The fact that a significant number of young Americans have refused to fall in line and respond with much enthusiasm during the final weeks of this presidential election has shocked and baffled the punditry. This indignation was already acute in September, when the trouble appeared to be a slim minority of white millennials driven by ideological discontent into the arms of third-party candidates.

Now we have discovered that a far greater number of young people across demographic lines are unmoved by the presidential candidates and consequently unwilling to affirm them, so they have dropped out of the process altogether. (Indeed, fully a quarter now glibly count a meteor strike among the more desirable outcomes of the election.) The commentary has become only more incredulous. The pundits wail: "Can't they see this is a crisis? This isn't a normal election. With so much on the line, what could they possibly be thinking?"

The theories proffered by the Serious and Sober analysts of American political life are astounding. One hardly needs to list them in particular, given how inadequate the whole mode of inquiry has proved. It relies, as it often does, on the assumption that the troubling behavior of large groups of people can be attributed to a failure of basic rationality: "They aren't realistic." "They lack information." "They don't have a sense of the stakes, aren't serious, haven't got perspective." Each of these explanations evinces, as always, the evident unfamiliarity of American pundits with the actual emotional experience of human life. "Why do so many people feel the economy is failing when projections for the gross domestic product are so positive?" Their world is explained in total by a dry assemblage of facts (worse: statistics), and if the behavior of people fails to correspond to the rational consequences of these facts, the trouble must be ignorance, willful or otherwise.

This is not to say that our emotional lives are disconnected from the conditions of the world. A more adequate theory of young minds during the final stretch of this election requires only the most cursory examination of the world they inhabit.

The country into which young voters have recently been born finds itself in a state of depravity. Forty-two million Americans, including 14 million children, do not have enough food. Despite gains made under the rapidly disintegrating Affordable Care Act, nearly 30 million Americans do not have health insurance. Neither of these facts results from lack of food or medicine, as 50 years spent pumping chickens and cows with our copious reserves of penicillin and tetracycline have brought about a glut of environmentally unsustainable farm animals and a world on the precipice of antibiotic-resistant infections.

Black Americans, 50 years after Jim Crow, remain precarious in their claim to citizenry, subject to daily harassment and theft routinely punctuated by outright murder at the hands of the state. Over 2 million Americans are in prison. Those fortunate enough to graduate college have a debt load virtually impossible to discharge by almost any legal avenue while prospects for employment remain scarce. Those fortunate enough to be employed have not seen their wages correspond to productivity in 40 years. The economy—insufficiently terrorized by the 2008 collapse, in part because the perpetrators of that collapse remain effectively in control of their own regulators—is haunted by the possibility of another shock. Who is doing well? Silicon Valley libertarians, promising to disrupt us back to 19th-century labor relations, cheered on by members of the notionally liberal party.

In September, atmospheric measurements confirmed that industrial output, driven in large part by the United States, has lurched the world past 400-parts-per-million atmospheric carbon dioxide. At least 2 degrees Celsius of global warming and its attendant catastrophes are nearly inevitable.

Remember too that even this tenuous arrangement of a nation is maintained only by a grinding, ambient violence, the occupation, torture and incineration of the citizens of no fewer than six sovereign nations at present, a world kept at bay by the 23,000 bombs dropped by the American military annually and a world that that, for all this effort, does not appear content to remain at bay much longer. We are closer than we have been in a generation to the real possibility of nuclear war.

(What can be said to all of this? That, generally speaking, global poverty is down? That medicine has advanced? That the slow inexorable grind of technology has made some great number of human lives superior to, say, those of a Frankish peasant? That, actually, the world is better than ever? It is strange that we take these signs to exonerate the present when they seem far more fitting as indictments of the past. The individual experience of human life has no regard for the abstraction of historical iniquity. What, after all, does incremental improvement mean in the face of global suicide? In the long term, permanent settlement for small encouragements resembles nothing so much as sinking deck chairs.)

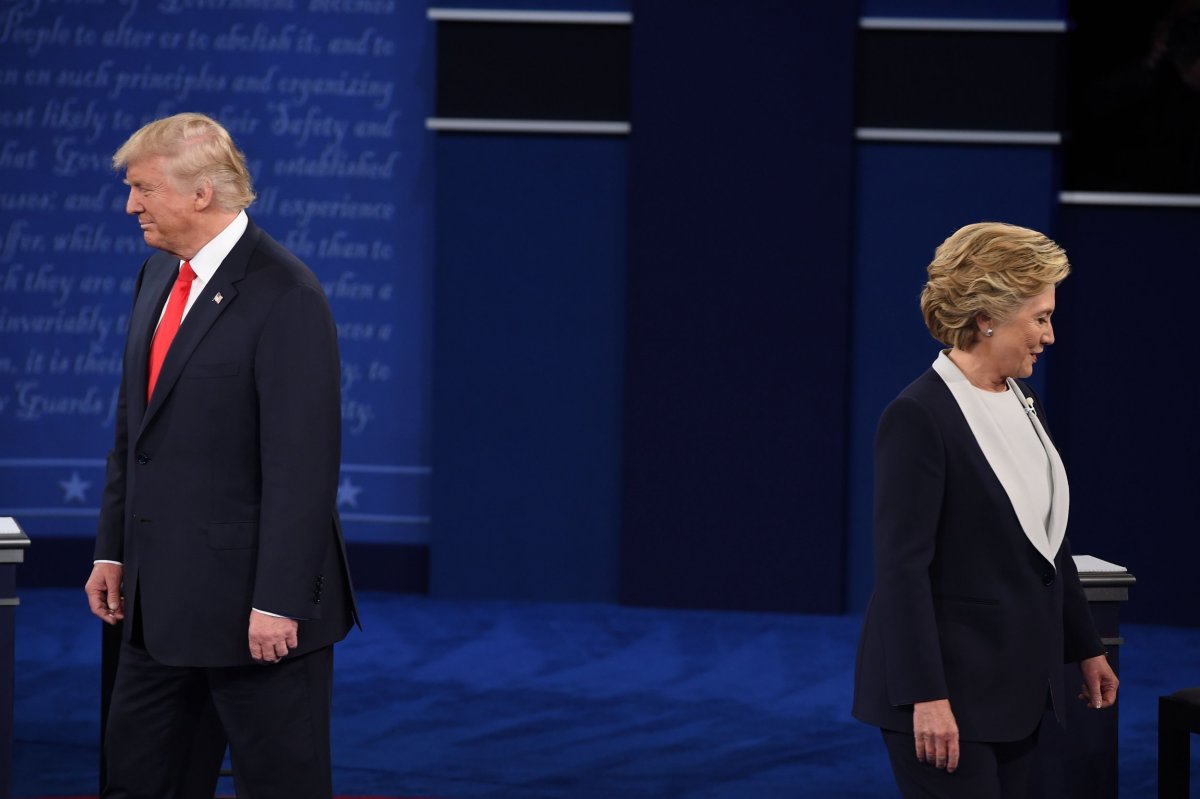

Now turn on any television set, read any newspaper, load up any political content outlet and note the utter inadequacy of the political solutions on offer. We are faced with a presidential election between a parody fascist and a breathing embodiment of liberalism's vaguely enlightened trepidations, the latter's marginal superiority achieved mainly by way of not being an incompetent or a rapist.

We have three debates to decide whether we prefer vulgar racism or barely bridled corporatism. Whether we ought to flatten the Middle East outright, or merely occupy it with "trainers" and special forces. One candidate says global warming is a Chinese hoax. The other, more grounded, is encouraged that we have achieved "energy independence" during the same week we learned that we cannot afford a single new oil well. (Don't worry. We're pursuing market-based solutions.) On one side, an isolationist trade war. On the other, the latest iteration of an internationalist trade regime dedicated the proposition that workers in the United States and in Asia ought to be more equal in their abject enthrallment to the aristocracies of both regions. Perhaps the poor can merely solve themselves by starving. Perhaps they can be helped by way of a welcome but narrow expansion of the welfare state, on the condition that they reproduce. The poverty those children inherit can be worked out later. The jackboot or the white shoe on your throat?

It is not that these choices merit equivalent concerns, nor even that they are looking upon this nightmare and explicitly refusing to address it. Rather, to watch the election unfold is to observe a contest that does not appear even dimly cognizant of the scale of our emergency. Either America is already great or, worst case, it is on the verge of becoming great again.

Back in the punditry, the pot calls out to the kettle: "What are young voters thinking? Can't they see this is a crisis?"

I do not want to suggest that the present sentiments of young voters amount to these articulated grievances. They are only the facts of the world as it is, and though disagreeable, the conditions of which we are all in some half-conscious way, unavoidably aware. One does not need to be terribly sophisticated, nor loyal to any particular ideology, in order to detect that something has gone wrong at the roots. What I am proposing is that young voters, and a great deal of older ones, have in their minds the ineradicable and subterranean suspicion that the whole world has lost the plot. What follows, what has followed, what we are seeing, are the early tremors of a consequent nervous breakdown.

It should not surprise us that young people are particularly susceptible to the anxiety produced by this state of affairs. The notion that adults may not ultimately have everything in hand is a common teenage conviction, but it is difficult, unless provoked by calamity, to really believe it.

What other conclusion can they reach? All around them are the klaxons of moral failure and catastrophe, yet should they turn to the journalists and analysts tasked with interpreting the world, young voters can find scarcely more evidence than they do amongst the candidates themselves that anyone has any sense of what is happening.

Instead, young people find a thousand digital and broadcast content mines engaged in endless bickering stupidity.

They find declarations that Liberalism is Working. That the real trouble is the menace of college kids who are too politically correct. They are told that the alumni of the Bush administration, just yesterday prime candidates for the Hague, must now be hugged in the name of civility. They are told through a fog of historical amnesia that Trump is an affront to our whole history, unprecedented in his proposed abuses of power, an inexplicable stain upon a nation that has actually imprisoned candidates for political dissent, blown up pharmaceutical plants, sold weapons to fund a Nicaraguan extremist organization and seen its presidents intern citizens, criminalize journalism, authorize torture, overthrow democratic governments and drop atomic bombs on cities filled with civilians. Richard Nixon tried to firebomb the Brookings Institute, burgle the Democratic National Committee and purge Jews from the executive branch. Barack Obama has deported more people than any other president in history. But Trump—we've never seen anything like this before.

They are told that all of this has something to do with the Russians.

Young people have watched the rise of racist nationalism amidst the ruins of neoliberalism. When they look for guidance, they find men whose résumés consist of "Ivy League" and "write a blog" being paid six-figure salaries to crack "economic anxiety" jokes and tell anyone proposing radical solutions to be more serious.

The most charitable interpretation is that these pundits too are afflicted by a sense of our catastrophe. Perhaps this is how they cope.

And indeed it is not as if we have all accommodated the bare facts of our reality in the same way. Even young people have varied wildly in their responses. Some take refuge in imitating the confidence of their elders, using social media as if they are sitting down their friends for an intervention: "No, really, just don't elect the madman, and everything will be fine." Like all such sermons, this is as much about shoring up the faith of the preacher as it is about his audience.

Others have rebelled, and they are the ones who captured the most notice. They have denounced the whole system, insisted they will support third parties, called the whole thing rotten and corrupt. They have been met with condescension, the baffling stupidity of well-intentioned commentators who assure them they understand and even agree with their goals, but that it would be unreasonable to do anything to bring them about. (Rather, they're told, they must bring about an entirely different outcome on the basis that it is preferable to Trump, with assurances that this will somehow result in their demands being taken seriously by an administration that no longer needs their votes.) This, at least, is familiar to minorities: They have long endured the same song and dance from liberals who assure them of their sympathies but disapprove of any "unruly" behavior intended to provoke reform.

This rebellion takes on different shapes, some less coherent than others. Few are able to explain, could possibly explain, how their behavior or their preferred candidates would address the world better—my God, Gary Johnson?—but this is beside the point. Revolt is a symptom of intolerable pressure. It does not require great foresight to constitute a rational reaction to the world.

Many, at least, have neither rebelled nor been brought into the faith of their elders. Many have simply stopped participating. They have retreated into the annihilating concerns of daily lives. Depression is not an uncommon response to the intolerable.

Still, the bulk persist, and so the question is not why the minds of the young voters are so troubled. That is clear enough. The question is how so many of them have nonetheless managed to keep their fingers crossed, to play their part, to at least go through the motions that the world demands of them when the bulk of the evidence contradicts the sense that doing so is any use. The minds of young people were shaped by the promise of a hopeful future. Instead, they are poised to inherit a nation dizzy from its own contradictions, the best ticket on offer a mere aversion of immediate demise. What does it mean, given this, that even a small defection is so intolerable to the punditry?

All of this has happened before. It has happened more or less in every generation. A mounting dread at the inadequacy of human effort in the face of scarcely comprehensible suffering is, in many ways, the great cliché of political maturation—the young people rebel, until they don't and turn around to suppress the rebellion of their children. Power bends to accommodate the more odious of injustices and leaves the larger parts untouched. Even the present set of indictments against the American state have, with a few exceptions, long lurched into the realm of platitudes.

Incarceration, right-wing nationalism, the inadequacy of liberalism, endless global wars—we've been hearing it for decades. We've survived so far. The best strategy power has to best its critics is to let accusations, arguments and demands for justice beat like unnoticed waves against the rocks of bureaucracy. If finally forced, the powerful can just reply: "Yeah. It's wet outside. What else is new?" Thus critique becomes a cliché.

What, anyway, could be done? The whole structure of American politics, the economy that ushered us to the brink of catastrophe is jerry-rigged to reproduce itself every election and financial quarter. "All this water is a problem," the powerful might admit. "What would you like to do? Drain the ocean?"

I am and have long been a socialist, but I am not ignorant of the fact that this avenue is not poised to seize national power, nor terribly likely to be so poised in time.

What is perfectly clear, at bottom, is that there is no presently feasible course of action commensurable to the afflictions of the world. Yes, the majority of voters and the great majority of young voters will do their duty. Clinton will be elected president of the United States. Though this will avert the immediate threat of national suicide, it will do nothing to quiet the suspicion that we are all of us now merely jogging toward destruction. This is what maddens. If the past eight years are any guide, the feeling will only intensify.

We have stopped the bleeding, but we are still sick. The tourniquet will not comfort the jailed or the incinerated. The reassurances of self-appointed experts will not feed the starving. The planet that has seen every generation play out this desperate psychodrama will not wait any longer, and this, at last, is the really dangerous thing. We have endured for a while, but how much longer? When the water rises and the crops fail—then what? The madness grows, and the inchoate righteous terror of our polity, once again rebelling against the inadequacy of whatever limp response we sign a nonbinding intention toward, will find themselves once again and for perhaps the final time dismissed by the bland coos of the Serious and Sober. "Be realistic," they'll blog. "This is how the world works."

But we know that. We know, we know.

Can't you see that's the problem?

Emmett Rensin is a writer based in Iowa City, Iowa. His previous work has appeared in Vox, The New Republic, The Atlantic and The Los Angeles Review of Books (where he is a contributing editor). Follow him on Twitter at @EmmettRensin.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.