In June 2013, Darrell Fortner was in Denver, an hour's drive away, when one of the worst fires in Colorado's history bore down on his hometown of Black Forest, killing two people and incinerating 486 houses, including his. Also among the casualties were his four German shepherds and five cats. A year and a half later, he's trying not to cry as he stands next to the handful of graves that run along his property line. Their bodies lay buried in the ground, under a foot of snow, their final resting places marked by brightly colored artificial flowers and small white crosses.

Had he been home that day, when the flames tore through his community, he adamantly believes he could have saved his animals; his house; and the computers, 11 work trucks and equipment needed to run his tree-trimming business. Instead, Fortner, a broad-shouldered man with a big belly and a full head of white hair, is shattered by what he has lost.

Fortner is far from alone in his pain. As the Mountain West gets warmer and drier, there doesn't seem to be any end to what used to be called "fire season." In July 2014, the Carlton Complex Fire in the central part of Washington state burned over 250,000 acres and destroyed 300 homes. Containment costs have been estimated at more than $100 million. The year before, in 2013, California's Rim Fire outside of Yosemite National Park also burned over 250,000 acres, igniting 100 structures. The firefighting costs alone were upward of $127 million. June of that same year saw one of the deadliest fires in U.S. history: the Yarnell Hill Fire near Prescott, Arizona, which destroyed 157 homes and killed 19 firefighters.

Dangerous climate conditions are not the only thing to blame for these increasingly costly—and deadly—fires. For most of the 20th century, forest management meant suppressing every fire that ignited. In the long run, that policy led to overgrowth and tightly packed trees, which are much more prone to not only catching flame but burning with increased intensity. That's become a particularly troubling reality because, in recent years, a trend has developed among a certain segment of Americans to move out of cities and into the wilderness—an area known as the Wildland-Urban Interface (WUI)—where 10 million new homes were built between 2000 and 2010. These are people looking for solitude. Many don't realize, or perhaps don't care, that they've put down roots in the middle of a potential tinderbox.

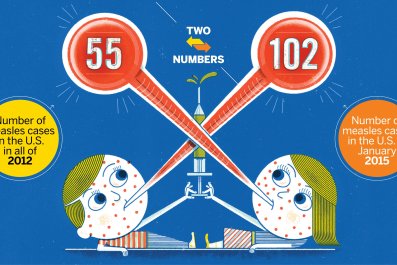

Protecting all this new construction, as well as the 37 million older homes in these areas, has caused the costs of fighting fires to soar. A report from the U.S. Department of Agriculture's Office of the Inspector General claims that between 50 and 95 percent of firefighting costs are directly related to protecting private property and homes in the WUI. In 2014, that cost totaled more than $3 billion—more than double what it cost to fight fires a decade ago.

But new residents of these WUI areas often don't think about fire when they move into their homes. There's a feeling that they paid for those trees—and the privacy provided—when they bought the property. So while local fire experts have made concerted attempts to educate people on how to protect their homes, many of their efforts are met with skepticism. "Mountain communities do things their own way," says Kathy Russell, a resident of Black Forest and a longtime volunteer with the local fire district.

Russell is also one of the lucky few whose houses survived the inferno. Well, it was part luck and part preparedness: Unlike many of her neighbors, she thinned back the trees on her property considerably, cutting down many of the smaller ones and removing the lower limbs from the bigger ones. When the Black Forest Fire burned through, "a 200-foot wall of flame came from the west side, but when it hit my property, it was forced to a slow crawl back on the ground," she says. "It went from catastrophic to inconvenient."

Fortner had taken precautions long before the Black Forest Fire. He'd been in the tree-trimming business for 20 years and understood the dangers of living in a forested area. He'd tried to reduce his risk by clearing away trees from his house and doing what he could to make his home more fire-resistant. But Fortner's neighbors weren't as diligent with their properties. Attempts by the county commissioners and the local fire board to pass regulations requiring the residents to thin their trees and fireproof their property have been met with staunch resistance. Even after the blaze, many locals remain almost hostile to the idea of fire preparedness; a recent push by the county commissioners to enact new, fire-resistant building codes was rejected.

"I think they're cowards," Fortner says, referring about the local government. "They don't have the backbone to [enforce a mandate]. Somebody needs to take control and say, Here's what's going to happen, we're going to protect the people and that's the bottom line." He's considering filing a lawsuit against the local fire board, as well as the state, for negligence.

In Black Forest, as in other communities across the West, there's a general distaste for any authority figure telling people to cut back their trees, let alone how to build their home, where to keep their woodpiles (not next to the house) or what to plant in their yards (native, less-flammable species). That's why Scott MacDonald, a former firefighter, doesn't think a top-down approach will work. "People will just dig their heels in," he says. Trying to force change could result in even more resistance—MacDonald believes people have to come around to addressing the risks on their own terms.

After leaving the fire department, MacDonald joined Black Forest Together, a nonprofit, grant-funded organization founded by the community's members to help them recover from this last fire—and prepare for the next one. He hopes his group's education and mitigation services will encourage a change in behavior. "When you move out here, you become a land manager," he says. Residents have to understand both the risks and the responsibilities, like clearing space around homes and thinning trees—not just once but repeatedly, over a lifetime.

A growing number of locals have expressed interest in taking action since the fire, but it's scattershot. MacDonald likens what's happening to sewing a community quilt: A couple of squares won't do much good on their own; to be useful, there have to be big, contiguous swaths. People need to be a little less independent and a little more open to working with one another. "You've seen the loss," he argues. "Work as a community and you can help yourselves."

Black Forest might learn from its mistakes. But Ray Rasker, executive director at Headwaters Economics, a nonpartisan economics research firm based in Montana, says the scope of the problem goes well beyond Black Forest. He points out that there are about 70,000 communities at risk from fire in the West. Of those, only about 2 percent have done significant work to reduce the potential of that danger.

To make a real impact, Rasker says, we need to start doing something about the areas that have yet to be developed. Drawing on input from rangers, fire marshals, ecologists and government officials from all over the Western U.S., he's developed a nine-point plan that would reduce the risk of wildfire by controlling the pattern of future development in the WUI. The most basic step: requiring counties to disclose the fire risk potential to homebuyers. That alone, he argues, will have people thinking twice about building in the WUI.

Other points in Rasker's plan require the political will to enact some unpopular regulations, like getting counties and local governments to pony up for their fair share of firefighting costs. Under the current system, as a fire gets bigger and bigger, it gets kicked up the food chain, from the county fire department to the state and, finally, to the federal level. After a major fire like Black Forest, the state can apply to the Federal Emergency Management Agency and get up to 75 percent of the cost of a fire reimbursed. And that means the bill is being footed by federal taxpayers, most of whom don't live anywhere near the forests of the West.

But in Western communities like Black Forest or Yarnell, Arizona, the decisions about land management and development are being made at the local level. And since the local governments don't have to pay the full costs of firefighting in these high-risk communities, there's no strong incentive for them to change the way they think about fire and land use regulations.

Rasker believes if local governments were required to pay more for the costs of fighting fires, decisions about who can build where (and using what materials) would be a lot more judicious. He points out that if you're a county commissioner and you're looking at a new map for a subdivision, you look at a long list of things—weed control, wildlife impact, sewage, water, sanitation services, roads, schools—before deciding whether to grant the permit. Not on that checklist: Can we afford our share of the potential firefighting cost?

"If it was," he says, "they would think long and hard."

Perhaps the only way to force local governments to consider the true costs of forest fires would be federal legislation that would place the costs at their feet. It's a solution that would be incredibly unpopular and, at least in the short term, a huge burden on local communities. But until there's a shift in who foots the bill, Rasker doesn't expect to see much change.

Any big changes will come too late for Darrell Fortner. He opened his tree-trimming business with just one truck and two chainsaws. He's now back to square one. At 71, the idea of starting from scratch is daunting. Reminders of the fire are everywhere: the twisted, melted engine of one of his pickup trucks, the immense pile of blackened wood in front of his neighbor's house, the heavy machinery slowly demolishing nearby acres of burned trees.

His new house, rebuilt just 50 feet northwest of where his old one stood, is fireproof, with a shale roof, stucco walls and nothing flammable within 30 feet. But it doesn't feel quite right, and he's not sure how safe it is, even now; he talks about giving up the forest life and moving to Florida. There's still more than enough fuel here for two more fires of the same size, and it's only a matter of time before another one scorches Black Forest again.