It has taken more than eight years. But finally, at 10am on Tuesday 27 January, the doors to court 73 at London's Royal Courts of Justice will swing open; the barristers, solicitors, reporters, and a host of other interested parties will troop in, and judge Sir Robert Owen will declare the start of a public inquiry into the death of Alexander Valterovich Litvinenko, a fugitive from Russia and newly-minted British citizen, who died in a London hospital on 23 November 2006.

At the centre of proceedings will be Marina Litvinenko, Alexander's wife for 12 years and a figure of preternatural calm and dignity amid all the hurly-burly and frustration of the near-decade since his death. In large measure, that these hearings are being held at all, and that they have been designated a 'public inquiry' rather than an inquest, represents a personal victory for Litvinenko, reflecting her dogged determination to find out how and why her husband died.

She also wants to know whether the UK security services could have done something to save her husband. The British government, in its standard phrase, "neither confirms nor denies" her assertion that Alexander received a regular stipend from the British intelligence agencies.

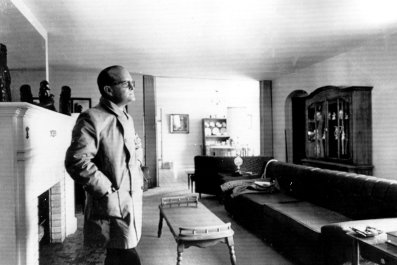

At the time of his death, he had lived in Britain – with his wife and young son, Anatoly – for six years. A fugitive from Russia, he had spoken out ever more boldly against President Vladimir Putin and rights abuses in his homeland.

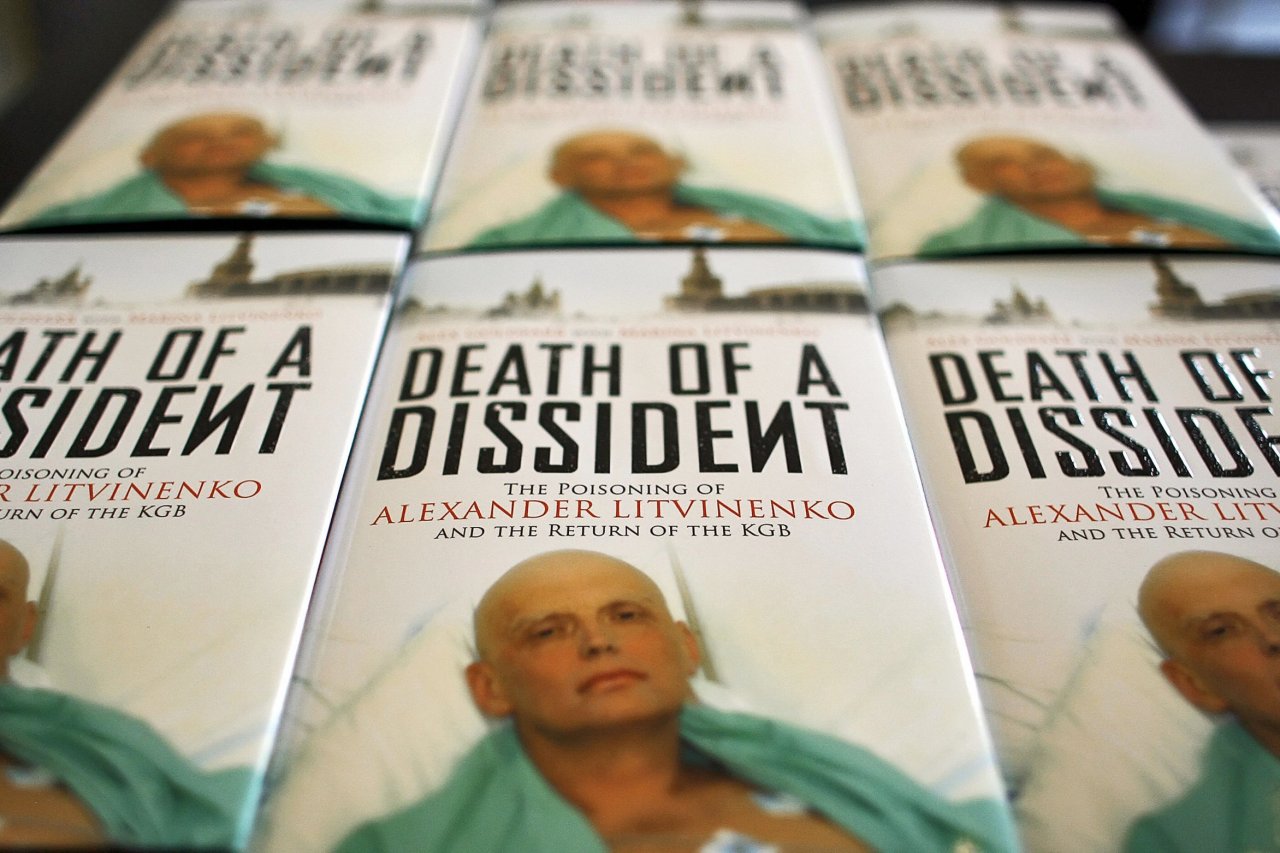

What else he may have done with his life, however, was largely eclipsed by the way in which he died: poisoned, as it was established too late, by the radioactive isotope, polonium-210. To readers of the British press, Litvinenko will forever be a bald and emaciated figure in a green gown in a hospital bed, whose last testament was to accuse Putin of his murder. At the time, all the elements combined to tell a simple story, and an official narrative soon settled down. According to it, Litvinenko had been killed on the orders of the Kremlin because of his increasingly vocal opposition.

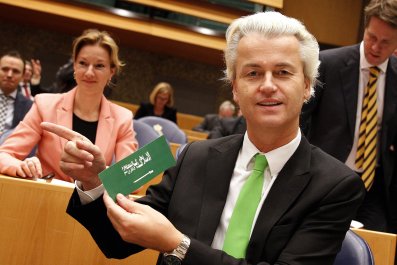

Russia was one of very few countries to produce polonium-210. Scotland Yard's investigation led investigators to a certain KGB officer-turned-security consultant, Andrei Lugovoi, who was charged in absentia. Efforts were made to secure his extradition, but they failed, with Russia invoking a constitutional ban on extraditing nationals. A diplomatic stand-off between the UK and Russia ensued, with tit-for-tat expulsions initiated by a furious David Miliband, who at the time had just become foreign secretary.

But this was not just a dry tale of diplomatic shenanigans. The Litvinenko affair came adorned with all the seductive baubles of a spy thriller. There was Litvinenko's own shadowy background in Soviet and then Russian intelligence. There were the polonium tracks across London and in British Airways planes in distant parts of the world. Don't panic, Londoners were told, even as the spectre was conjured up of a criminal, armed with deadly radiation, loose in the UK capital.

Litvinenko's movements shortly before he became ill included lunch with an Italian agent and investigator, Mario Scaramella, in a Piccadilly sushi bar, and a meeting with Lugovoi – who, it turned out, was a long-time associate – at the Pine Bar in Mayfair's Millennium Hotel. It was here, police concluded, that the deed had been done, when a deadly dose of polonium was added to Litvinenko's tea. Boris Berezovsky, the émigré oligarch, fierce Putin foe and incorrigible schemer, had more than a bit part. Litvinenko, it emerged, had been partly in his employ, and Berezovsky had funded the family in London. Reinforcing the cloak-and-dagger atmosphere was the coincidence of the new James Bond film, Skyfall, hitting the screens, with spectacular sequences shot around the Thames-side headquarters of MI6.

Months trundled by; then years. The law requires that mysterious deaths be investigated, and they hardly come more mysterious than Litvinenko's – or more potentially threatening to public safety or to diplomatic relations. The first step is to conduct a post-mortem, which was duly done in the hospital basement, by three doctors encased in protective clothing. The second is to open an inquest and the third, where a crime is suspected, is to put the presumed perpetrator on trial. In fact, a trial commonly supersedes an inquest, as the same evidence is likely to be heard. In the Litvinenko case, Russia's refusal to deliver up Lugovoi delayed, and eventually thwarted, the possibility of a trial.

There was further delay to the inquest when the coroner, who should have conducted it, first fell ill and was then replaced for (unrelated) misconduct. It was postponed once more by government attempts to protect most intelligence evidence. And lastly, it was delayed by judicial wrangling about its status: whether a case with so many ramifications should not take the form of an inquiry. The home secretary opposed this. But after a court challenge and – something ministers deny was related – the implication of Russia in the downing of the Malaysian airliner in eastern Ukraine last year, the government changed its mind. The inquest was redesignated a public inquiry.

In practice, the distinction will be modest. The inquiry allows the judge – but no one else – to consider secret intelligence evidence; that would not have been so with an inquest. But how much will remain secret is still in doubt.

The years of delay nourished a clutch of conspiracy theories, but the official version of events and motives has been set for so long that few expect Owen to turn up any surprises, despite his repeated resolutions to undertake a "fair and fearless" inquiry. UK public opinion has largely tired of the story, dismissing it as just another example of Kremlin thuggery.

Yet the gaps and inconsistencies that have been pointed out by some of those lumped with conspiracy theorists are fundamental to documenting, if not actually explaining, what happened. The most glaring, seen as the key to any inquiry by the US investigative author, Edward Jay Epstein, among others, is the publication of the post-mortem findings. Although Litvinenko's death provoked shocked headlines and prompted a drawn-out diplomatic row, the actual post-mortem results have never been released, not even to support the UK's extradition request for Lugovoi.

As the British investigative reporter David Habakkuk notes, it is still not at all clear who contaminated whom, and in what order. There remain questions about the role of Berezovsky in "managing" information, and the role of a certain businessman, Yuri Shvets (who was the focus of a BBC radio investigation soon after Litvinenko's death).

A Soviet-era exiled scientist, Zhores Medvedev, insists that Russia itself is among those who argue that the country is not the only source of polonium. There is evidence, too, that in the wake of Berezovsky's death last year, Scotland Yard is taking a new look at its earlier investigation into the Litvinenko case. Some also maintain that Owen has retreated from his earlier assumption that this was a (Russian) state-directed assassination. This line was put about, first by anonymous security sources, and later by the director of public prosecutions at the time, Ken Macdonald. If true, this would change a great deal.

There is plenty, in other words, for Sir Robert Owen to get his teeth into, if he so chooses. Marina Litvinenko, meanwhile, remains stalwart in her faith in British justice. In interviews, she has said that there is no such thing in Britain as Russian-style "telephone justice", and the that law had to be allowed to take its course. Her solicitor, Elena Tsirlina, insists that her client is "happy" with the inquiry arrangements, including the anonymity granted to many witnesses and the amount of evidence likely to be heard in secret. "She has full confidence in Sir Robert Owen," she told me.

In Ben Emmerson, Marina Litvinenko has one of the country's most revered barristers when it comes to challenging the establishment. But there are many – including Epstein, in a recent book about unsolved cases – who doubt that the truth will ever come out. He observes that the least likely to be resolved are those where there is state, and especially multiple-state, involvement. Less conspiratorially, there is the abiding truth that justice delayed is justice denied. A lot of truth can go missing in eight years.