In late April, a producer at Fox & Friends, the most-viewed morning news show in the U.S., approached Scientific American's public relations department and asked whether someone from the magazine would appear on the show and opine on the future of technology. For example, would teleporters be a thing in 50 years?

Michael Moyer, a senior editor at the magazine, agreed to appear. On the show, which aired April 30, he discussed topics such as the search for Earth-like planets. He didn't bring up climate change; later, however, he wrote that he had wanted to include global warming among his talking points, as it's "about the only interesting thing that the scientific community is sure will happen in the next 50 years." According to Moyer, Fox told him to "pick something else."

A spokeswoman for Fox later disputed that, telling Business Insider, "We worked closely with him and his team, and there was never an issue on the topic of climate change.… To say he was told specifically not to discuss it would be false."

Although there has long been a consensus in the international scientific community that climate change is real, this is not always what's portrayed on cable news networks. In a report published in April, the nonprofit group the Union of Concerned Scientists tried to assess the accuracy of climate change coverage on the Fox News Channel, CNN and MSNBC—the three most-viewed 24-hour-news channels. The organization found that Fox's 50 segments on climate science in 2013 were accurate 28 percent of the time, CNN's 43 segments were accurate 70 percent of the time, and MSNBC's 132 segments were accurate 92 percent of the time. (The 8 percent of MSNBC's climate coverage determined to be inaccurate skewed too strongly toward climate science, according to the Union of Concerned Scientists. "The handful of misleading statements were inaccurate in the same manner," the organization wrote in its April report. "All overstated the effects of climate change and specific types of extreme weather, such as tornadoes.")

While non-cable broadcast coverage of climate change has also come under scrutiny, cable news networks are often the subject of analysis because of their influence. Whereas broadcast networks do have news on them and are watched by many more people overall, cable news networks provide around-the-clock news coverage, which is why, according to a Pew Research Center's Journalism Project study, more people have said they "'regularly' get news from cable," compared with broadcast TV.

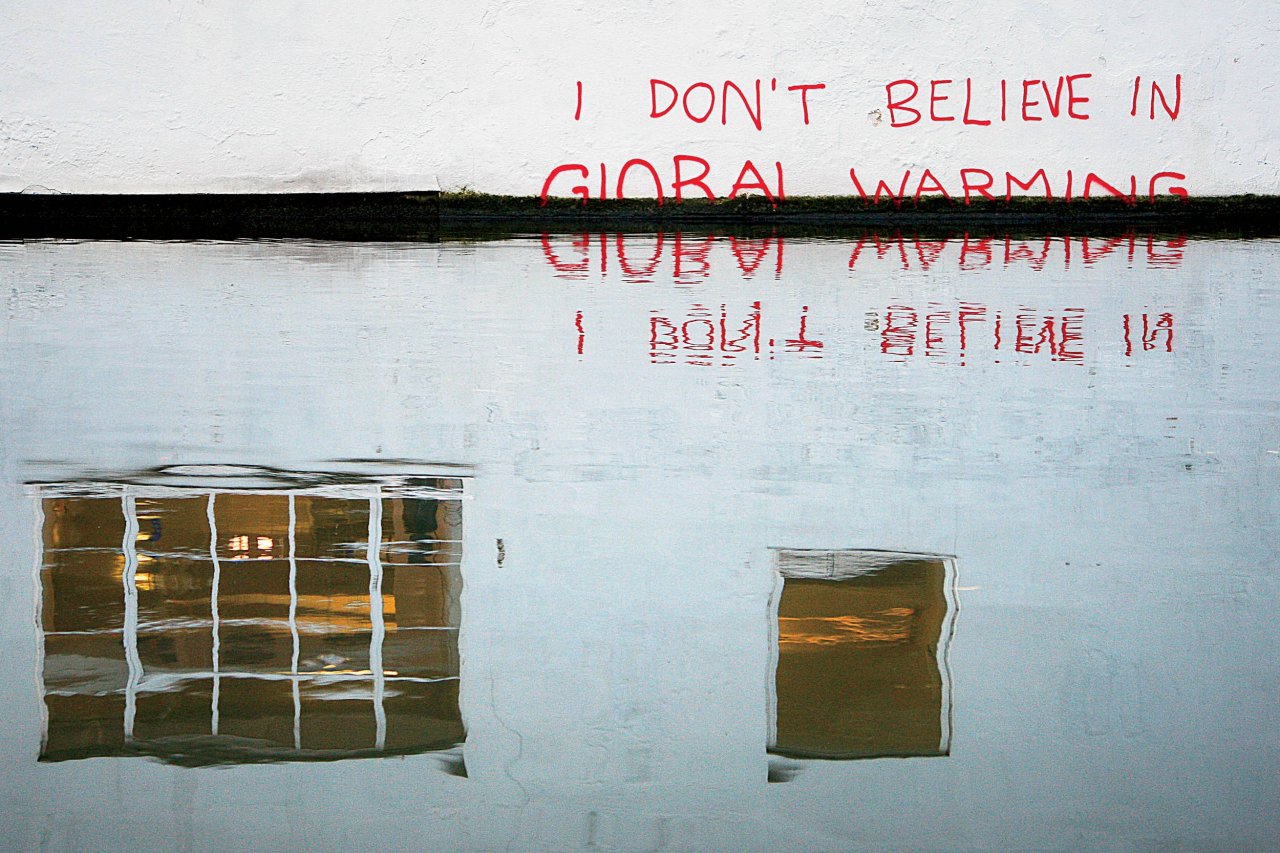

Misinformation about global warming is an old problem. When climate change first made the news in the early 1990s, the fossil fuel industry embarked on a public relations strategy similar to the one employed by Big Tobacco to combat anti-smoking initiatives decades earlier. Exxon and other fossil fuel concerns funded public relations firms and think tanks to release skeptical reports and press releases. According to research published in the 2010 book Merchants of Doubt, many of the scientists who worked to foster skepticism about tobacco risks also worked on these global warming denial campaigns, including Fred Singer, professor emeritus at the University of Virginia, and Frederick Seitz, a professor emeritus at Rockefeller University until his death in 2008.

They worked to "cultivate spokespeople and [entities] to attack the science, sow doubt and portray the science as something that was unsettled, uncertain and open for debate," Angelo S. Carusone, executive vice president of Media Matters for America, a self-described "progressive" journalism watchdog group, tells Newsweek.

The strategy worked. One 2012 study published in the journal Nature Climate Change found that despite near-universal agreement by experts that greenhouses gases lead to global warming, public concern about the issue has declined in recent years because of "the 'manufacture of doubt' by political and vested interests, which often challenge the existence of scientific consensus." The report also found a causal link between "perceived consensus" and acceptance of global warming. Essentially, acceptance tends to increase when the media highlight the fact of a scientific consensus. And on the flip side, if the media were to downplay the consensus, the public's acceptance of global warming would tend to wane.

So how do Fox and CNN decide how to cover a topic as divisive as climate change? A Fox News email leaked to Media Matters for America in 2010 revealed that in 2009 network VP Bill Sammon ordered staffers via email to "refrain from asserting that the planet has warmed (or cooled) in any given period without IMMEDIATELY pointing out that such theories are based upon data that critics have called into question. It is not our place as journalists to assert such notions as facts, especially as this debate intensifies."

Fox did not respond to emails seeking comment on its climate coverage.

Several former staffers at CNN tell Newsweek the network has no top-down edict to eschew accurate climate coverage. However, Peter Dykstra, who worked as the executive producer for CNN's science, weather and environment coverage (and who now publishes dailyclimate.org and www.ehn.org), says that much of the conversation is nevertheless tempered by the ultimate decision–maker: money. "Places like CNN are terrified of offending viewers and sending them to Fox," he says.

In the 2013 ratings of the top cable news channels, CNN tumbled to a 20-year low in prime-time ratings, at 568,000 viewers, just a smidgen more than half of Fox News Channel's 1.1 million. Meanwhile, news consumers are increasingly demanding narrowcast coverage—reporting that matches their biases. Fox appeals to the conservative segment of the market, MSNBC tends to attract a liberal audience, and CNN has tried to maintain a centrist viewership.

When the Obama administration released its National Climate Assessment on May 6, warning of increasing weather extremes because of global warming, all three news outlets covered it extensively: CNN featured 85 minutes of coverage, and Fox News Channel had 42, according to Media Matters for America. That would seem to be good news. But that coverage mostly was about spicing up a fiery debate, rather than considered analysis or discussion.

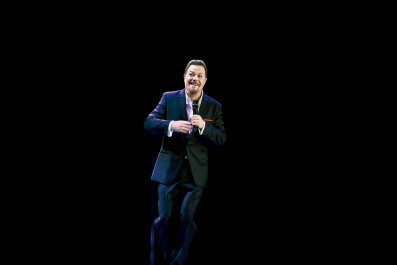

CNN, for example, aired a debate on the science of climate change between Bill Nye (The Science Guy) and Heritage Foundation economist Nicolas Loris. Nye is not and was never a climate scientist; he is a TV show host and comedian with a bachelor of science degree in mechanical engineering who has become an outspoken critic of climate change denial. The Heritage Foundation is a conservative think tank well known for its skepticism about climate change.

Nobody cared who won the debate, because the specifics of the argument didn't matter—the two men were debating an issue that has already been resolved. On the other hand, what did count was the fact that CNN let there be a debate at all. It drummed up media coverage, viewership and discussion, for all the wrong reasons.

Chez Pazienza, a former senior producer at CNN (he was fired for starting a blog without permission from his employer), says this type of skepticism-enabling debate about climate change is part of cable news culture: ramping up conflict where it doesn't really exist, for the theatrics. It's also a microcosm of cable news.

"There's this attitude that there is no real truth: 'There's two sides to every single story.' Even if 98 percent of scientists say, 'Climate change is absolutely real,' cable news will not present it that way," Pazienza says. "They'll say, 'Let's bring on a guy who denies climate change. That makes for good TV debate.'"

An earlier version of this article misidentified Michael Moyer, the editor at Scientific American.