In February, scientists announced that there is an eighth continent submerged beneath the ocean, and its name is Zealandia. In a paper published by the Geological Society of America, the team of scientists called the area "Earth's hidden continent" and suggested that identifying it as such will help us better represent our planet and improve our understanding of its history and the processes that drive it.

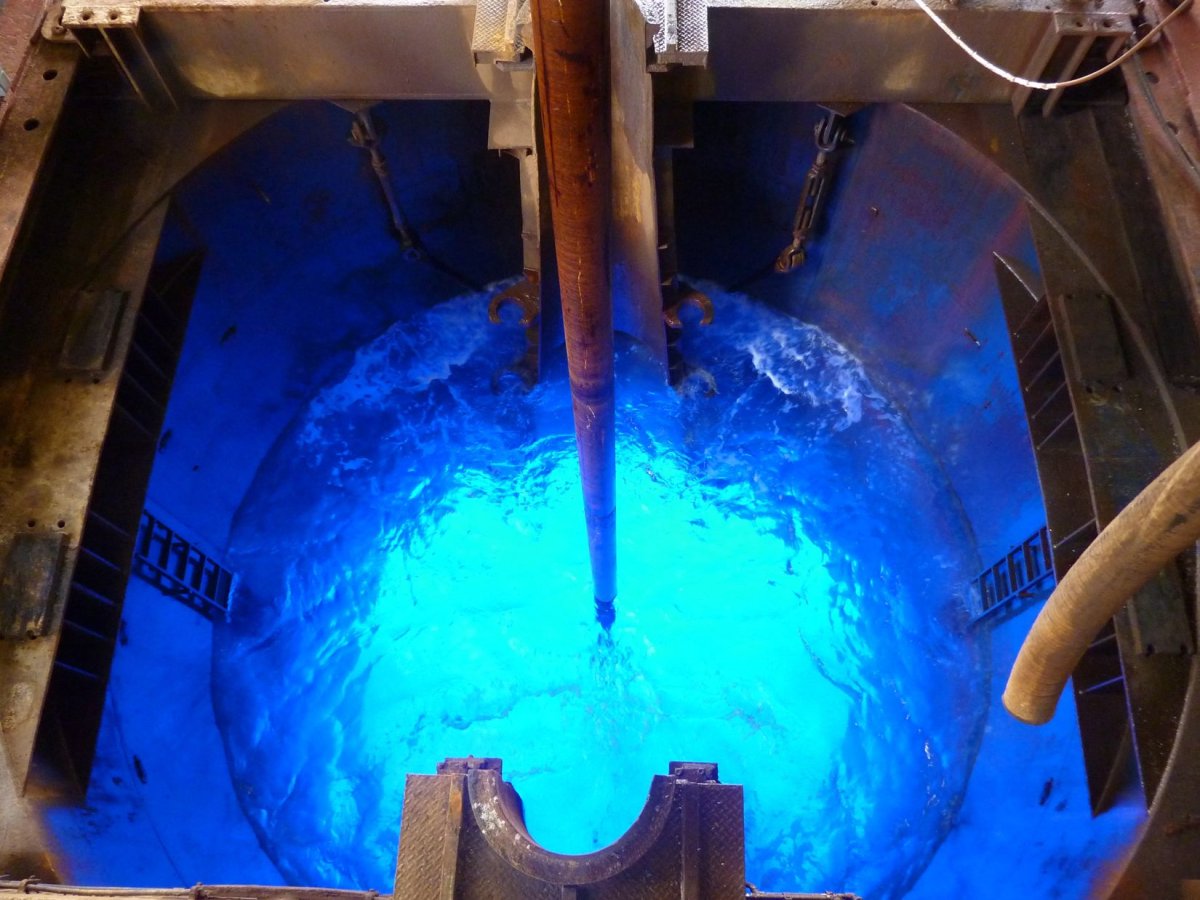

Now, a team of scientists with the International Ocean Discovery Program will study Zealandia by drilling into part of the 2-million-square-mile mass of continental crust. It broke away from Australia about 80 million years ago and sank; now, about 95 percent of it is submerged beneath the Pacific Ocean. The two-month expedition, conducted by 30 scientists from a dozen countries, will set sail on July 27. The researchers plan to drill at six different sites, collecting samples of sediments more than 1,000 feet into the seafloor. That will allow scientists to analyze the fossil evidence in order to build a record of how Zealandia changed over time.

A lost landmass that's sunk into the sea: sounds like Atlantis, and scientists agree. "It's an Atlantis, but for dinosaurs," says Stephen Pekar, a professor of earth and environmental science at Queens College, City University of New York, who will be aboard the drilling ship JOIDES Resolution for the duration of the mission. Pekar explains that Zealandia sunk in the time of the dinosaurs, "but then for some reason it started rising about 50 million years ago. And then it started sinking yet again."

The idea of Zealandia was first put forward more than 20 years ago. For decades, scientists have made cases for Zealandia to be recognized as a continent. The GSA paper clearly defined it as such, showing how it reached the criteria to be classified as a continent. New Zealand and its surrounding islands are made of mountains of a lost landmass, rising above the sea.

"If you go way back, about 100 million years ago, Antarctica, Australia and Zealandia were all one continent," Gerald Dickens, co-chief scientist of the IODP expedition, said in a statement. "Around 85 million years ago, Zealandia split off on its own, and for a time, the seafloor between it and Australia was spreading on either side of an ocean ridge that separated the two."

Jamie Allan, a program director with the National Science Foundation, which is helping to fund the project, said: "Some 50 million years ago, a massive shift in plate movement happened in the Pacific Ocean. It resulted in the diving of the Pacific Plate under New Zealand, the uplift of New Zealand above the waterline and the development of a new arc of volcanoes. This expedition will look at the timing and causes of these changes as well as related changes in ocean circulation patterns, and ultimately Earth's climate."

Pekar explains that the scientists' analysis of these ancient sediments will allow them to reconstruct the climate at that time in history. That's important, since around the time Zealandia started sinking for a second time, the atmosphere had a similar level of carbon dioxide but the Earth was much, much warmer. A better understanding of the relationship between carbon dioxide concentrations and world temperatures can help fine-tune our models goinfg forward. "I like to think of it as looking back to the future," Pekar says.

Understanding how that area changed over millions of years will help answer fundamental questions about our planet, including how the climate evolved over the last 60 million years. Because the continent is left out of most climate models, including it could help address some of the discrepancies in Earth's climatic history. "It's a missing piece of the puzzle," says Pekar.

"When the community does climate modeling for the Eocene Epoch [56 to 33.9 million years ago], this is the area that causes consternation, and we're not sure why," Dickens said. "It may be because we had continents that were much shallower than we thought. Or we could have the continents right, but at the wrong latitude. The cores will help us figure that out."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Hannah Osborne is Nesweek's Science Editor, based in London, UK. Hannah joined Newsweek in 2017 from IBTimes UK. She is ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.