On a raw, wet night in early December, Ravi Coltrane walked into the warm glow of center stage before a packed house at San Francisco's SFJAZZ Center. He opened a notebook on his music stand and began to recite a poem. Through his tenor saxophone.

From the bell of the horn came a clear cadence of syllables, rising and falling intonation, speech-like appeals. Piano, bass and drums churned up undulating waves of sonic support. Fellow saxist Joe Lovano echoed Coltrane's phrases through his own tenor. The conversation grew urgent: call and response, faith and struggle, the black church and the blues. No one in the audience had heard the words Coltrane had been glancing at, but they got the message. The standing ovation lasted several minutes.

"You know, it's kind of a heavy thing to do," he said of the performance. Except when speaking through a saxophone, he's a quiet guy, partial to understatement. It's one way in which Ravi Coltrane is like his father, a man he never really knew but whose name and achievements have shaped and challenged his world.

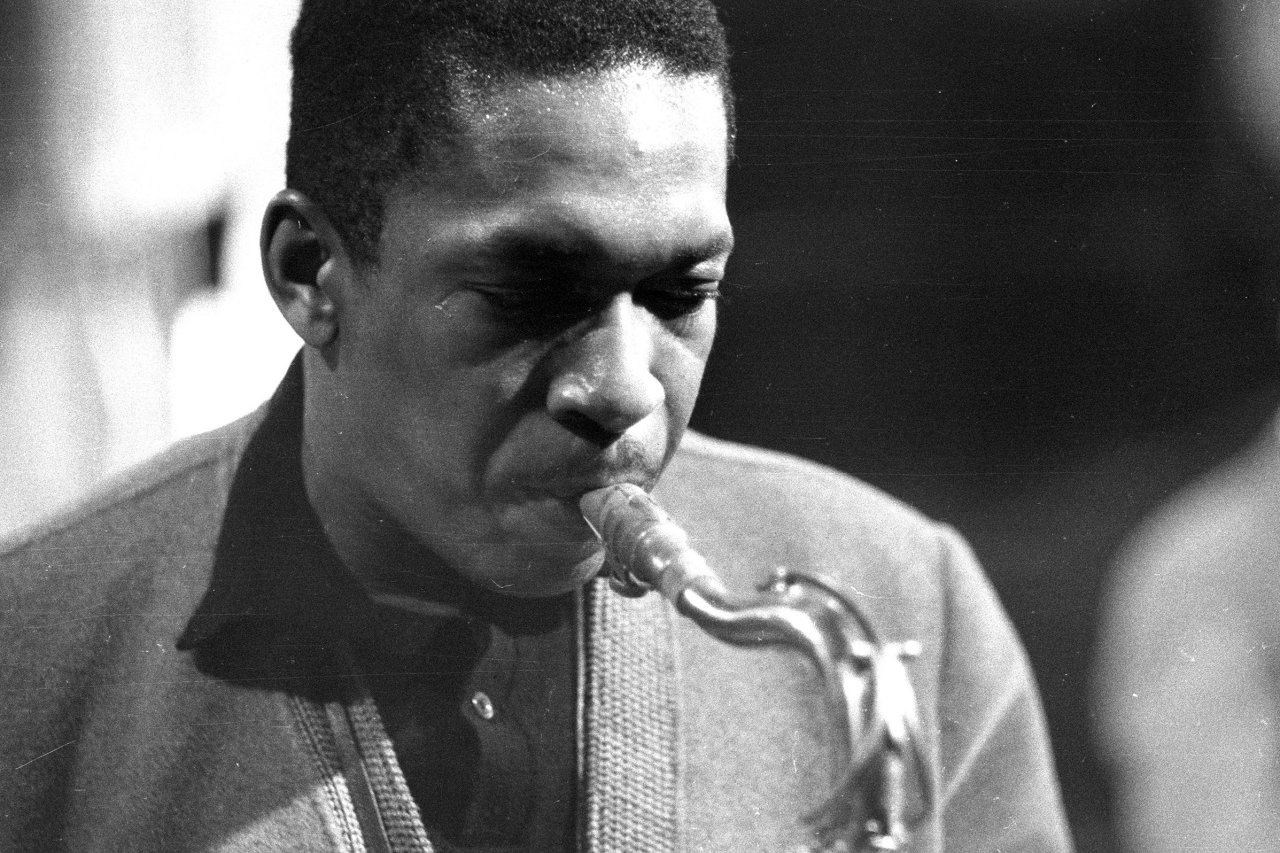

Almost exactly a half-century before this night, the not-yet-legendary John Coltrane had recited the same poem for the first time—also through his tenor. He was making a new album with a dream team of players later dubbed the "classic quartet": pianist McCoy Tyner, drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison. The poem served as the inspirational core for the fourth and final movement of a suite Coltrane had brought to recording engineer Rudy Van Gelder's studio in Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. In a marathon session that evening of December 9, 1964, the quartet laid down the 33-minute album that startled and redefined not only jazz but other genres. This month marks the 50th anniversary of the release of that recording, often cited as one of the most influential artistic statements of the 20th century. The poem, the suite and the record share the same title, A Love Supreme.

For its power and innovations in structure and improvisational style, A Love Supreme is a piece that serious players study and revere—but rarely dare to perform. The subject was almost shockingly personal for a jazz recording: Coltrane's offering of faith and thanks to God. In the liner notes he included the written version of the poem, which begins, "I will do all I can to be worthy of Thee O Lord."

Yet A Love Supreme quickly found a receptive audience far beyond jazz wonks and religion-minded listeners. Within a year of arriving in stores in late February 1965, the recording was named Album of the Year by DownBeat magazine and nominated for two Grammys. (The following year, Newsweek devoted six pages to the new "jazz revolution," identifying Coltrane as a leader.) It is one of the few jazz records to go mainstream, going gold (500,000 copies sold) years ago.

Ashley Kahn, author of A Love Supreme: The Story of John Coltrane's Signature Album, says the recording inspired new trends in music and performance, from the minimalist works of classical composers Steve Reich and Terry Riley to the trancelike live solos of the Grateful Dead and the Doors. Among those who have pointed to the record as a source of inspiration, according to Kahn, are REM guitarist Peter Buck, poet/singer Gil Scott-Heron, Joni Mitchell and Bono. A Love Supreme has also become a modern meme. As a prop in Don Draper's living room, the album cover's brooding portrait of Coltrane helps evoke the simmering mood of the Mad Men era. Now playing regularly in contemporary movie backgrounds and hipster bars, the recording's saxophonic keening reminds audiences that many of the old tensions are still on the stove.

It's a safe bet John Coltrane never set out to disturb the trajectory of music. Low-key and introspective, he plied a dedicated path from unremarkable beginnings in the Philadelphia music scene of the 1940s. Over the years, he added to his church and R&B roots by apprenticing with bands led by Johnny Hodges, Dizzy Gillespie, Miles Davis and Thelonious Monk. Through Davis, Coltrane got interested in tunes with fewer chords stretching over longer periods. With Monk, he studied a compelling combination of catchy, jagged melodies with bald dissonance. Drugs and booze knocked him off track more than once, but he was also hooked on conjuring a new musical vocabulary.

Through the late 1950s and early 1960s, Coltrane signed record deals and gained attention. His 1961 soprano sax recording of the Sound of Music song My Favorite Things became a hit with mainstream listeners. In other settings, discerning jazz buffs were alternately mesmerized and baffled by his feverish, improvisational explorations and what seemed like public practice sessions of weird scale exercises.

By late 1964, having battled back from a series of dark binges and committed himself to staying clean, Coltrane felt the need to signal his gratitude to the higher being who he believed had saved him. It was a perfect creative storm, an obsessive musical quest colliding with a fervent spiritual urge.

With all the dissection inflicted on A Love Supreme over the years by historians and musicologists, virgin listeners might justifiably gird themselves for a dry, intellectual oeuvre. But in this anniversary year, give it a chance. It will agitate your ears.

Drummer Jones opens the first movement with the crash of a Chinese gong, clearly signaling this is not your grandfather's jazz. Coltrane's vocal chanting of the phrase "a love supreme" is followed by his tenor mimicking the words over and over in ever-changing tonalities; it's hypnotic. Prepare to be shaken by frenetic blasts of his hallmark "sheets of sound," then soothed by the short, prayerful utterances of the final, poetic movement. The entire piece is propelled by elements of the blues—intuitive harmonic backdrops, infectious melodic hooks and irresistible rhythms. Above all, like indelible music of any style, it is a flood of emotion. The rule of thumb is two listening sessions. By the end of the second, most newbies are hooked.

"Fifty years later, you turn it on and listen," says Randall Kline, the SFJAZZ Center's executive artistic director, beaming. "It's as fresh as anything you might hear now."

"It's sacred music for us," says Ravi, thinking back to the performance that included his psalm-like duet with Lovano. "None of us had ever played it before in a performance. There was a message on that album, something for us to receive from John. But to perform it ourselves and to redo it—it was a bit delicate."

"The prayer we didn't even rehearse," recalls Lovano. "Ravi was just reading it, and I was just following and playing as if I was accompanying a singer. It felt really beautiful."

Remarkably, the younger Coltrane and his collaborators played a new, ovation-stirring interpretation of A Love Supreme on every one of the festival's subsequent three nights. A few days after the San Francisco tribute, he was back in New York rehearsing his regular quartet for a stretch at the Village Vanguard. No, he said, he had no plans to "take it on the road." But he was confident that others would commemorate the piece through the year, and predicted people would continue to listen "generation after generation."

To Kline, the power and longevity of the music comes from its double whammy of challenge and generosity. No doubt it's difficult at first—that is a saxophone reciting a psalm, after all. But isn't the challenge part of the lasting appeal? "This is a piece that people would use to work through whatever they were wrestling with," explains Kline, harking back to flower children and civil rights marchers, who both adopted the song as an anthem. Today its 50th anniversary arrives during another period defined by division and partisans turning a deaf ear. Think Michael Brown, Eric Garner, Charlie Hebdo...

"It's about listening," says Kline. "It's an invitation—and a means—to listen outside your comfort zone. This is a time when we really need something like A Love Supreme."