As the plane soars above the Pir Panjal range, you sometimes feel it may tilt, lean, even free-fall, into the valley of Kashmir. These signals of arrival are a leitmotif, felt and learnt over a lifetime. Back in poorer, student days, it would take a 24-hour, tortuous and breathtaking bus journey from Delhi to reach the large green bowl in the mountains where your home and the past, which sometimes swap places, await.

Last November, as I made my annual or biannual journey, I was also on the lookout for something else. What had the floods which swept through Kashmir in September left behind? Would I see a land ravaged, unrecognisable? As we approached the airport, I did notice a change in colour, in the topographic face. Large swathes seemed flat, bearing the clay monochrome of washed-away scapes. But soon tin roofs shone through the doleful sight. From London, I had of course learned that Kashmir had survived the greatest flood in more than a century, but it had been near-death for many people, including my aunt, stranded in her house for three days.

As someone who's changed cities a few times, you wonder about the relationship between memory and present, the sensory and the noetic, between the self and city, and it's evident in the struggle to capture individual moments. When I come here, I visit two cities at once: one that I'm seeing, stepping on now, and the other, back in the hazy but ever-present past.

On the last evening of my visit – when I held a book-reading in a vacated top-floor restaurant because all other venues were flood-affected – I found myself at the gates of the shrine by the river Jhelum that runs through the heart of Srinagar. This shrine is historically Kashmir's most significant but for me also a place of childhood, a hiding space away from the din of commerce and politics and life.

It was autumn, late autumn, when the summer and the devastating floods had receded, leaving behind a quieter, washed-out city waiting for the long and harsh winter. Looking at the melancholic, mysterious façade – old and dark – my mind went back to the time when I used to come here on Eid, eager to spend my festival money on toy pistols and fried snacks, one among a busy, happy crowd of children from around my maternal home in the old city, or "Shehr-e-Khaas" – the real city, as it's more properly known. This is where the Shah Hamadan Shrine, a monument to Kashmir's Muslim heritage, sits by the river. It was built in honour of the 14th-century Sufi saint and scholar Mir Syed Ali Hamadani who had fled from western Persia to escape Timur's persecution. With his arrival began the third panel of Kashmir's rich historical triptych, the other two – Buddhist and Hindu – preceding it. A small ancient Kali temple nests under a mulberry tree behind the shrine.

Soon, I was walking around it, then inside, then closer to the reliquary. This place sometimes helps me trace the arc of my life, from the time I would watch nimble boys swim across the river and see the magnificent sprawl of the fisherman's net, to the years I somehow managed to weave a novel-length story around it. At such moments, when you sense the profound weight of history before you, you also begin to feel the inadequacy of direct and metaphoric expression. The boy who used to trawl the city's streets and dark mohallas and the writer who has perhaps never left the city are in a constant state of negotiation.

I also went to the Nagin Lake, the smaller, quieter consort of the more famous Dal Lake. I always come here, to recapture vistas, animate scenes and conversations from childhood when I used to play cricket here and swim and fish. Or perhaps I come to relive, force even, an act of musing that may encompass it all in one unbroken chain of thought, remembrance.

Predictably, I always fail. There may be a reason for this. The Nagin Lake is a little marvel, quiet, with a small postcard bridge in the near distance, beyond which it opens up into the larger lake, on whose shores are the majestic Shalimar and Nishat gardens, exemplars of the Mughal fetish for terraces, at the back of which rise the Zabarwan Mountains. A little over 20 years ago, I could see this landscape uninterrupted from our third-floor window, more than a kilometre from the lake. Now there are only roofs and underwear. But at least the dusty, treacherous cricket ground by the shore has been transformed into a tastefully done public park. I mention this because it's among the very few signs of love for a city often left to the dogs, both by its callous, venal rulers – client elites trusted by Delhi – and its people.

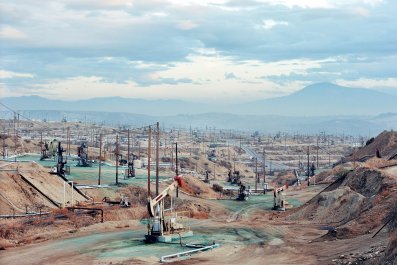

The gradual destruction of this once glorious city of grand bridges, Venetian waterways and bazaars, gardens and orchards, verse and music, was perhaps most evident, in all its horror, during the floods. Decades of neglect of the river Jhelum and its flood channels, its embankments, as well as, most lethally, the filling-up of flanking marshes and reservoirs, led the river to heave to biblical volumes, nearly submerging the entire city.

Going through the centre was painful, the only response being silence and despair. The once bustling market square of Hari Singh High Street now resembled a street of ashen mourners. I walked through the main thoroughfare, MA Road, and recalled scenes on TV that had showed all of it under water.

A city in ruin can be a lesson both in tragedy and hope. Never again, you hear someone say. Kashmiris had risen up against the cataclysmic waters, helping each other and stranded tourists, even the enemy – the occupying Indian soldier, who did also help the population – in some cases. Amid all the destruction and ominous threat of disease, this had surely been a life–affirming moment.

This wasn't meant to be a testimony to loss. Travelling to the place that comes closest to home fills you with a sense of fragmentation; it's of course not helped by the fact that home is devastated by conflict, that it remains a colonised space.

Like most old cities, Srinagar is many things at once but what often stays in my head now is a city of thwarted dreams. The remnants are everywhere: in the desiccating waterways, in the frequent reimagining and remaking that the state attempts from time to time. Two years ago, I found a whole line of houses hollowed out, the latest gift from town planners bent on decongesting the old town. Remove entire rows of homes to widen the road. It is hard not to suspect the road is widened also for easy access to the police tasked with breaking strong pockets of resistance to Indian rule and to snap the old connections within the city. It may well be just a nostalgist's lament, but the floods did show up a choked, suffocated city. The waters, with nowhere to go, refused to unswell for weeks.

The floods last year were a stark, portentous reminder that this is a city in the midst of mountains, surrounded and interspersed by water – no, made by it.