On the morning of September 6, 1960, Cassius Clay was having breakfast with a few buddies inside the Olympic Village in Rome. The night before, Clay, 18, had defeated 25-year-old Ziggy Pietrzykowski of Poland in the light-heavyweight boxing gold medal match, igniting the flame of his magnificent pugilistic career. As Clay sat in the dining hall with a few members of the U.S. contingent, heavyweight world champion Floyd Patterson entered the room.

"Watch this," Clay told his friends, and then, as recounted in Rome 1960 by David Maraniss, he grabbed a knife and fork and leaped on the table. "I'm having you next!" the brash teenager bellowed at the heavyweight champ as everyone, including Patterson, burst into laughter. "I'm having you for dinner!"

Muhammad Ali, born Cassius Clay, died in Phoenix on Friday, June 3, at age 74 of respiratory illness and complications related to Parkinson's disease. Some kings wear crowns. The Greatest simply wore a heavyweight championship belt.

Few athletes have been as dominant in their chosen sport: Ali was a three-time heavyweight champ whose career spanned three decades. He had a 55-2 record before losing three of his final four bouts, ill-advised fights he accepted long after he should have made his egress from the ring. Of those first two blemishes on his career record, though, losses to Joe Frazier and Ken Norton, Ali would find redemption by later beating each of those men—twice. (He beat Patterson too, five years after he stood atop that table.)

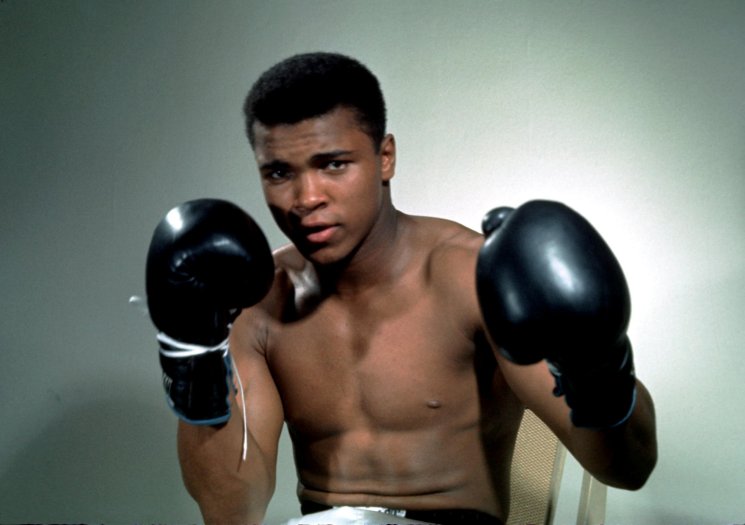

Boxing was his occupation, but Ali was a colossus of culture. He was by far the most charismatic athlete of the 20th century: passionate and ebullient, articulate and garrulous, self-absorbed but self-aware. He was undaunted by the stature of his opponents or by the divisive racial years during which he entered his prime. At a time when leaders of the civil rights movement were marching peacefully, locking arms and singing "We Shall Overcome," Ali was standing defiantly over the prone figures of boxers he'd dispatched and unapologetically proclaiming, "I am the Greatest of all time!"

He was introduced to America during those 1960 Summer Olympics, in the waning hours of the Eisenhower era, a time when athletic vainglory was intensely frowned upon, particularly if it emanated from a "Negro" athlete. Ali repeatedly declared that he was pretty—and he was. He said he was gonna "whup" whomever he fought—and he did. As early as 1964, before his first heavyweight title bout, versus Sonny Liston, he proclaimed himself "the Greatest." And he was.

Outspoken and untamable, Ali rocked everyone who dared meet him inside the ring—he won his first 31 pro bouts before succumbing to Frazier in 1971—and anyone who dared to do so outside it. He was equally at ease releasing a flurry of jabs with his fists or his tongue.

Listen to Ali, armed with only a high school diploma, in 1967, as he refused induction into the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War and went toe to toe with a group of white college students: "I'm not gonna help nobody get something my Negroes don't have. If I'm gonna die, I'm gonna die right now, right here, fightin' you. If I'm gonna die. You my enemy. My enemy's the white people, not the Viet Cong…. You my opposer when I want freedom. You my opposer when I want justice. You my opposer when I want equality. You won't even stand up for me in America for my religious beliefs, and you want me to go somewhere and fight, but you won't even stand up for me here at home."

(Ali was also, as an aside, the nation's first rap star. Soon after turning pro by signing with a consortium of white millionaires from his hometown of Louisville, Kentucky, Ali explained, "They got the complexions and connections to give me good directions." He described his MO in a couplet, "Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee," and later in his career branded his bouts with a flourish, e.g. "The Rumble in the Jungle" and "The Thrilla in Manila." No one ever made boxing less grim or more poetic.)

In 1967, Ali was stripped of his heavyweight title and banned from boxing because of his refusal to be inducted into the armed services. He lost three years in the prime of his career when he decided not to fight for his country, a somewhat ironic happenstance, since seven years earlier, at the Olympics in Rome, he had done just that. And at those Olympics, when a reporter suggested to him that America was the land of intolerance, he replied, "Oh yeah, we've got some problems, but get this straight: It's still the best country in the world."

As a child of the 1970s, I worshipped Ali even though I was neither black nor much of a fighter. With his perfectly sculpted 6-foot-3 physique, that majestic countenance and those expressive eyes, he came across as more of a comic book superhero than a boxer to my friends and me ("the black Superman," as a popular song of the time labeled him). In those ABC Wide World of Sports interviews with Howard Cosell, his verbal sparring partner, Ali was playful and mischievous and always entertaining. (Cosell: "You're being extremely truculent." Ali: "Whatever truculent means, if that's good, then I'm that.")

My friends and I never thought of Ali as white or black; we just thought of him as unbeatable. Then he lost. The first defeat came to Frazier in March of 1971, only his third fight back following the three-year hiatus, a 15-rounder at Madison Square Garden. Two years later, in San Diego, he lost again. Ali entered the ring wearing a rhinestone robe, a gift from Elvis Presley, and left with a broken jaw, a gift from Ken Norton. He fought the final two rounds of the bout with the fractured mandible.

Ali's greatest moment in the ring was still ahead of him. He was 32 and no longer as quick or graceful as he had been when he stepped into the ring in Zaire against George Foreman, 25. A 6-foot-4 beast, Foreman was unbeaten (40-0) and in the previous two years had disposed of both Frazier and Norton in less than two rounds. The Greatest was finally the true underdog; he had at last met someone bigger, stronger and younger than he. But not smarter.

In the Rumble in the Jungle, which began at 4 a.m. local time to accommodate pay-per-view American audiences, Ali introduced his "rope-a-dope" strategy, allowing Foreman to pin him against the ropes and exhaust himself throwing punch after punch after punch. Ali tucked himself into the ropes, protecting his face with his 8-ounce Everlast gloves as he patiently waited Foreman out in the simmering jungle heat and humidity.

"Maybe this could be the tactic of Ali," said ringside announcer Bob Sheridan with 30 seconds remaining in the eighth round, "to let the man punch himself out." Ten seconds later, Ali connected on "a sneaky right hand." Eight seconds after that, Foreman was on the canvas.

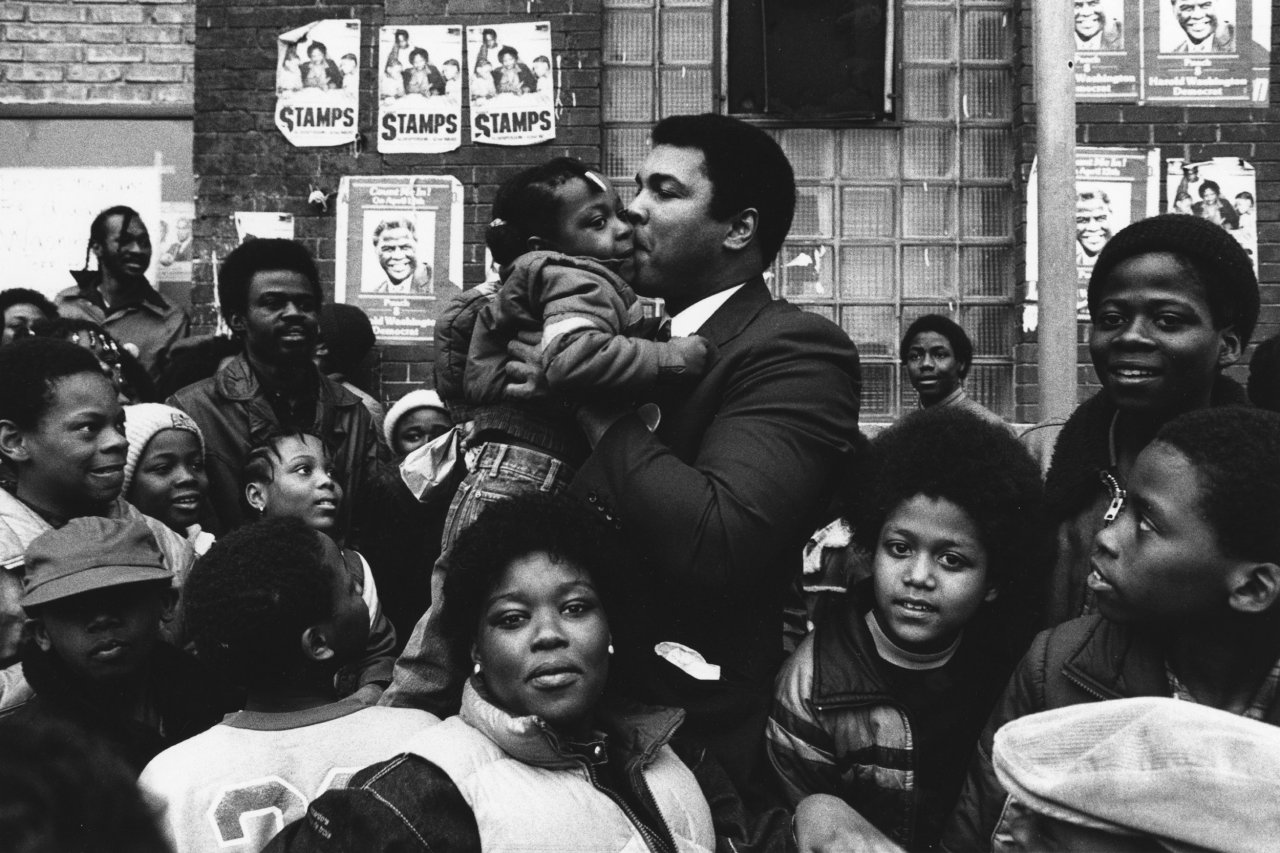

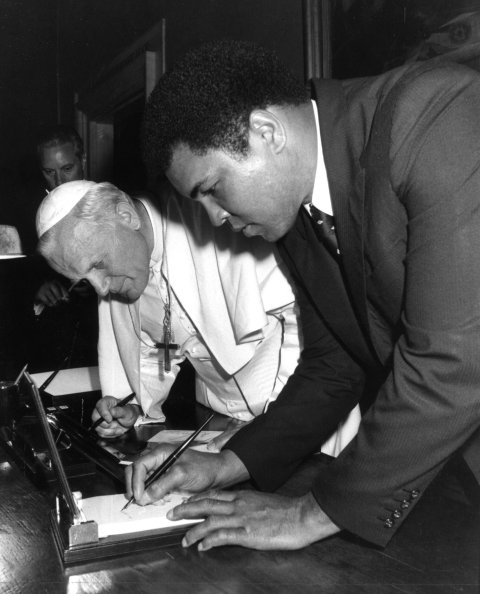

There would be more fights, more purses and even one more colossal victory (versus Frazier in the Philippines), but Ali's final opponent was Parkinson's. He was diagnosed in 1984, and it slowly and cruelly robbed him of his physical abilities and later his ability to speak. In these last 32 years, though, Ali became, as The New York Times called him, a "secular saint," an international ambassador of goodwill.

In Ali's adopted home state of Arizona, where he resided for the last 20 years of his life, he partnered with a few local philanthropists to host an annual event, Fight Night, which has raised more than $100 million for the fight against Parkinson's. In Phoenix, the Muhammad Ali Parkinson Center is at the forefront in terms of research and therapy in battling the crippling neurological disease, for which there is no cure.

Ali's legacy transcends every sport, every geopolitical border and every language. He was a creature immune to self-doubt and a fighter who seemed to embrace, or at least enthrall, every person he met. Immediately after knocking out Liston in February of 1964 to win his first heavyweight title, Ali stepped to a microphone in the ring and repeatedly declared, "I shook up the world!"

That he did. And a world that needed shaking is in his debt.