This article first appeared on the Hoover Institution site.

A public event with the eminent scientist and rationalist Richard Dawkins was cancelled late last year by a Berkeley radio station.

A spokesman for the station said that Dawkins had "said things that I know have hurt people," a misleading allusion to the atheist Dawkins's forthright criticism of Islam which, along with all religions, he regards as irrational.

The station's general manager declared: "We believe that it is our free speech right not to participate with anyone who uses hateful or hurtful language against a community that is already under attack."

This is only one of the more recent in a string of dis-invitations of public figures on North American college campuses. Following the violence at Charlottesville in August last year, free speech has become a thornier subject. But no matter how evil, all speech is protected by the Constitution, even that of Antifa and white nationalists.

The cliché that sunlight is the best disinfectant holds true. By allowing these groups to express themselves out in the open, we can clearly see what they are saying, and, if we disagree, counter it.

I am among those who have been "de-platformed" for speaking critically about the political and ideological aspects of Islam that are not compatible with American values and human rights. The usual justification for disinviting us is that speaking critically of Islam is "hate speech" that is "hurtful" to Muslims.

However, this use of the words "hate" and "hurt" to silence debate is contrary to the Western tradition of critical thinking. It is not hyperbolic to say that this is the pathway to censorship and the closing of the Western mind.

Richard Dawkins is one of the great thinkers of our time. It is curious to look back through history and to wonder which other intellectual and political giants of Western culture would receive the same treatment as Dawkins if they were to appear in the United States in 2018.

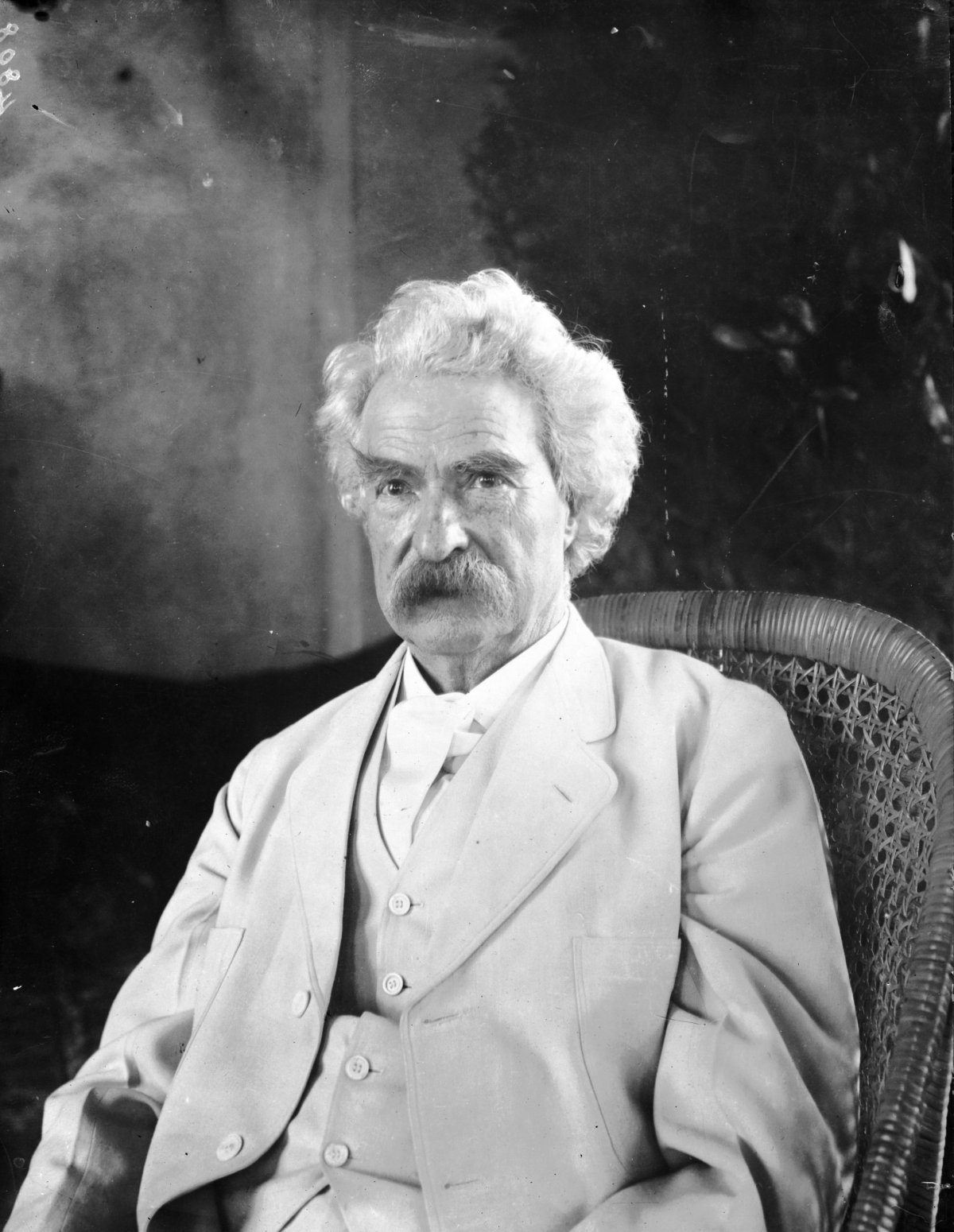

Considering their published views on Islam, we can assume that Thomas Jefferson, John Quincy Adams, and Mark Twain would all be de-platformed on American campuses today. So, too, would the great Enlightenment thinkers Montesquieu, Hume, and Voltaire.

And neither Winston Churchill nor George Bernard Shaw would be welcome at Berkeley. Although their views on Islam are not as easily digestible as a tweet and some of their language is archaic, they are not fundamentally different from Dawkins's.

"If Mahomet forbade free argument—Mohametanism prevented Reformation," wrote Thomas Jefferson in 1776, when reflecting on the dangers posed by Roman Catholicism (which, in his view, was also guilty of obscurantism). Islam, he argued, was just as guilty of "stifling free enquiry."

Even harsher was the language used by John Quincy Adams:

A wandering Arab of the lineage of Hagar [i.e., Muhammad] … spread desolation and delusion over an extensive portion of the earth. … He poisoned the sources of human felicity at the fountain, by degrading the condition of the female sex, and the allowance of polygamy; and he declared undistinguishing and exterminating war, as a part of his religion, against all the rest of mankind. THE ESSENCE OF HIS DOCTRINE WAS VIOLENCE AND LUST: TO EXALT THE BRUTAL OVER THE SPIRITUAL PART OF HUMAN NATURE [Adam's capitalization] …While the merciless and dissolute dogmas of the false prophet shall furnish motives to human action, there can never be peace upon earth, and good will towards men.

Admittedly, the original of this quotation does not bear Adams's signature, but Georgetown Professor Karine Walther, a reputable scholar, attributes it to him, as have other scholars.

Such ideas were commonplace at the time of the American Revolution, not least because they originated with the Enlightenment authors the Founding Fathers read.

"It is a misfortune to human nature," wrote Baron de Montesquieu, "when religion is given by a conqueror. The Mahometan religion, which speaks only by the sword, acts still upon men with that destructive spirit with which it was founded."

The great Scottish skeptic David Hume observed caustically that the Koran "bestows praise on such instances of treachery, inhumanity, cruelty, revenge, bigotry, as are utterly incompatible with civilized society."

His French counterpart Voltaire was in the same camp. "That a camel-merchant [Muhammad] … delivers his country to iron and flame; that he cuts the throats of fathers and kidnaps daughters; that he gives to the defeated the choice of his religion or death: this is assuredly nothing any man can excuse."

Perhaps the No Platform movement would argue that what happened in the 18th century should stay in the 18th century. But more modern authors have committed the same offense of "hate speech."

Take Mark Twain, who is well loved today for his anti-imperialism. "When I, a thoughtful and unblessed Presbyterian, examine the Koran," Twain wrote in his Christian Science , "I know that beyond any question every Mohammedan is insane; not in all things, but in religious matters."

Or how about George Bernard Shaw, in other respects a hero on the Left? "There was to be no nonsense about toleration" in Islam, wrote Shaw in a 1933 letter. "You accepted Allah or you had your throat cut by someone who did accept him, and who went to Paradise for having sent you to Hell." I doubt there would be an invitation, much less a disinvitation, for Shaw at Berkeley today.

A Conservative for most of his career, Winston Churchill remains the most famous British prime minister on both sides of the Atlantic. But he, too, would surely be de-platformed for writing this in his account of the British campaign in Sudan in the late 1890s:

The fact that in Mohammedan law every woman must belong to some man as his absolute property, either as a child, a wife, or a concubine, must delay the final extinction of slavery until the faith of Islam has ceased to be a great power among men. … The influence of the religion paralyses the social development of those who follow it. No stronger retrograde force exists in the world.

All of them are dead white males of Christian heritage, you may say. But would you also disinvite Kemal Ataturk, the founder of modern Turkey? "Islam," he once declared in an interview, "this theology of an immoral Arab—is a dead thing. Possibly it might have suited tribes in the desert. It is no good for modern, progressive state. God's revelation! There is no God!"

These quotations illustrate a simple point: societies since the Enlightenment have progressed because of their willingness to question sacred cows, to foster critical thinking and rational debate. Societies that blindly respect old hierarchies and established ways of thinking, that privilege traditional norms and cower from giving offense, have not produced the same intellectual dynamism as Western civilization.

Innovation and progress happened precisely in those places where perceived "offense" and "hurt feelings" were not regarded as sufficient to stifle critical thinking. De-platforming thinkers like Dawkins today is thus a betrayal of the values of the Enlightenment.

It's all the more sad that the censorship we are seeing on American campuses and in the public domain is self-imposed.

The latest in the growing body of literature on this subject is Douglas Murray's The Strange Death of Liberal Europe . Murray chronicles Europe's lack of civilizational self-confidence and inability to perpetuate its core values. Murray argues that European culture cannot survive its current bout of "civilizational tiredness" without suffering major and permanent damage to core European values.

Blinded by historical guilt and moral relativism, Europeans are increasingly willing to elevate other cultural values above their own, to the point of being unable to see why their own values are worth preserving.

Perhaps the most glaring illustration of Murray's point is the reluctance to subject the political and religious views of immigrants to the same scrutiny and critical debate applied to Western values. This is the very point Dawkins made in his response to the cancellation of his Californian event.

"Why," he asked, "is it fine to criticize Christianity but not Islam? … I am known as a frequent critic of Christianity and have never been de-platformed for that. Why do you give Islam a free pass?"

In a similar way, some progressives in the United States today refuse to acknowledge the difference between Islam as a spiritual belief system (relying on fasting, dietary restrictions, cleanliness, prayer), and the political and repressive system of Islamism that seeks to impose Sharia law on society.

Committed atheists and ex-Muslims like myself have no problem with the spiritual belief system that Muslims choose to follow. We do, however, oppose the blurring of religion and state that Islamism advocates. We oppose second-class citizenship for non-Muslims; the devaluing of a woman's testimony; the death penalty for those who leave Islam; and slavery.

We insist that sharia law in its current form is not compatible with liberal values. Prohibiting such arguments as "Islamophobia" is in fact contrary to the interests of Muslims themselves.

Speaking in a public setting about subjects such as the death penalty for apostasy in Islam is not uncivil; no harm is caused; no violence is done. When it comes to Islam, the No Platform brigade on our campuses is conflating ideas with individuals. You cannot cause physical or psychological harm to a set of ideas in the way you can to individuals.

It makes no sense to argue that submitting Islam to the same rational critique as any other set of ideas or religion is harmful. What is harmful is withdrawing the intellectual tools, such as critical thinking and exposure to rational debate, that many Muslims today crave.

It is crucial that all Americans understand the distinction between Islam and Islamism, so that we can have a meaningful debate about these issues. We cannot risk stumbling down the path that Europe has taken, as Murray warns, where almost no one will "dare write a novel, compose a piece of music or even draw an image that might risk Muslim anger."

We should remind ourselves why this debate is necessary. The major impetus has been violence committed by Islamists in the name of Islam. If there were no ISIS or Al Qaeda, we would be talking about Islam much less than we are today. If we wish to understand the behavior of those people invoking the Koran and Muhammad to justify terrible acts of violence, then Islam and Islamism cannot remain off limits as subjects for public discussion.

Should these questions be postponed until everyone feels emotionally comfortable talking about them? Or are there reasons to hold these challenging conversations now? I would argue that the increasing incidence of Islamist terrorist attacks in the last couple of years means we must debate these issues today.

Whether Islamist violence is perpetrated by new immigrants or established citizens, the isolation and ghettoization of Muslims (and especially Muslim women) in Europe and, increasingly, in the United States, creates an environment where Islamist advocacy is permissible and sometimes supported by communities.

And yet to point this out—to say that the rights of Muslim women are being curtailed—is denounced as "Islamophobia" by self-styled progressives.

Attempts to silence dissenting voices, particularly on college campuses, have recently gotten so out of hand that some state legislators are developing laws to enhance First Amendment rights at public universities. Such laws are already on the books in Colorado, Tennessee, Utah, and Virginia—and other states, including California, are considering them as well.

One of these laws passed last year in North Carolina prohibits college administrators from disinviting controversial speakers. It seems almost comical, and certainly tragic, that state governments feel the need to enshrine good manners in law.

Disinviting anyone to speak is of course bad manners, but in the Dawkins case and so many others, it also represents a clumsy attempt at censorship. The practice of de-platforming must end not just for the sake of politeness but for critical thinking. Free thought, free speech, and a free press were at the core of Western Civilization's success.

However uncomfortable free speech about Islam may be for some people, enforcing silence on the subject will do nothing to help those who are genuinely oppressed—above all the growing number of Muslim dissidents around the world whose courageous questioning of their own faith risks death at the hands of the very Islamists whose feelings progressives are so desperate not to hurt.

Ayaan Hirsi Ali is a research fellow at the Hoover Institution and the founder of the AHA Foundation.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.