"I caused some slight argument with Leonard this morning by trying to cook my breakfast in bed. I believe, however, that the good sense of the proceeding will make it prevail; that is, if I can dispose of the eggshells." (13 January 1915)

So wrote Virginia Woolf 100 years ago, musing on her latest domestic experiment. This attempt to cook eggs in bed was a light interlude in what was to become one of the worst years of her life. Reading her letters and diaries recently in the London Library, I discovered a more playful side to the modernist writer, who we have come to think of as stern, humourless, even tortured. Virginia's daily journal and correspondence reveal a sensitive, perceptive young woman who loved a "debauch of gossip" with her friends. And this time in her life, January and February 1915, was a precious lull before the storm: one month later she plunged into a nervous breakdown so severe that she lost the rest of 1915.

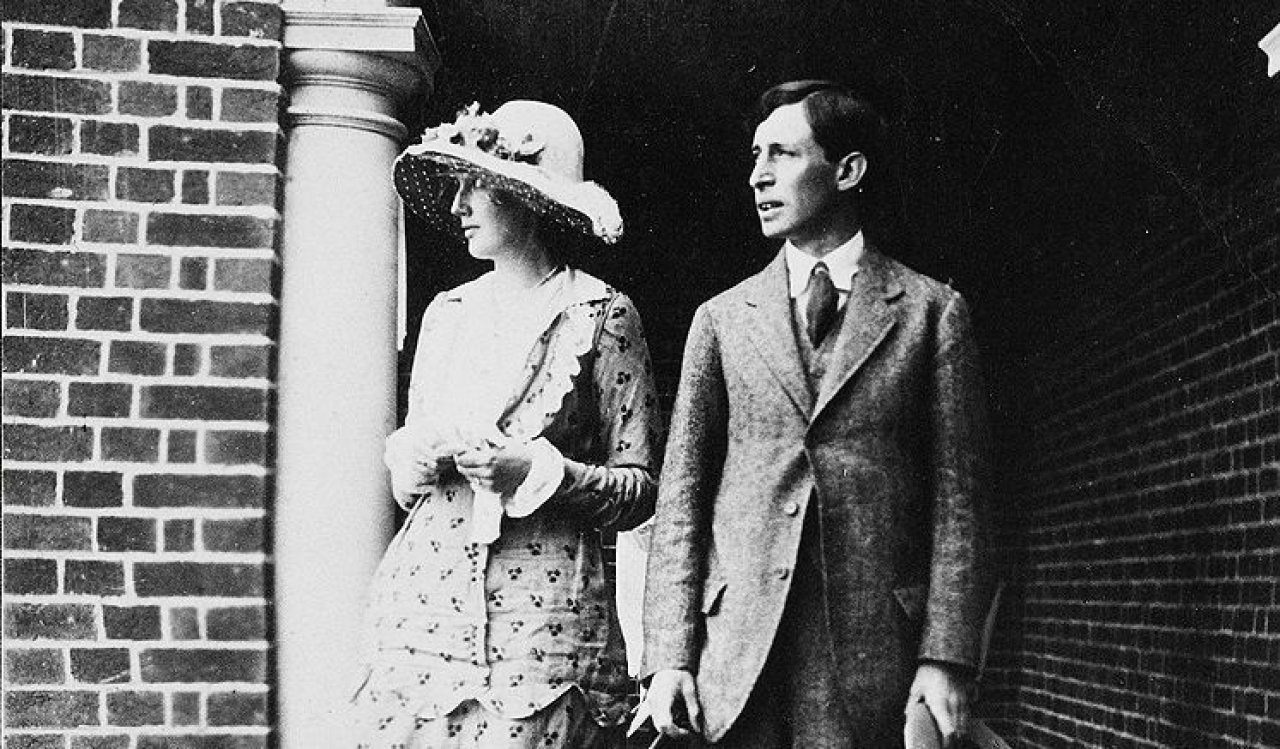

Sadly, these breakdowns were nothing new. The sudden death of her mother from rheumatic fever in 1895 had provoked Virginia's first breakdown at the age of 13. Her father's death in 1904 triggered her second collapse; her nephew and biographer Quentin Bell wrote: "All that summer she was mad." She also endured the death of her half-sister Stella in 1897 and her beloved brother Thoby in 1907; the repeated bereavements took their toll on her mental health. Virginia's third breakdown in 1913, aged 31, occurred less than a year after her marriage to Leonard Woolf.

Between 1913-15 Virginia made several suicide attempts, including trying to jump from a window and overdosing on Veronal, a powerful sedative. As the 'madness' took hold, she would stop eating or sleeping and at times she hallucinated – Bell records that she once heard "the birds singing in Greek and [imagined] that King Edward VII lurked in the azaleas using the foulest possible language". 1915 ought to have been a good year for Virginia. As well as the publication of her first novel, she was starting to make a living from reviewing and other critical writing. She and Leonard were living in Richmond, making plans to set up their own printing press, and discussing buying a bulldog, to be called John. So why did 1915 take such a disastrous turn?

She had been grappling with endless drafts of The Voyage Out for four or five years – Leonard recalled her rewriting it "with a kind of tortured intensity". It was finally published on 26 March 1915, the day after Virginia entered the nursing home where she was to remain for the next six months. The novel had been accepted for publication in 1913 (by her half-brother Gerald Duckworth, who is said to have sexually abused her as a child) but was delayed because of her hospitalisation. Throughout Virginia's life, the process of completing a book and working on proofs was a time of extreme anxiety, followed by the terrible wait for publication, and, still worse, the critical response. In 1936 while struggling with The Years she recalled the misery and self-doubt she had experienced two decades earlier: "I have never suffered, since The Voyage Out, such acute despair on re-reading . . . Never been so near the precipice to my own feeling since 1913."

Infinite Pleasure

It was appropriate that I was rediscovering my great-aunt's letters and diaries in the London Library: her father Sir Leslie Stephen was president of the Library from 1892 until his death in 1904. Virginia referred to it as "a stale culture smoked place" in 1915, although she was a regular visitor there. When the librarian showed me her original registration form, I was moved to see that she joined the library four days after her father's death. Despite being only 22 years old, she describes her occupation on the form as "spinster".

The joy of Virginia's personal writings is the lively and varied content, from literary highs to domestic lows, gossip about her contemporaries and relatives, often satirical, sometimes spiteful (especially about the "Jews", Leonard's large family). On the one hand she is writing to Thomas Hardy: "I have long wished to tell you how profoundly grateful I am to you for your poems and novels, but naturally it seemed an impertinence to do so." (17 January 1915). And in her diary at the same time she is documenting the daily catastrophes in their "House of Trouble" in Richmond: on a typical January day "the pipes burst; or got choked; or the roof split asunder. Anyhow in the middle of the morning, I heard a steady rush of water in the wainscot . . . various people have been clambering about the roof ever since. The water still drips through the ceiling into a row of slop pails."

The diaries also offer a fascinating insight into Virginia's early development as a writer: "I wrote all the morning, with infinite pleasure, which is queer, because I know all the time that there is no reason to be pleased with what I write, and that in six weeks or even days, I shall hate it." (6 January 1915.) But then, these reservations sound like the ups and downs of any writer, not a woman on the verge of a nervous breakdown.

According to those closest to Virginia, particularly Leonard and her sister Vanessa Bell, completing The Voyage Out was a major factor in her 1915 breakdown. So, what was in the novel to trigger such a collapse? There are many interesting parallels between the novel and Virginia's own life during the years she was writing it. Her heroine Rachel Vinrace, on a sea-voyage from England to the sultry South American jungle, is on a journey of self-discovery that mirrors Virginia's own transition from sheltered Victorian childhood in South Kensington to the intellectual and sexual liberation of Bloomsbury, where she moved with her siblings following their father's death. Similarly, Rachel's first steps into womanhood are echoed in Virginia's personal development: while rewriting The Voyage Out she would become engaged and then married to Leonard Woolf. Virginity, violation and fear of sexual intimacy are constant, uneasy themes in the novel, reflecting the anxieties of both heroine and author.

Hesitating throughout the spring of 1912 over Leonard's proposal, Virginia had struggled to reconcile "being half in love" with him with a sort of revulsion over "the sexual side of it". Writing to him a few weeks before they became engaged she explained what was holding her back: "As I told you brutally the other day, I feel no attraction in you. There are moments – when you kissed me the other day was one – when I feel no more than a rock." She hesitated not because she felt too little, but perhaps because she hoped for too much. "We both of us want a marriage that is a tremendous living thing, always alive, always hot, not dead and easy in parts as most marriages are. We ask a great deal of life, don't we?" (May 1912.)

Rachel Vinrace expresses similar sentiments, telling her prospective husband Terence Hewet: "I've cared for heaps of people, but not to marry them . . . All my life I've wanted somebody I could look up to, somebody great and big and splendid. Most men are so small." Like Virginia, Rachel admires her future husband, but she is also apprehensive about what is expected of her as a wife. It's no coincidence that shortly after Rachel accepts Terence she plunges into the tropical fever that will kill her. She suffers disturbing hallucinations: "While all her tormentors thought that she was dead, she was not dead, but curled up at the bottom of the sea." Virginia writes to Leonard: "I feel angry sometimes at the strength of your desire," and Rachel says of male sexual desire: "It is terrifying – it is disgusting." Whether or not Virginia had been abused as a child, it's no wonder that writing and rewriting The Voyage Out exacerbated her instability in the years leading up to its publication in 1915.

'I Want Everything'

There has been much speculation about the sexual dimension of the Woolfs' relationship: was the marriage ever consummated, was she frigid, was she a lesbian? In 1967 Gerald Brenan added fuel to the fire, writing: "Leonard told me that when on their honeymoon he had tried to make love to her, she had got into such a violent state of excitement that he had to stop, knowing as he did that, these states were a prelude to her attacks of madness . . . So Leonard had to give up all idea of ever having any sort of sexual satisfaction."

Can this be true? What did Virginia expect from their marriage? Before their engagement she wrote to Leonard: "I want everything – love, children, adventure, intimacy, work." She is often portrayed as unmaternal but this seems inaccurate. She adored looking after her sister Vanessa's children, and she and Leonard hoped for a family of their own, as this poignant letter in 1913 reveals: "We aren't going to have a baby, but we want to have one . . . " For me, one of the saddest insights in Virginia's letters and diaries is the profound sense of loss for the family they never had. She blamed herself for their childlessness, writing to a friend in 1926: "A little more self-control on my part, and we might have had a boy of 12, a girl of 10." However, it had been decided (by Leonard, Vanessa and her doctors) that Virginia was too unstable for motherhood – as her sister interferingly wrote: "The risk she runs is that of another bad nervous breakdown and I doubt if even a baby would be worth that." Given that not having children did not prevent her breakdowns, I often wonder whether it might have helped.

During 1910, 1912 and 1913, Virginia was sent for 'rest cures' in Twickenham to "a private nursing home for women with nervous disorder". As well as enforced seclusion, she was placed on a regime of weight gain; four or five pints of milk daily, as well as cutlets, liquid malt extract and beef tea. The recommendation from her psychiatrist was that a patient "who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing 12". This advice clearly made an impact on Virginia: she repeats it almost verbatim in Mrs Dalloway when the celebrated psychiatrist Sir William Bradshaw orders "rest in bed; rest in solitude; silence and rest; rest without books . . . so that a patient who went in weighing seven stone six comes out weighing 12".

Understandably, Virginia felt frustrated at being infantilised in this way, with all her decisions made for her. In 1912 she complained: "Leonard made me into a comatose invalid." This accusation is not without a degree of truth, he replaced the excitement and social whirl of Bloomsbury with the relative quiet of Richmond; he made her spend the mornings in bed, he monitored her eating and weight, her moods and menstrual cycles.

Leonard's insistence on rest and rich food continued throughout her life: shortly before her suicide in 1941 Virginia rages impotently in a letter to her doctor about "the cream, the cheese, the milk". However, she also knew that Leonard was right about the "danger signals". As she wrote to Jacques Raverat in 1922, "unless I weigh 9 and half stones I hear voices and see visions and can neither write nor sleep". And she knew that she owed Leonard her life, as she wrote in 1929 to her reputed lover Vita Sackville-West: "I should have shot myself long ago in one of these illnesses if it hadn't been for him."

Virginia Taking Off

Virginia's doctors insisted on "total rest of the intellect", so there are gaps in her letters and diaries during the "mad" times. Fortunately, Leonard, a former colonial civil servant, was a meticulous note-taker; his autobiography, Beginning Again (1911-1918) sheds much light on how and why her crises unfolded. It wasn't only Virginia's health that he documented; my father recalls working lunches with his uncle: "He went to the nearest bakery and bought two penny bread rolls and butter and sat on a park bench. He took out a black covered notebook and wrote down, "Two bread rolls. 2 pence". Everything was recorded. He recorded the score at bowls; he recorded the yield of every fruit tree in the garden." Another time, my father recalls TS Eliot saying: "Leonard invited me to lunch at Victoria Square, and all he gave me was a bag of chips and a bottle of ginger beer." In fact Leonard wasn't mean, just very careful with money – a character trait made famous by Virginia's announcement of their engagement: "I'm to marry a penniless Jew."

Comments like this, probably meant affectionately, have earned her the reputation of being snobbish, even anti-semitic. But what was Virginia really like? My father (who lived in Leonard's London home for 30 years) remembers his aunt as: "Volatile, mercurial, moody . . . She could be quite sharp – she looked sharp, her face was sharp. When you arrived at their house, she would ask you about your journey and she wanted every detail. 'Okay, you came by train. Tell me about the people in the carriage'." It was the novelist's search for copy, ideas. Leonard referred to this as "Virginia taking off".

My father recalls how she would recycle information: "You'd tell her something, a little story or an account, and the next week she would have built it into a big deal, exaggerating everything. By the time she'd finished the fictionalisation of an incident, it could be amusing but it could also be embarrassing for the person at the centre of things."

If 1915 was troubled for the Woolfs, Europe was also in turmoil. Although Virginia did not write directly about war, the conflict resonates through her novels, particularly Jacob's Room (1922) and Mrs Dalloway (1925) with their legacy of loss, shell-shock and a generation changed forever. The recurrent symbols of distant armies, bombs and guns overheard across the Channel in To the Lighthouse (1927) and The Years (1937) also have their origins in the First World War.

In January 1915 German strategic bombing had begun, with zeppelin raids over London. Most of Virginia's Bloomsbury social set were vehemently anti-war, including Maynard Keynes, Lytton Strachey – and Leonard who thought the war was "senseless and useless". Her brother-in-law Clive Bell's anti-war pamphlet was destroyed by the Lord Mayor of London, and her friend Bertrand Russell was imprisoned for pacifism. When conscription was introduced in 1916, Virginia wrote to a friend: "The whole of our world does nothing but talk about conscription, and their chances of getting off." Leonard did "get off", due to his shaking hands (a hereditary tremor) and his wife's mental instability.

Virginia's opposition to war was closely linked to her feminism: she described it as a "preposterous masculine fiction", and yet another outcome of male chauvinism. She wrote in Three Guineas (1938) that "the chief occupations of men are the shedding of blood, the making of money, the giving of orders, and the wearing of uniforms . . . "

The war features frequently in the wartime letters and diaries as a practical inconvenience as well as an ideological question. References to food rationing and shortages are mixed with newspaper headlines of naval victory: "We have sunk a German battle ship". And in November 1917 at the Battle of Cambrai, a single shell killed one of Leonard's brothers (Cecil) and wounded the other (Philip, my grandfather).

Hating the war, Virginia also detested the popular "Hang the Kaiser" jingoism of her compatriots, writing in January 1915 to the artist Duncan Grant: "They seem full of the most violent and filthy passions." In the same letter she mentions a Queens Hall concert "where the patriotic sentiment was so revolting that I was nearly sick".

The Printing Press

Despite the mounting casualties, and Virginia's uncertain health, those early months of 1915 record intensely happy times too. Her 33rd birthday, for example, when Leonard "crept into my bed, with a little parcel, which was a beautiful green purse . . . I was then taken up to town, free of charge, and given a treat, first at a Picture Palace, and then at Buszards [tearooms in Oxford Street] . . . I don't know when I have enjoyed a birthday so much." (25 January 1915.)

The final diary entries of 1915 are positively carefree. She describes a shopping trip after her skirt has split in two: Leonard goes to the library and she to "ramble about the West End, picking up clothes. I am really in rags. It is very amusing . . . I bought a ten and elevenpenny blue dress".

She muses on how London inspires her writing: "I had tea, and rambled down to Charing Cross in the dark, making up phrases and incidents to write about. Which is, I expect, the way one gets killed." (February, 1915). Two days later they went to see a printing press in Farringdon – delayed by Virginia's illness, they would finally set up the Hogarth Press in 1917, publishing T S Eliot, Katherine Mansfield, E M Forster and Sigmund Freud, among many notable 20th-century authors.

On 23 February Virginia suddenly became incoherent. Her letters a few days later refer to this brief attack: "I am now all right though rather tired"; "I am now well again and it is very wonderful"; "I have to keep lying down, but I am getting better." In fact, her health deteriorated further. At the end of February 1915 she "entered a state of garrulous mania, speaking ever more wildly, incoherently and incessantly, until she lapsed into gibberish and sank into a coma," (Bell). By March she was being cared for by professional nurses, and was unable to see or speak to Leonard – he writes that she was "violently hostile". At times her psychotic episodes were so severe that she required four nurses to hold her down, and there was genuine doubt over whether she would ever fully recover. She remained under professional care until November, when she finally returned to Hogarth House: "I spend my spare time in bed, but I'm allowed out in the afternoons, and thank God the last Nurse is gone."

Whatever the truth about their marriage, it was a partnership of great importance to 20th-century literature. Without Leonard it's unlikely that Virginia would have survived her suicide attempts of 1913-15, let alone stayed alive long enough to write Mrs Dalloway, To The Lighthouse, or The Waves, now considered seminal modernist texts. And there is no doubting the profound love between them.

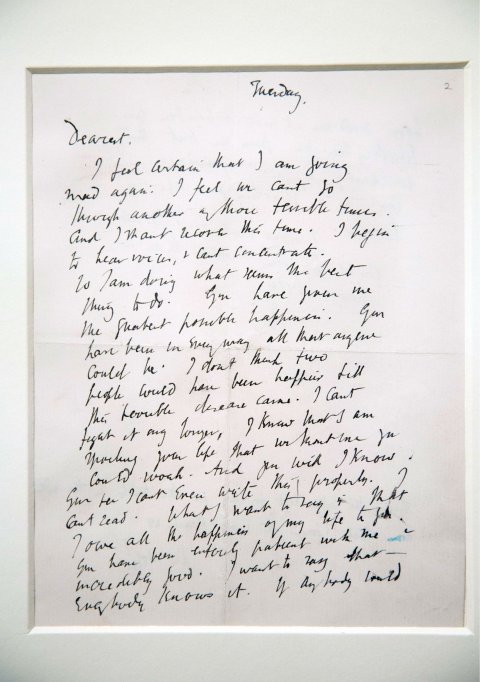

Virginia's suicide note to Leonard, written before she drowned herself in the River Ouse in March 1941 is testament to that closeness: "What I want to say is I owe all the happiness of my life to you. You have been entirely patient with me and incredibly good . . . I don't think two people could have been happier." This farewell is hauntingly foreshadowed by Terence's final words to Rachel on her deathbed, written 30 years before: "No two people have ever been so happy as we have been."

When The Voyage Out was published 100 years ago it was well received by the critics, although Virginia was too ill to know it. She wasn't present when Leonard formally registered her as an "author" a few days later. In January 1915, after a walk along the Thames (with her dog getting into a fight, and her suspenders coming down) she had noted: "My writing now delights me solely because I love writing and don't, honestly, care a hang what anyone says. What seas of horror one dives through in order to pick up these pearls – however they are worth it." In the end, Virginia's madness was part of the writing, and the writing was part of the madness. Perhaps the seas of horror were worth it for the pearls.