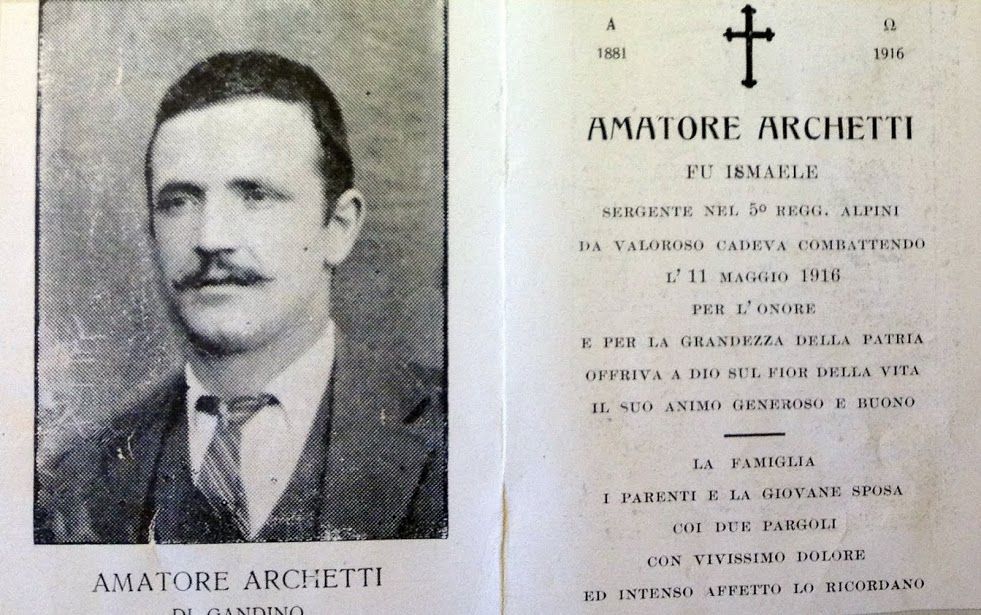

It's a cold May morning at 6,000 feet in the Eastern Alps. Knee-deep in icy snow just below the summit of Mount Čukla, lost in the fog and clinging to wet rocks, I am standing on the site of one of the most brutal battles of World War I, 100 years after the war to end all wars began. My great-grandfather never made it this far up the mountain. Sergeant Amatore Archetti of the Italian Army's 5th Alpine Regiment was killed in action just south of here on May 11, 1916, the day his comrades took the summit back from the Austrians.

He was one of the 10 million soldiers who died in the war that began a century ago, on July 28, 1914. His brother-in-law, artillery Corporal Giovanni Maria Rottigni, died the following October, hit by an Austrian shell in a trench 50 miles to the south.

On the slopes of Čukla in what is now the tidy, peaceful nation of Slovenia, World War I seems still close enough to touch. The valley of the impossibly blue Soča River is now a haven for kayakers and winter sports, but fields and backyards still regurgitate shells, helmets, bullet clips. The river's very name brings dread to Italians: Isonzo, a word as fraught as Iwo Jima to American ears, or Verdun to the French. The 12 Battles of the Isonzo, fought here between 1915 and 1917, killed a majority of the 600,000 Italian troops lost in the war.

Now, a century later, I am here chasing their memory, and the remains of a history that Italy has largely rejected. The country hasn't quite come to grips with the legacy of the only major war it ever won. Hijacked by fascism and turned into an avatar of aggressive nationalism—a young Benito Mussolini fought on this very mountain, noting the bitter cold of Čukla prominently in his diary—the Great War was an unmentionable for decades. It was the deadliest Italian war, killing twice the number of soldiers that World War II did, yet its nationalistic overtones made it into a near-taboo subject to many Italians rather than a hallowed memory.

My family rarely talked about the great-grandfather who died in that war. His children—my grandmother and great-uncle—never made it to the war memorial where he rests, never even knew where it was, until decades later, when my father tracked it down. My great-grandmother Bettina, who had lost a husband as well as a brother, died before I was old enough to ask her about those years.

Yet today, spurred by the hundredth anniversary, talk of La Grande Guerra is finally permissible. "The memory is returning, in a major way," says Paolo Rumiz, an Italian author and journalist who has written extensively about the Great War. His grandfather fought on the other side, with the Austrians—not an uncommon occurrence in this part of the world, where families changed nationalities more than once as Italy, Austria and Yugoslavia grabbed chunks of this corner of Europe.

The Italian language has an expression, it was a Caporetto, to indicate a devastating defeat. Caporetto is a hamlet here, just south of Čukla, where the Italian army was routed in late 1917 before regrouping to win the war one year later. Now a Slovenian town called Kobarid, it houses an Italian war memorial with the remains of 7,000 soldiers, great-grandfather Amatore among them.

His letters home, collected in an album by the son he never met, describe the landscape perfectly. The fortifications where he took shelter from Austrian shells are still there, carved into the mountain. "We build trenches at night and by day we rest," he wrote, "in some cave protected from the enemy artillery." Damp and cold in late May, the caves must have been torturous in winter.

His grandson Franco, my father Silvio and I tread carefully up the mountain. We are all experienced climbers, but the barbed wire that stopped assaults a century ago is still there, rusted but just as dangerous to distracted hikers. Tin cans that long ago held field rations rest among the stones.

Overhead, circling vultures remind the visitor that death once ruled this mountain. Far below in the town of Bovec, its tools are everywhere, below the pretty surface of an idyllic resort. Our innkeeper shows us the exploded shells and intact bullet clips he's found in his garden. His neighbor, he says, had to call in the army when he found seven live grenades while digging up his yard.

"History, here, is geology," Rumiz says.

No description of what was really happening on the front lines in 1916 would have made it past the army's censors, but my great-grandfather tried. "Life is indescribable," he wrote in March, in a letter that somehow slipped through. "We are just a few meters from the enemy trenches above us. We await anxiously the order to attack, at any moment … and currently we are taking losses with no progress."

He was 35, an old man compared to most of his fellow soldiers. But he could ski, and therefore was drafted as an instructor for the mountain troops, the Alpini. He wrote his last letter, dated May 5, 1916, to his brother Giobbe: "I hope we'll get replaced in a few days, so we can have a few days' rest and get rid of the insects tormenting us."

It was, literally, an uphill fight. On the Isonzo front from 1915 to the end—Italy entered the war one year after the other big European nations—the Italians took twice as many casualties as the Austrians. "It was a nightmare," says Rumiz. "You were constantly climbing, with the dreadful echo of the artillery guns" reverberating from the steep mountainsides.

Europe has come a long way since the fighting on Čukla. It's a peaceful union of 500 million people that doesn't even demand to see passports at its borders; on the frontier where our ancestors fought ferociously for every inch of ground, we breezed through from Italy with nary a wave from the Slovenian guards.

That border used to be the Cold War's front line, too: Yugoslav Communists east of the barbed wire, Italy and NATO west, on a frontier that had seen war since Attila the Hun came this way with his sights on Rome. Driving down the Isonzo to the Adriatic Sea today, one gets the feeling that the unrest brewing east of the river could make its way to this border easily.

The headlines in the Slovenian and Italian newspapers talked about the upcoming elections for the European Union's parliament, in which bellicose right-wing xenophobes would do well across the continent. The civil war in Ukraine echoes loudly here: It's happening just across the plains of central Europe, near the old border of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that died with the Great War. "We are sleepwalking, like they were in 1914. They just don't understand," says Rumiz of Europe's current leaders, when we meet in a coffee shop in Trieste, the empire's port city. Italy captured it in 1918, lost it again after World War II, and gained it back in 1954. Few other cities bear such powerful witness to the madness of Europe's 20th century.

"The Balkans, Ukraine, North Africa, Catalonia… These conflicts are on the same fault lines of 1914," says Rumiz, reeling off a list of everything that's going wrong in and around the prosperous, but crisis-plagued, area. Yet the leadership in Brussels is ignoring the war's centenary "because it's afraid. They know they aren't really united, but rather susceptible nations."

Rumiz has written extensively on the wars next door to Trieste, in the former Yugoslavia. The bones of the dead he saw at Srebrenica in Bosnia remind him, he says, of the Italian and Austrian soldiers' bones that sometimes still surface near here. He is just back from traveling along the front lines of World War I, chronicling its legacy for Italian newspaper la Repubblica, and the message he took back is not encouraging: "Peace is not written into our DNA."

But in the quiet of a spring afternoon, finding my great-grandfather's name etched in the stone of the Kobarid memorial did not evoke warlike feelings. At the entrance to the mausoleum, a sign placed by the Slovenians, themselves a nation produced by civil war, featured an elegant logo with a stylized white dove. Signs like it appear all along the trails once trod by soldiers' boots. The stories they tell are impossibly bloody, but the Slovenian name they bear says something else: Pot miru, the path of peace.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.