Aross Europe, families have been eating the most traditional meals of the year – the great blow-out that for most of us is the key ritual of Christmas, the New Year, the Feast of the Epiphany and the winter solstice. A stroll down a European shopping street these days might tell a visitor that our food culture has become dull and homogenised, that we're a continent of burger and pizza eaters, cappuccino and cola drinkers, busy hunger-fixers like everyone else. But we still eat nine out of 10 meals at home and there, at celebration time, all the glorious differences of the European table still thrive.

We asked Newsweek readers across Europe what they serve up for the party season: it was quite a feast. The British ate turkey and plum pudding, while across Germany and eastern Europe there were spicy sausages and roasted carp; in most Italian homes there are usually seven or eight traditional dishes, from cappelletti – pasta parcels – in broth to roast salt cod. On tables in Denmark there were roast pork, and across all the Baltic states there were sweet and spicy pickled herring. Most Spanish families got through at least one leg of acorn-fed, air-dried mountain ham. Everywhere there is sugar and cake: panettone, plum pudding, stollen, gingersnaps, chocolates, and meringues. And so it has been, at midwinter in Europe, for thousands of years: we consume what we've worked so hard to get, and store up energy for the hard months ahead.

There's one other common denominator across Europe: the mid-winter feast was cheaper – if you wanted it to be – than any winter solstice celebration in history. There's choice that would be unthinkable to most of our great-grandparents – whether you're buying an organic goose at £16 a kilo or the £5 lobster that British supermarkets were trumpeting in December. Thrifty or lavish, we all are now guests at the discounted, buy-one-get-one-free year-round cheap food feast, eating more than we need and paying less for it – as a proportion of our incomes – than our grandparents did, or their parents before them. This, it turns out, is not entirely a good thing.

FALSE ECONOMIES

Outside our festive feasting, we're a continent that is broadly similar in food spending and tastes. Some national clichés turn out to be true – the Germans, with their 300 types of bread, spend more on flour and grains than anyone else, while the British spending on sugar outstrips any other European nation except Turkey. But it's not the French who eat the most cheese – that's the Greeks (31kg to the French 19.6kg). Nor is it the Swiss who drink all the milk: that falls to the Irish.

We are devoted consumers of the things that tax the planet highest. Generally, Europeans are cutting back on meat and fish, but these are still by far the most expensive item in our shopping baskets. Germans believe they eat a lot of meat but the French eat significantly more, while the Spanish eat a stunning amount of fish – twice as much as anyone else – and the Norwegians spend far more than any others in the continent on everything.

That's not because of greed, but the fact that Norway is a shockingly expensive place to eat or drink. Government figures state that dairy, bread and meat prices are 54-80% higher than in the rest of Europe. In our survey of Newsweek readers, we asked families to price the main dish at a recent family meal. Most cost between €2 and €4 per head – the Norwegians' were €7.50.

Norway can afford the welfare and other support that cushions these prices, and it is also one of Europe's leanest countries. Only 10% of Norwegians are obese, compared to 26% of people in Britain. And in that strange statistical gap lies an intriguing debate about the link between cheap food and poor health, the phenomenon of the "malnourished obese", and the rise of food banks at a time when food is historically cheap. That conversation leads, inexorably, to a difficult question: should we be paying more for our food for our own good?

Tim Lang, professor of food policy at London's City University puts it plainly: "Food in Britain and much of Europe is so cheap and so plentiful that people now over-consume and mal-consume: we have very little under-nutrition, but we have the catastrophic rise of non-communicable diseases that are largely diet-related. Diabetes, gallstones, cardiovascular disease, 30% of the cancers."

There's a host of other ills beyond poor health associated with cheap food: waste, environmental damage, poor health and the degradation of Europe's farm economy. Lang says: "For the whole of the modern age, politicians and businessmen have pursued the goal of cheap food as a good thing, a way to keep wages down. But the industrialisation to produce cheap food has directly led to the environmental calamity of climate change." A recent UN report stated that the greenhouse gases emitted by food production exceeded those of all of the world's transport system.

For environmental groups like Greenpeace and Friends of the Earth the toll exacted by the drive to produce ever-cheaper food has come to the forefront of their campaigning: "The supermarket-led race to the bottom on prices is bad for consumers and our environment as it forces farmers – here and overseas – into impossible choices: whether to farm fairly and sustainably and ethically . . . or make a profit. Existing problems with pollution, soil erosion, food scares and loss of vital natural services will get worse and ultimately affect prices and choice in the longer term," says Vicki Hird of Friends of the Earth.

THE BOTTOM LINE

Food in the rich world is now cheaper than at any time in human history. It is cheaper in Europe than anywhere else, apart from the United States.

Broadly, we in western Europe spend about half what we did, in terms of overall expenditure, on food compared with 30 years ago. The average is around 15% of all spending, compared with the 45% that's the norm in a country like Pakistan or Egypt. But within the statistics is a story of significant gaps in food prices and expenditure.

As you'd expect, food prices rise the richer a country is. But the amount spent on food as a proportion of all spending drops – a phenomenon known as Engel's Law, after the 19th-century economist. So in eastern Europe food prices are two-thirds of what they are in Germany; but while in Ukraine 37% of all expenditure is on food, in Germany the figure is about 11%. These differences tell us a lot about the negative impact of cheap food.

Few British shoppers will believe it, but food is startlingly cheap in the UK – even cheaper than for our near neighbours. The British spend 15% less than the western European average – our €1,611 each per year on food for home eating is about the same as the Greeks spend, despite the fact that the average Briton earns more than twice as much.

The average French person spends €2,237 on food every year, 38% more than the British. The British, in fact, at 11.4%, spend less of their total household expenditure on food than any other large country in the world, except the United States. Britain's poorest spend about the same (16%) as the western European average.

This will come as a big surprise to most Britons, who, if you ask them, see food as a major cost that has been getting much more expensive. It's true that British food prices have risen faster than inflation and more than in the rest of Europe in the years since the financial crisis of 2007. But Britons have reacted by buying cheaper food and less of it. Why? "Much of the explanation behind UK households' relatively low expenditure on food lies with supermarket price wars. For instance recent price wars over milk – four pints of milk now often retail for £1 – which have left milk often retailing below cost price," says Sarah Boumphrey, head of strategic, economic and consumer insight at market researchers Euromonitor.

British supermarkets habitually "loss lead" with products, fuelling price wars and using their power to force producers to lower their prices. Discounting wasn't invented in Britain: Aldi and Lidl, the chains now challenging traditional supermarkets all over Europe with a "pile it high, sell it cheap" strategy, began in Germany. But in several other European countries, selling at below cost price has been illegal, and other price supports for producers have survived. As we'll see, discounted food may have a role to play in poor health.

The most striking thing in the statistics is the difference in the price of meat. This also came up again and again in our anecdotal survey of readers. Mimi McGarry is a mother of three, a German married to a Briton, who lives in Berlin but whose job frequently takes her to London. "Meat is so much more expensive in Germany. Lamb, or roast chicken – we buy free range, and in Germany it is easily twice as much."

Price comparisons bear that out – especially with beef, where ordinary ground beef for mince or hamburgers can cost four times as much in western Europe (€5 a kilo for food-quality ground beef in UK, against €20 in a Spanish supermarket, our research showed). Cheap beef has of course been the subject of major scandals in Britain, and the suspicion remains in many consumers' minds that good quality meat just can't be provided that cheaply without damaging agriculture and consumers' health.

In November, 70% of British supermarket chicken was found to be contaminated with campylobacter, a type of bacteria spread by poor hygiene in processing. It is Britain's biggest cause of food poisoning – affecting 280,000 and killing 100 a year. There's no data on campylobacter contamination across the rest of Europe. But the 2013 scandal where donkey and horse meat from eastern Europe was found in beef burgers and other meals was largely a British and Irish affair – the two western European countries where the price of meat is lowest.

In one supermarket aisle only does Britain buck the notion that it enjoys the cheapest food of western Europe. That's vegetables, where we spend more than most of our neighbours. "This could be linked to British consumers penchant for out-of-season vegetables, and also the high proportion of vegetable imports – per capita imports of vegetables are much higher in the UK than in France for example, although not Germany)," says Sarah Boumphrey, head of consumer insight at Euromonitor. A key to the conundrum is the British taste for bagged fresh salad, even in the depths of winter. By weight, it is one of food retail's most expensive items. "Frankly, you can sell fresh vegetables and salad at any price you like to the British," a supermarket senior manager once told me.

Urban consumers have little idea about the relationship between seasons and price, or what to do with vegetables once they have them. Tesco, Britain's biggest supermarket chain, revealed in 2013 that 68% of bagged salads is thrown away, half of it by the store, half in the home. Professor Gad Frankel of Imperial College London, points out that though we buy them to make us feel more healthy, salads labelled "ready to eat" are a major cause of E. coli and salmonella poisoning.

Perhaps the most shaming side-effect of overly cheap food and the demands of modern retail is that now 30% of food bought in western European countries is thrown away in the home. £12.5bn a year of usable food is chucked in Britain, according to the government's waste agency – more than £700-worth per family.

In our survey, this, along with the wealth of choice, was what many people agreed would surprise their grandmothers most in the modern kitchen – "that I don't make sure every scrap and leftover is used".

It's thought that a similar volume of food is wasted during production, on the journey from the farm to the supermarket till. Statistics are thin, but campaigners estimate that half the food Europe imports or grows ends up in bio-digestion or landfill. That, and over-consumption, are blamed for the fact that Europe has to use twice the area of its landmass to grow its food – importing, for example, all the soy used in cheap animal feed from South America. "Cheap food destroys biodiversity and factory farming causes pollution: we're not living within our environmental means," says Professor Lang.

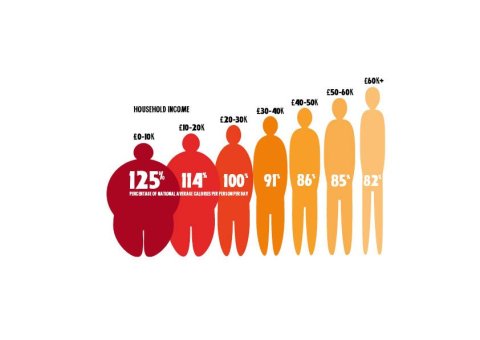

It's the relationship between cheap food and health that worries policy-makers most. Diet-related disease has become the primary cause of death in the rich world, and it will soon be the same in developing countries. Diabetes and obesity rates rise in western Europe pretty much in line with the graph that shows food prices dropping – reaching a nadir, as far as European obesity is concerned, in Britain, where food is cheapest of all.

THE COST OF THE CALORIE

Overall, eastern Europe is no fatter than western. And though food prices in countries like Poland and Romania remain much lower than they do in western Europe, rates of obesity and diabetes are not up to Britain's or most of western Europe's. The answer to this may lie in more traditional diets, including less processed food and more home cooking. In our survey we asked selected middle-class families to detail ordinary meals for the household: it was striking that the cheapest and healthiest came from the eastern European countries.

Matylda Rokosz of Zabkowice in Poland sent details and photos of a week's two-course evening meals that could have been a lesson to any concerned family cook. They were almost entirely cooked from scratch – cucumber and sour cream soup, cabbage and pork pierogi, barley and meat stew – each meal costing between €2 and €4.50 a person.

Matylda is clearly spending more time in the kitchen – two to three hours a day – than most cooks in western Europe would tolerate. (She thinks it's too long, too – "a duty, not a pleasure", she says.) But again there's a clear relationship between stove-hours and health.

Families that cook more are healthier, and Britain now has the lowest time spent cooking the evening meal of all countries in Europe – an average of just 32 minutes, down from 60 minutes 20 years ago. (We say "families", but our survey shows that it is still mainly mothers who do most of the cooking.) Cooking times drop largely because of convenience food; but ready-to-heat meals are generally heavier on sugar, salt and unhealthy fats than home cooking. There's a clear link between poverty and these foods: in Britain, those earning under £25,000 cook less than the rich. During the recession, these Britons spent 2% less time at the stove, compared with a 16% rise in cooking among Britons earning over £25,000.

Obesity is a good way of looking at the problem of food price, poverty, diet and health. Statistics are not confused by other causes, as they are with other diet-related illnesses like heart disease, where smoking is a major factor. But obesity is also an illness of poverty – in all rich societies the obesity/wealth "gradient" is very steep as you go through the incomes, and obesity is increasing fastest among the poorest in France, the UK and the US.

Nicole Darmon, director of research at the National Research Institute for Agronomy in Marseille, specialises in the economics of sustainable and affordable diets. She says it is more revealing to look at the cost of food not by euros per kilogram, but euros per kilocalorie. "It usually turns out that the foods that are healthiest for us, like fish, fruit or vegetables, are the most expensive. Food like biscuits or cake are a cheap source of calories when you have a low amount to spend." In France, buying 100kcal of energy will cost €1.39 if you eat tomatoes; but less than €0.20 if you eat crisps or sweet biscuits. Research in the States has linked rising childhood obesity in the 2000s to falls in the prices of the energy-dense and sweetened foods (while the price of vegetables and low-fat dairy increased).

This may go some way to explaining why twice as many adults in the UK are obese compared with those in France – and that the poorest French people are as obese as the average Briton. The latter spend a little more per head on sugar and confectionery than the French – €200 a year compared to €193.50, both well above European averages – but in Britain, sugary goods and meat are cheaper. According to the retail researchers Kantar Worldpanel, 37% of fat and 32% of sugar bought by the British is discounted or on special offer – far more than other goods. Since 2007, the only major food group the poorest Britons have bought more of is "sugar and preserves" – as a result, their daily energy intake has dropped less than that of all the other income groups. Are Britain's price-warring supermarkets pushing its people into obesity?

HEAVYWEIGHT SOLUTIONS

The notion that food is too cheap scares politicians. Rising food prices are electoral poison, as the bread price riots that sparked the Arab Spring of 2011 showed. "Food banks" and food aid schemes for the poor are one of the current shames of governments across Europe. But Tim Lang, who served on the British government's Sustainable Development Commission until the current administration abolished it, says that it is time for government to step in, to curtail the damage and the expense of overly-cheap food. The era of "leave food policy to the supermarkets" must end.

"The British ought to be spending more than we are – if we ate better diets and lived more healthily we could cut huge bills for health and environmental damage." In Lang's view it is the British middle class who should up their spending as a proportion up from the current 11% of overall household expenditure on food and drink to 15 or 20% (in a developing country like Pakistan, the proportion is 47%). "The rich need to pay more, and the poor about what they are paying now – but the latter need more income to buy healthier food."

Forcing prices up is not as unlikely as it sounds. Last December, a group of scientists led by Lord Stern, the British economist, called for taxes to push up the price of meat to reduce the burden that livestock imposes on the climate. Meanwhile, "fat taxes" are on the agenda in Europe. Using financial incentives as a way of steering people away from the cheapest and unhealthiest foods has, after much argument, now been deemed effective policy by the European Commission. France and Hungary have successfully introduced taxes on sugary drinks.

In the UK there have been calls from doctors for taxes on high-fat foods like chocolate biscuits. In 2013 the British Academy of Medical Colleges called for a 20% tax on sugary drinks, saying it would cut the numbers of obese people by 180,000. England's chief medical officer, Sally Davies, expressed support for the idea earlier this year. The food industry has reacted with its usual, and effective, threat that food price inflation will inevitably rise.

Nor do all in public health think raising prices is a solution – in fact it may increase problems for the poor. Nicole Darmon at the INRA in Marseille is one. "We've done experiments in controlled conditions, we asked them to buy with foods taxed according to health with low-income mothers and middle-income mothers. We found those who make the changes to diet are those who least need to. So it would be hard to increase prices for health reasons without increasing food inequality."

There's no likelihood of intervention on prices under the current English government. (In Scotland, which has the worst weight problem of all, with 27% of its adults obese and 65% overweight, the SNP administration is said to be looking favourably at sugar taxes.)

As ever, though, most European governments hope that their populations can, with prodding, be taught to buy and eat better.

AN ETHICAL INVESTMENT

Many middle-class Europeans are already raising the amount that they spend on food voluntarily. Our survey revealed that 80% of Newsweek readers are prepared to spend more on food for ethical reasons. (Buying local and sustainable food was the biggest priority, ahead of fair trade and organic.) Our interviewees in eastern European countries seemed even more concerned than those in the west about additives and pesticides – "I'm worried about the sugar content of the so-called 'healthy' products," said Judit Szabo in Budapest, ". . . and things I don't know much about, like genetically-modified products." Poles and Czechs also talked about the need to support local farmers.

Less than half our respondents thought food had got more expensive in the last year – although it plainly has across Europe, most of all in the UK (4.6%). This may be an indication of how insignificant food price changes now are to a middle-class that spends only £15 in £100 of its spending on feeding itself at home. In December 2014, Britain's annual statistical survey revealed that the richest 10% were spending three times as much on food as the poorest 10%.

While the politics of healthy, fair food supply seem stuck, public attitudes are on the move. We worry about food, perhaps more than we should. Most people tell pollsters they are concerned about food safety, provenance and their own food habits. Half our correspondents said they sought out food designed to make them healthy or lose weight. Many spoke of making an effort to cook from scratch more. Fifty percent of our readers said they were eating less sugar (10% said more!). At least half of them were making some further change like cutting down on alcohol, and – though only a handful were vegetarian – 42% were eating less meat.

Across Europe the complex environmental messages about cheap meat do appear to be making a mark. (According to a new report from the Chatham House think tank, emissions from livestock, largely from "burping cows and sheep and their manure", currently make up almost 15% of global greenhouse gas emissions. Beef and dairy alone make up 65% of all livestock emissions.) "There is clearly an awakening in consumers that cheap factory-farmed meat is bad for them, the planet and the animals – food scares, antibiotics, deforestation, greenhouse gas emissions and so on are all beginning to be understood as real reasons to eat less and better meat," says Friends of the Earth.

But it seems that moral reasoning on food is entwined with humbler concerns: the cheaper meat is, the less people are liable to put forward ethical reasons to cut down on it. The FoE's most recent survey, done as part of the Eating Better alliance, shows that in the UK 25% say they are eating less meat than a year ago, and only 2% say they are eating more. But in Germany, nearly 40% say they have cut their meat consumption. The number of people who think that "eating meat is bad for the environment" is up in countries like Germany, Sweden and France. There, 25-30% agree with the statement. Britain, where meat is uniquely cheap, lags behind – in fact, 44% of Brits disagree.

Of course there's ample evidence that we lie about our food habits. If all the people in Europe who claim to cut down on sugar had done so, one analyst says, half of Brazil would be out of work. In fact, sugar consumption is steadily rising across Europe. In one telling survey, people in Britain were asked if they managed to eat the recommended five portions of fruit and vegetables a day – 36% claimed they did. After some snooping, it turned out that only 11% were achieving the target.

Delusions they may be, but we spend copiously on our dietary fears: there's proof in the ever-accelerating European sales of what the food industry calls "FF+BFY" ("free from" and "better for you") processed foods and drinks, of which the British buy more than most. "Gluten-free" has been one of 2014's most successful in terms of growth: a December retailers' survey showed that 12.4% of Britons now buy gluten-free products. That's even though medical research states that only 1% of us are gluten-intolerant.

"There's money in health, and opportunities . . . " says a Kantar Worldpanel briefing for manufacturers. It goes on to point out "there are more people with diabetes in the UK than vegetarians". You can hear the corporate hands being gleefully rubbed: in fact what the industry calls "functional foods" – foods that claim to do things like make your skin better or your digestion smoother – have for 10 years been food retail's biggest growth area. Fifty six percent of Britons told Kantar that they are worried about being overweight (64% actually are).

But it says a lot about the business of buying good health that Britain's biggest healthy food shop is in one of London's richest areas, Kensington – which, with just 45.9% overweight, is the slimmest borough in England. A truly interesting social experiment in food, price and health would be to take Kensington's glitzy Whole Foods Market and open it in north-east England's Doncaster, where almost three-quarters of adults are overweight.

Despite the complexities, Professor Lang, a veteran of 40 years' debate on big-picture food policy, is hopeful: "We have to tackle a situation that is dire, but we are having a debate. The anger about food banks and the rise of food poverty is very encouraging. There's a really important movement building up around demanding decent food for people on low incomes and high-quality food for all.

"It won't be quick: we're in the middle of a long-term recalibration [of the food system]. I'm very optimistic, because without it, public health and the environment are in deep trouble."