I feel as if I am sitting in the front row of class on a day I haven't done the reading and the teacher just caught me checking Facebook. Stephen Kosslyn, founding dean of the Minerva Schools at KGI—a new liberal arts and sciences college that's seeking to upend everything we know about the undergraduate experience, and what we pay for it, too—just proposed a subject for debate: "It's always bad to have hidden agendas," he says. "Robin, can you give me a reason why it's always bad?"

Kosslyn rotates the computer toward Robin Goldberg, Minerva's chief experience officer, who oversees brand development, recruitment and student life. They're sitting in a conference room at their headquarters in San Francisco. I'm in Newsweek's office in New York City, and we're talking via Google hangout. Kosslyn, a former Harvard dean and cognitive neuroscientist, is demonstrating one of the many teaching techniques incorporated into Minerva's first-of-its-kind online teaching platform.

"Robin?" he says again.

Goldberg looks at me through the camera. "It's always bad to have a hidden agenda because you want to be transparent—

"Stop!" Kosslyn says. "Abigail, can you pick up exactly where Robin let off?"

I freeze. I'm not checking Facebook, but I have been furiously writing down what Kosslyn is saying when I hear my name. "It's always bad to have a hidden agenda because—" I begin, since repeating the question always buys you a little more time to come up with an answer. "Because you want to be transparent and build trust with your colleagues—

"Stop!" Kosslyn again. He gestures to Goldberg for her to continue.

"—so people will feel confident in your work," she concludes.

Kosslyn calls this kind of exercise "an intellectual baton race." You're not allowed to repeat what another student says (oops), which means you really have to pay attention.

"OK, now let's do con!" Kosslyn says. "Robin?"

"What?" she asks, looking up from her smartphone. "I was being a bad student," she says, proving Kosslyn's point. "I was multitasking!"

Minerva's curriculum features discussion-based seminars, all of them online and each with fewer than 20 students. Classes look a lot like souped-up Google Hangouts. At the heart of the school's pedagogy is an auspicious antidote to the barrage of distractions facing students in the 21st century classroom: its Active Learning Forum technology platform, which leverages a series of techniques—from quizzes and debates to break-out groups and relays (that complete-the-sentence exercise Kosslyn sprung on me)—engineered to enable professors to teach more effectively and encourage students to participate rather than zone out.

This fall, Minerva welcomed its founding class of 28 students from 14 countries (the school received 2,464 applications). Each received a full-tuition scholarship of $10,000 a year for all four years. Even without the scholarship, that's a significant savings, since the average college student with loans graduated with $33,000 of debt this year. By next fall, Minerva expects to have 200 to 300 students. Then, in five or six years, 7,000 undergrads, making it about the same size as Harvard. And Minerva's sticker price ($28,000, including room and board and fees) is a fraction of the cost of most other schools. At Harvard, annual tuition alone costs $43,938.

Minerva students spend their first year living together in San Francisco, their second year in Buenos Aires and Berlin, their third in Hong Kong and Mumbai, their fourth in London and New York. Sophomore year, they choose one of five majors (social sciences, computational sciences, natural sciences, arts and humanities or business) and a concentration, like global government or arts and commerce. "Minerva is not a place for a professor to come and say, 'I find Renaissance Gardens in Italy fascinating, I want to teach that,'" says founder and CEO Ben Nelson. "That's not a Minerva class. This is not a place to teach your hobby." Instead, the school prioritizes subjects that teach effective communication, creative thinking and critical thinking.

Nelson, who spent a decade as an executive at online photo company Snapfish, claims he's building the world's greatest university in history—from scratch. He calls Minerva "the meta-opportunity to make sure Ivy League graduates are once again thought of as the people we want to have lead society, not just the ones entitled to do so."

'A seminar on steroids'

"There is a good deal of evidence that students tend to tune out pretty early on in lectures," says James E. Ryan, dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Education. "They're not a very effective way of engaging students, nor an effective way of teaching students so they retain the material."

Minerva is decidedly anti-lecture and anti-introductory course. The school's central conceit, based on decades of research, is that active learning leads to better test scores, higher GPAs and meaningful retention. "We want everyone engaged at least 75 percent of the time, and we've designed a whole new way [to do that]," Kosslyn says. "It's a seminar on steroids. It allows you to teach in ways that you can't do in a traditional classroom, but more importantly, it allows students to learn."

"There are better ways to learn than rereading text. Obviously you have to read it in the first place, but to study it, there are many more things to do after that are better," says Henry L. Roediger III, a professor of psychology at Washington University in St. Louis and a co-author of Make It Stick: The Science of Successful Learning. "The trick will be making it more than just watching a talking head…. At Minerva you can."

In the first 10 minutes of a Minerva seminar, students take a quiz, "mostly to be sure they did their homework," Kosslyn says. "We need them to know their material because it's a vehicle for teaching." Students log their answers to the quiz online, and professors see the scores immediately. That way, they can address any questions and conceptual problems before moving on.

For the next hour, professors implement the teaching platform's many high-tech features. Kosslyn offers an example. Let's say a professor announces a debate over whether the U.S. government should eliminate funding for the National Endowment for the Arts. While two students present their assigned sides, the rest of the class isn't just sitting there listening. "If we left it like that, they'd be checking their email," Kosslyn says. "We have them doing something active." In this case, they might grade the presenters on a scale of 1 to 5, based on the strength of their arguments.

"We're in a constant group discussion, and our professors know us and call on us whenever we seem distracted," says Royi Noiman, a 23-year-old student from Tel Aviv. "It's long lectures that require getting used to. The seminars are more similar to how human interaction is!"

In Minerva's seminars, there is no front row and back row; no long tables where it's possible to hide. "It feels like you're always sitting next to the professor," says Jonathan Katzman, chief product officer. "It really brings a heightened awareness, a different level of consciousness as you're engaging in the classroom."

Minerva's platform also lets professors track how many times each student has spoken during class. "We know there are tons of biases that affect how professors call on students," says Kosslyn. "Women students don't get called on as much as male students." In each class, students' faces are displayed as thumbnails across the top of the screen. For them, it's always in alphabetical order, but "for faculty, we vary the order depending on who needs to be called on based on data we've collected before and how much they've been talking in class. It's a decision support tool that helps them overcome the traditional biases in class."

If students are answering a question, professors can send them silent notes to warn them that they're veering off course. Passing notes under the table, so to speak, works both ways; students can send professors messages if they don't feel comfortable asking a question out loud. "The benefits are far beyond just the academics," says Nelson. "A student struggling with psychological issues or going through a period of grief—you may figure it out after finals time. [At Minerva,] we can see, Is the student not in class? Or in class and not participating? Or have grades plummeted through in-class assessments?"

At the end of each class, students receive feedback from their professors about how they did and what they can work on. "I haven't seen any other examples of systems that do that," says Katzman. "The amount of feedback we give students on a daily basis is not even comparable to regular students" at traditional colleges and universities.

'The best. Thing. Ever.'

A few years ago, massive open online courses (MOOCs) started offering free Ivy League-level classes to anyone with a computer and an Internet connection. It didn't matter if you were a high school dropout in Toronto or a 70-year-old grandfather in Hong Kong; you could sign up and, poof, find yourself in "Financial Markets" with Bob Shiller from Yale or "A History of the World Since 1300" with Princeton's Jeremy Adelman. Along with you were hundreds, thousands, perhaps even tens of thousands of students watching the same video tutorials and participating in the same discussion forums.

The New York Times declared 2012 the "year of the MOOC." A year later, the word was added to the Oxford English Dictionary. Coursera, a for-profit company founded by Stanford University professors, and edX, the nonprofit MOOC purveyor founded by Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, have been praised for democratizing education. But they've also been criticized for their students' failure rates. And most people who take MOOCs aren't disadvantaged young people but rather white American men who graduated from college and have jobs.

Soon after famed scientist and former Stanford professor Sebastian Thrun founded Udacity, an online education company that offered MOOCs, he learned that less than 10 percent of its students finished their courses and only 5 in 100 actually learned the topic they were studying. (Udacity now focuses on vocational training and charges for classes.)

Minerva is, in a way, an antidote to MOOCs. "There's been a lot of changes in higher ed, but most have been incremental," says Ryan. "[Minerva] is one of the rare, genuinely new models—not only the online portion but the campuses around the world and the pedagogy as well. All that hasn't been put together into one package, and I think that makes it a really interesting and exciting proposition."

Noiman, who served his mandatory military duty in Israel before enrolling at Minerva, certainly thinks so. "I'm doing the best. Thing. Ever," he says. "All of my friends support me, most are jealous."

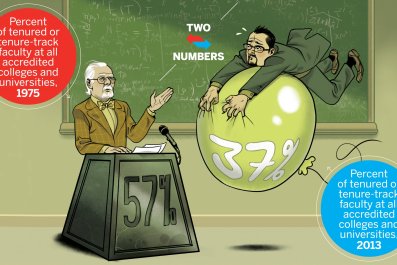

Yet breaking into the leafy ranks of the Ivy League requires a proven track record of success and a level of prestige, both of which can take decades, even generations, to solidify. And not everyone will want to spend college years taking classes online. But already, elite universities, medical schools, high schools and other graduate programs have approached Nelson about licensing Minerva's platform, he says. I ask which ones. "We've had universities approach us to take their entire tenured faculty and train them how to teach," he replies. "It's a very elite school, and I'll leave the name of the school anonymous to protect the guilty."

Perhaps the greatest proof that Minerva can become a viable option for college is the anecdote Ryan tells me at the end of our conversation. "I have an 18-year-old son," he says. "We went around to look at a bunch of colleges, and after a while they start to blend together. I'll describe a new school to him, and he half pays attention. I finally described Minerva, and he looked at me and stopped and said, 'Well, that's cool.' There is that 'huh!' factor to it. I've never seen a model like this."