Dire indeed will be the day when the Anderson Valley Advertiser of Boonville, California, becomes "America's Last Newspaper," as its masthead proudly but not yet accurately proclaims. For that would relegate the final vestige of our vaunted free press to nothing more than an open mic for Mendocino County paranoids, weedheads, malcontents, crooks, cranks, off-the-gridders, rednecks, wonks, wankers, pedants, loons, autodidacts, Luddites and Silicon Valley castaways. When that day comes, sorely will we miss USA Today infographics on the sexual proclivities of Minnesotans, and the 37th New York Times article proclaiming Provo the next Brooklyn.

But the AVA is not America's last newspaper, at least not yet. The Palookaville Daily Democrat is said to be thriving, for one. But the AVA may well be one of the very last genuinely American newspapers, which is why the most trenchant of the many decorations on its office's wood-slat walls, aside from a post-massacre Charlie Hebdo cover, is a bumper sticker above the door that says, "AVA Nation: Boonville to Brattleboro."

Boonville is a good two hours north of San Francisco, while Brattleboro, Vermont, is two hours north and west of Boston. There are no AVA subscribers in Brattleboro today. Regardless, the bumper sticker makes a valid point, for the AVA has long attracted an audience far beyond the verdant hills of Northern California.

"The hometown paper for people without a hometown," is how editor Bruce Anderson, 75, explains the weirdly broad appeal of the newspaper he has owned since the days when the best way to share an article with your aunt in Duluth was to clip it from the paper and mail it to her (i.e., 1984). It is a paper for those who remember America pre-Wal-Mart, who yearn for a Main Street not yet colonized by Little Caesars and Dairy Queens. For those who, as Anderson laments, live in "franchise hellholes." In other words, pretty much all of us.

"People still want to read about the area they live in," Anderson says of his newspaper, deemed in 2004 "one of the country's most idiosyncratic and contentious weeklies" by a scrappy little broadsheet called The New York Times. "The big newspapers don't do that," says the bearded editor, crisply dressed and irrepressibly loquacious, ever the irascible uncle who slipped you your first Bud Light at the family barbecue way back when. "And they have the resources."

Nor do the big papers, for that matter, publish the likes of John Kendall of Rancho Navarro, who wondered in a letter last month to the AVA about a "strange light moving across the sky." Elsewhere, this would be disregarded as paranoia. In Boonville, it's serious stuff, seriously taken. In early March, Tim Glidewell of Boonville wrote that "[t]hese strange lights in the sky keep happening." He discounted the possibility of a drone, then tried to rally his fellow citizens to seek out the truth: "What's going on here, people?"

Perhaps, then, the AVA will be the last newspaper in America because it will be the only one sufficiently prepared for the inevitable extraterrestrial conquest.

"When I'd fled north for Mendocino, the Vietnam War went on and on, and amphetamine, heroin, the criminals who sold it, and random homicidal maniacs had taken over the city streets," Anderson wrote of leaving San Francisco in the early 1970s in his memoir, The Mendocino Papers. A product of Marin County who pitched a 13-inning shutout in high school ("the highlight of my life"), Anderson served in the Marine Corps and later went to the California Polytechnic State University in San Luis Obispo and San Francisco State. After college, he joined the Peace Corps, which sent him to Borneo. There he met Ling Mowe, with whom he recently celebrated a 50th wedding anniversary.

His explanation for their marital bliss: "She doesn't speak English."

Back home, Anderson dabbled in progressive politics, serving as a founding delegate of the Peace and Freedom Party. In 1969, he and his wife became foster parents to two "mega-troubled" teenagers. The brood moved to the Anderson Valley two years later "on the naive assumption that juvenile delinquents would be less delinquent under the redwoods," as he told the AVA in an interview last year. Leasing a ranch, the Andersons would have as many as 10 children, all with criminal records, under their care.

Once a logging and ranching town, Boonville had become primarily famous for Boontling, a jargon developed in the late 19th century. A still-authoritative book on Boontling by Charles C. Adams was published in 1971, and a local named Bobby "Chipmunk" Glover, happy to harb a slip of the Ling for outsiders' amusement, appeared on The Tonight Show With Johnny Carson. But a quirky vocabulary can't quite power a regional economy. It would be decades before Bay Area tech wealth started wafting over these ample hills.

Despite the high local incidence of stoners and hippies, Anderson quickly found himself at odds with "local adversaries in the school system and the courts." The country, in other words, was proving no mellower than the city. But at least its denizens were easier to shout down. Borrowing $20,000, Anderson bought the AVA from "a woman desperate to get out of here," as he recalled last year.

Founded in 1952, the Anderson Valley Advertiser had not exactly been gunning for the Pulitzer Prize in its 30 years of existence. It had been started by Eugene Jamison, a Round Valley American Indian, as an advertising brochure that began reporting the news the following year. In fact, the newspaper's first breaking news item was that Boonville could print a newspaper, with the first edition of the first volume bearing the headline: "THIS PAPER IS PRINTED IN BOONVILLE." For a single thrilling moment, community journalism and media self-reference united in the backwoods of Mendocino.

Anderson had bigger ambitions. He sought to make the AVA "interesting and lively enough to attract readers from outside the area." Among those who helped in that regard was Alexander Cockburn, the prominent liberal journalist and Christopher Hitchens sparring partner. As would often be the case in the future, Anderson simply wrote to Cockburn in New York and asked him to contribute. Cockburn agreed and, eventually, moved to the Anderson Valley. He passed away in 2012, but in his posthumous book of writings on life in America, A Colossal Wreck, he makes clear his fondness for the AVA, which he wrote "does everything a newspaper should do." Cockburn's colleagues from the progressive magazine CounterPunch continue to appear in the AVA.

Robert Mailer Anderson, Bruce's nephew, became an unofficial AVA fiction editor in the 1990s. Among the talents he attracted to the newspaper are Daniel Handler (better known as Lemony Snicket), who published a short story there, and the renowned illustrator Sandow Birk, who has spent about a decade on an American version of the Koran. Anderson, who has written a well-received picaresque novel called Boonville, also published well-regarded Bay Area voices like Floyd Salas and Michelle Tea, making the AVA more than just a rickety soapbox for grumpy white geezers.

But in 2004, Anderson sold the AVA for $20,000 to David Severn, author of the oenocentric "Vine Watch" column. Anderson told the Times that the Anderson Valley had "become a wine region, with total strangers dominating the political life. I began daydreaming about murdering certain people. I said, You know, this place isn't really healthy for me anymore." The Andersons moved to Eugene, Oregon, where Bruce started a paper similar to the one he'd just left. But the AVA Oregon proved a bust, and three years later, Anderson returned to Mendoland. He bought back the AVA for $20,000. That same year, Twitter was valued at $35 million.

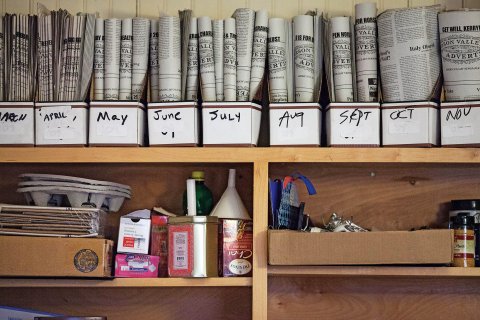

Today, the AVA is really a two-man operation with accoutrements, with sleepy-eyed but sharp-minded Mark Scaramella, known as The Major, playing the Sancho Panza role. Ling keeps the books, though she doesn't read the paper, her husband says. Much of the rest of the AVA is put together by contributors who are paid $25 per article. That's not enough to retire on a Russian River vineyard, but Anderson reminds his writers that it is what Mark Twain once earned, per week, for plying the journalistic trade in San Francisco.

Given the free and odd spirits who pervade the Anderson Valley, the result is Our Town on bad Mendo meth, a Norman Rockwell scene painted in the midst of a weed-wine binge and given a makeover by Hunter S. Thompson. Behold a typical issue from 2013. Above the fold is a dispatch from court reporter Bruce McEwen, titled "Tweakers & The Women Who Love Them." In the "Valley People" rundown, a notice laments that the "smugly oppressive dominance" of the Anderson Valley School Board by certain "palsy-walsy" potentates has made it "a kind of self-perpetuating monument to rural nepotism." This, mind you, in a news report, not an editorial.

"Things don't always make sense here in the Valley," explains occasional AVA contributor Debra Keipp, who was working on an article about the crude barroom antics of a local official when I met her. The article, she said, was slightly too vituperative for Anderson, which is no small feat. ("Deb's hate is pure," Anderson told me when I asked him about the article, "but that one was a little too pure even for me.") Usually, he craves invective, hyperbole and outrage. This is not the anodyne community rag for old ladies who want to clip coupons and read about lost felines. It is, instead, a weirdly edgy and sophisticated operation for old ladies with a backyard ganja grow, a degree in political science from Berkeley and a predilection for Thomas Pynchon.

And old ladies who might be Thomas Pynchon. In the 1980s, rumor took hold that the famously media-averse Gravity's Rainbow author was writing letters to the AVA as a local Jewish spinster named Wanda Tinasky. The rumor was inspired in good part by Anderson, who loves media attention as much as Pynchon detests it. The letters were verbose and arcane in much the manner of Pynchon's fiction. It helped Anderson's claim that Pynchon was known to have been living in Mendo while researching his 1990 novel, Vineland, which some believe is set in Boonville. Anderson's reading of that novel made him think Pynchon was Tinasky. "It has been suggested," he once wrote, "that Pynchon dashed off the Tinasky letters as a warm-up exercise for a day's work on Vineland."

Some years later, the author Donald Wayne Foster, who had concluded that political journalist Joe Klein was behind the Clintonian novel Primary Colors, persuasively surmised that the Tinasky letters were written by Tom Hawkins, a Beat poet who killed his wife and then himself in 1988, right after Tinasky had published her last letter to the AVA. It is nevertheless telling that the Tinasky legend persisted for so long. When weirdos publish their weird missives in The Des Moines Register, nobody suspects Pynchon. But it somehow made sense that he would contribute to a newspaper that, like his fiction, treats all authority with paranoia, mocks yuppie pretensions, questions the motivations of those with power and never misses the chance to make a puerile joke.

Above all, Anderson values the AVA as a forum for the everyman (though, of course, no one gets as much time onstage as the man who owns the presses). "I think some of the letters we get from prisoners are great," he says. "I'd much rather hear from Joe Schmo than I would, say, George Will."

But no voice is quite as welcome as Anderson's own, along with those that echo his sensibilities. "Freedom of the press," the great New Yorker scribe A.J. Liebling once quipped, "is limited to those who own one." Anderson can, accordingly, say whatever he wants about the local politician, the finance minister of Greece, the wine industry, the oil industry or the strange old dude at the Buckhorn who drinks only Shirley Temples. And say it he does, week in and week out. Every enemy, real or perceived, is obliterated with a missile strike. His foes' only recompense is that they are invited to respond in the AVA, sometimes in the very issue where they've been savaged.

Here is columnist Malcolm Macdonald on county official Dan Hamburg: "I'd sooner vote for a wild hog rooting up my trees than you again."

The writer Todd Walton on American exceptionalism: "a cancerous blood clot in the main artery of what might otherwise be an effective, functional, egalitarian global community."

Anderson on Alice Walker, who supposedly wrote The Color Purple "in a shack not far from downtown Boonville": "Her more recent writings," he thundered in 2004, were "the prose equivalent of chipmunk paintings and Hallmark narratives."

You get the point. In the eyes of some, the AVA's relentless pugilism makes Anderson a bully disguised as an underdog, a supposed freedom-of-the-press champion who happens to own the only press in Boonville. "He attacks a lot of my friends," says Jimmy Humble, a disc jockey with KZYX, a favorite Anderson piñata. "It's not fair. He's got this paper." As we chatted at the Mosswood Market, Humble complained about the time Anderson called him "Jimmy Bumble" in print. Humble responded with a letter the following week informing "Mr. Panderson" that his name had been misspelled, signing it "Dimmy Bumble."

Others have been less gracious: In a lengthy essay titled "Liar Unlimited: The lurid history of Bruce Anderson and the Anderson Valley Advertiser," Mike Sweeney makes Anderson look about as likable as a Der Stürmer scribe. The wellspring of the bad blood between Sweeney and Anderson is too complicated to explain, but this being Northern California, it involves a radical environmentalist and a car bomb in Oakland. (If you really want to know, plug "Judi Bari" into Google and enjoy the trip.)

The origins of the feud notwithstanding, Sweeney points out some of the more flagrant transgressions of the man who blithely calls himself "the beast of Boonville." In 1988, Anderson went to jail for punching a local school official who had called him a "third-rate McCarthyite." That same year, he published a made-up interview with local congressman Doug Bosco in which the unsuspecting baby-kisser supposedly described his constituents as clueless potheads. This was supposed to be satire, Anderson maintains. Too bad nobody got the joke.

The newspaper graveyard is ever growing: the Rocky Mountain News, The Baltimore Examiner, The Honolulu Advertiser. There is even a website, Newspaper Death Watch, devoted to print journalism's protracted demise. Yet as big-city papers die, small-town papers like the AVA appear to be thriving: A 2014 study from the Reynolds Journalism Institute found that, in nonurban areas of the United States, "67% of the people interviewed read a community newspaper at least once a week." Al Cross of the Institute for Rural Journalism and Community Issues at the University of Kentucky explained to a Stanford researcher that the "community newspaper business is healthier than metro newspapers, because it hasn't been invaded by Internet competition." For better or worse, the San Francisco Chronicle just isn't going to treat the UFOs-over-Boonville controversy quite as thoroughly as the Anderson Valley Advertiser.

But that may not be enough to save the little guys from the little places. To some, even in beloved old Boonville, Anderson is an anachronism, as charmingly obsolete as the faded signs and decrepit buildings that haunt the edges of what may be only charitably called downtown. At the Boonville Hotel, a popular destination for Bay Area day-trippers, copies of The New York Times and The Wall Street Journal lay in the sun, reposing like fattened felines. Issues of the AVA were hidden away in a corner, nursing grievances in afternoon shadows.

Across the way, at the Boonville General Store, a young woman relaxed with a novel. She had moved to Boonville two months ago, yet still hadn't heard of the AVA, which is published only a couple dozen feet from where she sat. All around her, young couples in sunglasses stared into their screens as warm winter sunlight poured down like liquid gold.

At the Mosswood Market, Dave Chambers, a quinquagenarian from San Francisco who sells wine, pecked away on his laptop. He probably belongs to the odious "Nice People" demographic Anderson reviles, yet Chambers reads the AVA once in a while. Sometimes he even takes it home and leaves it in a coffee shop, knowing some other patron will get a kick out of Anderson's ravings. But like many of those in younger generations, Chambers has no loyalty to any single outlet, getting his largely news fix from whatever source the Internet burps up.

Anderson's deputy, Scaramella, acknowledges that most subscribers are in their 50s, at least, and that the paper has few younger readers—or contributors. Neither he nor Anderson appears to think the paper will last long past Anderson. And so they are like the last two soldiers at Masada, besieged but uncowed, fighting doom column inch by column inch.

Robert Mailer Anderson, who has offered some financial assistance to the AVA (his wife is an heiress to the Oracle fortune), says he has no interest in running the paper, no desire to replace the "American phenomenon" that is his uncle. "It will exist beyond Bruce," he says, "but it won't be Bruce's AVA." He thinks that given the growth in the area's Latino population, a Spanish-language section might make sense. He suggests that his daughter, Frances, might one day edit the thing. Alas, she is only 10.

A slightly more credible line of succession has 49-year-old Zack Anderson, son of Bruce, assuming control of the AVA. Zack has contributed to his father's newspaper and confirms that the "vicious rumor" about his eventual editorship is true. Anderson is responsible for the 2008 film Pig Hunt, about "a murderous 3,000-pound black boar" terrorizing a remote Northern California hamlet. I suspect that nothing could prepare him better to fill the pages of the AVA.

But whatever may transpire 30 years hence, when Justin Bieber is the prime minister of Canada and Ryan Seacrest is our leading public intellectual, Bruce Anderson harbors no illusions about the Anderson Valley Advertiser. "Outback newspaper publishing is a fool's game," he wrote in his memoir, "and I'm right where I should be—old and broke in Boonville."