On Thursday, Researchers announced the discovery of a new system to edit RNA using the revolutionary gene-editing technology CRISPR.

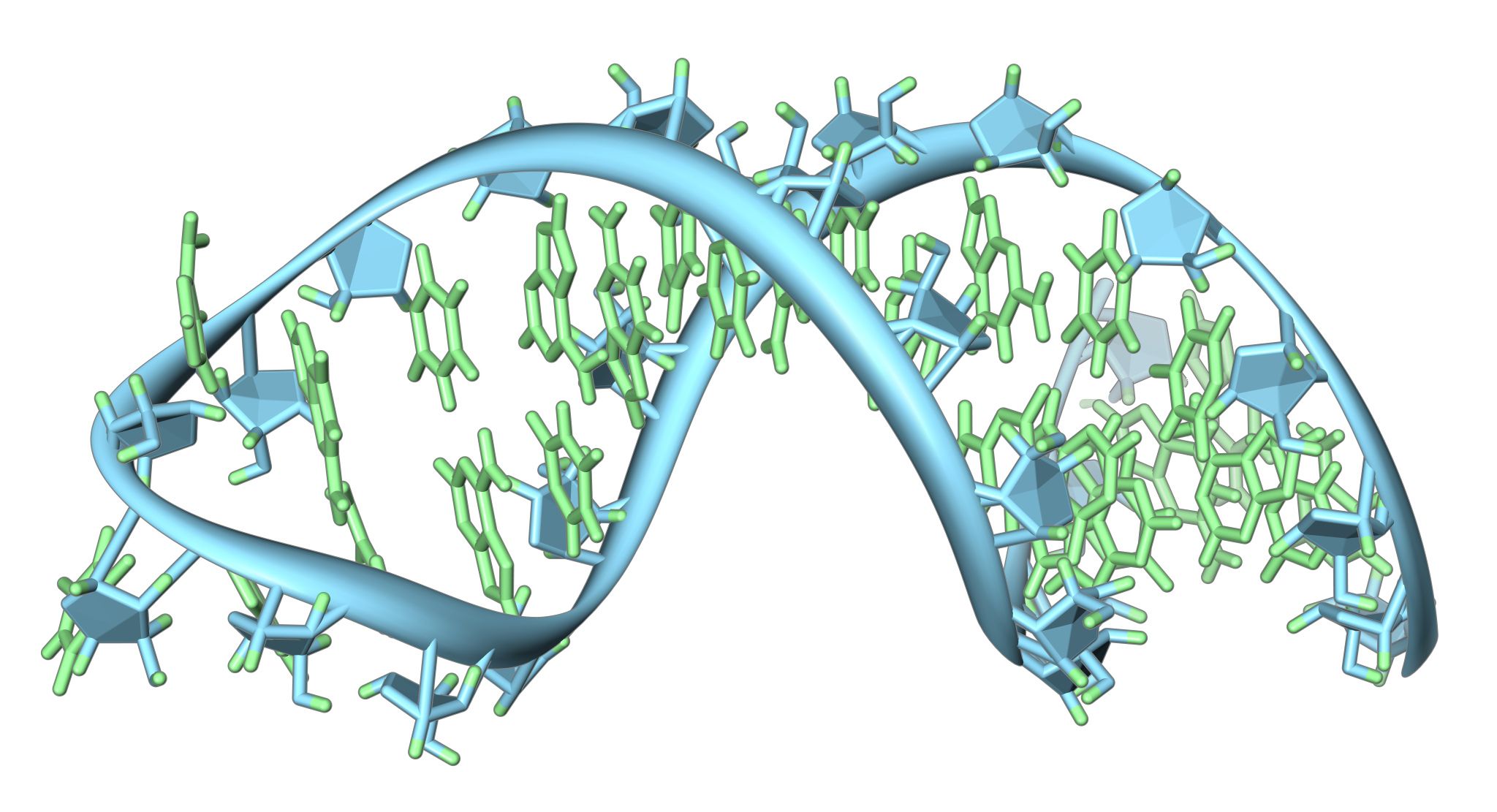

Whereas CRISPR Cas9, the full name of the system that has taken the bioengineering world by storm, is best adapted to edit DNA, a new paper published Thursday in the journal Science details a new system, called C2c2, to use CRISPR to edit RNA. The researchers, including Feng Zhang of the Broad Institute and Eugene V. Koonin, a senior investigator at the National Center for Biotechnology Information, say their research is highly preliminary, but the capacity to easily target and edit RNA could have a range of applications separate from DNA editing.

"There are some potential benefits in being able to target RNA with complete specificity. DNA is not touched," Koonin says. For example, the technology may open a new avenue to kill cancer cells. "In many types of cancer, the cancer cells will express a particular set of unique RNA molecules, such that are not found in normal cells." In principle, Koonin says, C2c2 could be used to "induce toxicity" into the RNA of these cancer cells. "Potentially you can kill cells that express a particular RNA molecule and not any other cells, by inducing that toxicity."

But Koonin cautions that so far his team has only used C2c2 in bacteria cells, like E. coli. The next step will be to try it in mammalian cells, and see if they get the same result.

"You have to realize at this time this is speculation. There are a variety of unknowns, and known obstacles between us and that end," he says. "This will not be something we figure out today or tomorrow."

In March, another team, which included Jennifer Doudna of the University of California Berkeley, manipulated the original CRISPR–Cas9 system to target and edit RNA, instead of DNA. Doudna and Zhang are in the midst of a deadlocked patent war over who owns the rights to CRISPR-Cas9; Zhang's team at Broad Institute was the first to use the technology on mammalian cells, while Doudna's was the first to publish a paper on it. The upshot of that legal battle, which will enter oral arguments in November, is likely to be a windfall—both in terms of professional fame and licensing fees—for whomever wins.

Koonin emphasizes that because C2c2 is a naturally occurring enzyme with "exclusive RNA capability," it might be more more efficient, and thus more useful for editing RNA than Cas9, which is a DNA-specific system. "[C2c2] is a very simple system. Of course, how efficient it is remains to be seen. We're very early in the game."

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Zoë is a senior writer at Newsweek. She covers science, the environment, and human health. She has written for a ... Read more

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.