It looks like tapeworms have been upsetting guts for around 100 million years, as paleontologists believe they have discovered the first-ever proper fossil of one of the parasites.

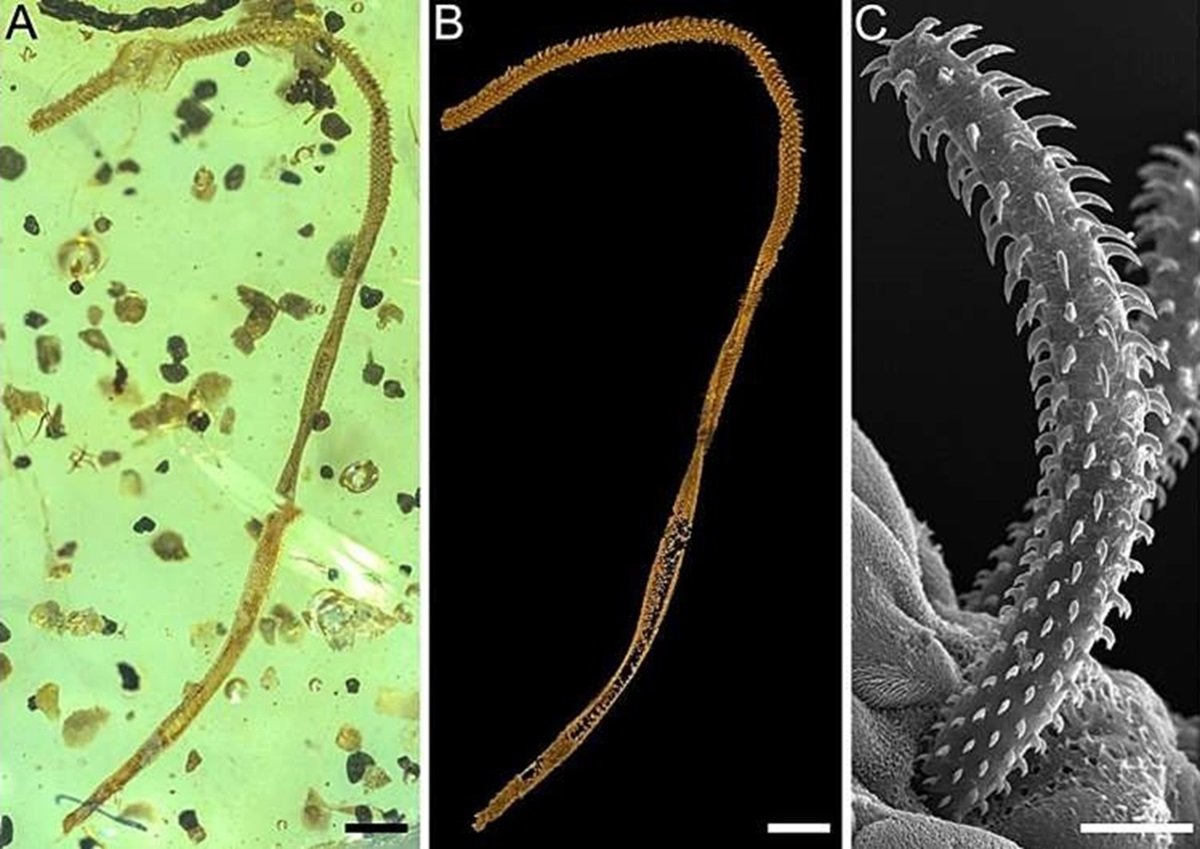

The partial worm—described by an international team of researchers led from China— was preserved in mid-Cretaceous Kachin amber from the Hukawng Valley of northern Myanmar that is believed to have formed on a prehistoric coastline.

It appears to be a tentacle, the features of which are consistent with the kinds of living tapeworms known to infect so-called elasmobranch fish like rays and sharks.

The researchers believe that the specimen had infected an elasmobranch host that got stranded on a beach by a falling tide or storm.

The poor creature was then bitten by a land-based predator or scavenger, during the process of which the tapeworm's tentacle was pulled free and got stuck in resin from a nearby plant.

Today, tapeworms are found in nearly all freshwater, marine and terrestrial ecosystems and infect all major groups of vertebrates, humans and our livestock included.

Tapeworms are so-called endoparasites, living inside their hosts. With neither mouth nor digestive tract, they absorb nutrients directly from the intestines of their victims, clinging on via a grasping head that usually has either hooks, suckers, or hooked tentacles.

Each typically infects two or three hosts across their lifespan, spread as eggs or larvae consumed via contaminated food, soil or water.

Adults, while growing long segmented bodies, can vary in size from less than 0.039 inches to a whopping 98 feet long.

While many infections result in no symptoms, in human hosts they can cause abdominal pain, diarrhea, tiredness and weight loss.

Although scientists have estimated that the Trypanorhyncha—the most diverse group of marine tapeworms—likely evolved around 200 million years ago, no fossils of the parasites have ever been found.

The study was undertaken by paleontologist Bo Wang of the Nanjing Institute of Geology and Palaeontology of the Chinese Academy of Sciences and his colleagues.

"The fossil record of tapeworms is extremely sparse due to their soft tissues and endoparasitic habitats, which greatly hampers our understanding of their early evolution," said Wang in a statement.

Despite how difficult it is for tapeworms to be preserved, the team has "reported the first body fossil of a tapeworm," Wang added.

Body fossils are those in which an actual organism has been preserved—as opposed to trace fossils, which record indirect evidence for life in the form of, for example, footprints, burrows, or feces.

Until now, the closest paleontologists have come to an actual tapeworm fossil came in the form of little circlets of hooks and sucking disks that were found on fossil fish from Latvia dating back to Devonian Period.

The Devonian—sometimes referred to as the "Age of Fishes"—spanned from 419.2-358.9 million years ago.

Although the arrangement of the hooks in these cases is consistent with living parasitic worms, no other bodily structures were found to support this interpretation.

A supposed body fossil of a disc worm was reported from Baltic amber dating back to the Eocene (55.8–33.9 million years ago), but this has since been reinterpreted as simply being air bubbles within the ancient resin.

Researchers have previously claimed to have found two cysts that resembled trematode flatworm larvae in other samples of mid-Cretaceous Kachin amber—however, no valid structural details were reported to support this assertion.

Presumed tapeworm eggs have also been reported from pieces of fossilized shark feces dating back to the Carboniferous (358.9–298.9 million years ago) and the Permian (298.9–251.9 million years ago).

While an embryo has been allegedly found inside one such egg, it has not been confirmed.

"This makes the current find the most convincing body fossil of a [flatworm] ever found," said paper author and paleontologist Cihang Luo, also of the Nanjing Institute.

Luo told Newsweek: "The morphology of this fossil tapeworm is close to the extant trypanorhynch tapeworms Dollfusiella and Nybelinia."

These modern parasites are known to infect houndsharks, nurse sharks, and rays.

Supporting the conclusions of previous studies into Kachin amber, other findings within the specimen indicate that it was formed in a near-shore environment.

The team found that the resin had encased both a scale insect nymph and parts of forked ferns, indicating a terrestrial setting.

Narrowing this down was the presence of sand grains distributed evenly throughout the hardened resin, hinting at a beach origin.

With their initial study completed, Luo says, the team "will keep looking for other bizarre fossils from Kachin amber."

The full findings of the study were published in the journal Geology.

Do you have a tip on a science story that Newsweek should be covering? Do you have a question about paleontology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Update 03/29/24, 1:41 p.m. ET: This article was updated with additional comments from Cihang Luo.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Ian Randall is Newsweek's Deputy Science Editor, based in Royston, U.K. His focus is reporting on science and health. He ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.