Having already suffered from many varieties of institutional abuse and neglect, New York City's South Bronx has also fallen victim to cliché. For some, this spit of impoverished land is always the burning Bronx of 1977, a landscape best described with allusions to Hiroshima or Dresden. More recently, as the neighborhood's fortunes have improved, it has succumbed to shibboleths about "SoBro," a favorite topic of the New York Times real estate section. It even has breweries! And places to brunch! You're not still wasting your time on Brooklyn, are you?

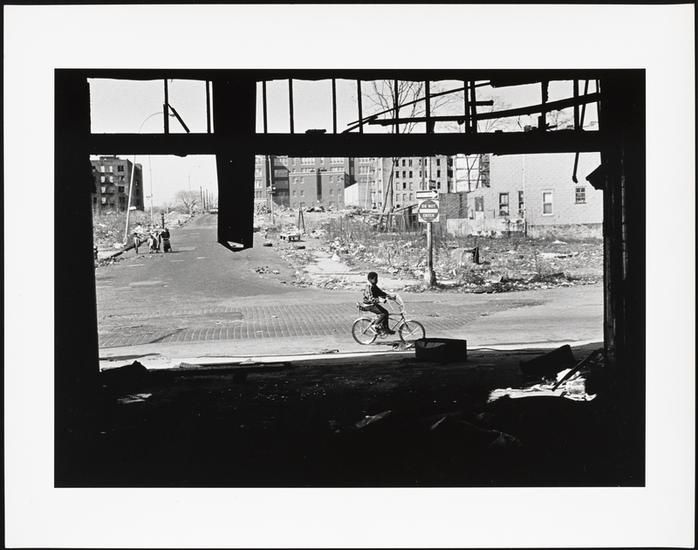

The avoidance of such facile imagery may be the best thing about the photographs of Mel Rosenthal, whose show "In the South Bronx of America" is now on display at the Museum of the City of New York until January 8 (the exhibition was supposed to close earlier this month but has been extended). Each of these 42 black-and-white photographs searches for something original and honest, something beyond the ruin porn that marks so much South Bronx photojournalism. Rosenthal captures the ruination of the Bronx without condemning the Bronx to ruin.

Today in his mid-70s, Rosenthal is a Bronx native born to a working-class Jewish family that lived on Sheridan Avenue, not far from Yankee Stadium. He went to nearby Taft High School, also the alma mater of director Stanley Kubrick. Like so many middle-class Jews before him, Rosenthal matriculated at City College, but that's pretty much where the conventional part of his life ended. After graduating from college and earning a literature doctorate at the University of Connecticut, Rosenthal traveled to Tanzania, where he worked as a photographer. Returning to the United States, he took a job teaching his chosen medium at Empire State College, which put him back in the Bronx.

The camera was his means of understanding what had happened to his native borough, his Virgil through the foreign landscape. But he also grasped that the taking of a photograph could not be a one-way exchange.

"The guys with the guns knew I was a nice guy," Rosenthal told The New York Times in 2011, explaining how he was able to carry on in a neighborhood where he had become an outsider. "I always gave pictures back to the people," he continued. "I always told my students, 'You lose points if you don't give pictures back to your subjects.'"

I have seen finer photographs of New York City in the chaotic '70s, but I have not seen photographs that so earnestly strive to capture the humanity of the people for whom that time was more than just a cultural curiosity. Without romanticizing poverty, Rosenthal teases out small moments of joy and grace.

A woman in a white dress executes a joyful dance move, as a single man somberly watches, sitting on the edge of what looks like a burned-out storefront; a shopkeeper stands proudly in front of El Cubano Deli, a man affectionately leaning on her shoulder; several boys pose on the stoop of an apartment building with "Harvard" chiseled above the doorway; several black teens sit on a slab of concrete, in the middle of a ruined building, where they are trying to create a community garden. They smile innocently, easily at the camera. In one especially poignant photograph, Rosenthal stands in his childhood room, which has been reduced to ruins.

"For Mel Rosenthal, there's no point in taking a picture if it isn't going to do some good in this world," photo editor James Estrin recently wrote in The New York Times upon the opening of the Museum of the City of New York's exhibition of his photographs. That mansioned institution sits on the northern edge of Museum Mile, which is also the southern edge of East Harlem, a neighborhood that, like the South Bronx, has emerged from the bad old days into strange new days of glass condominiums that function like airtight dormitories for the rich. But on the streets, there remain stories waiting to be told.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

About the writer

Alexander Nazaryan is a senior writer at Newsweek covering national affairs.

To read how Newsweek uses AI as a newsroom tool, Click here.