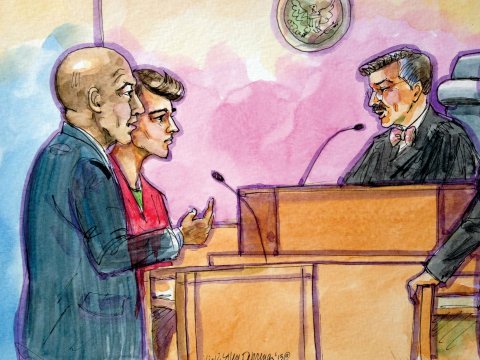

The clerk read each of the guilty verdicts, seven of them, while standing next to a large window that framed the Brooklyn Bridge in thin winter sunlight. That panoramic view will be one of the last Ross Ulbricht, who had just been convicted of multiple crimes, including narcotics trafficking conspiracy and money laundering, will likely enjoy for many years. The man who built Silk Road, the Amazon of what's often called the Dark Web, took his conviction stoically, then turned and smiled at his family and supporters—young men and women who distrust the government at least as much as Tea Partyers do.

As a federal marshal marched Ulbricht out a side door, a young man in black dreadlocks shouted, "Ross is a hero!" Derrick Broze, a member of the Houston Free Thinkers, came to New York for this trial, part of a group of self-styled anarcho-libertarians who squeezed into the courtroom every day. In the brush-cut precincts of the Southern District of Manhattan, they stood out with their dreads, vintage threads, tattoos, piercings and smoky odor, and they provoked the judge's ire when they distributed pamphlets to potential jurors urging them to declare Ulbricht innocent no matter what the evidence showed. They believe the government's prosecution of him is about something much bigger and more menacing than a simple drug trafficking case. They say it is an ominous triumph for the agencies that are spying on all of us, all the time.

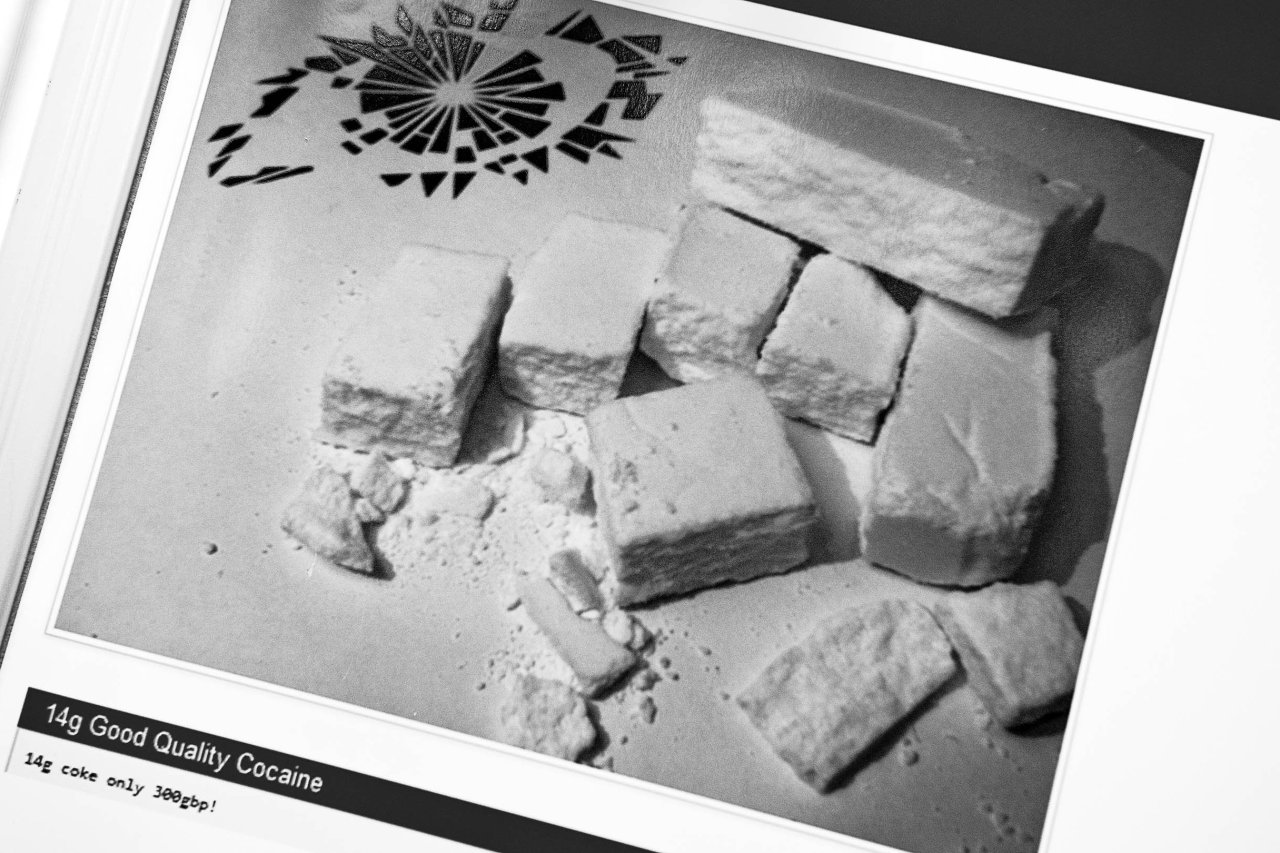

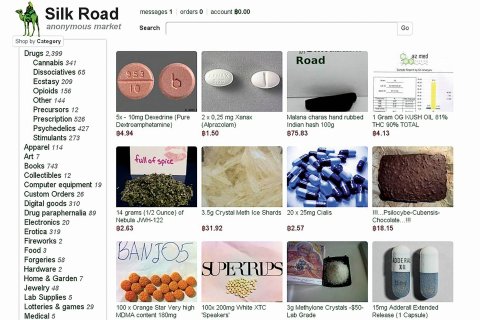

Ulbricht's exchange was the logical extension of Craigslist or eBay or Uber, a company matching customers with providers and collecting a fee, although in this case the buyers weren't seeking poodle ashtrays or a ride in a Prius. Silk Road matched drug sellers and drug users across the globe. If hailing a cab seems out of date, so too is walking around a city park hoping to score some weed.

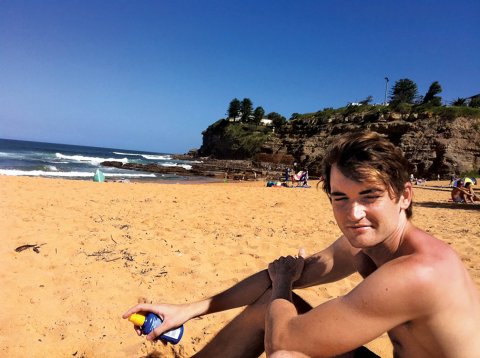

Even before he was arrested in October 2013, Ulbricht portrayed himself as more than a drug kingpin—a philosopher kingpin, perhaps. He is ambitious, creative, tech-savvy and a dead-ringer for actor Robert Pattinson. Before he found his inner cartel leader, he was more Haight-Ashbury than Silicon Valley, more 'shrooms than Sand Hill Road, more into Adam Smith than Steve Jobs. He fashioned himself a libertarian, perhaps a younger, hipper version of Mitt Romney in his early days at Bain Capital. A scientist and self-taught programmer, he left digital crumbs recording his progression from grad student to online drug lord on his computer; on YouTube and LinkedIn; and in chats and emails. His fatal error was thinking he could remain anonymous on the Internet—the same Internet that computer security writer Bruce Schneier has called "a surveillance state."

In the post-Snowden era, it is surprising to find smart people selling drugs online who think they are invisible behind a cloak of Internet anonymity. But most of us harbor similarly naive beliefs, such as a faith that a strong password, two-step verification and other bits of cyber-hygiene that we're told to practice as diligently as we brush our teeth allow us to roam the Internet safely. They won't. Ulbricht believed the so-called Deep Web would protect him. It didn't.

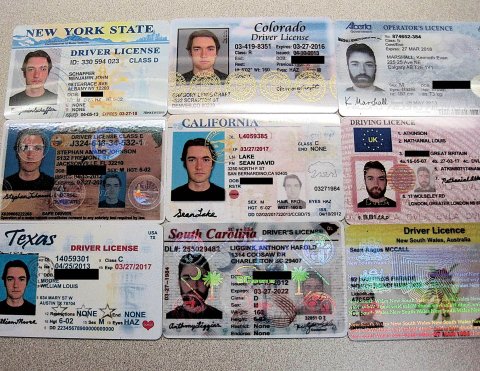

The stunning rise and sudden fall of Silk Road is a story so compelling it was optioned by Hollywood before Ulbricht was convicted. In its short life, Silk Road earned him something like $80 million, according to authorities, in commissions on sales of drugs, guns and other contraband until FBI agents nabbed him while he was tapping into the free Wi-Fi at a public library in San Francisco. Ulbricht's trial, concluded in Manhattan last month, revealed that he was brought down by an extraordinarily elaborate cat-and-mouse game involving a maze of false Internet identities, the betrayal of trusted friends and associates, and half a dozen fake murders.

An Anarchic Ayn Rand

Growing up in Austin, Texas, in the 1990s, Ulbricht didn't look or act like an aspiring cartel boss. He was, his father says, "a healthy, happy, unflappable Buddha of a kid," an Eagle Scout and honor student, a math whiz, and because his parents built bamboo solar-powered houses in Costa Rica, Ulbricht was weaned on la vida pura, playing in the jungle and surfing.

The Free Ross Ulbricht website extols their hero's humanitarianism (donations to prison reformers and the urban poor, water programs in Africa). It omits the heedless hedonism. One of his friends, René Pinnell, told Rolling Stone that when he told Ulbricht he had "dipped a toe" in drinking and drugs during high school, Ulbricht said, "I did, like, a cannonball ... in that department."

All those drugs—Ulbricht reportedly favored hallucinogens—didn't seem to dull his wits. His SAT scores got him a full scholarship to the University of Texas at Dallas, where he worked on organic solar cells, a burgeoning branch of green energy research that relies on polymers rather than traditional materials.

In graduate school, studying materials science at Penn State, he joined the College Libertarians and was a supporter of Ron Paul. By 2007, he was so deep into libertarian crank-dom (even the black-helicopter variety) that he answered one of presidential hopeful Mitt Romney's YouTube questions about America's greatest challenge with this YouTube reply: "The most important thing is getting us out of the United Nations."

Ulbricht's politics are rooted in the philosophy of Austrian economist Ludwig von Mises, who fell somewhere on the political spectrum between Ayn Rand and anarchy. Mises was beloved by neither Milton Friedman nor the socialists, but his unrelenting contempt for government interference in markets drew acolytes.

By 2010, Ulbricht had turned away from materials science and academia and announced on LinkedIn that he would be "creating an economic simulation to give people a firsthand experience of what it would be like to live in a world without the systemic use of force," by which he seemed to mean police and laws. Around the same time, according to federal prosecutors, he was consulting a guidebook called The Construction & Operation of Clandestine Drug Laboratories and had built a DIY "shroomery" at a remote cabin in Texas to grow hallucinogenic fungi that would be the first product he was going to sell through his economic "experiment."

While his 'shrooms sprouted, Ulbricht taught himself computer programming. When he got confused about coding, he called on an old college friend, Richard Bates, a programmer at eBay. Ulbricht's girlfriend and Bates were the only people he told about his project. He hid it on Tor (The Onion Router), a browser system invented by the Navy that relies on layers of computer routers and is now used by dissidents, drug sellers and pornographers to cloak their Web activities. He set up the site to accept the cryptocurrency Bitcoin, evading both banking and government oversight.

Timeline: Key Moments in the Life of Silk Road Creator Ross Ulbricht

Soon, Silk Road had vendors galore, and buyers were avidly building a ranking system to screen out the bad stuff, an echo of customer preferences on sites like Airbnb and Yelp. Ulbricht was getting rich, charging 10 to 12 percent on each transaction. He didn't dare flash his wad, however, so he lived ascetically in rentals, often with roommates. He ditched Bates and the girlfriend before the end of 2011, moving to Australia for a while and then San Francisco. He limited his splurges to a Thailand jaunt, where he indulged in "jungles and girls."

As his business grew, Ulbricht kept a journal—on his laptop, of course—sometimes sounding as if he was writing for the benefit of future biographers. In one long entry dated simply "2011," he described the early days of Silk Road. "Only a few days after launch, I got my first signups, and then my first message. I was so excited I didn't know what to do with myself. Little by little, people signed up, and vendors signed up, and then it happened. My first order. I'll never forget it. The next couple of months, I sold about 10 lbs of 'shrooms through my site."

Later, in a chat, he joked that he wished he could explain Silk Road to family and friends who couldn't understand why an apparently unemployed young man was so busy: "I'm running a multimillion-dollar global drug operation!"

In addition to the diaries, he saved his chats, kept an Excel spreadsheet of his business and a Bitcoin "wallet" with $18 million on his laptop.

The money was nice, but Ulbricht constantly portrayed Silk Road as a political act. He told Forbes, in a blind online interview, that the site was "a way to get around the regulation of the state." On the site, he often issued "proclamations" like: "Silk Road is about something much bigger than thumbing your nose at the man and getting your drugs anyway," he wrote in 2012. "It's about taking back our liberty and our dignity and demanding justice." Some people give money to the American Civil Liberties Union; Ulbricht tried to start a revolution.

A Silk Road vendor who went by the online name "Variety Jones" picked up the banner. Jones, who advised Ulbricht to start using the handle Dread Pirate Roberts on the site and in his business communications, has never been publicly identified. He once wrote on a forum, according to Wired, "I'm here to break the back of prohibition, to make the jack-booted thugs from the DEA roll up their tents and sneak off into the night, and to do what I can to ensure a future where 65 year old MS patients aren't shot by SWAT teams during drug raids because they suspect there was a fucking plant growing in the back room."

As his site grew, the government took notice, and Ulbricht impishly reveled in the attention. As some U.S. senators called for Silk Road to be shut down, Ulbricht made a chipper comment to Bates in a chat about how yet another national media outlet had mentioned his grand blow for freedom. Meanwhile, federal agents in Maryland and Chicago were on his trail. Homeland Security agents scanning incoming mail on foreign flights started noticing hundreds of carefully wrapped small shipments of drugs—two or three Ecstasy pills—in envelopes with "StudyAbroad.com" return addresses and slips of paper inside, urging recipients not to forget to give customer feedback. By July 2013, the feds were so inside the Silk Road system that an agent was able to assume the online identity of a member of the Silk Road staff.

Ulbricht's success brought myriad challenges, not the least of which was hiding the identities of vendors and customers. In March and April 2013, prosecutors say, Ulbricht solicited the murder for hire of "FriendlyChemist," a vendor who was demanding a half-million dollars not to reveal the identities of some Silk Road vendors and suppliers. A few days after the threat, another anonymous user, "redandwhite," contacted DPR (Dread Pirate Roberts) claiming to be the person "FriendlyChemist" owed money to, and eventually agreed to commit a murder for hire for DPR. Prosecutors claim Ulbricht paid a total of $730,000 to kill FriendlyChemist and five more individuals who had threatened to reveal vendors' and clients' real names.

Silk Road came to its dead end on the afternoon of October 1, 2013. Federal agents had trailed Ulbricht from his modest house to the library, and arrested him while he was chatting online with what he thought was one of his employees, who was, in fact, an FBI agent sitting nearby. With Ulbricht logged on to his computer at a table in the science fiction section, two agents pretended to have a loud domestic spat behind him. When Ulbricht turned to watch them, a third agent leapt onto his open laptop, making sure he couldn't close it. Had Ulbricht been able to shut that encrypted machine, investigators would never have been able to access its contents, establish that he was the man behind the empire, or prove that he was the mysterious Dread Pirate Roberts.

Devastatingly Disloyal

Ulbricht's trial was a tragic spectacle, from the squandered brilliance of the young defendant to the haggard faces of his parents sitting behind him and the spectacular betrayal by his good friend Richard Bates. When defense lawyer Josh Dratel accused the eBay programmer of cutting a deal to testify against Ulbricht in order to avoid criminal charges, Bates, fighting back tears, conceded he had done just that.

Prosecutors projected chats between the two men on a giant screen in the courtroom, casual conversations in which Bates called himself "baronsyntax." The two young men chatted about programming code and parties and all the media attention Silk Road was getting. Ulbricht confessed at one point that he was "overwhelmed." (He was once so addled from stress—or the testing of his 'shrooms—that he forgot Bates had helped him move into a new apartment.) In November 2011, Ulbricht told Bates he had sold the site, and he drifted out of Bates's life. But Ulbricht had only gone dark and had a new set of online advisers and fans, some of whom would prove to be devastatingly disloyal.

The trial revealed some, but not all, of the tricks FBI agents used to snatch Ulbricht out of the Dark Web. First, agents hacked into Silk Road after locating its servers in Iceland. The government has never explained how it located those servers, at least to the satisfaction of tech experts. Once inside the site, government agents created fake personas to interact with the site's administrator. In the summer of 2013, one agent wormed his way into the top levels of the Silk Road operation, posing as an employee who went by the name of "Cirrus." Once the FBI was dealing directly with Ulbricht through false identities, it was only a matter of time before they smoked out his identity and whereabouts.

After they charged Ulbricht, FBI agents built their case by gathering metadata, trawling through his personal email, chats, photographs and Dread Pirate Roberts's chat logs. They matched known events from Ulbricht's life—an illness, a case of poison oak, an OKCupid date with a woman named Amelia—with mentions of the same events by the virtual DPR. By the time they were done, Ulbricht was ensnared by his actions and words online.

You Could Be Next

Ulbricht's supporters argue that his prosecution is about something a lot more important than Silk Road. They believe it's indicative of a rapidly spreading erosion of civil liberties—and they're not the only ones who believe that. Gizmodo writer Kate Knibbs wrote after the verdict, "[L]aw enforcement was allowed to present damning digital evidence without explaining where it came from. That's bad news for our civil liberties."

The Deep Web has many legitimate users. Library card catalogs and medical records have a home on it. Mainstream Internet users concerned about corporate invasions of privacy use it. Tor hosts a New Yorker magazine whistle-blower site, Facebook has established a special Web address for Tor users, and British rocker Aphex Twin recently released new music on it. Crucially, people living under tyrants find a home on it.

"We do know there are dissidents in Syria and Russia who use a forum that's hosted on the Dark Web to be able to communicate with each other secretly," says Jamie Bartlett, author of The Dark Net and director of the Centre for the Analysis of Social Media. "How do you weigh the life of a Syrian dissident against the ability to access pornography? You can't have the one without the other."

After the feds smashed up Silk Road, new black market sites sprouted on the Dark Web like 'shrooms after a soaking rain. Many of them are much more sophisticated, having learned from DPR's mistakes. The Web may be the future of the drug trade, just as Internet commerce has destroyed brick-and-mortar retail in other sectors, but the Silk Road investigation resembled the gritty cops-versus-gangs saga depicted in The Wire. "Despite all the obscure technology, old-fashioned policing is how they caught him," Bartlett says. "The answer to the problem of the Dark Net markets is going to be increased reliance on what you might consider good old-fashioned policing."

Ulbricht's supporters have a name for this kind of policing: entrapment. After seizing those servers, FBI agents impersonated vendors and employees to snare DPR. Those murders for hire that Ulbricht allegedly ordered turned out to be another elaborate ruse. No one has yet explained who was behind them, but Maryland federal prosecutors have indicted Ulbricht on one charge of hiring a federal undercover agent to commit murder.

Joshua Dratel, the defense lawyer, tried to convince the jury that anyone could find himself monitored by the government online, and that the chat logs purporting to involve Ulbricht under the Dread Pirate Roberts pseudonym could have easily been fabricated. "The Internet is not what it seems," he warned in his closing statement, reminding jurors that FBI agents assumed multiple fake online identities to catch Ulbricht and controlled "dozens of accounts" on the site—all without obtaining a warrant. "No one told anyone when he assumed new identities," Dratel said. "The Internet permits and thrives on misdirection and deception. Even the [FBI agent who posed as a Silk Road employee] said [the ruse] was so convoluted he couldn't keep track."

Dratel also argued in court that the FBI probably had help from an agency, like the National Security Agency (NSA), in locating the servers in Iceland. In a court filing, the government denied that. "Ulbricht conjures up a bogeyman—the National Security Agency.... The facts are not at all what Ulbricht imagines them to be.... The Silk Road server was located not by the NSA but by the Federal Bureau of Investigation...using perfectly lawful means."

But government agencies do share surveillance data from the Web; collaboration between intelligence agencies has been standard procedure since soon after 9/11. And given the magnitude of the FBI's domestic surveillance power, it's surprising it took the bureau two years to nail Ulbricht. Shane Harris, in his 2014 book @War: The Rise of the Military-Internet Complex, details a symbiotic relationship between the FBI and NSA, claiming that together they are shredding online anonymity. He reports that while the NSA pays phone and Internet companies to build their networks so that the agency can tap into them, and has deliberately weakened cryptographic standards and worked to break Tor, the FBI is the agency that enables the national intelligence agency's domestic operations. "When journalists say the NSA 'spies on Americans,' what they really mean is that the FBI helps them do it, providing a technical and legal infrastructure for domestic intelligence operations."

Schneier, the national security technology expert and blogger, is extremely bleak about online privacy. "Welcome to a world where Google knows exactly what sort of porn you all like, and more about your interests than your spouse does," he wrote in a blog post six months before Ulbricht was arrested. "Welcome to a world where your cell phone company knows exactly where you are all the time. Welcome to the end of private conversations, because increasingly your conversations are conducted by e-mail, text, or social networking sites. And welcome to a world where all of this, and everything else that you do or is done on a computer, is saved, correlated, studied, passed around from company to company without your knowledge or consent; and where the government accesses it at will without a warrant."

In other words, they did it to put Ulbricht in jail. You could be next.

Dratel told Newsweek the government's reliance on metadata bodes ill for defendant rights because it is easily manipulated. All of those coded bits of information—the time stamps and GPS stamps on photos and messages—can be easily manipulated, even forged. Lyn Ulbricht still denies her son participated in those incriminating chats with Bates and Variety Jones and the fake assassins. "There is no proof of who is behind that computer screen, or if it's one or more people using that name," she wrote in an email to Newsweek. "When everything is anonymous, identity becomes impossible."

The young philosopher kingpin who freed drug users from the locavore 20th century model of drug selling—street corners, landlines, bike messengers—is now paying for that with his own liberty, and facing a future his mother calls, simply, "grim."

Along with his supporters, Lyn Ulbricht will always see her son as more than just the audacious founder of a global drug eBay. "Internet freedom, the drug war, even liberty," she says, "are all on trial along with Ross."