Zaha Hadid, who died Thursday at the age of 65, was without question one of the foremost architects in the world. Winner of the 2004 Pritzker Architecture Prize, she became the profession's most prominent female practitioner. She was also one of modern architecture's few stars from the Arab world. "The moment my woman-ness is accepted, the Arab-ness seems to become a problem," Hadid told The Guardian in 2012.

Hadid's obituaries will rightly focus on the audacious geometry of her most famous buildings, including the London Aquatics Centre, China's Guangzhou Opera House and the Riverside Museum in Glasgow, Scotland. These are buildings as works of art, buildings to weather both time's passage and changing tastes. Any one of them would have made the career of a lesser architect. Hadid had done plenty and, surely, had plenty more to do.

But evaluations of Hadid's career will also have to grapple with something less seemly: her occasional denial that there were any ethical implications to her projects. In 2012, she completed the Heydar Aliyev Center in Baku, Azerbaijan. Aliyev had been Azerbaijan's dictator; the country is currently ruled by another dictator: his son. The "modernization" of Baku, including the building of the Aliyev Center, was reportedly marred by forced evictions and the use of forced labor. If this troubled Hadid, she never showed it.

Others questioned her (aborted) work in Muammar el-Qaddafi's Libya; she worked in China and Russia too. Many other architects have designed buildings in countries with troubling human rights records, but, somehow, there was a sense that Hadid was more willing to make compromises than most. Did she engender ill will in some small part because she was an outspoken brown woman in a field dominated by white men? I don't doubt it. Whatever the case, she continued to face criticism.

"The locality Hadid prefers is the backyards of dictators and tyrants," a critic for conservative British weekly The Spectator wrote in 2012. "Her latest buildings always win approval from supine architecture and design media, so work very well as salvation-via-design for repressive regimes."

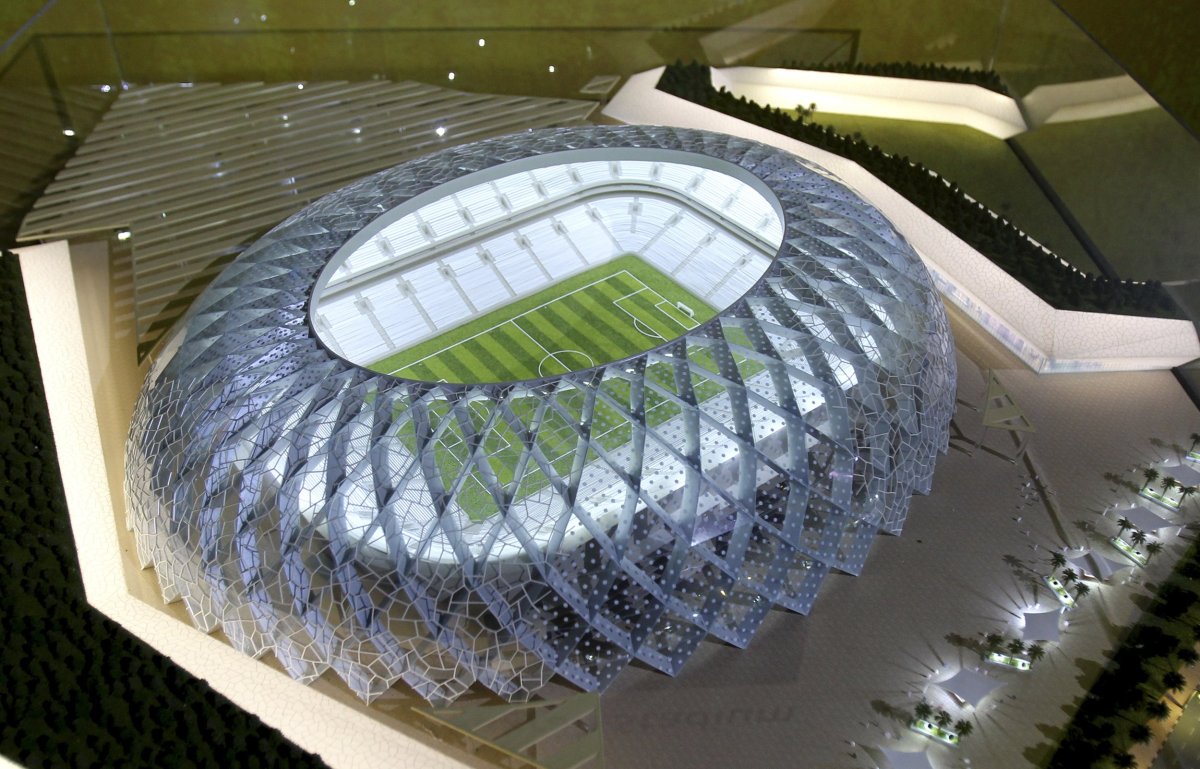

Her most fraught project was the Al Wakrah Stadium in Qatar, for the 2022 World Cup. As it became increasingly clear that the Qatari government was treating construction workers like slaves, Hadid railed against those who brought the accusations to her. Confronted with the fact that nearly 1,000 workers had died in other projects related to World Cup construction, Hadid said, "I have nothing to do with the workers. I think that's an issue the government—if there's a problem—should pick up. Hopefully, these things will be resolved."

Hadid may have been factually correct, but the mere affiliation with Qatar seemed to confirm long-standing suspicions. She continued to defend Al Wakrah, sometimes perhaps to the detriment of her own reputation. The most notable such instance came in 2014, when Martin Filler wrote mistakenly in The New York Review of Books that the worker deaths were at Al Wakrah. This was untrue, but instead of merely asking for a correction, Hadid sued for defamation of character, eventually winning damages (which she donated to a charity) and an apology.

Some thought Hadid came out the loser in her fight with Filler. Before settlement of the case, architecture critic Paul Goldberger wrote in Vanity Fair that Hadid bore an ethical responsibility to the migrant laborers in Qatar, regardless of whether they were working on her project or not. "Yes, she risks losing a job if an angry government fires her for being outspoken, but it is hard not to believe that she would gain four more jobs from people admiring her for taking a brave stand. No one forces an architect to accept a job that carries with it a serious ethical compromise," Goldberger said.

A day before Hadid died, Amnesty International released a report on the appalling conditions surrounding the construction of Khalifa International Stadium in Qatar. Again, not a Hadid project. But again, you do wonder.

Artists often work in the service of dictators and despots: sometimes unwillingly, sometimes not. Gertrude Stein was a little too friendly with the Vichy government of Nazi-occupied France. There were questions in 2012 about whether Mo Yan, the Chinese writer—whom Salman Rushdie labeled a "patsy" of the Communist Party—deserved the Nobel Prize. Plenty of other artists, whether in Stalinist Russia or the Jim Crow South, had the chance to say something but didn't. Maybe that allowed them to work in peace, but maybe it also marred the work they left behind.

Hadid's complex legacy reminds us that genius does not operate in a dustless ether of abstractions. It matters where the buildings are built, as well as who builds them.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.