As Wall Street investor Thomas Gilbert Sr. stood under the giant elm trees shading Princeton University's stately Nassau Hall on a sunny June Commencement Day in 2009, he saw a gleaming future for his son, Thomas Jr. "He's going to run a hedge fund!" the senior Gilbert, also a Princeton alumnus, declared with pride when asked what the handsome, 6-foot-3, blond-haired Tommy planned to do with his economics degree.

Things turned out very differently for both Tommy and his father.

Tommy, now 30, never held down a job after graduating and lived off his parents' handouts. And on January 4 he was arrested on suspicion of shooting his 70-year-old father in the head inside his parents' eighth-floor Manhattan apartment.

Tabloids and TV news were riveted by the drama of the wealthy scion who, according to an indictment, killed his father on a Sunday afternoon with a .40-caliber Glock pistol after asking his mother, Shelley, to run out and fetch him a sandwich. When she returned to her tony Beekman Place apartment shortly after 3:15 p.m., Tommy was gone and her husband was dead in the bedroom, the Glock not so artfully placed on his chest, as if to suggest this was a suicide. She called 911 and reported that she thought Tommy had murdered his father, court papers show.

When cops descended on Tommy's shabby, one-bedroom apartment in New York City's Chelsea neighborhood around 11 o'clock that night, after tracking him down by pinging his iPhone and ordering him to return to his apartment, they found ammunition for a .40 Glock, a Glock manual and carrying case, a speedloader, a red dot site for a handgun, 21 blank credit cards and a "skimmer" device used to steal credit card numbers. Arrested on the spot, Tommy was indicted by the Manhattan district attorney's office a few days later.

The details of the Tommy Gilbert case have captured the imagination of a certain portion of society in Manhattan and the Hamptons. After all, if money, good looks, an Ivy League education and an entrée to Wall Street aren't sufficient ingredients for happiness and success, what is?

"People are calling him a monster, but the person I knew wasn't a monster," a former Princeton classmate tells Newsweek. "He was a human and a likable one."

Marc Agnifilo, a lawyer for Tommy, declined to comment.

With his J. Crew looks (and a closet full of J. Crew clothes, according to a former girlfriend, Anna Rothschild), Tommy seemed like a classic New York WASP. He enjoyed the best education, starting with Manhattan's elite Buckley School and the Deerfield Academy boarding school in Massachusetts. The family belonged to the obsessively exclusive Maidstone Club in fashionable East Hampton, New York, close to where his father and mother own a house worth more than $10 million in the elite Georgica Association enclave. Nearly every weekend, even in winter, Tommy surfed the notoriously rough waves off Montauk, and he went to NASA space camp as a child, a former Princeton classmate said. "I remember him saying once after graduation, 'I always wanted to work there,'" the classmate said.

Shelley, a former debutante and the daughter of an AT&T executive, attended the all-female Ethel Walker boarding school, in Simsbury, Connecticut, and the all-female Hollins College in Virginia, two institutions known to draw proper, well-heeled young women. She worked briefly at a New York investment bank that later became known as Rothschild Inc. Shelley's society wedding in 1981 to Thomas Sr., at St. Bartholomew's church on Park Avenue, a Byzantine-Romanesque structure in which Vanderbilts worshipped, was followed three years later by Tommy's birth.

As blogs bristled with barbs about a "spoiled brat" and "trust-fund baby," NYPD Chief of Detectives Robert Boyce indicated at a press conference on January 5 that money was behind the ghastly crime. The senior Gilbert had been paying the $2,400-a-month rent on Tommy's Chelsea apartment, and New York's tabloids reported that Tommy was not happy with his father's threat to cut his weekly allowance to $300 from $400—hardly a princely sum in Manhattan.

Tommy is "clearly a bright, troubled kid" who had a "difficult relationship with both parents," says a person close to him who spoke on condition of anonymity. "He needs serious psychiatric long-term treatment."

While no evidence has emerged of a diagnosed mental health problem, there were some disturbing signs. Last September 18, court records show, Tommy was charged by police in Southampton with violating a June 2014 protection order taken out by Peter Smith Jr., whose father rode the Hampton Jitney bus on weekends from Manhattan with Tommy's father. Only three days earlier, in nearby Sagaponack, the Smith home, a 17th century historic mansion, burned to the ground in circumstances that are unclear. Lisa Costa, a detective with the Southampton police who is investigating the fire, says Gilbert is a "person of interest" in the blaze.

Tommy spent the five years since he left Princeton doing not much more than surfing, practicing Bikram yoga, working out, eating sushi and watching Netflix, according to Rothschild, who dated him in early 2014. Rothschild, a 49-year-old Manhattan socialite who runs a public-relations firm and is 19 years older than Tommy, encouraged him to attend black-tie gala events, where he would sip one glass of wine at most. Until he moved into the Chelsea apartment in May 2014, he lived in a dark, cramped basement studio apartment, also paid for by his father, near 86th Street and Lexington Avenue, where the Upper East Side starts to turn from pricey to gritty. "Tommy was quite well dressed and very clean, but that studio," with ragged furniture and a television with no cable service, "was appalling," says a person who saw it.

His signature trait, friends and former classmates told Newsweek, was his quietness. "Basically, he has no friends, his phone didn't ring and nobody texted him," says Rothschild. When Tommy told her he was interested in acting, she said she told him, "I don't think that's the best option for you, because you don't talk a lot." But last April she encouraged him to set up a session with a photographer to get professional modeling pictures.

Tommy apparently never talked, even to his former Princeton classmate, about why he had graduated two years later than expected, though court papers show he was busted for drugs on the eve of his original graduation date, in 2007. "He seemed kind of gentle but insecure," that former classmate says. "He always seemed ambivalent. He was sweet, but he seemed abnormally calm. He wasn't even anxious about his thesis." The 64-page thesis, titled "The Word Effect: Effects of the Word Content in the Financial Times on Firms' Earnings in the U.K.," is lightweight by Princeton standards. Wei Xiong, the economics professor who was Tommy's thesis adviser, says, "I honestly don't remember this student."

Despite his father's bold prediction at that commencement, Tommy was skeptical of Wall Street. He saw it as "having way too much power and control," the former classmate says. Others say that was a reflection of his attitude to his father, who was also a Harvard Business School graduate. "He would talk about how anything he attempted to do, it wasn't good enough" for his father, Rothschild says. "He probably figured, What's the point of having a job?"

Last May, Tommy did register a hedge fund, though it never raised any money, securities filings show. In an industry where fund names typically convey meaning, he called his the Mameluke Capital Fund. The Mamelukes were medieval slaves who rose up against their Egyptian rulers in 1250 and held on to power for nearly three centuries.

While wealthy in absolute terms, the Gilbert family was not superrich by New York standards. A will filed in Manhattan Surrogate Court shows Gilbert Sr.'s estate worth $1.627 million. Slayer laws would prevent Tommy from inheriting his one-third share if convicted. In a possible sign of a cash crunch, according to a former colleague of the father, the Gilberts listed their East Hampton home for sale last month for $11.5 million. (The listing was canceled after the murder.)

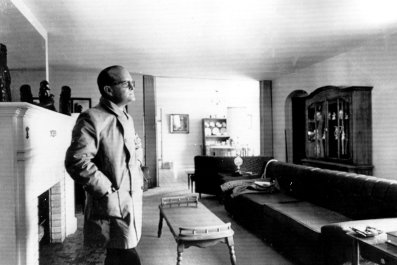

Thomas Gilbert Sr. "was driven by power, money and success," the former colleague tells Newsweek—particularly in recent years, as he struggled to grow a small hedge fund, Wainscott Capital Management, that he started in 2011 after four decades in private equity. The older Gilbert would typically sleep only four to five hours a night and fire off emails at 4 a.m. that were "frenetic," this person says.

Frenetic was the last word people would use to describe Tommy.

At the Main Beach Surf Shop in East Hampton, George "McSurfer" McKee remembers Tommy as someone who always took the path of least resistance, who was "a little below-average in turning and catching waves. He was kind of fooling around." While he always had plenty of surfboards, he tended to avoid the tough-to-control short boards, preferring a longer, wider "fishtail" board. "He would always," McKee says, "ride the easiest one to ride."