It was just another colorless trade show, one of thousands held each year in hotels across the United States. But it was there, at an Embassy Suites in Franklin, Tennessee, that the simple handoff of a business card proved to be the first link in a two-year chain of events that led to the horrific, tortuous deaths of the first victims in a mass killing that trailed from New England to Tennessee, from Michigan to North Carolina.

Health workers packed the hotel for the annual meeting of the Freestanding Ambulatory Surgery Center Association, hoping to network, listen to medical presentations and meet industry salespeople plying their wares. Among the hundreds wandering about on the second day of the conference—September 24, 2010—was John Notarianni, regional sales manager for the New England Compounding Center (NECC), a Massachusetts pharmacy. Like any good salesman, Notarianni was glad-handing prospects while passing out business cards and advertising material. At some point, he crossed paths with Debra Schamberg, a nurse and facility director with the St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center in nearby Nashville.

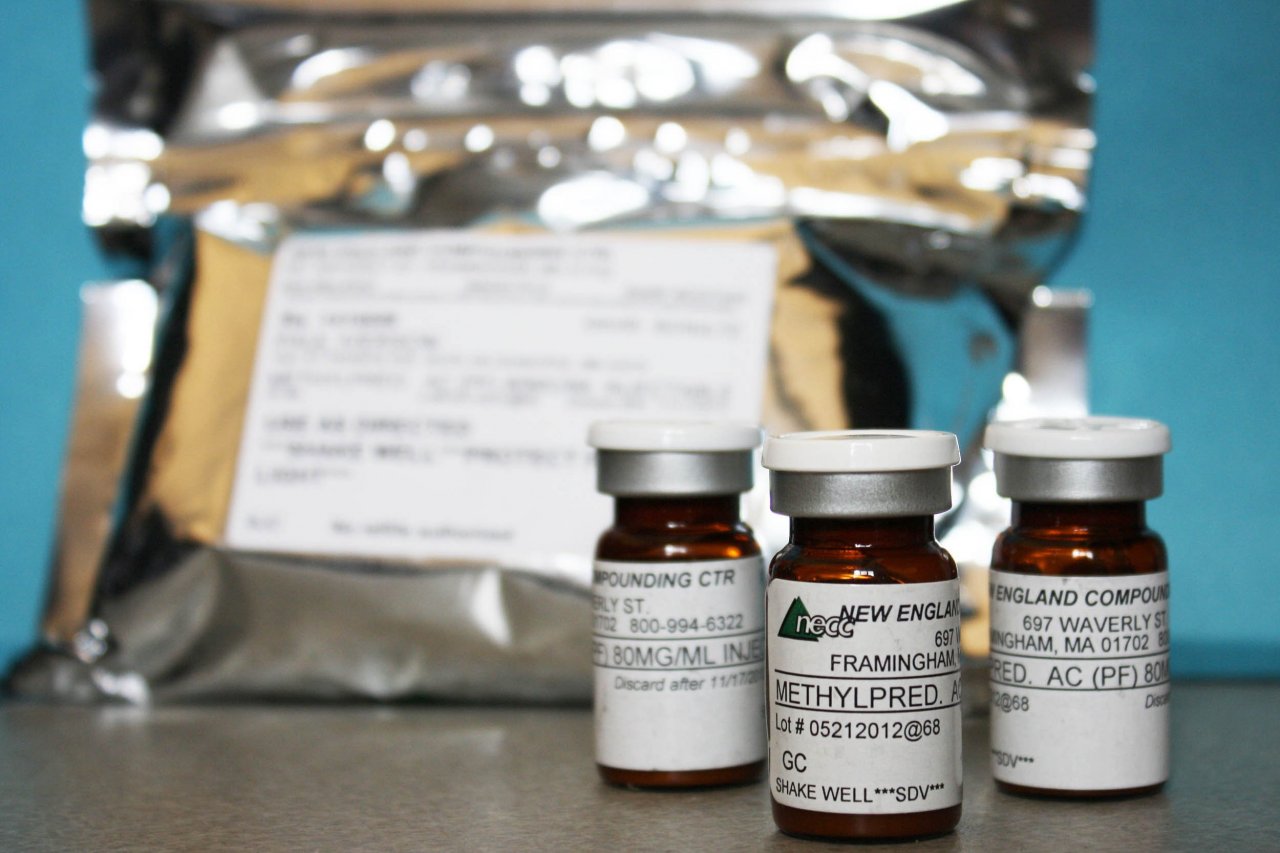

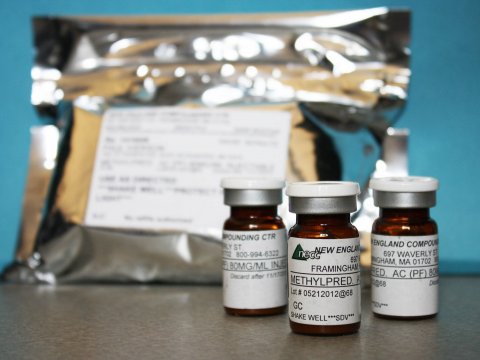

For a few minutes, Notarianni pitched his company, telling Schamberg about the pharmaceuticals NECC had available, including injectable methylprednisolone acetate, a steroid commonly used for pain management. Since her outpatient center spent much of the workday injecting steroids into hips, joints and backs, Schamberg was intrigued. She took Notarianni's business card and pamphlets and then went on her way, thinking she may have found a great alternative to the usual pharmacies the outpatient center used.

But NECC wasn't a promising drug supplier—it was a lethal, venomous scourge. This seemingly innocuous pharmacy in a Framingham strip mall was making millions of dollars by cutting corners, fabricating records and ignoring laws designed to keep contaminated drugs off the market. NECC perpetrated what may be one of the most murderous corporate crimes in U.S. history by pumping out deadly medicines that infected more than 800 people with fungal meningitis in 2012, 64 of whom died.

The outbreak traced to this one pharmacy set off investigations by federal and state health officials, the Justice Department and Congress. Three months ago, a federal grand jury indicted 14 people who worked for or were connected to NECC on 131 charges, which included assorted counts of murder, racketeering, fraud, conspiracy and other alleged crimes.

Despite the scale of the killings and the scope of the investigations, the inside story of the events that led to the lethal outbreak and its discovery is being told for the first time here. Newsweek's examination of the NECC deaths was pieced together from emails, order forms, investigators' notes, drug company and court records, and sworn statements of participants, as well as interviews with people connected to the case.

No More Mickey Mouse!

The murderous tale begins with that innocuous meeting between Notarianni and Schamberg, neither of whom was ever charged with wrongdoing and may well have been no more than unsuspecting pawns in a cruel and deadly multimillion-dollar scam.

Like any good salesman, Notarianni called Schamberg every few months after their encounter at the trade show, urging her to purchase the steroids and other drugs sold by his company. "I went back to my manager, and he said he really would like to offer you better to earn your business,'' Notarianni wrote in an email on May 17, 2011. "What price would we need to give you to gain your business on the [injectable steroids]?"

Notarianni's timing could scarcely have been better. Within a few weeks, Clint Pharmaceuticals, the outpatient center's usual supplier of injectable steroids, boosted its price by $2.46 per 1-milliliter vial of the drug, to $8.95; the cost of sterile manufacturing was climbing and supply was shrinking. Schamberg pushed Clint for a better deal, but no go. So she typed an email to Notarianni on June 11, 2011: "If pricing is still $6.50 [per vial], I am willing to do business with you."

Over the next few months, officials with St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center sent orders to NECC. Mario G. Giamei Jr., Notarianni's successor as regional sales manager, took over the account, court records show. Things between NECC and the outpatient center continued to go well until around early 2012, when Giamei, who has not been charged with wrongdoing, dropped by the clinic and told Schamberg a problem had emerged—NECC needed a lot of patient names, and fast.

Unlike a drug manufacturer or wholesaler, NECC was a compounding pharmacy, licensed only to sell medications to fill individual prescriptions. In other words, it wasn't allowed to market drugs in batches to clinics and doctors—even though that was exactly what it was doing. NECC was conducting business like a manufacturer while being regulated as a pharmacy.

NECC began selling large shipments of drugs without prescriptions as early as 2009. That year, some health care providers who wanted the convenience of having their prescription drugs in stock—which helped them speed up how quickly they could see patients—had complained about NECC's prescription requirements. On September 15, 2010, Barry Cadden, the president and head pharmacist at NECC, sent an email to Robert Ronzio, the national sales manager, regarding a prospective client that was balking at the idea of assembling and providing all the prescription paperwork. Perhaps, Cadden said, NECC didn't need the prescriptions but instead could just attach names to the orders at some point—even after the medications were injected. That way, if regulators checked, they would see every dosage linked to a patient.

"We must connect the patients to the dosage forms at some point in the process to prove that we are not a [manufacturer]," Cadden wrote. "They can follow up each month with a roster of actual patients and we can back-fill."

There were two problems with that plan. First, it was illegal. Second, obtaining patient names from clinics and other medical providers after drugs had been injected was time-consuming. By the following year, some customers were just submitting the names of people on their staff, which Cadden thought was dangerous. "There are better ways to do this,'' he wrote in a May 2, 2011, email. "Same names all the time makes no sense."

NECC's various schemes to get around the prescription requirement ran from the clever to the absurd. Some customers were exempted from sending names, while others provided names that were ridiculous. Big Baby Jesus was listed as having received an injection at a facility in San Marcos, Texas; so were Donald Trump, Calvin Klein, Jimmy Carter and Hugh Jass. A facility in Lincoln, Nebraska, placed orders for Silver Surfer, Hindsight Man, Octavius and Burt Reynolds. And orders came in from Elkhart, Indiana, for Filet O'Fish, Squeaky Wheel, Dingo Boney and Coco Puff.

That kind of silliness stirred up outrage back in Massachusetts. On March 20, 2012, Alla Stepanets, an NECC pharmacist, sent an email to a sales representative complaining about a customer saying that "[the] facility uses bogus patient names that are just ridiculous!" The sales representative replied that "[t]hese are RIDICULOUS." But no matter—Stepanets told the sales representative the order was sent anyway.

By early 2012, St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center had been an NECC customer for more than six months but had not yet been told of the need to provide patient names. It was then, according to court documents, that Giamei, the recently appointed regional sales manager, told Schamberg, the clinic's facility director, that the pharmacy needed to start receiving names with the outpatient center's drug orders.

That was impossible, she replied. There was no way to predict at the time of the order which patients would be receiving the drugs. That wouldn't be a problem, Giamei replied—NECC just needed a list of patient names. Schamberg consulted with the medical director, Dr. John Culclasure, and then a receptionist suggested printing out daily patient schedules and submitting those with each NECC order. That idea was put into practice right away, but still, just like at other clinics, employees at St. Thomas couldn't help but have a little fun—one of the patient names they submitted to NECC was Mickey Mouse, although no one at St. Thomas has been charged with wrongdoing.

The use of the cartoon character's name set off more anger at NECC. On May 21, 2012, Cadden, NECC's president, sent a steaming email to Sharon Carter, the director of operations. Carter added to the email, then printed it out and posted it in the office. "A facility can't continuously provide the same roster of names.....unless they are truly treating the exact same patients over and over again!'' the email said, with all the ellipses. "All names must resemble 'real' names............no obviously false names! (Mickey Mouse.)"

The Filthy Clean Room

That same day, as NECC executives were fuming about obviously fake names, a horror was unfolding just yards away from them in another part of the company's Framingham offices, one that ultimately would lead to the painful death of scores of patients.

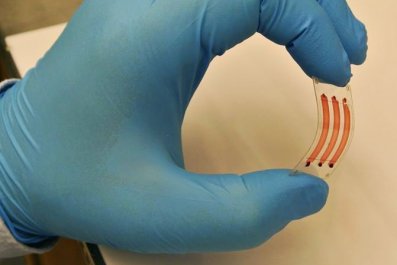

Even as Cadden was typing his angry email, Glenn A. Chin, a supervisory pharmacist at NECC, stepped over a dirty mat into an area known as the Clean Room. According to government charges, Chin prepared a 12.5-liter stock of the injectable steroid methylprednisolone acetate, which was labeled with the lot number 05212012@68. Proper sterilization procedures required exposing the drugs to high-pressure saturated steam at 121 degrees in an autoclave for at least 20 minutes.

Chin used the autoclave for only 15 minutes and four seconds, almost five minutes short of the minimum time required—a shortfall that, if extended over an eight-hour day, would allow for at least two extra batches of drugs to be produced. And this was not a one-time error; charges filed by the government suggest that shortchanging the autoclave process was standard operating procedure at NECC.

There were plenty of reasons to fear that steaming the compounds for too little time was dangerous. Surface and air sampling for each of the prior 20 weeks had detected contamination in the air and on the surfaces of NECC's Clean Room—and even on the hands of Chin and other staffers. But NECC regularly and blatantly ignored the laws on decontamination, according to the government charges. Chin allegedly instructed subordinates to prioritize faster production over sterilization and ordered them to falsify documents to suggest they had cleaned areas when they had not.

There were other hazards in that Clean Room: a leaky boiler stood in a pool of stagnant water; powder hoods, which are designed to suck microscopic particles out of the room, were covered with dirt and fuzz; and the air intake came from vents that were about 30 yards from a dust-spewing recycling plant.

Still, these sloppy procedures alone did not put the public at risk. Under the law, once the manufacturing of a drug batch was completed, NECC was required to conduct a series of comprehensive tests to make sure the medication was sterile. For compounding pharmacies that follow the rules—making small quantities of drugs to fill individual prescriptions—the tests were hardly burdensome. But by illegally acting as a manufacturer and creating mass batches of drugs—while telling regulators it was mixing one order at a time—NECC had decided to simply ignore the safety check procedures. After all, how could a company comply with rules designed for testing five or six vials of drugs when it was illegally manufacturing thousands for sale all over the country?

And so Lot 05212012@68 was scarcely tested. Its safety was supposed to be verified by a process involving what is called a biological indicator; that rule was ignored. Also, although the entire batch was required by law to be tested for sterility by an independent laboratory, Chin sent only 10 milliliters of drugs in two vials for analysis. On June 5, after the lab found that the first vial tested was sterile, officials at NECC declared the entire lot ready for shipment. In other words, the batch was deemed safe for injection into humans based on the testing of just 0.0004 percent of the total. This would be the equivalent of a grocery store deciding that all of its fruit is fresh after taking a bite of a single apple—except that customers can spot spoiled fruit on their own…and a rotten apple won't kill you.

On June 8, NECC started filling orders for injectable steroids from Lot 05212012@68. Over the next seven weeks, 6,500 vials of injectable steroids were shipped to customers around the country. St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center's order of 500 vials was filled on June 27, 2012. Unknown to anyone, many of those tiny bottles carried a deadly fungus.

Thirty-three days later, on July 30, Thomas Rybinski, a 56-year-old autoworker from Smyrna, Tennessee, walked into Nashville's St. Thomas Hospital, a building of concrete and tinted glass that resembles a monstrous, ill-formed wedding cake. He took the elevator to the ninth floor and entered the office of St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center. He had come for a steroid injection for chronic back pain caused by a degenerative disk disease.

In the exam room, a doctor screwed a needle onto a syringe, inserted it into a 1-milliliter vial of liquid steroid and pulled back the plunger to fill the syringe. Then he carefully slid the needle into Rybinski's back, near his spine. As the doctor slowly pushed down on the plunger, he was unknowingly injecting a microscopic fungus that had been floating unseen inside that contaminated vial.

Knowing He Would Soon Die

Dr. April Pettit was perplexed. The 34-year-old internist at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville had been reviewing the medical records of Rybinski, and nothing made sense. In late August, Rybinski had come to the hospital complaining of nausea and fatigue. After running blood tests, a spinal tap and a CAT scan, the medical team diagnosed him with a community-acquired meningitis. He was loaded up with antibiotics and sent home.

A week later, Rybinski's family brought him back to Vanderbilt. His speech was incomprehensible. He was agitated and suffering headaches. Another spinal tap was followed by intravenous antibiotics, and again Rybinski seemed on the mend. But on his sixth day at the hospital, he showed signs of seizures, and the right side of his face drooped.

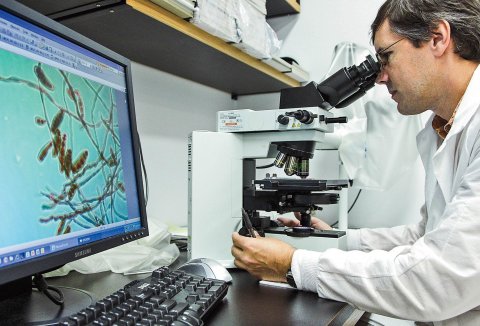

Pettit then had a thought—a long shot. Bacteria were the most frequent cause of meningitis, but could the problem here be a far rarer scenario of fungal meningitis? Pettit told the lab to reexamine Rybinski's spinal fluid, this time checking for fungus. The results came back positive for Aspergillus fumigatus, a fungus that looks like a monstrous dandelion and is usually found in decaying organic matter, like a compost heap. Yet somehow it was growing inside a Tennessee autoworker, and slowly killing him.

Pettit and other doctors went to Rybinski's family, quizzing them about anything unusual he might have done in the weeks before symptoms started appearing. Someone mentioned the steroid injection at St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center for his chronic back pain.

As the doctors worked on piecing the puzzle together, the fungus from NECC was tearing Rybinski apart. Brain tissue died as vessels that bathed the areas in blood became blocked or leaked. On his 11th day in the hospital, Rybinski abruptly became unresponsive and started shaking his head rhythmically. He was placed on a ventilator, but his brain started to swell. Doctors cut a hole in his skull and set up a catheter to drain excess liquid. He showed signs of an aneurysm and continued to have seizures.

At that same time, in another part of the hospital, 78-year-old Eddie Lovelace was barely clinging to life. He had suffered what seemed to be a mild stroke but had been expected to recover; then his health started to deteriorate. His family gathered by his hospital bed, knowing he would soon die but not knowing why. His 98-year-old mother telephoned him to say her goodbyes, telling her son that he was her "dear, sweet boy."

On September 17, 2012—less than a month after his last steroid injection at St. Thomas Outpatient Neurosurgery Center—Eddie Lovelace died. Unknown to his doctors, he had been killed by fungal meningitis. He was the first victim of NECC's heinous crimes, a link that wouldn't be discovered for weeks.

The next day, unaware that a patient at Vanderbilt had just died from the same infection she had discovered in Rybinski, Pettit was still scrambling to deal with his rapidly deteriorating condition. She emailed the Tennessee Department of Health on September 18 with a copy of the lab results showing the fungal infection. State officials immediately asked for more information. Then they called St. Thomas Hospital—where the Outpatient Neurosurgery Center is based—and discovered doctors there were treating two other patients suffering from meningitis. Both patients had also received steroid injections.

As health officials in Tennessee scrambled, Giamei, the NECC regional sales manager, dropped by the St. Thomas outpatient center on September 24. According to court records, Schamberg, the facility director, and Culclasure, the medical director, spoke to him about the meningitis outbreak. "This could not possibly be coming from us," Giamei stated confidently, adding that NECC complied with all sterility procedures and had a state-of-the-art facility. Perhaps they should come for a visit to Framingham, he suggested, just to see the quality of the company.

By the next day, September 25, state officials working alongside the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) had identified eight patients with meningitis, all of whom had received steroid shots at the outpatient center. Health officials called NECC to inform it of the investigation and to identify the lot numbers of the steroids linked to the deaths, but NECC executives said there had been no other complaints about these drugs. Within 24 hours, state health agents in Massachusetts raided NECC. They were horrified by what they saw. While a few employees were desperately scrubbing the Clean Rooms with bleach, the filthiness of the place could not be covered up. Every lot of NECC steroids suspected of being contaminated was recalled that day.

But it was too late. The next morning, September 27, officials at the CDC received the worst news possible—the outbreak was not limited to Tennessee. State health officials in North Carolina called to report that a patient at High Point Regional Hospital was suffering from meningitis with the same symptoms as the Tennessee patients. The patient, Elwina Shaw, had received a steroid injection a few weeks before at the High Point Surgery Center, a NECC customer.

The day after health officials reported her condition, Shaw suffered a stroke. And less than a day later, Thomas Rybinski, the autoworker whose case first alerted health authorities to the emerging crisis, died at Vanderbilt Hospital.

Dressed and Ready to Go to Jail

The NECC meningitis outbreak sickened and killed patients in 20 states. The worst hit was Michigan, with 264 cases and 19 deaths. Tennessee had the next worst toll, with 153 cases that left 16 people dead. Hundreds of lawsuits were filed—against NECC, its executives, their related companies, the outpatient centers and the hospitals. NECC filed for bankruptcy in December 2012, and the court issued two rulings enjoining the executives and owners from moving their money. Almost immediately after the first order was handed down, Carla Conigliaro, the majority shareholder of NECC, and her husband, Douglas Conigliaro, transferred $33.3 million to banks in a series of 18 transactions in violation of the court's instructions, according to the government indictment.

By the fall of 2014, NECC's once-respected executives and pharmacists knew they faced criminal prosecution for a wide range of serious offenses. On September 4, Glenn Chin, the supervising pharmacist, was arrested at Boston's Logan Airport as he prepared to board a flight with his family for Hong Kong. Then, on December 17, federal agents launched a series of pre-dawn raids, arresting 14 NECC executives, owners and staffers. Cadden, the company's president, was dressed and waiting when law enforcement officials reached his door; he was expecting them and had climbed out of bed at 4 a.m. so he would be ready to go when they knocked on his door.

In U.S. District Court in Boston, all 14 defendants pleaded not guilty to a wide assortment of crimes, including racketeering, fraud, conspiracy, violating federal drug laws and financial crimes. Only Cadden and Chin have been charged with murder. They face a maximum sentence of life in prison if convicted on all counts.