House of Earth

There are two lines of poetry chalked along a beam in a simple, three-room house in the village of Yandoumbé in the Central African Republic:

Here I lie in house of earth /

Waiting for an upper berth

On any given night, at least five people lie within sight of that couplet – two on a low bed, beneath a tatty mosquito net, and, usually, three others on a naked foam mattress in the corner of a cement floor. Across the room there are two plastic tanks of water pumped from a nearby well and a couple of wooden chairs that tend to sit wherever they have been dragged by their latest occupants. The roof is made of palm fronds and many Westerners, if they saw the structure at all, would call the house a "hut" or a "shack", even though it is the largest and most solid construction in the area.

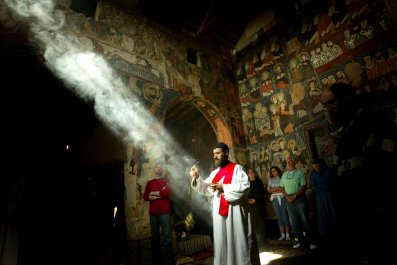

During daytime, sunlight spears through hatches swung open in the walls, while at night the pitch darkness of the African rainforest is broken only by small fires smouldering to ruin outside, or a kerosene lamp and battery-powered torch-cum-lantern propped on a hand-made desk.

If one looks closely, the light might also catch some writing implements and pots of herbs and spices amid the clutter on the table, as well as a couple of book spines, including the Oxford Dictionary of Music, close at hand. There are some spectacles hanging from nails driven into the wall and a small set of speakers wired either to an MP3 player or a radio.

The lines of poetry on the wall above are often cast into shadow, but even if they were perfectly illuminated only one of the permanent residents of the house could read them, much less understand the sentiment they express.

Their author is Louis Sarno, born in New Jersey in the United States in 1954, whose native language is rarely spoken in the village he has made his home. Yandoumbé lies more than 500km from Bangui, capital of the Central African Republic, and about a mile along what passes for a road from Bayanga, the nearest town that might feature on a map of one of the poorest nations in the world: the Central African Republic ranked 142nd of 142 countries on the 2014 Global Prosperity Index.

Yandoumbé is surrounded by the dense rainforest of the Dzanga Ndoki National Park, put on the Unesco World Heritage List in 2012 and not yet depleted entirely beyond function by the international logging market. It is clinging on despite widespread destruction in the region, and remains a haven of tropical flora and fauna, including forest elephants and critically endangered western lowland gorillas.

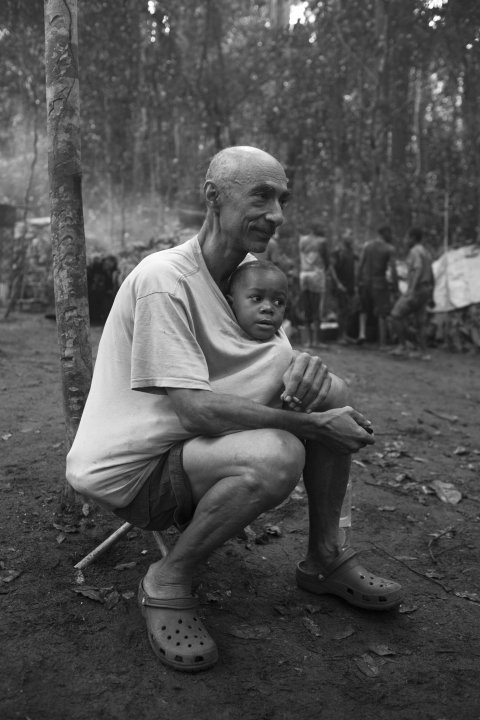

With the exception of Sarno, who is a wiry, 6ft-tall white man, each of some 600 residents of Yandoumbe are Ba'aka — or pygmies — a hunter-gatherer people indigenous to the Congo Basin. They include Sarno's girlfriend, Agati, and the three children who occupy the foam mattress in his home.

Nearly 30 years ago, Sarno was a wanderer, living between Amsterdam and Scotland, when he first heard the polyphonic singing for which the Ba'aka have a reputation that travels far further than the rainforest canopy. He was lured to the music's source clutching a microphone, a tape recorder and as many batteries and cassettes as he could carry. To all intents and purposes, he never came back.

Sarno has been described by some as the "white pygmy of Yandoumbé" or "Ba'aka Louis"; others have reached for the easy pejorative "Screwy Louis". But to some musicologists, Sarno is regarded among the most significant sound recorders in the world, a man who has amassed a peerless aural document of some of the most sophisticated music produced by man.

He is in demand in Oxford, Berlin and New York, and sometimes bows to the callings of academics or film promoters, making the four-day journey away from his home to some of the world's most prestigious institutions. Earlier this month, he took that journey once more and headed to the east coast of the US, where a new documentary about him, Song From The Forest, received its general release. He caught up with old friends, had health checks and attended interviews, in support of both the film and the re-release of a memoir he wrote in the early 1990s. But, as usual, his mind was never far from Africa.

Day to day, Sarno fills the role of village doctor, schoolteacher, advocate, interpreter, archivist, writer and fixer. Although his reasons for visiting, staying and eventually settling in Yandoumbé have shifted throughout the years, they are now principally to be found sleeping on those two beds in his simple house. Sarno is a doting husband and father, whose home has become a refuge to many.

Sarno will also, he concedes, most likely be elevated to his upper berth from this modest dwelling. He is 60 years old in a village where life expectancy is barely 40. What he describes as his "beloved Centrafrique" is gripped by a bloody civil war that has, by conservative estimates, already cost around 3,000 lives and forced more than 400,000 people from their homes. In the past two years, it has meant that Sarno, too, has been a refugee, fleeing against his will to the US, as well as finding himself a reluctant mediator between his people and the generals of the lawless forces who have plunged the Central African Republic into its crisis. Sarno has found flattery and massaging of would-be warlords' egos to be an effective strategy in preventing them murdering his family.

I first met Sarno in Oxford in April 2014.He was the guest of the Pitt Rivers Museum, the institution at which his extraordinary collection of field recordings has created a buzz among ethnomusicologists. Over the past 10 years, the Sarno collection of more than 1,400 hours of music and soundscapes from the Congo Basin has been digitised at the museum, offering future generations an unprecedented sonic insight into a bewitching musical world.

We also spoke in London, where Sarno was recuperating after a major health scare that required emergency surgery, and then months later in Berlin, where he had travelled to promote Song From the Forest's German release. I accompanied Sarno on the tortuous journey back to Yandoumbé from Europe, during which he shared the countless tales and boundless knowledge accrued during his remarkable life.

Sarno shies away from portrayal as a sage. He is uncomfortable with being depicted as dispensing worldly wisdom from a lofty moral perch beneath the rainforest canopy. But he has managed to make real what for so many disillusioned Westerners is only an idle dream: switching off, dropping out and creating a life immersed in one of the world's natural paradises, surrounded by exceptional music and song. Almost everybody I talked with about Sarno, across three continents and countless walks of life, used the same phrase to describe him.

"He's the real deal," they said.

New Jersey to Africa

Louis Sarno has described many times what led him to the rainforest, including in a tight précis at the start of his 1993 memoir Song From The Forest – My Life Among The Ba-Benjellé Pygmies. "I was drawn to the heart of Africa by a song," the book begins.

The author's photograph in the first American edition shows Sarno inside a mud hut, headphones over his ears, fiddling with some recording equipment and flanked by three athletic African men.

Although this memoir is due to be re-released this year amid the flurry of recent interest in Sarno, he disowned it for many years, citing the clichés it peddles about African adventure. He says that the book's young author, a fresh arrival to the rainforest, with black hair, bushy eyebrows and a keen glint in his eyes, knew almost nothing of the world he professed to describe.

Sarno is equally dismissive these days of his life before the point that it swerved towards Africa. It followed an unremarkable path from suburban New Jersey through unhappy college years and eventually to Europe, until the chance encounter with pygmy music prompted an epiphanic awakening and sent him even further from his childhood home.

Sarno was born to a second-generation Italian immigrant family in Newark in 1954 and enjoyed what he describes as a regular upbringing of "back yards and front lawns". His father was a high school maths teacher, and Sarno has two brothers and one sister. "We could climb over fences and go in each others' back yards," he says. "We had a whole neighbourhood to play in. I used to think of these little patches of woods as 'the jungle'. It probably inspired me. It partly inspired my liking the rainforest."

After graduating from high school, Sarno spent a year at Northwestern University in Chicago, where he first became friends with a young journalism student and future film-maker, Jim Jarmusch. But as Jarmusch neglected his journalism studies in favour of poetry and Sarno grew disillusioned with life in the Midwest, the pair soon transferred back to the East Coast and became immersed in the burgeoning avant-garde art scene in Manhattan and beyond. Jarmusch found a home in the English department at Columbia University, while Sarno enrolled at Rutgers, the state university of New Jersey.

Sarno also continued to grow a vast collection of classical music, which had been a passion since his youth, with a particular focus on the polyphonic singing of the Renaissance. Despite spending as much time in the city as he did on the college's New Brunswick campus, he eventually left Rutgers with a degree in English. He then spent three years in a post-graduate comparative literature programme at the University of Iowa.

Sarno met Wanda Boeke, a Dutch-American woman who became his first wife. The couple moved to Amsterdam, where Sarno worked in a succession of odd jobs, and he also accompanied Boeke on her regular trips to visit family and friends in Scotland. "I got to know this group of eccentrics up in Scotland, who had done all these travels," Sarno says. "They had gone to Afghanistan in 1960. It was a different world back then. Back then, I thought of Afghanistan as a place where they had the most amazing crafts … That's what Afghanistan used to mean to me – and the music. I had a couple of records of traditional music from Afghanistan, wonderful music too."

Having abandoned his collection of classical music in the United States, Sarno says he didn't have the heart to start building another in Europe. Instead, he found himself listening to the radio one day when he encountered a song that originated in Africa. "It just shot me off in a different direction," he says. "In the end it was the music of the pygmies that really attracted me, not just because of the music, but because of the environment. I found over a couple of years I got every available recording of pygmy music, even stuff that was out of print. I've always liked forests and I figured I had to go and make my own recordings. It became an obsession. I would go because I had all the music and I wanted more. It wasn't enough for me."

When his friends from Scotland next visited Africa, Sarno accompanied them with a loose plan to navigate from Tangier to the central African rainforest, recording music along the way. His first two attempts at finding the source of the pygmy music failed, but Sarno remained committed to the task. "Eventually I just picked the capital that was closest to the rainforest, which was Bangui, and I flew there," Sarno says.

Other aspirations, including to become a science fiction writer, were pushed aside. He also separated from his wife. He says he never expected that he would not remain in the rainforest permanently, but adds: "I did kind of have this vision of me living with the Ba'aka, with some group of pygmies. I did have a flash, when I first got a record out from the library and was listening to it, I had this kind of flash that I was going to be with them, living with them."

Jarmusch, who remains a close friend, says, "He's not someone who was going to find a job in an accounting firm or anything, and that was obvious from the first time that I met him."

The glow of little fires

One of Louis Sarno's earliest, aborted trips to Africa foundered when he was denied passage across what is now South Sudan by the outbreak of the second Sudanese war in 1983. The frustrations of the naïve young traveller, denied the opportunity to travel up the Nile into the Ituri rainforest, prefigured almost all more recent attempts to cross northern and central Africa, as a series of conflicts have brought vast swathes of the continent to its knees.

Last time Sarno made the journey home to the Central African Republic, it was with his eldest son, Samedi. They were coming home from Germany, where he had been touring to promote the documentary. Song From the Forest, which takes its name from Sarno's memoir, is directed by the German journalist Michael Obert and is framed around Samedi's first trip out of Africa in 2011, when he was 13, to visit his father's former life in New York.

After a drawn-out post-production process, the film had its premiere in Berlin in late summer of 2014 and Sarno and his son had been the guests of honour. The film was also shown at film festivals in London and New York in autumn and had its general release in the United States in early April.

I met Sarno and Samedi at Ataturk Airport in Istanbul, finding them close to the boarding gate for a flight to Yaounde, the charmless capital of Cameroon. Overland travel out of Bangui is now impossible and the safest route towards Yandoumbé, Sarno's tiny village close to Bayanga, demands a drive along the solitary road crossing Cameroon's southern districts. The Foreign Office is unequivocal in its advice against all travel to the Central African Republic but the Dzanga-Sanga National Reserve, which occupies the far south-western corner of the country, flanked by Congo-Brazzaville and Cameroon, has avoided the very worst of the bloodshed.

For Sarno and Samedi, of course, their reason for travel was simple and non-negotiable: after three weeks on the road, they were finally going home. Samedi looks younger than his 16 years. He was wearing a grey, long-sleeved T-shirt, blue jeans and blue-grey sneakers when we met at the airport and nobody in the departure lounge could have identified him as a pygmy, particularly when accompanied by his father. Sarno is tall and lean and at times can also pass for younger than 60 despite hair now reduced to grey wisps, and weary eyes. He wears a thin moustache along his top lip and props spectacles on his nose to read.

He alternates seamlessly between what remains recognisably an accent from the East Coast of the United States and Yaka, the dialect of the pygmies, which is not recognisable at all to Western ears.

A seven-hour flight to Cameroon was the easy part of a four-day trip. After a night in a grotty hotel in Yaounde, Sarno and Samedi had to pay a visit to the German consulate to confirm Samedi's return to the country. Sarno adopted Samedi after the boy's natural father was gored by a bongo, a rare but dangerous antelope indigenous to central Africa, in the kind of accident that can be a daily hazard in the rainforest. Sarno was in a long relationship with Samedi's mother, Gouma, and is named as Samedi's father on his birth certificate, obtained for the first time when Obert's film took them to the United States.

Eventually, after a swift visit to the market so that Samedi could buy a football, we hit the road east in the direction of the town of Bertoua. The roads in southern Cameroon, particularly east of Bertoua, exist only to service the lumber industry that tears away approximately 1,800 square kilometres of rainforest per year. Small villages have grown up alongside the road, but the men sitting beneath communal shades and the women crouched over cooking pots or scrubbing laundry in creeks seem of secondary concern to the never-ending convoy of trucks trundling metres from their homes. Each typically carries three enormous trunks of African mahogany, roughly 30ft long and six feet in diameter, towards Douala, Cameroon's western seaport. Groups of young children, who sometimes wander in hand-holding chain-gangs along the road, barely notice as the monstrous vehicles terrorise past, their insatiable demand for tropical hardwood carrying away the region's future prosperity.

Although Sarno's location has been remote for 30 years, he is not a recluse. In the past few years he has travelled away from his home more frequently than during any other period: to the United States for filming Song From the Forest, twice to Oxford to work on his collection of recordings, then back to Germany for the film's first promotional tour. He also fled the Central African Republic during the worst of the troubles in early 2013.

As we were stopped and harassed at checkpoint after checkpoint, Sarno talked about some of the methods by which he used to bribe his passage past the similarly corrupt road guards of the Central African Republic – a gift of a magazine or newspaper often enough to see his through. This time around, with the region jittery owing to the war, there was the feeling of having entered a different era. The guards seized on any perceived infractions in our paperwork – I had to cough up 10,000 Central African Francs (about 18) as a bribe because of the absence of proof of a polio vaccine on my medical forms – and Sarno was taken aback by a guard near the border's plaintive appeal: "Didn't you remember anything for me from your trip?" Sarno explained that his priorities were with his family, but parted with a soundtrack CD from Song From The Forest, a few copies of which he was bringing home for personal use.

Worse was due to come. We had heard along the road that the border patrol officer in Libongo, on the Cameroon side of the Sangha River, who would need to stamp our passports to allow passage to the Central African Republic, had recently been fired for punching a white man.

As we trundled into Libongo, however, Sarno's mood brightened. We pulled up at a shop owned by a Mauritanian friend and Sarno immediately saw that his current girlfriend Agati, with whom he has been in a relationship for three years, had come over the river and waited in the shop to meet us. We went through the formalities with the new border patrol officer with a minimum of fuss (nobody was punched) and, as dusk began to fall, stepped into a long, narrow pirogue that would ferry us to the real rainforest.

The first rain of the day arrived as we made our way across the water. The gods of travelogue cliché also delivered a rainbow stretching above the wall of forest on the eastern banks of the river. Another canoe appeared alongside us, paddled by a fisherman wearing an orange T-shirt and with a cigarette hanging from his bottom lip. He offered us two limp creatures; perhaps the last of his haul from the day, or its total. Suddenly, though, he halted the sales pitch to bellow: "Monsieur Louis!"

Sarno transformed miraculously from grouchy traveller to effusive tour guide.

He said proudly that the Central African Republic has the least light pollution of any country in the world. "When you fly over, it's like the paleolithic era," he said. "Almost no electric lights, just the glow of little fires."

Darkness fell as we clambered from the boat, and Sarno shook hands with four bored guards from the Armed Forces of the Central African Republic (Faca), shotguns resting across their knees. Their presence, though apparently unthreatening, had been enough to keep from the region the brutal but disorganised anti-balaka militia, the second wave of lawless fighters responsible for the country's ongoing civil war. Sarno expressed his gratitude by handing over a couple of banknotes: the first guards not to try to extract money were rewarded for their restraint. We then squeezed into another 4x4 for the final three hours of our trip: a lurch through deep puddles (it was the rainy season) and with undergrowth whipping either side of our vehicle. The headlights flickered out at every puddle, but remarkably our driver kept us gradually inching forward.

We stopped at what I later discovered was a Ba'aka village so that Sarno could buy a bundle of marijuana from a friend – all Ba'aka smoke prodigious amounts, and Sarno is a keen consumer – and eventually arrived in pitch darkness of Yandoumbé. Sarno, Samedi and Agati hauled their bags and suitcases from the boot, lit only by a couple of hand-held torches and some distant fires. But it was obvious we were now surrounded by an excited and populous welcoming committee, who swept their returning friend into his home.

I was due to be staying at a lodge around nine kilometres away, but our car's engine had apparently run out of miracles and now threatened to leave me stranded short of the finishing line. After seven or eight unsuccessful attempts to get us started again, we could gradually feel ourselves being shoved backwards out of our rut.

Eventually, the engine caught and its diesel growl was accompanied by a chorus of delighted cheers. The headlamps also came on for the first time since we had stalled, suddenly illuminating at least 30 triumphant faces crowded in front of us. We were deep among the forest people.

The forest of spirit dances

Pygmy populations have existed in Africa for tens of thousands of years. The term itself – defined in Chambers as "a member of one of the unusually short peoples of equatorial Africa" – has occasionally been blighted by pejorative, colonialist usage, but it is the only appropriate coverall used by anthropologists to describe numerous indigenous peoples. Pygmies are typically slightly less than five feet tall and are semi-nomadic hunter-gatherers, who live in or around a rainforest.

It is all but impossible to determine Ba'aka population numbers, with the most durable estimate being around 30,000. Their protein comes from the animals they can trap in the nets they weave from strips of liana bark, else spear from the trees – antelope, porcupine, monkey. Their staple starch comes from manioc (or cassava), traditionally obtained by trading the treasures of the forest with the Sangha-Sangha, the fisher-people who live by the imposing, life-giving Sangha River.

Despite prospering in this manner since the beginning of civilisation, however, the delicateness of the lifestyle has been made chillingly apparent by the encroachment of the lumber industry during the late 20th century. The international bush-meat industry regards the rainforest as a self-replenishing larder, yet the logging companies have reduced its size so dramatically in the past 50 years that it can now barely support those people most dependent upon it, let alone outsiders.

After a day recuperating from the exertions of our journey across Cameroon, I took a 40-minute ride on a motorcycle taxi from my base at Sangha Lodge, the only viable accommodation option in the area, to visit Sarno's home in Yandoumbé in daylight. I arrived to find him in conference with an ailing old widower who, Sarno explained, had recently lost the second of his two daughters to illness and was reduced to climbing trees to pick nuts to sell. He was looking for financial assistance from the world traveller, but Sarno had already parted with all of the money – approximately €600, from sales of CDs at film screenings – he had brought back from Europe, paying off debts run up by his family during his absence. At Sarno's request, I handed over 2,000 Central African Francs (about 3) to the man, who departed leaning heavily on tall splinter from a tree trunk he was using as a crutch.

Sarno's house, made of wood scavenged from the now-abandoned lumber mill in Bayanga, sits at one end of a clearing, around which are scattered eight or nine low dwellings occupied by other Ba'aka families. The village has three of four such clusters of housing (it is constantly in flux), either side of a typically uneven track. When Sarno first arrived to the Central African Republic, the community of Ba'aka who would eventually become his close friends lived closer to Bayanga, where they were frequently bothered by the Bantu.

But Sarno secured permission for a plot about three kilometres away and encouraged the founding of what is now Yandoumbé, named after the stream that runs behind the village.

After receiving a windfall from the production of the first film made about his life – 2010's OKA!, directed by Lavinia Currier – Sarno was able to make their presence more secure. Sarno himself had to move in first to encourage the other Ba'aka to leave their former home, but they gradually joined him and built new houses close to his. "The community already existed, I just changed the location," Sarno says. "I didn't really found the village. After three nights, the Ba'aka started coming because they knew it was a better place, in every way. Back then, there was forest all around, it was beautiful." Now, at close to 600 residents, Yandoumbé is probably the largest pygmy village in the region.

Sarno's first two trips to central Africa lasted three months each, the maximum permitted by the tourist visas he could obtain from the government in Bangui and by rapidly diminishing finances. He slept outside on the ground on the first night he arrived but was gradually accepted by the community as he became ever more accustomed to their ways of life. As the Ba'aka began to acknowledge he was in no hurry to leave, they helped him build a house and gradually embraced his presence. "They are very tolerant people," Sarno says.

Back in New York during an enforced break from his new life, a literary agent read a brief essay he had written about his time in the rainforest, and secured a commission for a full-length book. Sarno successfully negotiated with the publisher for an advance and then with the consulate for a longer permit to remain. He purchased a one-way ticket back to Africa. "I just felt at home," Sarno says. "The Ba'aka were happy to see me because they knew me already and they knew I liked the music. And then I fell in love with this Ba'aka girl and the idea of leaving was not something I could contemplate. That's what drew me deeper into the culture, that's how I started learning the language, and going into the forest with them and staying in forest camps for two or three months at a time. The only language I would hear would be their language."

Traditional life for the Ba'aka exists in two distinct locales. For at least half of the year they live in the village where they are in easy reach of the manioc plantations, shops and neighbours of Bayanga. But at other times, for periods of up to three months, groups from the village up sticks and roam into the forest, vanishing deep into the jungle on extended hunting expeditions, which are also filled with revelry.

Sarno grew quickly accustomed to carrying his recording equipment wherever he went. He knew immediately that he was seeking more from his recording project than merely the tourist performances that the Ba'aka could sometimes be persuaded to put on in the village. While hunting, groups of 50 or more singers combine in polyphonic chorus: several vocal strands are stacked atop one another to produce densely layered songs. While loitering in camp, they entertain themselves with harp playing and flute music. Even while bathing in rivers, they are capable of beating out rhythms on the water that magically come together to form coherent compositions.

Nothing is quite as spectacular as the ceremonies of benediction, however, where Ba'aka who are properly initiated dance and sing in masks and costumes fashioned according to ancient and complex tradition. The ceremonies can last hours on end and deep into the night, among them bojobe, during which a choir of women singers plead the spirits for their blessing ahead of a hunt; linboku, a women's ceremony to which men are not permitted; and ejengi, the biggest celebration of them all, which can last several months.

As we talked, Sarno and I ambled up to a gazebo in his garden, among trees bearing jackfruit, breadfruit and avocado, and others, in a splendidly peaceful glade. The darkened rainforest surrounds the house on three sides, and small parties of Ba'aka, typically women, wandered to and fro, clutching handfuls of mushrooms and forest garlic and baskets of manioc.

We occupied the two wooden chairs on a slightly raised platform, while a group of Ba'aka, who had accompanied my motorcycle taxi from the moment it arrived, assembled themselves around us, some sitting on the floor, others standing propped against the wooden pillars. The children tumbled up and down the slight, grassy hill and became entangled in play-fights. The wooden table, on which Sarno likes to write, rapidly became a jewellery display, with scores of necklaces and bracelets, all made by the Ba'aka from beads and dried vines and carved wood, offered for my delectation. A neighbour named Mkouti sat at Sarno's feet, resting his head against the chair, and began plucking at a geedal, a six-string bow-harp. Its sound was mesmeric, especially when accompanied by Mkouti's mumbling vocals.

"I wasn't searching for a simple life," Sarno admitted. "I was just coming here to record music. I loved the rainforest and I ended up just loving being with the Ba'aka. I was just looking for a life that I would enjoy, and I found it."

It began to rain, and the heavy drops beat a refrain on the roof and coated the tumbling, naked children in a wet shimmer. They looked as if they had been basted head to toe for the oven. After about an hour, Sarno wandered back down to the house to meet Agati, who had returned from a shopping trip to Bayanga, and I was left in the shelter in between the 15 or 20 villagers who had sat with us, mainly young men chatting among themselves. They were dressed in a raggedy assortment of sports jerseys and T-shirts bearing other slogans, above cargo shorts or jeans that were either turned up or cut off.

Mkouti, who now took Sarno's seat, continued to play his harp and was joined by another young man wearing a Nigeria football shirt and with a Turkish Airlines luggage tag clipped to his belt loop. Either Sarno or Samedi had provided the gift, which had little function beyond that of incongruous decoration. (He also had no affiliation to the Nigeria football team.) The new arrival began drumming with a stick on to the back of the chair, which in turn prompted another boy to join the band, cupping his hands to produce an echo-like clap. A bowl of roasted manioc arrived, from which a couple of the youngest children feasted, swelling further their rotund bellies. When it was empty, the bowl became another instrument: a new musician tapped against its sides with the metal spoon. Soon enough, but also somehow imperceptibly, the orchestra had swelled to six or seven, with five voices and whistles.

I first noticed something else afoot when three women arrived and crowded the harp player, clapping and singing and dancing with an elastic swivel of the hips. They plunged forward from the waist, then shimmied their way vertical again, their shoulders rolling from side to side. The new voices increased the volume and the activity grew more frenetic. I also noticed Samedi for the first time since arriving that day, among a clutch of teenagers who had previously been horsing around beside Sarno's house. The teenagers swelled the group around the summer-house and were armed with vegetation, long, leafy branches, with which they were busy beating the undergrowth that led towards Sarno's orchard of avocado trees. Pretty soon, with the teenagers now also hollering into the bushes, I made out what looked like a short, green shrub quivering of its own volition in the undergrowth.

It was somehow also edging nearer to where the teenagers were slapping the trees: a figure from the forest, made of the forest, was approaching.

The figure was comprised entirely of green – top to bottom sheathed in leaves, glistening in the rain. It was about four to five feet tall, but no human skin was visible. As it stomped into view, the music grew ever louder and the activity more frenzied. It even dared at one point to step up on to the terrace, which prompted an explosion of what appeared to be either terror or jubilation. It was whipped with branches and gradually retreated back whence it came. The forest spirit had danced.

These spirit dances – of which the performance I witnessed was extremely basic – are the subject of countless anthropological studies, and arguably no Westerner has seen as many as Sarno.

Yet despite his presence at hundreds of ceremonies over the years, Sarno keeps details of his own initiations close to his chest, leading many to assume he has never played an active role.

Anthropologists, who typically stay in the field for a year or 18 months, consider initiation to be a crucial component of their studies; cultures can only be properly understood from within, and only through initiation can one peer behind the scenes.

Sarno told me that he had, in fact, been initiated in both ejengi and bojobe, but prefers to keep it more or less secret. After the spirit danced in Yandoumbé, I handed 6,000 Central African Francs (about £9) in small notes to Sarno and asked if he could figure out a way to share it around the dancers and musicians in a commensurate way. We made a play of showing me hand over the notes so the musicians would know its source, but Sarno withheld 1,000 Francs, in what he said was a lesson to his friends that their ceaseless pleading would not always yield such immediate gains. Mkouti, the harpist, made at least three subsequent plays for the money, all of which were rebuffed, and I heard the phrase "mil Franc" in countless subsequent conversations as other Ba'aka dropped by.

The banknote's presence in Sarno's pocket had become the focus of keen attention. But soon it was gone: Sarno handed it to a carpenter he had commissioned to mend a hole in his fence with a hammer he had brought back from Germany. He had not been exaggerating about having spent all his money, and my dwindling supply of local currency was much in demand.

The notion of life in the rainforest being separate from the toils of economics is now sadly much outdated. The bartering arrangements between indigenous peoples are a thing of the distant past. During the 1990s, the lumber mill in Bayanga, operated by a Yugoslav logging company, offered employment to around 370 people, mostly Bantu, and for a short period the area was relatively prosperous. The mill was a huge and unpopular drain on precarious natural resources, and was closed before it could cause irreparable damage to what remains the world's second-largest uninterrupted rainforest.

Although the World Wildlife Fund attempts to limit hunting, and has designated areas of the park into which unauthorised visitors are not permitted, poaching has depleted the forest's stock of small mammals, part of the Ba'aka's staple diet, to near critical levels.

Sarno, like any father, needs to provide for his family. Although family groups tend to be more flexible among the Ba'aka, and children will often choose the adult with whom they most wish to live, Sarno is the "official" father of both Samedi, 16, and Yambi, 12, who are brothers and whose father was killed when they were young. Their mother, Gouma, still lives in the village and her daughter, Mamalay, whose father is still alive, is also a regular visitor to Sarno's home for food and affection. Sarno's girlfriend Agati also has a six-year-old son, Mosio, who lives in the family home. Sarno has also cared for Gouma's brother since their mother died when he was an infant. The shy child could only be lulled to sleep in Sarno's arms. That boy now has children of his own, including another Samedi, and Sarno provides whatever support he can. "I love them in a way I would love my own child," he says.

"I would give my life for any of these children, there's no question about that. They're the most important thing to me."

Much to the dismay of many of Sarno's Western friends, conversations back home about his presence in the forest often veer into deeply personal territory. Questions typically whispered from behind a hand are obsessed with his relationships with Ba'aka women. Sarno told me that he has never wanted to be the biological father of any children and that he finds the prurient interest in his sex life to be both baffling and intrusive. He has been in a hardly-extraordinary tally of three relationships over 30 years – his first pygmy love, who now lives in another village; Samedi's mother Gouma, to whom he was attached for six years; and Agati – with long, unattached spells in between.

The tapes in the suitcase

My introduction to Sarno came from an old university friend named Noel Lobley, who is now a leading ethnomusicologist and in charge of the sound collections at the Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford. In 2012, Lobley told me that he had been working on a hoard of ethnographic field recordings he had unearthed in a museum store cupboard and tipped me off that the recorder of what he described as some of the most sophisticated music in the world was still alive and living in the rainforest. Lobley, who is now a close friend of Sarno's, is also mystified by the interest in anything about him beyond his life's work. "To me, it's all about the music," Lobley says.

The Pitt Rivers Museum in Oxford is one of the city's most treasured institutions. Founded in 1884 to house the private collection of the pioneering archaeologist and ethnologist Augustus Pitt Rivers, its rows of wood-framed glass cabinets now contain some 500,000 curios from all corners of the globe. There are tribal masks, costumes, musical instruments, ceramics and weaponry, as well as a notorious collection of shrunken human heads from Ecuador and Peru, which are a principal attraction but the bane of the museum staff's lives.

Louis Sarno's influence at the Pitt Rivers is, for the most part, out of the public's view. Cassette tapes don't offer much to look at. But Dr Lobley, who is in charge of the museum's sound archives, believes the aural document from the Central African Republic and Congo is among the most valuable items the museum holds. "That's the flagship [sound] collection," Lobley says. "It's the one that draws attention to everything else."

In the mid-1980s, Sarno approached Oxford university for funding for his then-embryonic project among the pygmy musicians of the Congo Basin and struck up a friendly relationship with Dr Hélène La Rue, Lobley's predecessor. La Rue was a keen supporter of trailblazing talents and recognised in Sarno the potential for a direct conduit to some of the world's most sought-after musicianship. The funds were secured and La Rue offered the university as a safe repository for what became a rapidly expanding collection.

Lobley insists that Sarno belongs in the same category as the great collectors Alan Lomax and Hugh Tracey, the field recorders who respectively mapped the sonic landscapes of the American south and much of sub-Saharan Africa, through much of the 20th century. Sarno's methods were slightly less formal: he is the only one of the three with no institutional backing nor any realistic expectation that his work might be considered to be of academic merit.

Sarno himself says: "It sort of mounted up very slowly over the years. It kind of amazes me to look at it now that there's so much, so many recordings. It is kind of a lifetime's work, so I guess it's not that surprising. But I never set out to do this, that wasn't my goal to make some kind of huge collection."

Lobley and Sarno gradually began to communicate with one another via email and eventually Lobley secured funding for Sarno to spend a month in Oxford in spring 2012, where the pair set about processing the trove of tapes. They expanded the perfunctory notes Sarno had made at the time of recordings and also analysed photographs to identify musicians and singers. During the latter part of his visit, a new cache of tapes arrived: some 400 hours of recordings from an expedition to northern Congo, which had been stashed beneath a bed in the spare room of Sarno's mother's house in New Jersey. "They're an important piece of the jigsaw," Lobley says.

Even for the uninitiated, listening to some of Sarno's recordings is an exhilarating, transportive experience. For Ba'aka, music is the lifeblood of the community and central to it; some studies have suggested that the music's balance between rigour and freedom "reflects perfectly the social organisation of the pygmies … perhaps not by chance." Even Unesco has recognised the significance of Ba'aka music and in 2008 inscribed the polyphonic singing of the pygmies of Central Africa on its "Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity". In the pop sphere, Herbie Hancock and Madonna are among those either to sample or attest influence from pygmy music, while Belgian artist Zap Mama "mixes African vocal techniques with European polyphony" in successful commercial releases.

Sarno has amassed recordings of startling authenticity. As any journalist, anthropologist, film-maker or sound recorder will know, the presence of a third party, and in particular his or her Dictaphone, notebook, camera or microphone, will prompt changes in a subject's behaviour or output, even perhaps subconsciously. It is particularly marked when recording musicians, who may abandon their freewheeling spontaneity in favour of more formal, practised and safer ground. But Sarno's immersion with the Ba'aka afforded him the great privilege of being ignored entirely. At times, particularly during hunts in the forest, where singers can be stretched across many miles, his microphones were probably unseen by the people he was recording. It is a position that to some anthropologists transgresses an ethical boundary, but which has given Sarno's collection extraordinary value.

The vast majority of Sarno's recordings are now digitised and catalogued, ensuring their continued availability to students and researchers, as well as the general public, who can find large sections of the music on the museum's website. Lobley has used the recordings as the soundtrack to events at the museum and says he is in the early stages of planning another collaboration with the Oxford Contemporary Music Orchestra this year, in which high-profile artists will be offered access to the collection and invited to interpret it as they wish.

"I love the Ba'aka and I don't want them to just disappear without a trace," Sarno says. "With all this music, if it's in the sound cloud and it's on the internet, it becomes accessible. It will give them an input into the future and that makes me happy. I'm really glad about that."

Wrestling the hunters

Through his recent work at the Pitt Rivers Museum – the essential admin concomitant with his recording in the field – Louis Sarno has secured the Ba'aka of his village a place in musical history. But having watched close friends and children die of preventable illness, and seen the habitat in which the Ba'aka have thrived for centuries eroded over recent years, Sarno's more pressing concerns centre on the precarious immediate health and livelihood of his friends and family.

In 2009, a malaria epidemic swept through the Ba'aka communities close to Bayanga, claiming the lives of dozens of children in less than two months. The Ba'aka have no natural immunity to the various mutations of the disease and it is the single biggest killer of pygmies across Africa. Sarno improved water supplies and latrine facilities when he helped to remodel Yandoumbé, combating water-based disease, but malaria control (and defence against tuberculosis, which also kills generations of Ba'aka) demands medicine most likely manufactured in the West. Sarno now has a suitcase of pharmaceuticals in his house, from which he dispenses life-saving drugs. As he has gradually schooled the Ba'aka in the importance of preventative medicine, there is a constant stream of visitors at his door.

"Louis Sarno plays an important role in the fight against malaria," Julia Samuel, the operational director of the Drive Against Malaria (DAM) Foundation, tells me in an email. (Samuel and her team are working in Cameroon to try to stop Ebola entering the county.)

Samuel says the foundation first encountered Sarno after the 2009 epidemic and she forwards to me an official document in which Sarno is named as the figure around which the programme in the Central African Republic revolves. The DAM document offers a chilling assessment of how dangerous malaria is in the region, and how vital Sarno's work in Yandoumbé is considered. "If there is no swift action, there is a good chance that within a year malaria will again cause mass deaths among the children of Yandoumbé, and at worst will destroy the whole population." At time of writing, the Ebola epidemic that began in the summer of 2014 has not made its way to the Central African Republic, but the mere mention of the disease's name terrifies the Ba'aka.

Sarno rarely has disposable income, and does not receive payment for his unofficial role as village pharmacist. Instead, throughout his time living in Yandoumbé, he has found various inconsistent means of scratching together money, including as a fixer for the succession of film crews that have recorded footage in the rainforest. Over the same period of time, some Ba'aka have been able to find work with the WWF, for whom their jungle skills are enormously valuable. On the Dzanga Sangha Reserve, for example, their tracking skills are greatly valued by the WWF's unique gorilla habituation programme.

Rod Cassidy, an ornithologist and the proprietor of Sangha Lodge near Bayanga, has also worked with Sarno in offering tourists the opportunity to sample time in the forest with the Ba'aka.

"I believe, in my heart, that if people had seen the value of the Ba'aka culture in the 1980s or the 1970s, they could have turned this place into an exclusive Ba'aka hunting ground, and allowed tourists in here, and it would have been the biggest wildlife coup in the world," Cassidy says. "But instead, they formed national parks, ostracised the Ba'aka. The logging companies have come in, trashed their forest for them, and it's a mess."

Yandoumbé and Bayanga lie inside the Dzanga Sangha Reserve, a 4,000km2 area of the Central African Republic, which in turn is a part of the Sangha River Tri-national Protected Area, which also spreads into Cameroon and Congo-Brazzaville. Two sections, the Dzanga and Ndoki sectors, (covering 495 km2 and 725 km2 respectively) have been designated the Dzanga Ndoki National Park, in which all hunting, including that practised only with nets by its indigenous people, is prohibited. The Ba'aka have as a result been forced to take their chances in a region between the national parks, known as the "community hunting zone". Even the name infuriates Sarno. He says it practically advertises the region to those hunting with guns and wire snares for profit rather than with the traditional methods employed by the Ba'aka, who hunt to stay alive.

"For their way of life in the forest to continue, the Ba'aka need an abundance of wildlife because their hunting methods are very inefficient," Sarno told the audience during a Q&A after the film premiere in Berlin. "If there's not enough wildlife, they can go hunting all day and not catch anything. The poaching with shotguns is just decimating the small mammals, the duiker populations have crashed, and it's the same with monkeys. These are animals that the Ba'aka hunt."

Sarno tells me how frustrations have often spilled over. On one evening at the beginning of the year, after a day watching Bantu hunters traipse past his house with backpacks filled with forest booty, Sarno says he was approached by a 16-year-old pygmy boy, who was in tears. The boy said that gendarmes, supposedly ambushing poachers, had beaten him and confiscated his spear, machete and the single porcupine he had caught.

"I got really angry," Sarno says. "So I went down and I didn't realise because I didn't look behind me but a whole bunch of Ba'aka were following me with sticks. And when we got there, I guess they saw this big group armed with sticks and they sort of got worried. And the gendarme guy pulled out his pistol."

Sarno describes a scene of near riot, as he wrestled with the pistol and the Ba'aka came to his defence. After the situation eventually calmed down without serious injury, the authorities threatened to arrest and deport Sarno, drawing the WWF into the fracas. "The authorities eventually supported me," says Sarno, "but then the World Wildlife came by and said, 'Oh, it's very bad that you did this. If there's a problem with the project, you should bring it up, come and talk to us about it'. I said, 'Well, I've been telling you for a few years now about this problem and it keeps happening.'"

Johannes Kirchgatter, the Africa Projects leader for the WWF, acknowledges that the situation in Dzanga Sangha is far from ideal. He also concedes almost all of Sarno's points concerning over-hunting and lack of adequate policing in the community hunting zone. However, Kirchgatter, who speaks very highly of Sarno's value as a bridge between the Ba'aka and the WWF, says the organisation can only do what it can in the extreme circumstances presented in the area, particularly since the 2013 coup d'état.

"The problem is that the WWF is almost the only institution working there," he says. "All problems that occur are blamed on us. Whatever happens is blamed on WWF."

The Ba'aka often find themselves without adequate representation in an endless series of high-level talks between the CAR government (such as it is), the WWF and other NGOs, as well as logging companies with their eye on the tropical hardwood. There have been a number of reports published through the years concerning how best to carve up the forest with only the most meagre lip service paid to the interests of the Ba'aka. Although one of Sarno's friends in London jokingly refers to him as the "Ba'aka foreign minister", he is a reluctant out-and-out spokesperson. "If porcupine hunters are being harassed by the guards, I'll put a stop to that by having a small riot," Sarno says, "[but] I don't go out advocating for them."

Perhaps the most exciting proposal for securing the Ba'aka's voice on all levels of discussion is a project by Oxford-based organisation Insight Share, with which Sarno has recently been in contact. Insight Share was founded 15 years ago by the brothers Nick and Chris Lunch and brings video skills to under-represented communities, who are then encouraged to produce short documentary films from a unique insider's viewpoint.

"Participatory video", as the process is known, has been successful among indigenous communities in Ethiopia, Peru, Panama, and the Philippines, among others, and also recently brought a wave of awareness and funding to a Baka community in eastern Cameroon. The videos are markedly more authentic for having been produced by trusted community members and provide perhaps the only real representation of the indigenous people's lifestyle, free from either sentimentality or the editing out of inconvenient truths. Insight Share provides a long-term commitment, including training and equipment, and their continued success hinges on the presence of a trusted facilitator – someone like Louis Sarno.

Sarno is confident that the Ba'aka of his village would be hugely enthusiastic for the project and is hopeful that Samedi, who has developed an interest in film through his starring role in the recent German documentary, may be inspired to get involved. Nick Lunch is already working with Richard Gayer, one of Sarno's close friends based in London, to raise funds and assess logistics to bring participatory video to Yandoumbé some time in 2015.

"Louis' role is absolutely central, as sort of a gatekeeper, in this project," Lunch says. "When we raise money for this project, we must allocate a salary for Louis."

Spraying bullets

In early 2013, the peace in this small corner of the Central African Republic's far south west was brutally shattered by news emanating from the capital. There were graphic tales of the kind of violence to which the country has never previously borne witness. "I was hearing BBC reports and through the Mauritanian shopkeeper, who had his contacts in Bangui, about the approach of the Seleka," Louis Sarno says.

Towards the end of 2012, a rebel army bearing a name that means "alliance" or "coalition" in the country's official language Sango had fought its way to power in some northern and central regions of the Central African Republic. The president of the past decade, François Bozizé, initially tried to stem the rising wave of disruption and dissatisfaction by signing a peace accord with Seleka leaders and offering a number of compromises. But in March 2013, claiming exasperation at broken promises, Seleka militia marched all but unopposed into Bangui and toppled the president.

Bozizé, who had seized control in a similar coup d'état 10 years previously, did not hang around to fight his corner. The buzzing sound heard near Bayanga soon after, coming from the direction of the Sangha River, turned out to be the engine of a boat motoring the president to exile.

Locals joke that the Central African Republic has survived coups d'état approximately once a decade since it earned independence from France in 1960. But this time, the change of government in Bangui precipitated two years (and counting) of savagery that has terrifying echoes of past conflicts in Rwanda and Darfur. The Seleka, a mostly Muslim coalition, rampaged through the country for about a year, with little more than token intervention from France, wary of previous failed operations in their former colonies in Africa. But then, citing defence of the country's religious identity, loose rabbles of mainly Christian militia sprang up across the Central African Republic, assembling under the title "anti-balaka".

The anti-balaka further terrorised the country and slaughtered Muslims, often showcasing their butchery in front of the relatively few international journalists covering events. Almost all Muslims have now either been forced to flee the Central African Republic or have been murdered standing their ground – and still the violence continues. According to most recent reports, "thousands" are dead and 430,000 people have been forced to flee their homes.

News of Bozizé's routing reached Yandoumbé quickly in March 2013. Word swiftly followed that the Seleka were on their way and workers from the WWF and other NGOs had been persuaded to flee. Sarno initially chose not to go, but the year that followed would become the most turbulent he had endured since first arriving in Africa.

The Ba'aka, known to be the poorest people in the country, were not an immediate target of the Seleka, whose beatings seemed primarily designed to extract money. Besides, the Ba'aka's survival skills allowed them to vanish into the forest, a natural refuge from the Seleka forces, which comprised mainly ill-equipped, desert-dwelling fighters from the north. Sarno retreated to the forest with four of five Ba'aka families for the first three weeks after the coup d'état, hoping to weather the storm beneath the canopy.

But word soon came from Shamek, a Muslim, still manning his shop in Bayanga, that a second group of Seleka was on the way. They were nastier than the first, and Sarno was one of their principal targets.

There were rumours, which had apparently now reached the Seleka, that Sarno had prised from the Ba'aka the location of the rainforest source of "red mercury", a mythical commodity, but thought to be more valuable than diamonds. Sarno says: "The local Africans always wondered, and some of them had said to me, 'We know why all the other white people are here, but we haven't figured out why you're here … There's something you're not telling us. We haven't figured it out yet, but I think it's because of this mercury.'"

The Seleka threatened to take Ba'aka hostage should Sarno not emerge with his secrets from the forest, finally leaving him with no choice but to flee first to Congo-Brazzaville, with his family, and then to the United States, by himself.

"It was the worst moment of my life in a lot of ways," Sarno says of the time he bade farewell to Agati and their children. "They were going to head into the forest, so they would be all right. But it was horrible just leaving them like that."

What he initially expected to be a three-week trip to America stretched into three months of misery. The Seleka rampaged through Yandoumbé and Bayanga and every phone call with Shamek described new horrors.

Seleka climbed a viewing platform in the national park and sprayed bullets through the families of bathing elephants, killing 26 animals and hacking off their tusks. They also ransacked Sarno's house, tearing apart his notebooks containing work from 30 years, destroying recordings, stealing medicines and crunching beneath their boots the last authentic example of the mbyo flute known in the world. It had been bequeathed to Sarno by its last maestro, who had since died.

Shamek managed to use his financial muscle to halt further slaughter of elephants, convincing the Seleka general to focus his efforts on warding off other poachers swarming to the area. The elephant massacre also belatedly brought international attention to the plight of Dzanga Sangha and Sarno got wind that a former Israeli commando named Nir Kalron, who had more recently turned his attention to conservation in the world's most threatened areas, was leading a party back to the region to ensure the protection of the elephant habitats.

Meeting up with the conservationists in Cameroon, Sarno travelled with them back to Bayanga and, emboldened, realised it was time to negotiate with the Seleka leaders. "I knew where the base was, so I went," Sarno says. "I walked up and I said, 'I want to see the colonel'."

Speaking through an interpreter to the Chadian Seleka colonel, Sarno demanded the Ba'aka be left alone. They had nothing to offer, he said. The colonel seemed willing to co-operate and Sarno gave him a Casio watch for his understanding. (The colonel later said: "I will die with this watch on my arm.") The largesse bought immunity from hassles by senior figures in the Seleka but instructions did not filter to the underlings. Soon, after many more petty invasions to Yandoumbé, Sarno and the Ba'aka upped sticks again and fled into the forest, where they stayed for another three months.

Even after the Seleka were finally beaten into retreat, however, and their own president deposed in Bangui, any return to Yandoumbé was short-lived. The anti-balaka arrived three days later. Shamek, whose presence in Bayanga had been invaluable during the Seleka's occupation, was forced to flee across the border. His store was ransacked by looters, and enormous credit accounts (including one extended to Sarno) remain unpaid. Other Muslims had little option but to follow him and stay in refugee camps in Congo-Brazzaville and Cameroon. Many were forced to part with huge cattle herds, their entire livelihood sold for a pittance.

Sarno and Cassidy both stared down anti-balaka brigands, sensing that the bravado of the young mercenaries would be unable to withstand the gumption of their seniority. There was no chain of command among the lawless groups, so negotiation proved impossible, but both adopted the kind of strategies best employed to undermine a playground bully.

"If you act scared in front of them, they get worse," Sarno says. "But if you stand up to them, they back off. They had a real bully, thug mentality, the anti-balaka. They knew that I'd come back when the Seleka were there, so there was something about me they weren't quite sure about. So I was just standing up to them. I wasn't afraid to scold them … They're not afraid to kill people, because they have killed people already and are used to it. But for me, it was just a bluff."

Eventually, Sarno and Cassidy, among others, managed to persuade what was left of the municipal authorities to arrange a small group of fighters from the Faca to come to the area. As expected, the bullies of the anti-balaka disappeared at the first sign of a force with bigger guns. The Faca remain in the region and a delicate peace holds.

It is difficult to quantify now what was lost during the raid on Sarno's home. His journals and flute were irreplaceable, but even more so, any notion of an Edenic idyll was permanently shattered.

While exiled in the United States, Sarno wrote a fresh account of the Seleka occupation of Yandoumbé, a 19,000-word essay named Flight (From Paradise). It is astonishingly good: an impassioned telling of what remains a globally under-reported crisis, from Sarno's unique viewpoint from deep within the country's overlooked indigenous community. It is deeply personal, but tells a story of broad relevance. Sarno's Ba'aka friends are given the rounded characterisation often absent from anthropological and journalistic studies, while the narrator, who describes himself as "a bag of fragile bones", offers bitter commentary.

"I'm still a refugee in the country of my birth," Sarno writes. "Five, six times I've had to delay my return to Africa, as I watch my beautiful adopted country Centrafrique being pulverised, driven into the dirt. People murdered; houses, offices and hospitals looted; whole towns pillaged; kidnappings for ransom; brutal mass rapes, as if the militias are intent on raping every woman and girl in Centrafrique."

He continues: "I'll let you in on a secret. When those Sudanese poachers came to Dzanga bai and slaughtered 26 elephants with automatic weapons and then chopped off their faces to free the tusks, I was glad.

I really was! Because I knew that now, finally, there would be a vigorous international response."

'Maybe I've damaged them'

Today, Sarno has reason for cautious optimism. The film-makers behind Song From the Forest have put in place a mechanism by which audience members are encouraged to donate to a fund for the Ba'aka. Proceeds from the soundtrack CD, comprising Sarno's recordings, also go directly to him. He used some of these funds to build a new house, which cost the equivalent of €2,500. Ba'aka builders helped him with construction.

Sarno is travelling to New York this month and has also agreed to a re-release of his only published memoir. He says he has not softened in his opinion of its qualities, but needs the money a boost in sales will bring.

Moreover, Sarno is in poor health and now makes the most of trips out of Africa to receive treatment for a number of ailments. His medical record reads like an encyclopaedia of exotic maladies – leprosy, loa loa, typhus, malaria and hepatitis B and D – but their combined effects, particularly on his liver, have left him requiring regular surgery that is not available anywhere near to his home.

Sarno told me that he accepts the health risks of the life he has chosen to lead – "Everyone else gets cancer from car exhaust in the city; each place you live has its own risks" – but also knows that he will die should any emergency take place while he is in Yandoumbé. He will combine the trip to the United States with another stay in hospital for some preventative surgery.

"I don't feel that I have very long to live, so my time is valuable," Sarno tells me during our journey across Cameroon.

For all the health-scares, coups d'état and warnings of the perils of jungle life, some time this year, Sarno will celebrate his 30th anniversary of permanent residency in the forest with his family.

Yet, in his more reflective moments, he says he questions whether his presence among the Ba'aka has been of any lasting value. He even wonders if his time in the forest may have had more negative effects than good on the people who have welcomed him to share their home.

"My life has been enriched," Sarno says, "[but] for them has it ultimately been a good thing? I mean, it's been a good thing for certain individuals. I've helped people out. My interventions have helped save people's lives and stuff. But has it been good for the whole community in general? I don't know."

Closest to home, Sarno's specific concerns centre on Samedi, his oldest son, who has been afforded the kind of opportunities almost no other boys in his position could expect. Samedi does not appear to have been overwhelmed by what he has seen of the Western world – he rarely comments to his father about his travels and has never expressed any desire to leave Yandoumbé for good – but Sarno says he has also not pursued the development of hunting skills as keenly as other boys his age. Sarno worries that Samedi may develop unrealistic expectations, perhaps one day to live in the United States, which will leave him unfulfilled by his life in Africa.

The same fears run through Sarno's preoccupations about his Ba'aka friends in a wider sense. "Maybe I've damaged them in some way, that they're unsatisfied with the traditional way of life," he says.

Sarno has typically not been able to resist disrupting what he considers to be an imbalance between the various community groups in the area. He has, for instance, always demanded Ba'aka be paid for their work and had stood up for them in conflicts against the Bantu of Bayanga, going against the long-established status quo. He told me that in some ways, however, Ba'aka seem more comfortable in the victims' role, when they are not burdened by the demands of economics and village life. They are much more vibrant and, specifically, musical when they are out in the forest, yet spend increasing amounts of time idling in Yandoumbé.

"I've been a big traditionalist but I don't believe they should be owned by other people, things like that," Sarno says.

"I believe they should be considered fully human. But, you know, I like to see them retain their forest skills and pride in their music and all this kind of stuff. Somehow they still have their music, but it's not as strong as it used to be. Is it my fault? I don't know."

During his early years in the rainforest, Sarno says he drew some criticism from anthropologists for his lack of academic qualifications and for methods of integration that do not conform with those expected in the discipline. I struggled to find concrete evidence of these criticisms, but Sarno still considers himself to be a pariah among academics, particularly in the United States. However, he also insists repeatedly that he is neither an anthropologist nor a musicologist, titles that suggest formal training, and is frequently bewildered by the interest shown in him, academic or otherwise.

He has said he feels that his life in the Central African Republic is no more remarkable than anyone transferring East Coast for West in the United States, or trading one European capital for another.

Many of Sarno's Western friends consider his only real failing to be his apparent unwillingness to share his vast knowledge; his lack of interest in publishing what he has learnt from his time in the forest. Despite a lack of formal qualifications, he has done what amounts to the fieldwork of about 10 anthropologists, and has insights into the lives of the pygmies of Yandoumbé that no one else has ever collated.

Lobley has floated the idea of Sarno travelling to Oxford more regularly, in some kind of visiting professor's role, but the logistics of admission to academic institutions are notoriously difficult to arrange, particularly with Sarno himself often unwilling to jump through countless administrative hoops. Others have talked about securing Sarno an honorary degree ("They bloody well should give him one," says John Dunbar, one of Sarno's London friends) but arguably much of the unique value of Sarno's work has depended on his freedom from institutional commitments.

Despite his bad experience with his first memoir, Sarno has actually continued writing over the past 30 years. He has completed at least two other book-length memoirs while living in Yandoumbé, neither of which have been distributed beyond his circle of friends.

Although his first unpublished memoir, Last Thoughts Before Vanishing From the Face of the Earth, was the source for OKA!, the manuscript reportedly bears little resemblance to the screen version. Sarno says the other book, detailing a long excursion he took with two Ba'aka friends into northern Congo, did not impress his agent in the US. Both are unpublished, and Sarno says he is not sure where the manuscripts are. (I managed to find one in Dunbar's house in London.)

Sarno confesses to having adopted some of the Ba'aka's habits, in particular a live-for-the-moment attitude; they do not concern themselves with either the past or the future and Sarno speaks fondly of the outlook.

"You're more alive," he says, describing the Ba'aka philosophy on life. "You're living in the present; the past doesn't exist any more. And it's good, otherwise you get hung up about problems in the past and grudges. The past is finished. You've got to make the present as pleasant as possible. And the future, well it hasn't happened yet, so why should you worry about it?"

"I think it's been a positive thing in my life. Sometimes it makes it hard to live in the modern world, not thinking about the future. The modern world, people are hardly living in the present at all, they're always worrying about the future."

In a recurring fantasy, Sarno says that he wants one day to go even further into the forest, and never come back. He knows of a small clearing, free of fresh growth, in which he sees himself residing permanently.

"If I had really good money and when I ran out of darjeeling tea I could get some shipped out somehow and brought out, I could be very tempted to just stay in the forest, especially if they could make me some kind of chair that I could sit in and a table where I could write," Sarno says.

"I would be happy to stay out in the forest. It's beautiful."