To be a great hotel is to host fabulous lives but also, sometimes, spectacular deaths. One of these took place on July 26, 1938, when a young man from Long Island named John William Warde climbed out of a 17th-story window of what was then called the Gotham Hotel, in midtown Manhattan, near the southern border of Central Park. He spent the next 11 hours on the 18-inch ledge. "As if it were the afternoon of the crucial game of a World Series, people all over New York gathered around the radios of parked cars" to learn of whether the troubled young man would jump, according to Joel Sayre's account in The New Yorker, "The Man on the Ledge."

Warde's sister, who had been in the room, tried to coax him back inside: "Come in and have a drink, John, darling." Doctors tried to give him Benzedrine. A clergyman showed up from St. Patrick's Cathedral, only to discover that Warde was an Episcopalian. "I have made up my mind," Warde announced. He had tried suicide before. This time, his resolve held. "A priest sprang forward to administer last rites," Sayre wrote, "but John was beyond that."

On the evening of February 3, 2010, Gigi B. Jordan checked into the same hotel, which was now called the Peninsula. She asked for a suite: $2,500 a night. She paid in cash. Before arriving at the Peninsula, Jordan, who had started a successful home health care company 20 years earlier, had gone to a Chase Bank, where she made a transfer of $8 million between two accounts. Then she got into a taxi and had it drive around Manhattan for three hours, in the midst of rush hour: an expensive exercise in aimlessness. She thought about going to the Mercer Hotel, in SoHo, and the Sofitel, in Times Square. Finally, she decided on the Peninsula. After settling with the front desk, she took the elevator to the 16th floor and entered Room 1603, a sumptuous suite of cream colors and dark wood finishes. Except for quick dealings with hotel staff conducted in the doorway, she would not leave the room for the next 40 hours.

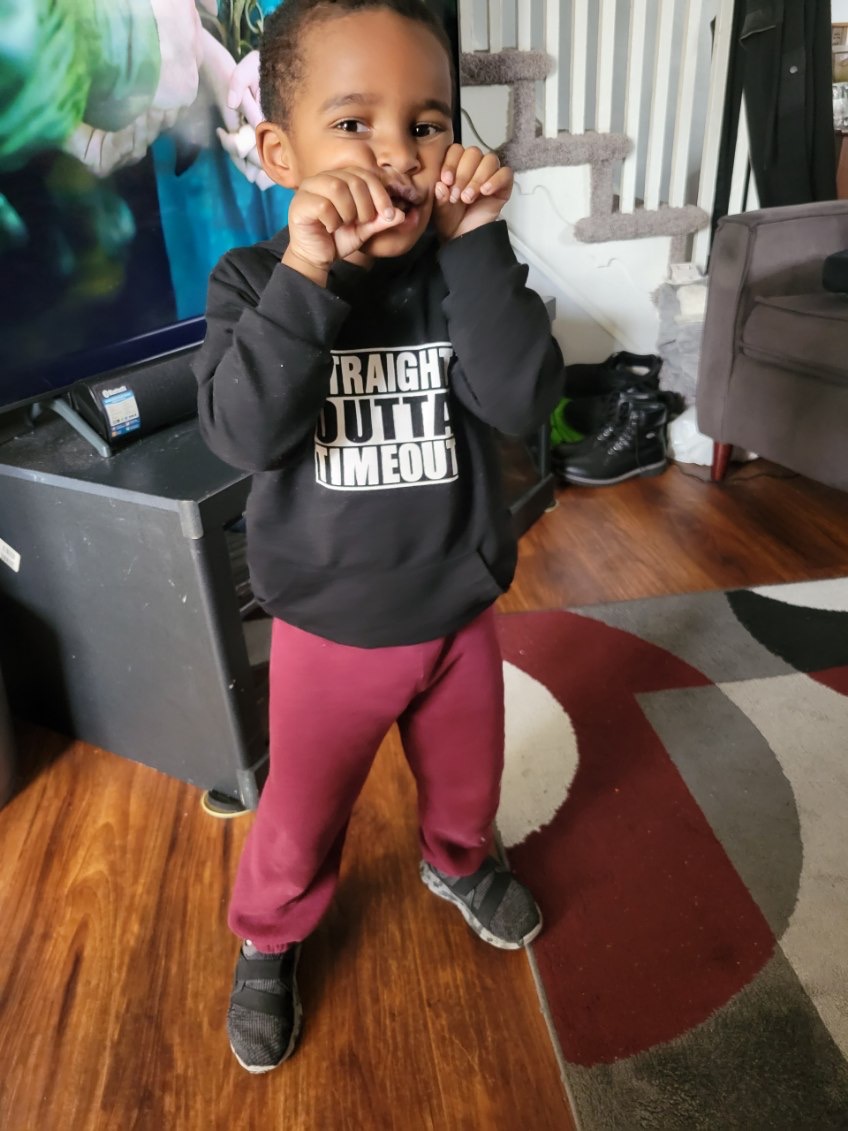

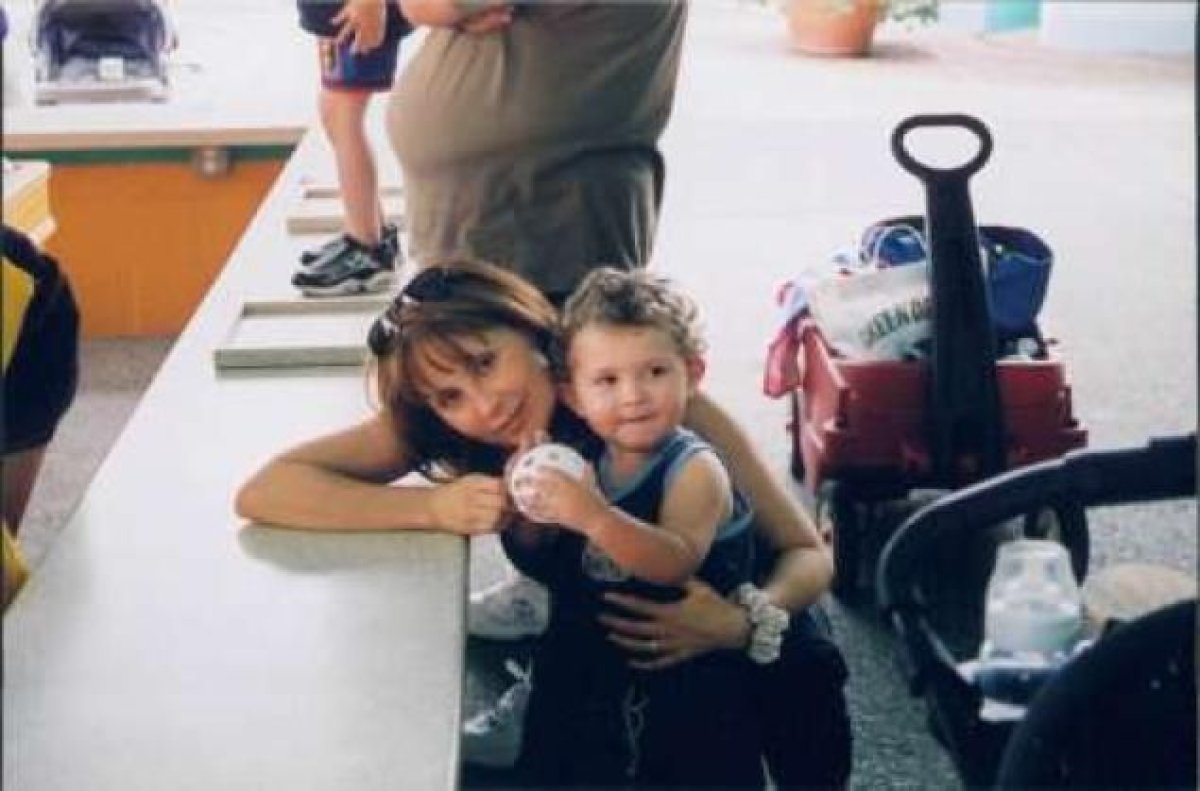

Jordan was not alone. With her was her son, Jude Michael Mirra. Jude was born on July 13, 2001, to Jordan and a Bulgarian yoga instructor named Emil Tzekov, whom she met at a gym where they both exercised. Jude seemed to develop normally at first: One photograph shows him with his parents, curly-haired, smiling. Like his mother, he had cheeks so full they seem to billow toward his eyes, narrowing them. But when he was 2 years old, Jude was diagnosed with autism, a disorder marked by poor social skills, a lack of communication and repetitive behaviors. Many autistics can, with therapy and medication, live lives that have all the meaning and mundanity of a "normal" existence. Some cannot. Jude appeared to be heading for the latter category.

Little is known about what causes autism. Even less is known about what might halt its ravages. Some antidepressants and antipsychotics can alleviate symptoms. So can, intriguingly but only briefly, high fevers. But there is no silver bullet, nor a target at which to fire one, since autism's locus in the brain is yet another of that disorder's myriad unknowns.

That has allowed the ignorant and the unscrupulous to hawk curative therapies, exploiting the dwindling hopes of parents whose children may sleep only an hour or two a night, may have no bowel control, may lack the language to express their inner or outer torments. Children who will never attend college or hold a job, marry or live alone.

Some of these treatments, like a gluten-free diet, are harmless enough. Others, like chelation therapy (the extraction of heavy metals from the body) have killed some of those they promised to save.

Nothing Jordan tried worked, and she had the money to try just about everything. Her life hopscotched between some of the most affluent ZIP codes in the United States: in Marin County, Manhattan, Lake Tahoe, the horse country of Virginia. Yet her wealth proved a burden of its own, allowing her to shuttle Jude from one expert to another, from failed promises of salvation to those that would surely be realized.

In early 2008, Jordan started to unravel. She became increasingly convinced Jude was trying to tell her that he had been sexually abused and tortured. With his inchoate language, and with the supposed help of a laptop, Jude told his mother of nearly two dozen other people who participated in sexual transgressions against him. The list included his biological father, Tzekov; other members of the Tzekov family; and various caretakers, as well as Raymond A. Mirra, her second husband. The gruesome trespasses included sex and violence, feces and blood, toddler girls, the carcasses of dogs, a procession worthy of the Marquis de Sade.

Jordan began corresponding with Flint Waters, a Wyoming-based investigator of Internet crimes against children. Eventually, she took Jude to Cheyenne, hoping that he could tell Waters about the abuse he'd suffered. But at the Cheyenne Regional Airport, agents from Wyoming's Division of Criminal Investigation were waiting for Jordan. The story she told them, rife with molesters and "satanic cults" (a reference to a disconcerting photograph a caretaker for Jude had posted on her MySpace page) troubled these authorities, though not quite in the intended way. Jordan was taken to the Cheyenne Regional Medical Center and held there for several days, while Jude was put into foster care.

Calls from Jordan's friends eventually won her release, and Jude returned with her to California. But the episode only fired her conviction that forces were aligning against her. Tzekov was but part of the story; Jordan also started to think that Mirra had stolen millions of dollars from her and was planning to have her killed by his associates from Philadelphia's organized crime syndicate. Her death would return Jude to Tzekov's clutches. Of this, she claims she was certain.

In 2009, Jordan enrolled Jude in the small and progressive Studio School, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan (she never seemed to stay in a single place for more than a month). Many autistic children cannot cope with a traditional classroom setting: Their uncompromisingly regimented behaviors, inability to speak and reluctance to follow instruction make "mainstreamed" schooling a nearly insurmountable challenge for everyone involved. But the Studio School seemed like the kind of small, caring place where Jude could thrive. He appeared to take to Julianne Mabey, who taught the middle grades. If Jude refused to come into the classroom, Mabey allowed him to sit out in the hallway, in his favorite rocking chair.

In December, a breakthrough: Jude spoke. It was a single word, "Hi," but Mabey would remember it very clearly as a "thrilling" moment. She thought Jude was emerging, finally. Once, he went ice skating with the other children in Central Park. Jude could not skate, but he seemed to watch his classmates intently, with what might have been curiosity or even longing. At one point, he chose to sit next to another teacher, instead of with his mother. "That was an exciting moment for those us watching and observing," Mabey later said, "every time Jude was making contact with somebody and moving away from his mother physically."

Mabey last saw Jude on January 19, 2010. Eleven days later, Jordan took Jude to Florida. They stayed at the Four Seasons in Palm Beach, returning to New York on February 3. Jordan had an apartment in the Trump International Hotel & Tower, at Columbus Circle, which had an intricate series of locks to prevent entrance by Mirra and his henchmen. She and Jude went into the apartment and emerged about five minutes later. Next, they went to the corner of 72nd Street and Columbus Avenue, where Jordan bought Jude a hot dog. Then she went into a Chase branch and made the $8 million transfer.

They got into a cab and rode around for about two hours and 45 minutes. Some of this time was spent looking for a hotel, but much of it was aimless wandering. Jordan already knew she was going to kill Jude, because he was autistic, or because he was the victim of trauma from which he could never recover, or because he had told her he wanted to die. "Gigi Jordan saw no path by which she could protect her child," a 2011 bail application filed on her behalf declared. "Death—for both of them—was the only refuge."

The evening traffic eased, the city settling into wintry repose. At about 8 p.m., the cab delivered Jude and Jordan to the graceful front entrance of the Peninsula Hotel.

There are four basic things we want to know about every illness: what causes it, how it advances, how we can stop that advance and what we can do to prevent others from getting sick in the first place. Autism is a mystery on each of these counts. Many illnesses today have an awareness ribbon, most famous among them the pink one for breast cancer. The ribbon for autism is multicolored puzzle pieces.

Many of those pieces we simply don't have, never mind knowing how they fit together. Hundreds of genetic variations that are likely responsible for different types of autism remain unknown, eluding our increasingly powerful DNA sequencing tools. We do not know what autism does to the brain, why many autistic children have seizures, why some have anxiety and obsessive-compulsive symptoms. Many autistic children have weak immune systems and gastrointestinal problems—two more mysteries. There are many more autistic boys than girls, and there seem to be many more autistic children today than there were 30 years ago. About this, too, we are puzzled. We don't even know how many people in the United States have autism: The most commonly cited statistic is the determination by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) that, as of 2010, one in 68 American children was being diagnosed with autism spectrum disorder.

And, like a puzzle, autism consists of incongruent pieces. The diagnosis can capture a dismayingly broad swath of human behavior. I have met a 12-year-old autistic boy who told me he wanted to be an announcer for the Yankees; when I asked if the Mets would do, he scoffed at the suggestion, just as any rational person would. I have watched an older teenage boy rock and moan during a sing-along, folding and unfolding with such violence, he seemed about to fall out of his folding chair. I have watched a teacher trying to coax a greeting from a child, only to receive a reluctant moan in return. I have listened to autistic children confidently declaim about Pablo Picasso and the Mesozoic Era.

There should be a neat paragraph here describing what autism is, but that would be impossible to write. The more you know about autism, the less you are able to say with confidence. According to the fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, autism spectrum disorder encompasses everything from what used to be known as Asperger's disorder, applied to higher-functioning autistics with normal language development and intellectual ability but a lack of social skills, to severe cases branded as mental retardation in the past. There is no pervasive biological abnormality that renders one autistic. There is only the observable behavior: the silence, the stereotypic movements like hand flapping (known as stimming), the inexplicable fixations, the lack of sleep, the stomach pains. A diagnosis of autism is subjective, damning and opaque. Often, it only confirms what the parents already fear.

The politics of autism is balkanized, too. Some higher-functioning autism activists tout "neurodiversity," wanting to see themselves as a maligned minority, not a cohort of patients to be manipulated by Big Pharma. Autism is a gift, not a disease, they proclaim. Do you value the insights of Einstein or the compositions of Mozart? Thank autism, they say.

And then there is the anti-vaccine crowd, which hijacked the autism debate for much of the early aughts. Their campaign began in 1998, when the British gastroenterologist Andrew Wakefield published a paper in The Lancet titled "Ileal-lymphoid-nodular hyperplasia, non-specific colitis, and pervasive developmental disorder in children." The title was inscrutable; the findings, remarkable. Wakefield was effectively asserting that the measles, mumps and rubella (MMR) vaccine caused autism. Parents embraced Wakefield's "discovery," and untold millions have been spent searching for a definitive link between vaccines and autism. No such link has been found, and, in 2010, The Lancet retracted Wakefield's paper, noting that critical components were "incorrect" and "false."

Alison Singer should have been as prepared for the diagnosis as any parent, for she had seen it before. In 1968, when Singer was 2, her older brother Steven was diagnosed with autism. "Back then, there were no services at all," she told me when we met at a diner in Scarsdale, New York. "There was nothing." He was put in an institution called the Willowbrook State School, on Staten Island, which doctors told Singer's mother "was the best place for him." But Willowbrook was a warehouse of suffering, cowering children. In 1972 (by which time Steven had already been moved to another institution), a young investigative reporter decided to take a close look at the "big place with a pretty-sounding name." The resulting documentary, Willowbrook: the Last Great Disgrace, earned Geraldo Rivera a Peabody Award.

Singer, who now runs the Autism Science Foundation, went to Yale and got a job at NBC, where she rose to the position of vice president. Her first child was born in 1997: a daughter, Jodie. Looking back, she thinks she should have seen at once that something was amiss. "Jodie had unusual behaviors from birth," Singer told me. "She didn't eat, she didn't sleep, she didn't nurse. She cried constantly." Jodie had echolalic language, a common feature of autism: She could repeat back, with great accuracy, things she had heard, but she could not use her own words to communicate. The diagnosis of autism came when Jodie was 2 years, 8 months old.

Jodie developed with what Singer called "minimal language" and "self-injurious, aggressive behaviors." Her younger daughter, Lauren, did not develop autism. In 2006, Singer starred in a short documentary called Autism Every Day, produced by the advocacy group Autism Speaks, for which she was working at the time. As Jodie plays in the background, Singer looks into the camera and admits to once having "contemplated putting Jodie in the car and driving off the George Washington Bridge" instead of sending her to a school that, while not Willowbrook, could never adequately care for her.

After many difficult years, Singer managed to place Jodie at the Center for Discovery, a teaching farm for autistic children in upstate New York. "She has never been happier," Singer says.

But the mystery of Jodie's autism remains. Because Singer's brother and daughter are autistic, one could reasonably conclude that Singer's family has a genetic susceptibility to autism, much as some families are at greater risk for, say, colon cancer or obesity. Singer had her daughter's DNA sequenced several times and says that "Jodie has the cleanest genome known to man." Known's the key. Rogue strands of DNA may be hiding in that vast array of genomic data. A lot can go wrong in the 20,000 genes carried by a single human. And the problem may not be with the structure of genes but with how those genes are expressed, a field known as epigenetics.

Dr. Gerald D. Fischbach, the chief scientist at the Simons Foundation in New York, says he knows of a little more than a dozen gene variations that seem to recur in children with autism. He estimates that, ultimately, there were will be 300 to 500 genetic variations associated with autism. Others put the number at 1,000.

"Everybody thought this was going to be the great hope," says Dr. Robert L. Hendren, the vice chair of psychiatry at the University of California at San Francisco School of Medicine. "We'd just find the gene or genes and then we'd have autism figured out." That promise, suggested by the Human Genome Project, has not yet been realized. And even when we know which genes are responsible for autism, we won't entirely know what to do with that information. "Switching them on and off like a switchboard," Hendren says, "I think it would be very difficult, and very controversial."

The case of Huntington's disease has been instructive. We know the culprit: a single gene on chromosome 4, located at 4p16.3. We've known that since 1993, yet this hard-won knowledge hasn't yielded a cure, because the pathway from chromosome 4 to being unable to brush your own teeth at the age of 45 is enormously long and complex. And autism, we already know, is not a single-gene disorder like Huntington's.

Nor do genes fully account for the incidence of autism. Most scientists think environmental factors play an insidious role. Dr. Irva Hertz-Picciotto, an environmental epidemiologist at the University of California at Davis, told me that she thinks the breakdown is about 50-50 between the genome and external triggers. That suggests a two-hit theory similar to that governing cancer: genetic disposition coupled with malevolent influences. But autism researchers don't know the genes or the triggers.

"It's not gonna be a quick win," warns Dr. Wendy K. Chung, a molecular geneticist at Columbia University Medical Center.

"I felt numb, defeated," Jordan later recalled as she and Jude entered the Peninsula on the evening of February 3, 2010. "I felt like it was over, done." She was certain Ray Mirra's goons were coming after her and her son. After they killed her, Jude would be returned to Emil Tzekov, his father, who would molest the disabled boy. "He still wasn't safe, and I still couldn't protect him," Jordan would remember more than four years after that winter night.

Jordan and Jude left the front desk and went up to the 16th floor, checking into Room 1603 at 8:08 p.m. What they did for the next 40 hours is unclear, even to Jordan: "I wasn't aware of time at all." Others have pieced together some of what transpired. Several minutes after checking in, Jordan called room service and a waiter brought chicken fingers and carrots, which were to presumably serve as Jude's dinner. He also brought a bucket of ice, likely for the bottle of Grey Goose that Jordan had carried into the hotel inside her bags. Also in her bags were about 6,000 pills (5,819 would eventually be recovered): Xanax, Prozac, Ambien, Catapres, Celebrex, Asacol, Naltrexone and hydrocodone. The vast majority of these had been legally prescribed for Jude, who took about 40 pills per day. Jordan also had a pill crusher. And a syringe.

Jordan says she and Jude spent the evening "saying goodbye to each other." Jude watched a movie.

Around midnight, Jordan gave Jude about 20 pills of Xanax and 40 pills of Ambien. No child is supposed to take this many pills, or to wash them down with vodka. After he fell asleep, the prosecution alleges that Jordan crushed a fresh helping of pills into the vodka-and-orange juice solution she'd been drinking. She then allegedly got on top of him and forced the "murderous concoction" into his mouth, "using enough force to bruise that boy on the face, the nose, the chest."

It was now the very early morning of February 4, 2010. At some point during the hours that followed, Jordan wrote checks to two charities: Doctors Without Borders and the Red Cross relief fund for victims of the recent earthquake in Haiti. A hotel employee named Ivy Chen came up to collect the letters from her. Jordan also called down to the front desk to say that she would be staying for another night, and the night manager, Samir Ibrahim, came up to collect payment ($1,000). Another employee delivered the bottle of water she had requested.

Little is known about the rest of Thursday. But on Friday at 1:53 a.m., Jordan sent an email to her accountant instructing that $125,000 be moved from a trust for Jude into one of her accounts. She continues to maintain it was a routine transaction, ordered by a woman nearly gone from this world; prosecutors say it is revealing of her heartlessness. They wonder, too, why a woman about to take her own life would bother to balance a checkbook.

In the hours after drugging Jude, Jordan composed what has been described as a "rambling 20-page message," a summary of the cruel fate that had befallen her and Jude. Eventually, she sent this as an email to an aunt traveling through Europe. When the aunt read it, she understood what had transpired and called the Trump. The Trump called the Peninsula. A security manager, Christopher Nguyen, took the call. He was informed that officers from the New York Police Department were about to pay the Peninsula a visit. Four of them soon arrived. Nguyen took them up to Room 1603. He unlocked the door with a master key. It was blocked by a chair. They pushed the chair aside. Pill bottles were everywhere, as if a grim party had just concluded. "The light was on but dim," Nguyen testified. "Ms. Jordan was sitting on the floor leaning against the bed." In the bed, there was a boy who must have looked like he was sleeping.

Jordan thus joined a small, ignominious league of mothers who kill their autistic children (if fathers do so less frequently, it is probably because they are less frequently saddled with the caretaking). In the fall of 2014, as Jordan finally went to trial on murder charges, her story was overshadowed in the national media by that of Kelli Stapleton, a 46-year-old Michigan woman who tried to kill her autistic daughter Isabelle and herself by lighting charcoal grills inside a minivan. The daughter survived; the mother is facing attempted murder charges. In an interview with Dr. Phil, the television personality, Stapleton said, "The jail of Benzie County has been a much kinder warden than the jail of autism has been."

In Far From the Tree: Parents, Children and the Search for Identity, Andrew Solomon lists many cases that resemble those of Jordan and Stapleton. He concludes that "the habit of the courts has been to treat filicide as an understandable, if unfortunate, result of the strains of raising an autistic child. Sentences are light, and both the courtroom and the press frequently accept the murderer's profession of altruistic motives."

That Gigi Jordan killed her son was never in dispute. Like Stapleton, she tried, and failed, in also taking her own life. When the cops burst into her room, shortly before noon on February 4, 2010, her first words to them were, allegedly, "I want a lawyer." She would later claim that she had sought to kill herself, too, but failed. Prosecutors have openly wondered if Jordan's attempt at self-slaughter was less earnest than the procedure that took her son.

Of course, very few parents of autistic children ever contemplate or commit murder. "Many parents with autism are doing a really good job," says Simon Baron-Cohen, the prominent University of Cambridge autism researcher. He warns that an un-nuanced focus by the media on autism-related filicide harks back to the 1950s, when the "refrigerator mother" theory of autism erroneously suggested that a lack of maternal affection caused autism.

Nor is it helpful to describe all autistic children as helpless souls fated to misery. Many children with autism can live with some measure of comfort in the world, and CDC data suggest 46 percent of autistic children have either average or above-average intelligence.

Baron-Cohen, who was not familiar with the Jordan case before I sent him media reports of the trial, speculates that Jordan's actions on the night of February 3, 2010, were "close to a cry for help." That cry was needlessly savage, as much a reflection of Jordan's troubled psychology as of Jude's private torments.

"This is not hopeless," says Dr. Louis F. Reichardt, director of the Simons Foundation Autism Research Initiative, referring to recent advances in understanding autism's origins. And, he notes, behavioral therapy can exploit the brain's inherent plasticity to teach social behaviors.

"Attitudes of caregivers towards their kids make a huge positive or negative difference," Reichardt told me. Those caregivers are, often, women on their own.

"Many of the fathers of the autistic kids I know have moved on," writes Hannah Brown, the mother of an autistic teenager. "They have new lives. Often, they have new kids." Her ex- helps pay the bills, but she is fundamentally alone, as Jordan was for much of Jude's life.

All science starts as bad science. Humors course through the body; stars and planets circle the Earth. Some of what we call truth today, others will in time condemn as heresy. What is mysterious to us will be obvious to them. Future generations may well laugh at our debate over global warming, our blithe consumption of red meat, or diet soda, or gluten, or something else.

The human species loves origin stories. Autism, thus far, lacks one. But Judy van de Water thinks she might have an answer. Not the answer, mind you, but an answer, since a single scheme for all of autism is as unlikely as a single scheme for all of cancer. Those who yearn for neat explanations best look elsewhere, for the complexity of autism has laid to waste to many a packed conference hall and optimistic PowerPoint presentation.

Van de Water's office at the University of California at Davis looks out over the flat expanse of the Sacramento Valley, jaundiced by drought. In the distance, some cinereous serrations indicate the Diablo Range, which obscures the California coast. From here, the Pacific Ocean seems impossibly distant.

This has been van de Water's view, more or less, for the past four decades. She was born in Muncie, Indiana, in 1955; her family moved to Menlo Park, California, near Palo Alto, in 1970. Her entire career, as both a student and a scientist, has been spent at UC Davis. She got her doctorate from that school, in immunology, in 1988. Much of her early work was on skin and liver disorders.

In 1998, six Sacramento-area families with severely autistic children started what would become the UC Davis MIND Institute, today housed at the university's medical campus in nearby Sacramento. At its inception, MIND's founders were "fired up" about Wakefield's study, van de Water says, and while that would prove a fruitless path of investigation, the impetus to look at autism as more than just a collection of behaviors has remained, attracting researchers from outside neurology, like van de Water, to the field.

There had been promising work into the relationship between the immune system and neurological disorders by Reed P. Warren, an immunologist at Utah State University who in 1986 published a paper titled "Immune abnormalities in patients with autism." The following year, he published "Reduced natural killer cell activity in autism" (natural killer cells also figure prominently in cancer research). But the focus eventually turned to behavior, and the neuroimmunological research "petered out," says van de Water. For all the harm it caused, Wakefield's infamous paper did return attention—at great cost—to the potential relationship between immune dysregulation and brain dysfunction. (Warren died of kidney cancer the same year Wakefield published his paper on the MMR vaccine.) "People started thinking about the immune system again," van de Water says, hastening to add that Wakefield's study was "irresponsible" in many respects.

In 1999, van de Water got a pilot grant to study the immune-autism link. She says she found nothing of significance related to vaccines themselves, "but we did start noticing immune anomalies in the kids. And then it just snowballed." She and a colleague, Paul Ashwood, discovered that many autistic children had a deficit of a cytokine called Transforming Growth Factor Beta, a signaling protein in the immune system. Other autistic children had an excess of inflammatory cytokines. This seemed to hark back to the largely forgotten work done by Warren at Utah State.

Van de Water estimates that perhaps as many as half of all autistic children have "some immune anomaly." Stray cytokines and immune cells, then, could serve as early postnatal warning signs that autism lays in wait. Researchers have long searched for a biomarker that indicated a susceptibility to autism—much as, for example, a PSA test looks for a certain antigen in the blood to indicate the presence of prostate cancer. Without biomarkers, we wait for autism to announce itself with behavior symptoms. An earlier, more definitive warning could give parents time to prepare and begin the kind of intensive behavior therapy that can ameliorate the severity of symptoms.

Right after a child is born, it undergoes a heelstick blood test for phenylketonuria, sickle-cell disease and other disorders. Earlier this year, van de Water and other researchers published an article in the Journal of Neuroinflammation that looked at the neonatal heelsticks of children who were later determined to either have autism, some other development disorder or no disorder at all. Most of the neonatal blood had no detectable cytokines at all—a disappointing result. Nevertheless, autistic children did have high levels of a chemokine called MCP-1. Van de Water says that more recent research into cytokines, not yet published, suggests a "very distinct pattern" she hadn't seen before. "I'm excited by these data," she says. "This would be an early, early indicator."

Jude Michael Mirra was diagnosed with autism while van de Water was in the early stages of research into autism's roots in the immune system. Gigi Jordan came to believe Jude's autism was related to immune dysfunction, and some of his doctors agreed. "It seems apparent that Jude's autism is somehow related to an neuro-immune response," wrote the Manhattan-based pediatric neurologist A. Maurine Packard in 2005. (Packard refused to comment for this article; repeated requests to visit Jordan at Rikers Island were also rebuffed.) In fact, van de Water was one of the clinicians Jordan consulted about a stem-cell treatment for Jude. Van de Water never met either the mother or the son, but remembers the case well. She says that Jordan even invited her to a holiday party in Manhattan. Van de Water didn't go.

But finding an immune biomarker, even one present at birth, isn't the same as unraveling the mechanism that gives rise to autism. In 2003, the researcher Paola Dalton published a study in which rats were injected with serum antibodies from the mother of an autistic child. The rat then gave birth to pinkies that showed behaviors suggesting autism. A postdoctoral student of van de Water's thought there was unrealized promise here. "They never did anything else with it," van de Water says of the Dalton study. "It sort of seemed like a natural thing to pursue."

Van de Water pursued the lead for the next several years, eventually coming to a conclusion that was both promising and troubling. In about a quarter of all cases of autism (she studied a cohort of 246), immunoglobulin antibodies from the mother were attacking fetal brain cells, causing changes in neuronal development in the unborn child. Why the attack was happening she could not say, but the overly aggressive antibodies were meeting little resistance, since the fetus does not yet have a solidly formed blood-brain barrier that more or less walls off the central nervous system from the circulatory one.

Van de Water injected the maternal antibodies into monkeys, then into mice. With Jacqueline N. Crawley, a pioneer in mouse models of autism who wrote a book called What's Wrong With My Mouse?, we we watched videos of mice very similar to those that Van de Water had used. Crawley sternly warned me not to ever call the rodents on the screen "autistic mice." But it is impossible to call them anything else. They groomed obsessively, engaging in the kind of repetitive behavior that is a hallmark of autism. And given the choice to play either alone or with another mouse, they chose the former—a telling, damning solipsism that any parent of an autistic child will recognize at once.

The monkeys were worse, their symptoms so closely approximating human autism that it was impossible for me to watch them without experiencing extreme anxiety. One refused to recognize its mother, pacing its cage in a route from which it never deviated. Another did backflip after backflip, frightening its cage-mate. These animals were obviously, viscerally sick.

Van de Water's findings, published in 2013, were not well received. Science magazine published an article titled "Alarm Over Autism Test," questioning the predictive quality of the maternal antibody test. It did not help that van de Water had licensed her test to a Sacramento firm called Pediatric Bioscience, leading to accusations of commercialism. "They're overstating what they have," Yale researcher George Anderson told Science, "and they're proceeding too quickly. You don't need to commercialize something to make it available as a research tool."

Van de Water is dismayed by these accusations. "The math was fine for the study," she asserts, suggesting that her scope was more modest than what the press subsequently described. "They didn't really read the paper carefully," she says of her critics, including two science journalists for Forbes, Steven Salzberg and Emily Willingham, who seemed to take particular relish in dismantling the maternal antibody findings, the former accusing van de Water of "cashing in" on her work. They are as vehement in their convictions as van de Water is in hers.

Most galling to van de Water is the notion—which persists to this day—that her maternal antibody test might lead women to abort fetuses at high risk for developing autism. That's what happens with fetuses that test positive for Down Syndrome: More than 90 percent of them are aborted. Van de Water counters that the maternal antibody test should be done before conception, since the guilty antibodies would be just as present in the mother's system then.

But even if there is soon a widely used maternal antibody test for autism—and that if is roughly the size of California—it will account for only some portion of the risk for some portion of the population (about 23 percent, according to current estimates). Many of van de Water's colleagues, as well as researchers across the nation, are trying to fill in the rest of the puzzle, some trying to decode the genome, others trying to discern which environmental factors might be at risk.

Not all that long ago, to even utter the phrase "environmental causes of autism" was to declare yourself in Wakefield's camp, for vaccines crowded out any other actors in the epidemiological stage. That is no longer the case. Responsible investigations into this field could well inform public health. True, things may never be as clear as Avoid X, Y and Z if you want to prevent autism, but we may finally know what risk factors exacerbate dormant genetic predispositions. (Here, again, autism research would be following in the well-trod path of oncology.)

Those risk factors are starting to emerge. Hertz-Picciotto, the MIND epidemiologist, recently published a study suggesting that pregnant women who were exposed to pesticides had a higher chance of giving birth to autistic children. When I met her, Hertz-Picciotto listed a number of other potential risk factors: plasticisers like bisphenol-A and phthalates, flame retardants, maternal age, paternal age, obesity.

"There is not one autism," says Dr. Isaac S. Kohane, a neuroinformatics expert at Harvard. "There are multiple autisms," he believes, each with its distinct causes. Kohane recently published a study that examined the health records of 14,381 people, in search of autism's co-morbidities. These included epilepsy (20 percent) and gastrointestinal problems (12 percent), suggesting the staggering diversity of the disorder. "I'm quite sure autism is going to augment into different diseases," Kohane says. Many (though certainly not all) researchers share the same conviction. And each sub-species of autism will need its own researchers like van de Water, willing to pursue the disorder through the tangles of the genome, the central nervous system and, maybe, beyond.

Gigi Jordan was born in Manhattan and grew up on the Upper West Side. Her parents divorced when she was 5½ years old. She had a sister, who went to live with her father in Southern California. In 1973, she moved with her mother to the Bay Area. She first married at 17, to a man about twice her age who was living with a friend of hers. The friendship did not last. Neither did the marriage.

During the 1980s, Jordan worked as a nurse at hospitals in San Francisco, including the Langley Porter Psychiatric Institute, a maroon Art Deco building on the campus of the University of California at San Francisco. I recently visited the place, though not to see about Jordan. Here, many years after Jordan left, fruitful research in autism has taken hold.

Hendren arrived at UCSF in 2009. For the previous eight years, he had been the head of the MIND Institute in Davis, living there in a studio apartment several days each week while his wife, who is French, remained in Marin County, much closer to San Francisco. Eventually, that separation proved too taxing, and Hendren traded the baking heat of Davis for the pearly fog of Parnassus Heights. Today, he is the vice chairman of psychiatry at the UCSF School of Medicine and heads the child psychiatry program there.

Hendren, who is in his 60s, has perfect hair and perfect suits, blue eyes and tanned skin. He looks like an actor happily past his prime, enjoying the good life in Malibu. He thinks like his old MIND Institute colleagues, drawn to the promisingly unconventional.

In keeping with the Northern California ethos, Hendren showed me what he calls the "terroir" model of autism, a reference to the delicate soil conditions winemakers say influence every vintage. The bedrock is the DNA itself, the A-G-T-C base pairs that twist into genes and chromosomes, with about 27,000 base pairs making up a single gene. At the very top, growing from the topsoil, are the symptoms themselves, the handful of physical manifestations of unseen processes, of genes silenced or proteins overproduced, neurons that were never pruned, ion channels that don't work quite as they should.

Many are trying to hit bedrock, unraveling the genes responsible for autism. And intensive "topsoil" therapies like Applied Behavior Analysis can, in some cases, teach autistic children to control their symptoms, though the reward-driven philosophy of ABA reminds some discomfortingly of dog training. Hendren is more interested in the stuff in the middle, the layers of soil where the roots of autism draw nourishment.

Many others around the nation are trying this middle-earth approach. What's novel—and risky—about Hendren's work is the focus on complementary and alternative medicine, which he maintains is used by as many as 82 percent of children recently diagnosed with autism, partly because of "concerns with the safety and adverse effects of prescribed medications," as he put it in a recent presentation.

There may be "folk wisdom," Hendren told me, in alternative approaches to autism, deployed by "wise physicians who maybe didn't fully understand the mechanism but had some sense of these things making a difference." Hendren decided that, with his team, he would investigate which of these alternative approaches relied on wisdom, and which were hopelessly mired in illusion.

Hendren acknowledges that some alternative medicine is what he calls "breath of the dragon," quasi-medical shamanism for which "there is no real mechanism that we can think of that somehow makes a difference." Prime among these is chelation therapy, a leaching of heavy metals from the body. The approach is popular with anti-vaccine advocates who believe that a mercury preservative, thimerosal, is responsible for autism. Chelation therapy is dangerous and unsound, and it has killed children. Hendren discourages parents from using it, yet if they insist, he will send them to someone who will at least perform the procedure I safely. "Come back and see me after you've tried it," he says.

Other treatments are both less dangerous and, perhaps, more promising. One of them is the use of hyperbaric oxygen chambers, long believed by some parents to alleviate the symptoms of autism. In 2012, Hendren published the results of a clinical trial suggesting that these parents may be at least partly correct. The research team observed that in nine out of 10 children who received such treatments, some autism symptoms attenuated. Hendren later told me he thinks the treatment might only work "for a limited number of kids." But even knowing that much would amount to an advance over unverified curative claims.

"We're not gonna come out with some half-baked study," Hendren assures me when I ask if he is afraid his reputation will suffer from this focus on alternative medicine. "I wanna do good science." He thinks, for example, that methyl B-12, melatonin and N-acetylcysteine (an antioxidant agent) treatments may be especially promising. Little risk, or cost, is involved with the use of such supplements by parents. Hendren says that "selected kids" might also benefit from treatments with pancreatic enzymes.

Others also see promise in applying the rigors of science to alternative medicine or folk therapy. In mid-October, The New York Times published an op-ed by the journalist Moises Velasquez-Manoff, who had been investigating disorders of the "gut-brain axis." The article argued that gluten may indeed be responsible for the worsening of some neurological disorders, including possibly autism. Wheat-free diets had long been dismissed as an unscientific fad of the anti-vaccine crowd. If further study bears out, the laughter will subside.

Autism research is so fraught that the mere mention of alternative approaches and immune dysregulation immediately summons up images of Andrew Wakefield. Outside the conventional paths of brain imaging and gene sequencing, things can get thorny.

And they can sometimes get thorny for Hendren. He was asked, before a recent conference, to remove a phrase about altering vaccine schedules from a slide show. He had listed that as a potential risk factor; he took it out, but it was back in when I saw his presentation. The idea isn't preposterous, but hotly contested. And Hendren has endorsed the work of Martha Herbert, an assistant professor of neurology at Harvard associated with the thimerosal theory of autism. When I asked about her work, he called Herbert's argument against thimerosal-based vaccines "well reasoned," but noted that he did not agree with all of her conclusions.

One of the most vociferous opponents of the autism-vaccine link is Dr. Paul A. Offit. Offit comes by his righteous anger honestly: He created the rotavirus vaccine and is perhaps the nation's most prominent defender of mass vaccination. The anti-vaxxers attack him viciously; he hits right back. His books have unsubtle titles like Killing Us Softly: The Sense and Nonsense of Alternative Medicine and Autism's False Prophets: Bad Science, Risky Medicine, and the Search for a Cure. In the former of these, he writes, "Although conventional therapies can be disappointing, alternative therapies shouldn't be given a free pass.... All therapies should be held to the same high standard of proof."

This is what Hendren appears to be doing, playing traffic cop on Cure Autism Highway, where ideas travel at the speed of irrational hope. It seems a largely thankless job, with Hendren at worst standing accused of dabbling in quack medicine. At best, he will only confirm an already extant practice awaiting official imprimatur.

But though the case of Jude Michael Mirra is extreme, it shows just how far parents will venture outside conventional medicine, which they often mistrust when it comes to autism. One letter written on Jude's behalf by a doctor makes clear what's at stake, not just for him but for every child who receives the diagnosis: "There is real concern from all involved in this patient's care that he may end up permanently institutionalized with no hope of employment or meaningful life."

That realization drove Jordan to commit murder. But in far less extreme, far more common cases, parents will spend thousands of dollars on treatments that may turn out to be worthless. Dispelling illusions is often unpleasant, but science demands it.

Gigi Jordan finally took the stand on October 8, 2014, more than four years after she murdered her son. She spent the intervening time on Rikers Island, the island jail where conditions are notoriously grim. Reports from New York's Correctional Health Services, submitted in 2011 as part of an unsuccessful bail application, show her on the mood stabilizer lamotrigine and the anti-anxiety agent clonazepam, among other medications. "I'm fine with my meds," she said on March 22, 2011. The suicidal thoughts of a year earlier had apparently been vanquished.

Unlike most Rikers inmates, Jordan has plenty of money. Since her first alleged request for legal representation, she has had the counsel of some of the finest defense lawyers in the nation. Ronald L. Kuby, the famed civil rights lawyer, and Alan M. Dershowitz, who served on the O.J. Simpson defense team, have both been part of her legal team (neither is now). So have many others who have since left the case. "Ms. Jordan has gone through 11 defense lawyers," noted The New York Times, "and has buried [Justice Charles H. Solomon of the State Supreme Court in Manhattan] and the appellate courts with motions to dismiss the charges or to grant her bail. The state court file now fills seven banker's boxes."

Her current defense team includes Norman Siegel, the former head of the New York Civil Liberties Union. Siegel does not question witnesses on the stand, and Jordan never seems to consult him. Most of her whisperings in court seem to be directed to Earl S. Ward, an avuncular lawyer who watches the proceedings with what looks from afar like wry resignation. He also almost never addresses the judge.

Most of the witness examination is conducted by Allan L. Brenner, who veers dramatically from injury to outrage, exasperated by everything but cowed by nothing. He is both craggy and lumpy. Even when smiling, he looks uncomfortable.

Jordan usually comes to court in a brown blouse and an ocher sweater that hangs to her knees, though she sometimes wears a long matronly gray thing. She looks like an aunt who had a good time in her 30s and has since settled down, though she will happily tell you about the good old days over a bottle of white wine. Her voice, when discussing the more mundane aspects of the case, was almost bouncy. Her facial expressions could be almost coquettish. For a woman who killed her only child, she is surprisingly likable, though a trio of female lawyers who sat behind me one afternoon compared her to Amy Dunne, the antagonist of Gone Girl.

Her testimony began with Brenner asking if, when Jude was already "in a comatose state," she climbed atop of him and forced more drugs down his throat, as the prosecution alleges.

"No, I did not," Jordan answered.

For the next two days, Brenner traveled through time and space with a dismaying lack of linearity, frustrating the judge and, from the looks of it, confusing the jury. This was not entirely Brenner's fault, for Jordan led a life of complexity compounded by wealth, illness and rancor. Some of this was probably necessarily, some of it surely inevitable. Some of it was just like any other life.

After working as a nurse in San Francisco, Jordan decided to return to New York in 1988. For a little while, she worked as a commercial real estate broker, then as a home health worker administering intravenous treatments. She thought the company she worked for wasn't very good at what it did. She thought she could be better. She was right. The home blood infusion company she started, Ambulatory Pharmaceutical Services, quickly became successful.

In 1990, a headhunter introduced her to Raymond A. Mirra, a Philadelphia businessman specializing in pharmaceuticals. He needed someone who was good at sales. Jordan was good at sales, but did not go to work for Mirra. He liked her anyway and began expressing an interest that was "more obviously personal," as she put it during her testimony. Mirra left his wife and moved in with Jordan in Manhattan in 1991.

The relationship turned bad almost as soon as it turned serious. Mirra, who had once been "profusely romantic" and an "aggressive lover," now developed a "strong interest in sado-masochism," which frightened Jordan. He was annoyed by the woman whom he'd sought. Jordan says he threatened her physically. Yet their business relationship flourished. The company in which they were now joint partners made, according to Jordan, several million dollars a year.

In 1998, two years after Mirra suffered a bout of thyroid cancer, Jordan and Mirra split personally, though not professionally. That same year, after the breakup, the two married, for what Mirra then said were "tax purposes," though Jordan says this was really a means for him to defraud her. Bank records from that year show that she was worth about $30 million.

Jordan was now in her late 30s and was "anxious to have a family." As she told the court, "Mr. Right" wasn't looming, so she decided that she did not need one. At a gym on Broadway, she met a Bulgarian yoga instructor named Emil Tzekov, dark skinned and dark haired, with a wide smile that seems not entirely trustworthy. He had reportedly overstayed his visa and was remaining in the United States illegally. In her 2011 bail application, Jordan submitted a photograph of Emil with his brother Mario, the two men wearing only shorts, showing off torsos lacking customary American flub. Between them, on their shoulders, hangs a blond girl of maybe 6 or 7. She wears a tie-dyed shirt and pink shorts. She is smiling. She is happy. The two brothers hold her by the ankles. The caption says: "VALENTINO BROTHERS IN ACTION :) :) COMING SOON ON DVD. :)."

Jordan explained what she wanted: a child, but not a husband. Tzekov consented. Jordan conceived. After a supposedly "normal pregnancy," Jude Michael Mirra was born on July 13, 2001. He had the last name of Jordan's former business partner because Tzekov was not equipped to take financial care of a child, while Mirra was. Why he agreed to care for a child that was not his, birthed by a woman whom he no longer loved, is not clear.

Then 9/11 happened, and it drew Jordan and Tzekov closer, as it did many other people around New York and across the nation. She decided she did not want to be in smoldering Manhattan with her infant. California beckoned once again. She and Jude flew out there. Tzekov was afraid that immigration authorities would nab him at airport security, so Mirra had one of his "go-fers," Bubba, drive Tzekov all the way across the United States. Jordan and Tzekov settled in a wealthy suburb in Marin County, north of San Francisco. Jordan divorced Mirra in November 2001 and married Tzekov less than a week later.

Jude developed into a "beautiful, happy, healthy, baby," Jordan said from the witness box, tears frequently interrupting her testimony. Photographs show a chubby infant with a mischievous grin, sort of like his father's. His eyes, though, taper at the corner like his mother's. By the time he was about a year and a half, he could walk and had in his vocabulary, by her estimation, 15 words. He was "very exploratory," so that Jordan had to get child safety locks for cabinets around the house.

But the locks proved unnecessary. As Jude's second birthday approached, he started to withdraw from the world. "He stopped talking," Jordan told the court, and started to "slip away." He wanted to play only with certain toys, to watch only certain videos.

Jordan recalled one especially exasperating afternoon. A cold rain was falling. Jude was at the screen door, banging. He wanted to go outside. Nothing could assuage him. Not knowing what else to do, she opened the door. Jude went out and sat on the deck, allowing the rain to soak him. This was around the time when a "feeling of desperation" took hold of Jordan.

In 2003, Jordan took Jude to the Koegel Autism Center at the University of California at Santa Barbara (UCSCB), where she estimated clinicians worked with him for five or six months. They most likely tried behavioral approaches, focusing on speech and social behaviors like pointing and making eye contact. These can significantly reduce the effect of autism in toddlers and even infants. Recent research by Dr. Sally J. Rogers, a colleague of van de Water's at the MIND Institute, found that a program called Infant Start could forfend autism in children 6 to 15 months old. The challenge is to catch the disorder in its earliest stages and to convince parents to stick with behavioral therapy instead of fleeing for exotic treatments promising instant cures.

Tragically, Jordan seems to have chosen the second of these options. She told the jury that the treatment at UCSB ended without "things improving." At this point, she decided to fight the diagnosis instead of the disease. She thought he had an autoimmune disorder with neurological symptoms (that could, of course, describe autism), a speech disorder called apraxia, a linguistic neurological disorder called Landau-Kleffner Syndrome that's closely associated with autism, eventually even pediatric catatonia. The National Institutes of Health lists more than 600 neurological disorders. A desperate and despairing parent could, ostensibly, have her pick.

The treatments Jude received were as scattered as the diagnoses for which his mother restlessly shopped: pulsed treatments of steroids, a blood-cleansing procedure called plasmapheresis, high-dose chemotherapy followed by stem-cell treatments, electroconvulsive therapy, not to mention dozens of psychoactive medications.

Jordan even thought that Jude might have an adrenal cancer called pheochromocytoma, for which he received a full-body MRI scan at Yale. No tumors were revealed, but Jordan persisted, and he was placed on a treatment of norepinephrine suppressors anyway. It did not help.

At the same time, the core symptoms continued to suggest autism: a lack of both receptive and expressive language, repetitive behavior, some lack of bowel control, erratic movements. Jordan must have known this, for many of the more than a dozen drugs Jude was taking at the time of his death can be used to tamp down autism symptoms. And they had been prescribed by a practice called Autism Associates of New York, on Long Island. Jordan's primary contact there, until his death in 2009, was a physician's assistant named Allan Goldblatt, who had an interest in the kind of neuroimmunological connection being investigated by van de Water and others.

In late 2007, Jordan seemed to crack, for, as her 2011 bail application notes, she was "no closer to finding out what was wrong with Jude. Their lives were dominated by his suffering, and his mother's search to find help." Jude wasn't getting better, she knew, but now a new thought occurred: It wasn't because he was ill. He wasn't ill at all.

It started with a bath, in December of that year, during which Jordan claims Jude told her that Tzekov—who, according to the 2011 bail application, had become "increasingly hostile, uninterested and unhelpful"—had effectively molested him. On the heels of that revelation came the morning when he rose from bed with shouts of "Dad bad."

Jordan began to believe Jude was trying to tell her that he had been abused by Tzekov and his family, as well as about 18 other people, including Mirra and a babysitter. He made these communications through simple utterances, and then through typing on a computer or a BlackBerry. "Jude described extreme, ritualistic forms of abuse, including oral penetration, anal penetration, forced ingestion of feces, and torture with needles by his father," according to the florid 2011 bail application co-written by Kuby.

Though she herself never contacted law enforcement about the alleged abuse, Jordan took Jude to therapists to treat him for his trauma (one of those therapists, Ellen P. Lacter, did file reports of suspected abuse, though it is unclear how seriously she took them). This became the dominant narrative of Jude's life, one that Jordan liked better than the incomprehensible tragedy of neurological affliction. Maybe you couldn't cure autism, but you could heal wrongs past. Or so Jordan thought.

Around the same time, she came to believe Mirra had forged her signature on documents, thus entitling him to much of her wealth. She thought he was having her followed by his associates from the Philly underworld. Eventually, she came to believe that he was scheming to have her killed, presumably because she'd discovered his deception.

It is true that some of Mirra's associates, particularly from his long-ago days as a tennis club manager, had credible ties to organized crime. But so did a number of men who ushered John F. Kennedy into the White House. Not even Jordan herself seemed to fully believe this story line, proffered so eagerly by Brenner in court. On the application to the Studio School in 2009, she listed Mirra as an emergency contact and a friend. (Mirra denies all these allegations through a lawyer, calling them in a statement provided to the press "false and irrational.")

By 2010, Jordan saw few options. Whatever progress Jude was making at the Studio School, she did not seem to notice. Her mind was filled with images of the abuse that had been done and the murder that would be committed. In February 2010, these twin terrors hounded her into a madness like the one that drove the ancient Greek Medea to a similar crime.

The prosecution was conducted on behalf of the people of the state of New York by Matthew F. Bogdanos, an assistant district attorney in Manhattan who is a colonel in the U.S. Marine Corps Reserves. Bogdanos served in Iraq and wrote a book called Thieves of Baghdad, about the theft of that nation's archaeological treasures. A Marine Corps mug is always visible on his table, just feet from the first row of jurors.

The courtroom was full for the start of Bogdanos's cross-examination of Gigi Jordan. Cyrus R. Vance, Jr., Manhattan's district attorney, was there. Eddie Hayes, the legendary trial lawyer immortalized as Tommy Killian by Tom Wolfe in The Bonfire of the Vanities, came up to the bench to chat, dressed in a customarily natty suit.

Bogdanos, a former middleweight boxer, did not land all of his punches forcefully, but the jury seemed much more captivated by his version of events than it had been by Brenner's. Then again, Bogdanos's tale was much simpler: Jordan was a liar and a murderer, one of the "careless people" who populate The Great Gatsby, only much worse.

While Brenner had tried to pander to the jurors' everyman sensibilities, Bogdanos referenced Edmund Burke in the first sentence of his opening statement, following that with a quote from Hamlet: "When sorrows come, they come not single spies / But in battalions." He did not harp on Jude's autism but made clear that he considered the diagnosis valid.

During his cross-examination, he broadcast to the jurors that the woman before them was worthy of nothing more than contempt. His angry, slightly high-pitched voice buckled in recounting the more preposterous aspects of her tale. And there were many. Jordan alleged that some 20 people had abused her son, yet she had never come close to witnessing such acts, even as they were presumably being committed in her home.

The defense had produced some statements Jude had allegedly written on a computer keyboard, with minimal assistance from Jordan:

"I wished to be a baby I couldn't be."

"After a while we just got used to being like this."

These had seemed implausible from the start, not only for any 6-year-old boy but one who had no evident recourse to spoken or written language. The most preposterous missive from Jude was introduced by Bogdanos toward the end of his cross-examination: "I want to aggressively punish God." Jordan maintained that her son had written it, even though the sentence is at a grade level of 7.3, according to the Flesch-Kinkaid scale. Patrick Henry's "Give me liberty or give me death" speech, by comparison, is at grade level 6.6.

Some had snickered while Brenner introduced the evidence of these e-seances, and even Judge Solomon seemingly struggled to keep a straight face. Bogdanos confirmed their suspicions by producing other things that Jude had written: long, incomprehensible strings of letters. These felt like the truer expression of his inner state. More damaging was the revelation that Jordan had coached her son on the abuse narrative, giving him notecards that said things like "Dad put his penis in your butt."

Jordan sometimes frustrated Bogdanos by citing her state of mind at the time, portraying herself as a woman hounded and confounded, and thus very confused. As of this writing, the trial is winding down, with closing arguments scheduled for the end of October. The jury may yet have pity on her, but Jordan will almost certainly spend a good deal of the rest of her life in jail.

Several days before Gigi Jordan took the stand for the first time, a play called The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Night-Time opened on Broadway. It is based on the 2003 novel by Mark Haddon, which was described in one review as featuring an "autistic 15-year-old-narrator" who "relaxes by groaning and doing math problems." He is also a skilled detective. Most reviews of the novel and the play mention both autism and mathematics. Most autistic children, though, do not have any special capacity for prime factorization. Nor are they, like the 1988 protagonist of Rain Man,

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.