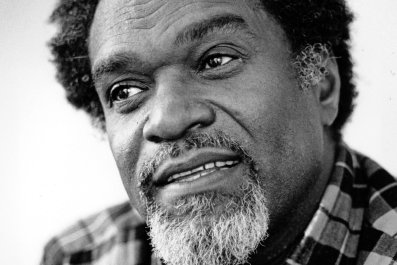

A year ago, three journalists working for Qatar's Al-Jazeera English network suddenly found themselves caught up in Egypt's harsh security crackdown following the military's overthrow of Islamist President Mohammed Morsi, the country's first democratically elected leader. Two of them, Australian Peter Greste, an award-winning former BBC correspondent, and Mohammed Fahmy, an Egyptian-born Canadian, were arrested when police burst into their office suite in Cairo's Marriott Hotel. The third, Egyptian freelance producer Baher Mohammed, was led away in handcuffs from his Cairo home after police shot his dog, Gatsby.

The journalists, locked away in Cairo's fortress-like Tora prison complex on the edge of the desert, were accused of helping a "terrorist organization" by broadcasting what Egyptian authorities said were erroneous reports reflecting Qatar's sympathies for the now-outlawed Muslim Brotherhood. After a lengthy trial, the three received seven-year jail terms. Mohammed, who had picked up an empty bullet casing from a demonstration as a souvenir, was given an additional three years for possessing ammunition.

On New Year's Day, an Egyptian appeals court agreed to a retrial, a decision that coincided with broader diplomatic moves toward a rapprochement between Cairo and Doha. But the retrial represents the only bright spot so far in an otherwise grim catalog of draconian security measures since Morsi's July 2013 ouster. Over the past 18 months, Egypt's repression has been more brutal than even the ugliest periods under former president Hosni Mubarak. Under the direction of Abdel-Fattah el-Sissi, the former general elected president in May, Egyptian security forces have opened fire indiscriminately on pro-democracy demonstrators, killing more than 1,400 people, human rights workers estimate. In swift trials, some lasting just eight minutes, more than 1,300 people have been sentenced to death or given life sentences on dubious terrorism-related charges. Thousands more, including local journalists, secular activists and supporters of the Muslim Brotherhood, have been jailed indefinitely for taking part in anti-government protests, which also have been banned.

Egypt's crackdown on political dissent has presented President Barack Obama with a difficult choice. On one hand, he is keenly aware of Egypt's strategic importance to the U.S.—from cooperation with anti-terrorist intelligence to maintaining the Israeli-Egyptian peace treaty, among other things. Which is why Obama has refused to characterize Morsi's overthrow as a coup, a step that would legally require the administration to halt all military aid to Egypt until the country restores democracy. But Obama also wants to be seen as a staunch defender of human rights and democracy, key demands of the Arab Spring protests that challenged autocratic rule in much of the Middle East. To that end, the conflicted president last year held up hundreds of millions of dollars of military aid to Egypt to signal his concern over human rights violations.

Now, however, Washington's strategic considerations appear to have trumped its human rights concerns. The reason: an incoming, Republican-controlled House and Senate concerned above all with the rise of ISIS militants across the region, as well as the huge influx of aid to Egypt from oil-rich Gulf states that has weakened U.S. leverage over Cairo. Last month, much to the dismay of democracy advocates, Obama signed legislation that allows him to invoke national security concerns to waive all the human rights conditions attached to Washington's $1.5 billion in mostly military aid to Egypt, such as requirements to hold free and fair elections and protect minority rights. And while Obama periodically speaks out against Egypt's dismal human rights record, there is little doubt among both administration officials and Middle East hands that he will use that waiver to keep the aid to Cairo flowing.

"We can harangue the Egyptians all we want about democracy," says Steven A. Cook, an expert on Egypt at the Council on Foreign Relations, told Newsweek. "But it doesn't get us anywhere."

The new approach toward Egypt represents a sharp turn away from last year, when Patrick J. Leahy of Vermont, the gravel-voiced Democratic chairman of the Senate panel that doles out foreign assistance, placed numerous conditions for Egypt aid—and conspicuously denied the president a national security waiver to maneuver around them. The ensuing delays in weapons deliveries infuriated the Egyptians, who felt Washington didn't fully comprehend the threats Egypt faces from Islamists at home and from rival powers in the region, such as Iran.

Egyptian officials point out that in addition to the threat posed by the Muslim Brotherhood, insurgents belonging to Ansar Beit al-Maqdis—a militant group that recently swore allegiance to ISIS—have killed hundreds of Egyptian security forces in the rugged Sinai Peninsula since Morsi's ouster. In these dangerous times, Egyptian officials argue, Washington should focus less on human rights and consider instead Cairo's long record as a reliable ally that has given U.S. warships preferential treatment in the Suez Canal, closely cooperated with U.S. intelligence against Al-Qaeda and joined other U.S. allies in the Middle East to blunt Iran's growing influence.

"The Egyptian attitude toward the Obama administration is, What is your problem? For 30 years you've been trying to drive a consensus in the Middle East. Well, here's the consensus: It's us, the Saudis, the Emiratis, the Kuwaitis and your friends, the Israelis, and you should listen to us," said Cook, paraphrasing the comments he's heard from Egyptian officials. "Why the hell are you bothering us about human rights and the Muslim Brotherhood? Why are you telling us to engage with the Islamists? We've got bigger things to do, like beating the crap out of them, dealing with ISIS and countering Iran."

That argument clearly prevailed on Capitol Hill, where a coalition of Republican defense hard-liners, bipartisan Israel supporters and parochially minded lawmakers whose districts stand to gain from Egypt's weapons purchases agreed it was time to listen to the Egyptians. Also, the Republicans' capture of the Senate in the November midterms stripped Leahy of his mantle as the Senate's top foreign aid appropriator and gave it to South Carolina Republican Lindsey Graham, an outspoken hawk who supports el-Sissi.

The administration appears to be happy with the turn of events. "We welcome the flexibility that the bill provides to further our strategic relationship with Egypt and our national security interests," said State Department spokeswoman Jen Psaki.

Human rights and pro-democracy advocates are frustrated about the change in policy, but they do see a glint of hope. While the State Department and the Pentagon are pleased Congress has removed the obstacles to resuming aid to Egypt, these advocates say Susan Rice, Obama's national security adviser, is still pushing human rights in Washington's dealings with Cairo. Just before Christmas, the White House said, Obama telephoned el-Sissi to voice his concern over the mass trials and the continued detention of journalists and peaceful activists.

And in what appears to be a move to exert some leverage over the Egyptians, some U.S. officials are now hinting that the administration might reconsider a decades-long preferential arrangement under which more than $1 billion in annual U.S. aid goes into an Egyptian bank account in one lump payment. The alternative—smaller aid payments spread out over the course of the year—would deny Egypt millions of dollars in interest.

Such attempts at gaining leverage over the Egyptians don't seem to be working. If anything, they have further stoked Egyptian doubts about Washington and driven Cairo closer to Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates and Kuwait. These wealthy Gulf nations share Egypt's suspicions of the Muslim Brotherhood as a subversive threat to their rule and have provided el-Sissi with some $32 billion in aid with no conditions attached. By contrast, Washington's annual $1.5 billion aid package now seems paltry.

Last year's delays in U.S. military aid prompted Cairo to use some of that money from the Gulf states to diversify its weapons suppliers and reduce its dependency on the U.S. Egypt and Russia have signed a $3 billion arms deal for two dozen advanced Mikoyan MiG-35 fighter jets, among other things. The deal follows earlier weapons agreements with Russia and France, signed last year, each worth more than a billion dollars.

Even with the likelihood that U.S. military aid to Egypt will now flow without conditions, the relationship still faces some rough spots. Egyptian officials are resisting American advice to spend its aid money on counterterrorism equipment and border security, preferring to buy more big-ticket items such as war planes and heavy armor that they believe will enhance Egypt's prestige and image in the region.

Yet these disagreements are unlikely to change Washington's decision to mute its human rights concerns. Which means the jailed Al-Jazeera journalists will have to count on a successful rapprochement between Egypt and Qatar for their release, rather than any further pressure from Washington. As an American working with the Egyptian military, who asked not to be identified, said, "I don't think the administration has much stomach to really push hard against Cairo."