Researchers developing brain implants that could improve long-term memory have begun human trials, Nature reported.

According to evidence presented at the Society for Neuroscience meeting in Chicago in October, two studies funded by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, U.S. military's research wing, suggest that implanted electrodes could improve memory.

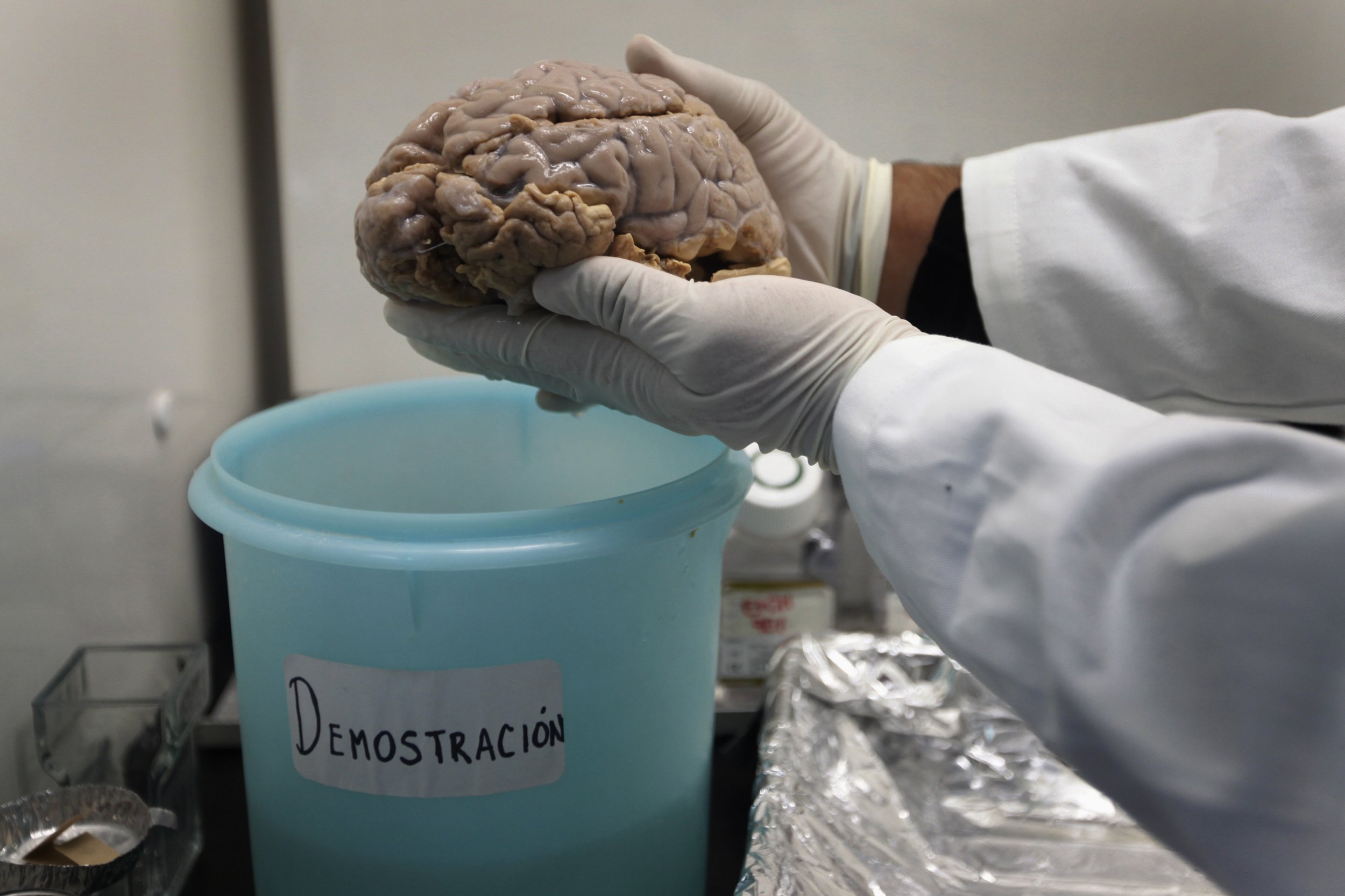

Memory formation is complex and not fully understood, but the hippocampus—a structure in the brain thought to also play a role in emotion—is believed to be central to the process. In short-term memory, the hippocampus is thought to collect sensory information and hold it in a readily accessible format. Recalling this information regularly helps solidify it into the long-term memory. The process by which long-term memories are formed involves an electrical signal traveling from one part of the hippocampus (CA3) to another (CA1).

In one of the recently presented projects, published in The Journal of Neural Engineering, a team of researchers from the University of Southern California (USC), Wake Forest University School of Medicine, and the University of Kentucky had 12 subjects with epilepsy look at pictures and then attempt to recall them 90 seconds later. As they did so, the researchers mapped the pattern of electrical signals fired between CA3 and CA1.

Then, they used this to develop an algorithm that could read the activity of the CA1 cells and spit out the predicted firing pattern of the CA3 cells. The algorithm was accurate 80 percent of the time. The idea, the researchers say, is that in the future, they should be able to stimulate a person's CA1 cells in a pattern that would mimic a correct CA3 signal. In other words, they could potentially help a patient whose CA3 cells were not firing properly improve their long-term memory.

USC biomedical engineer Dong Song told Nature that the method had already been tested on one female subject with epilepsy, who had electrodes implanted in her brain. Song said it was too soon to say if the subject's long-term memory had improved, but that the team planned to carry out further human trials in the coming months.

The second study, carried out by a team of neuroscientists at the University of Pennsylvania, recorded brain activity in 28 epileptic subjects while the subjects recalled a list of words. Using this information, the researchers produced an algorithm that could predict whether a person would forget a given word. When electrical stimulation to the brain was provided only when a patient read the words likely to be forgotten, memory performance improved by 140 percent.

Both of these research projects were originally aimed at helping soldiers suffering from brain injuries, common among those exposed to detonation of improvised explosive devices (IEDs) in the field. According to the Brain Trauma Foundation, up to 300,000 veterans of the Iraq war may be suffering from some level of traumatic brain injury, many instances of which are undiagnosed. However, the studies could also have implications for stroke victims and even those suffering memory loss through the normal aging process.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Conor is a staff writer for Newsweek covering Africa, with a focus on Nigeria, security and conflict.