Years before Fidel Castro, the defiant leader of revolutionary Cuba, died on November 25, his demise had been reported many times. The first was nearly 60 years ago, when the front pages of The New York Times and other newspapers flashed headlines about his death in a botched invasion of Cuba on December 2, 1956. The Cuban government, led by Fulgencio Batista, had spread the false story to stamp out a Castro-led insurrection, and for months the world believed that Fidel, and his younger brother Raúl, had met their inglorious end on a forlorn Cuban beach.

The truth of Fidel's unlikely survival wasn't known until the following February, when an American newspaperman braved Army roadblocks, often in disguise, to see the Cuban rebel in his mountain hideout in Cuba's Sierra Maestra. It was just after dawn, with a weak winter sun slipping over the mountains and the forest dripping from overnight rain, when the thick brush parted and into the clearing strode a young and very much alive Fidel Castro. It was February 1957, and the American reporter was mesmerized.

RELATED: Fidel's tumultuous relationship with the U.S.

"This... was quite a man—a powerful six-footer, olive-skinned, full faced, with a straggly beard," wrote Herbert L. Matthews in his exclusive front-page story in The New York Times. "The personality of the man is overpowering. It was easy to see that his men adored him and also to see why he has caught the imagination of the youth of Cuba all over the island. Here was an educated, dedicated, fanatic, a man of ideals, of courage, and of remarkable qualities of leadership."

That meeting between Matthews, a 57-year-old war correspondent and distinguished editorial writer, and the 30-year-old revolutionary with a law degree, marked the beginning of what would become a complex—and to some, troubling—relationship that helped propel Castro to power. It also raised early concerns about the truth of what appears in the news, or as it is more commonly known today, "fake news."

Over the next five years, Matthews' reporting created the myth of Castro, a genial Latin Robin Hood fighting for the poor and powerless. The writer's glowing profiles earned the Cuban leader the sympathy and support of the American public. They also helped solidify Castro's standing on the island and played into the revolution's dramatic about-face, which eventually led to the missile crisis in 1962 that nearly left the Western Hemisphere in cinders.

Notes Hidden in a Girdle

Castro's rise began on December 1, 1956, when the young lawyer, along with his younger brother Raúl, the Argentine doctor Ernesto "Che" Guevara and 79 young Cuban rebels tried to land their overloaded wooden yacht, the Granma , on the southeastern shore of Oriente province in Cuba. They planned to join supporters on land and launch a rebellion to depose Colonel Fulgencio Batista, who had ruled the country on and off since 1933, sometimes behind a puppet president. After being out of power for a few years, Batista ran for president again in 1952. Facing almost certain defeat, he launched a coup and scuttled the elections, including the congressional race in which Fidel Castro was a candidate.

Fidel then took up arms against the Batista regime, and on the morning of July 26, 1953, he stormed the heavily guarded Moncada military barracks in Santiago, on the eastern end of the island. The attack turned into a fiasco, as Batista's army rebels slaughtered or captured most of the would-be revolutionary rebels. Fidel and Raúl got away but were later rounded up by Batista's troops and sent to prison. Less than two years later, Batista, thinking the rebellion had died, released the brothers and others who took part in the attack.

But Fidel and Raúl weren't finished, and immediately resumed the fight. The brothers made their way to Mexico, where they enlisted support and raised money to buy arms and that second-hand yacht, Granma , vowing to return to Cuba, or die, by the end of 1956.

The rebels set sail from Mexico on November 25, 1956, (exactly 60 years before Fidel's death) but arrived in Cuba two days later than planned, missing the uprising that was supposed to have coincided with their landing. That wasn't all that went awry. Instead of anchoring off a shallow beach, the boat ran aground in a mangrove swamp, far from shore. The rebels waded through chest-high water, leaving most of their supplies behind.

Batista's forces were waiting for them. His planes strafed the rebels as they struggled toward land, killing many—but not all. That night, newspapers around the world carried a United Press International report that planes and ground troops had wiped out the rebels, including their leader, Fidel Castro.

Most of the rebels were killed or captured, but Fidel, Raúl, Guevara and a few others scrambled from the beach to the foothills of the Sierra Maestra, the crucible of Cuban revolutions. They set up camp, treated their wounds and began to recruit new supporters. For several weeks, Batista's government continued to report that Fidel was dead, and Castro remained uncharacteristically silent. Then he decided it was time to let the world know the truth.

He knew Cuban reporters feared Batista too much to tell his story, so he sent for a foreign correspondent. The New York Times reporter in Havana, R. Hart Phillips, had covered Cuba for decades, but few on the island knew R. Hart Phillips was a woman, one of the few female correspondents at that time.

Phillips was surprised to learn Fidel had survived, but she feared that writing such an incendiary story would get her expelled. Besides, Castro was considered a hothead and what she knew of the botched Moncada attack gave her little confidence that his rebellion would succeed. She turned down the interview, then offered it to her office mate, Ted Scott of NBC. Scott also said no—for the same reasons.

Phillips realized that the only way a journalist could do the story would be to fly in, interview Castro and then leave Cuba before the story ran. She called New York and passed along the information to Matthews, who was eager to conduct the interview.

Accompanied by his wife, Nancie, Matthews arrived shortly afterward. They waited in a Havana hotel for several days until they received a signal that the trip into the foothills was on. Their plan was to go into the mountains disguised as an American planter and his wife, scouting property.

The ruse worked. The Army waved the couple through barricades as they made their way to the Sierra. The rebels took Nancie to a safe house and brought Matthews to the edge of the Sierra, where he began a strenuous overnight climb. Cold, tired, hungry and ravaged by mosquitoes, Matthews reached the rebel encampment before dawn and waited there with his entourage until Castro emerged from the forest.

They talked for hours, sometimes in English but mostly in Spanish, with Matthews taking sparse notes on a few sheets of folded paper. He recorded a description of Fidel's rifle with telescopic sight, and he counted the rebel soldiers hovering nearby. Matthews shared some of the rebels' food, and he and Castro lit up cigars. Before leaving, the reporter asked the rebel leader to sign and date his notes to prove the interview had taken place, then rejoined Nancie. One of Fidel's men drove them back to Havana, where they boarded a plane to New York, Matthews' controversial notes hidden in his wife's girdle, where they knew she wouldn't be searched.

'Chapter in a Fantastic Novel'

Matthews wrote three articles about this dramatic encounter. The first ran on Sunday, February 24, 1957, as the New York Times announced on its front page that Fidel—believed dead since the previous December—was not only alive, but gathering strength. Most important, Matthews presented a version of Fidel that did not want power for himself. "Above all," he quoted Castro saying, "we are fighting for a democratic Cuba, and an end to the dictatorship." Castro vowed that his goal was to restore constitutional government to the island and hold elections. The Cuban revolutionary said he harbored no animosity toward the United States or the American people, and he mentioned nothing that even remotely resembled communist ideology.

When that first article appeared, Batista's government called it "a chapter in a fantastic novel." Despite the appearance on the front page of Castro's signature beneath a photo of him holding his telescopic rifle, Cuban officials noted that there was no photograph of Castro with the Times reporter.

The following day, the Times ran a blurry photograph of Matthews and Castro huddled together smoking cigars. The poor quality of the photo had kept it out of the paper until Havana challenged the integrity of the story.

Batista's censors kept most foreign newspapers out of the country, and they heavily edited those they allowed in. Even the copies of the New York Times delivered to the U.S. ambassador's office ran without Matthews' articles. But Castro supporters in the United States were clever. They pulled together mailing lists and sent photocopies to thousands of supporters, opinion makers and business leaders. Soon everyone in Cuba knew Fidel was alive and continuing his revolt.

For almost two years after that, Fidel fought Batista's army. But once the administration of President Eisenhower suspended arms sales to Batista in 1958, the end was clear. On New Year's Eve, 1958, while Matthews attended a party in Havana, and Fidel remained holed up in the Sierra, Batista fled Havana for the Dominican Republic with his family, a few close supporters and a pile of loot. The next day, rebels swooped into the capital and took control.

Castro came down from the mountains and made his way slowly across the island. On January 8, he triumphantly entered Havana, a day after the Eisenhower administration officially recognized the new government, which was comprised of moderate Cuban officials, and limited Castro to overseeing the armed forces. That arrangement didn't last long.

'I Am a Marxist-Leninist'

When Castro came to the United States a few months later, he was greeted like a celebrity. Although Eisenhower refused to meet him, he did talk with Vice President Richard Nixon, who said afterward that Castro "is either incredibly naïve about communism or under communist discipline—my guess is the former." In New York City, Castro spoke in front of the Overseas Press Club. For the first time, he boasted of fooling Matthews into believing his forces were far stronger than they actually were by marching the same men around in circles during the famous interview in the Sierra.

Matthews always denied that he had been tricked, but there is no doubt he was blindsided by Castro's secret embrace of Marxist ideology, as were many Cubans, including some who fought side-by-side with him. Rebel commander Huber Matos considered Castro's turn to communism as a betrayal, as did many others. Cubans across the island and in the United States blamed Matthews, and The New York Times, for complicity in the treasonous act.

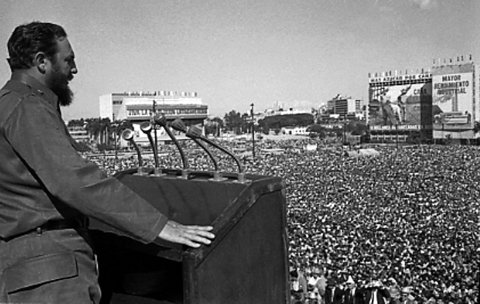

Matthews maintained extraordinary access to Castro, and continued to defend him and his revolution, insisting it was not communist "in any sense of the word," even as Cuba turned increasingly toward the Soviet Union. But after Castro proclaimed his revolution "socialist" just as the Bay of Pigs invasion got underway in April 1961, Matthews acknowledged the truth. Finally, during a fiery five-hour speech at the end of 1961, Castro defiantly declared "I am a Marxist-Leninist and I shall be to the last days of my life."

The power of manipulated news to shape world events was clear even then. Years after the revolution, Che Guevara wrote in his memoirs that Matthews' articles gave the rebels something more significant than a military victory. Many others saw it that way too. For years, anti-Castro Cubans picketed outside The New York Times ' headquarters, and mentioning Matthews' name in Miami's Little Havana still causes Cubans of a certain age to spit.

In the former Presidential Palace in Havana, now the Museum of the Revolution, an entire display case is devoted to the 1957 encounter between Matthews and Castro. On the seaside Malecon, Havana's most famous boulevard, a monument to Cuban heroes includes a brass plaque with Matthews' name.

And deep in the Sierra, on a hidden plateau that can only be reached by a several-hour trek across peasants' corn fields, through dense forests and across a muddy stream, stands a stone monument that memorializes the encounter between the American journalist and the rebel comandante— an encounter that created the myth that continues to inspire and haunt both countries to this day.

Anthony DePalma, a former foreign correspondent for The New York Times, is the author of The Man Who Invented Fidel.

Read more at Newsweek.com: