Outside of Comic-Con in San Diego in July, attendees discovered missing person fliers taped to surrounding poles and concrete walls. "Have you seen this child? Will Byers. Age: 12. Height: 4'8. Weight: 102 lbs.," they read. Below that was the hashtag "#StrangeHunt."

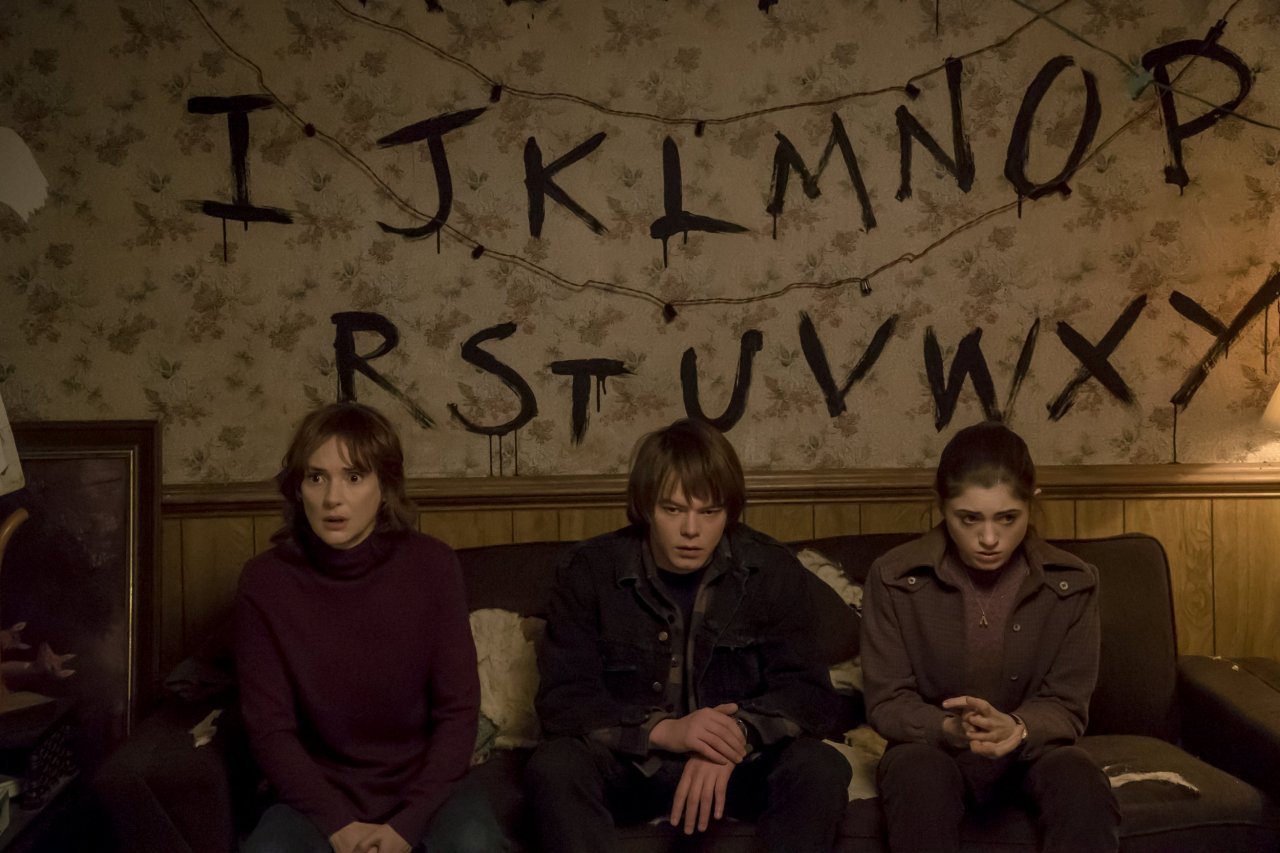

They turned out to be part of a (rather tasteless) marketing stunt for Stranger Things, the Netflix series that debuted July 15. Its plot is set in the 1980s and revolves around the disappearance of Byers, at the hands of a monster, and the attempts of his friends and family to find him, with the help of a girl with supernatural abilities. The show has received great reviews, with writers calling it "a cultural phenomenon" and "an instant cult classic." It's not hard to see why: The show is a thrilling tribute to '80s films, with the energy of Steven Spielberg in his prime. The show also draws on another element from that period, one that is far truer—and perhaps scarier—than the monster.

Byers goes missing during a time of national panic over the disappearances or abductions of children. "That was about the height of the missing child movement," says Robert Lowery Jr., vice president for the Missing Children Division of the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children.

Lowery notes that at the time, several missing child cases made headlines, including those involving Etan Patz, who disappeared in New York City in 1979, and Adam Walsh, who was abducted from a department store in Florida in 1981. (His father, John Walsh, went on to host America's Most Wanted.) A popular made-for-TV movie about the Walsh case premiered in October 1983.

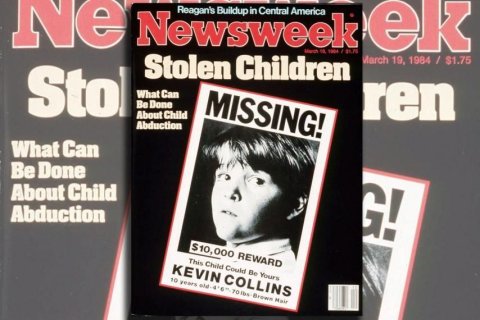

In 1984, Newsweek published a cover story on child abductions and the case of Kevin Collins, who disappeared in San Francisco that year. He was never found.

"Until recent years it was one of the secondary shocks for parents of stolen children that they were alone in their crisis—and often nightmarishly thwarted by foot-dragging police departments, jurisdictional tangles and an FBI unable to enter a case unless there was clear evidence of an abduction," the article said. That began to change with the Patz case, the article continued, and "since then, interest in the subject has snowballed."

"There was no infrastructure in place" for dealing with the issue at the time, Lowery says. Law enforcement agencies tended to conduct such investigations on their own, as the local county sheriff, Jim Hopper (played by David Harbour), does in Stranger Things.

This began to change, due largely to the work of parents of victims who became advocates. Congress enacted the Missing Children's Act in 1982 and the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children opened in 1984. Also that year, the faces of missing children began to appear on milk cartons nationally for the first time.

"So many tools we have today we didn't have then," Lowery says, referring to the early 1980s. The recovery rate is now 98 to 99 percent, according to Lowery, as opposed to the 62 to 64 percent in the period in which Stranger Things is set. "We're doing a much, much better job at responding to and finding and safely returning children than ever before."

Still, each year in the United States, nearly half a million children are reported missing, according to the FBI. Counting unreported cases, the figure could be more than 1.3 million. Almost half of the cases involve runaways or thrown-aways (children who are abandoned or kicked out of the home); an estimated 2 to 3 percent are stranger kidnappings.

"What happens in the late '70s and '80s is there's this huge anxiety that children are being taken in order to be exploited sexually and then sadistically murdered," says Paula Fass, professor emerita of history at the University of California, Berkeley, and author of Kidnapped: Child Abduction in America. Missing children saturated the news media and appeared on fliers and milk cartons.

"People were surrounded with what looked like demonstrations of the fact that children were disappearing," Fass continues. "Parents were taking out kidnap insurance. They were being advised by local police stations to have their children fingerprinted" so they could identify the bodies later.

Fass has not seen Stranger Things, but she says (minor spoiler alert) the paranormal monster that abducts Byers sounds like an embodiment of the "stranger danger" panic of the era, someone "having no face, coming from somewhere else." The show's main victim is also consistent with those from that time, she says—a prepubescent boy. And Fass says his mother, Joyce (played by Winona Ryder), fits an aspect of the panic at the time, which was that because of the rising divorce rate and women increasingly entering the workforce, parents were no longer around to look after their children 24/7.

Joyce's experience is consistent with those of the parents of missing children who have previously spoken with Newsweek. Those parents have said that they felt alone in dealing with the disappearance and that others were incapable of understanding what they were going through.

"It is a loss that is so different from other kinds of losses of children," Ruth Parker, whose sons CJ and Billy Vosseler were abducted by their father in 1986 and are still missing, told Newsweek in January. "You're frozen and you cannot grieve, you cannot finish the grieving process. Because if you do finish that process, you've given up."

Stranger Things is one in many on-screen portrayals of missing children. University of Cambridge professor Emma Wilson wrote in Cinema's Missing Children, her 2003 book,that filmmakers use the trope to explore "questions about the protection and innocence of childhood, about parenthood and the family, about the past (as childhood is constructed in retrospect as nostalgic space for safety) and about the future (as fears for children reflect anxiety about the inheritance left to future generations."

The missing child is especially suited for the horror genre. "I tend to see...the loss of the child as irreparable damage, as irrecoverable horror: horror which cannot be recovered in memory or representation, horror from which there is no absolute recovery," Wilson writes. On the screen, such stories show such a loss "as annihilating, immense and nonsensical."

For many viewers, the threat of child abduction or disappearance is scarier than any paranormal monster. Perhaps what makes Stranger Things so frightening and captivating is that it has both.

About the writer

Max Kutner is a senior writer at Newsweek, where he covers politics and general interest news. He specializes in stories ... Read more