting reactions among liberationists, including sober debates over whether lesbianism is a viable alternative to heterosexuality. "A woman who doesn't mind any other insult—'go home and take a bath,' 'what you need is a good screw,' 'dirty, Communist pinko'—will dissolve in tears because someone calls her a dyke," says Robin Morgan. So, women's lib has started asking why women react that way, to welcome lesbians into the movement as "our sisters," and to consider the idea of homosexuality as a means of population control and a path to equality.

Between the marriage abolitionists and the lesbian flirters falls a kind of moderate radicalism. Shulamith Firestone, a founder of the New York movement, and author of an upcoming theoretical work called "The Dialectic of Sex," says most women prefer sex with men and should have it, but without allowing themselves to become dependent or to be used as "doormats." Anne Koedt, another New York pioneer, is cautious about advising anybody to do anything. "You have to be honest with yourself," she says, "to take each step when it's real to you. We have just so much tolerance for change."

As I sat with many of the women I have discussed here, I was struck by how distorting the printed word can be. On paper, most of them have sounded cold, remote, surly, tough and sometimes a bit daft. On encounter, they usually turned out to be friendly, helpful and attractive. Meeting the more eccentric theoreticians, I found myself remembering that today's fanatics are sometimes tomorrow's prophets. Among the women I interviewed were careerists and intellectual hustlers; few of them, moreover could resist sly put-downs of a competing group. Yet the total impact has been a quality of uncorrupted tenderness, a sense of unsentimentalized "sisterhood" threaded throughout the movement.

Free: It was refreshing to find women who weren't desperate to land a husband. But much of the talk of liberation from dependency seemed delusive. Who is truly independent, except the man or woman with no personal relationships at all? The newly free feminist, I would guess, draws support from her group—another form of dependency. Also, few of the women I met would allow that life itself is unfair. Most of them cherished an apocalyptic conviction that a society that assumed the drudgery of child-rearing would free women. Free them for what? For the jobs that millions of men now have and hate?

But millions of women do not even have the choice, and options are really what this revolt is about. I was startled to discover that the name of Dr. Benjamin Spock, which suggests sound baby-rearing and impassioned peace-seeking to me, evokes hisses at lib meetings because the movement associates him with keeping woman in her place. Always opposed to the working mother, Spock has taken to speaking unkindly these days about the aspirations of the educated girl. "Spock wasn't born to be a pediatrician," Nanette Rainone told a Columbia liberation teach-in last month. "He made a choice. Women are told it is their destiny to be mothers—the way to fulfillment. And if they want an abortion, fulfillment is forced on them."

Split: The way to fulfillment is spiky. After two years of talking, of self-discovery, no one has learned how to confront the issues. For the moment, the women's lib movement is split by competing ideologies—between pure feminists who want to go it alone and political feminists convinced they must work with other radical groups to bust the system. And there is a general fragmentation that suggests a more serious impediment. "I have a sense of an enormous kind of movement that isn't really organized," says Leslye Russell of Berkeley. She worries that it is "doomed to being a fad" unless it pulls itself together. "To be effective, there must be some kind of mass membership and some kind of structure. The point isn't structure, but structure that must be democratic."

Although not everyone agrees more organization is the solution, there are some signs of change in that direction. Most of Chicago's groups have just united under the Women's Liberation Union, with a citywide steering committee. New York's Radical Feminists, conceived by Shuli Firestone and Anne Koedt, is setting up small groups, each responsible for organizing a "brigade," each brigade to be represented by rotating delegates on a citywide coordinating body—the whole aimed at a mass-based movement with replicas in other cities.

No Power: There is, of course, territory hardly touched by the new spirit. Roxanne Dunbar, one of the movement's most important theoreticians, has just left her Boston group to try to organize Southern women, the women she knows best. She is looking to build something, but in common with most of the sisterhood has an aversion to defining it in terms of power. Power is what men have. "You can't overcome power with liberation power," she says, "because it would be a monster. What we want to do is build groups that isolate power." No sensible person, she suggests, wants to see women "liberated into the social role of men." She is out to destroy both roles.

The prospect fills me with joy, and—let me add at once—that is a world away from the position I held a few months ago. I have spent years rejecting feminists without bothering to look too closely at their charges. Stridency numbs me, and, in common with a lot of people, it has always been easy to dismiss substance out of dislike for style. When you think about it, though, my distaste for the presentation was silly: who listens to complaints in pianissimo anyway?

Pride: About the time I came to this project, I had heard just enough to peel away the hostility, leaving me in a state of ambivalence. We all thought—the men who run this magazine and I—ambivalence, Wow! What a dandy state of mind for writing a piece on the women's lib movement. Well, I suppose the ambivalence lasted through the first 57½ minutes of my first interview. Halfway through an initial talk with Lindsy Van Gelder, a friend and colleague, she said almost as a footnote that a lot of women who felt established in male-dominated fields resented the liberation movement because their solitude gave them a sense of superiority.

I came home that night with the first of many anxiety-produced pains in the stomach and head. Superiority is precisely what I had felt and enjoyed, and it was going to be hard to give it up. That was an important discovery. One of the rare and real rewards of reporting is learning about yourself. Grateful though I am for the education, it hasn't done much for the mental stress. Women's lib questions everything; and while intellectually I approve of that, emotionally I am unstrung by a lot of it.

Never mind. The ambivalence is gone; the distance is gone. What is left is a sense of pride and kinship with all those women who have been asking all the hard questions. I thank them and so, I think, will a lot of other women.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.