"911, what is your emergency?"

Thanks to depictions in television and film, that is what most Americans think dispatchers say when answering an emergency call. But in reality, dispatchers more often ask: "911,where is your emergency."

The reason this question is asked first is simple: America's 911 system is still fundamentally what it was when it was designed (for landline calls) in the 1960s, when an address was associated with each call. With the dramatic shift toward handheld devices, though, the government required telecommunications companies to come up with a new system to locate callers.

Americans dial 911 an estimated 240 million times a year, and 70 percent of the calls are made on cellphones—a percentage that is only expected to rise. Wireless carriers rely on "triangulation" to approximate the emergency caller's position, comparing the signal strength and time the signal takes to reach a number of cell towers. But triangulation is an imperfect technique.

The spread of cell towers is irregular. If a caller is in a dense, urban setting, there will be more accurate location data because there are more towers nearby. But these areas are also filled with possible obstructions—signals can scatter off anything from buildings to trees. And wireless calls made from indoors pose the biggest hurdle to getting accurate location data.

On July 21, 2014 a woman in San Bernardino, California called 911 at around 11 p.m. to report that she had been attacked in her apartment. The victim, later identified as 26-year-old Michelle Miers, made the emergency call from her cellphone, and law enforcement was unable to pinpoint her location. Information provided by her wireless provider placed her only within a one-block radius.

After 20 minutes of searching, police deduced she was in an apartment complex, and officers eventually spotted a shattered sliding-glass door and Miers inside, covered in blood. She was immediately taken to a local hospital, but succumbed to her stab wounds shortly after arrival. Police said at the time that if they had known Miers's exact location, they could have brought her to the hospital earlier and potentially saved her life.

Miers's story is not unique. About half of 911 calls on cellphones are placed from indoors, and an estimated 60 percent of all mobile calls come with either inaccurate location data or none at all.

In 2006, the FCC decided to require increased accuracy in location services for wireless calls. But the FCC was "not really going to grade them on how well they performed indoors because they weren't really sure the technology would reach indoors," according to Jamie Barnett, former chief of the Federal Communications Commission's Public Safety & Homeland Security Bureau (2009-2012) and current partner and co-chairman of telecom and cybersecurity at Venable LLP.

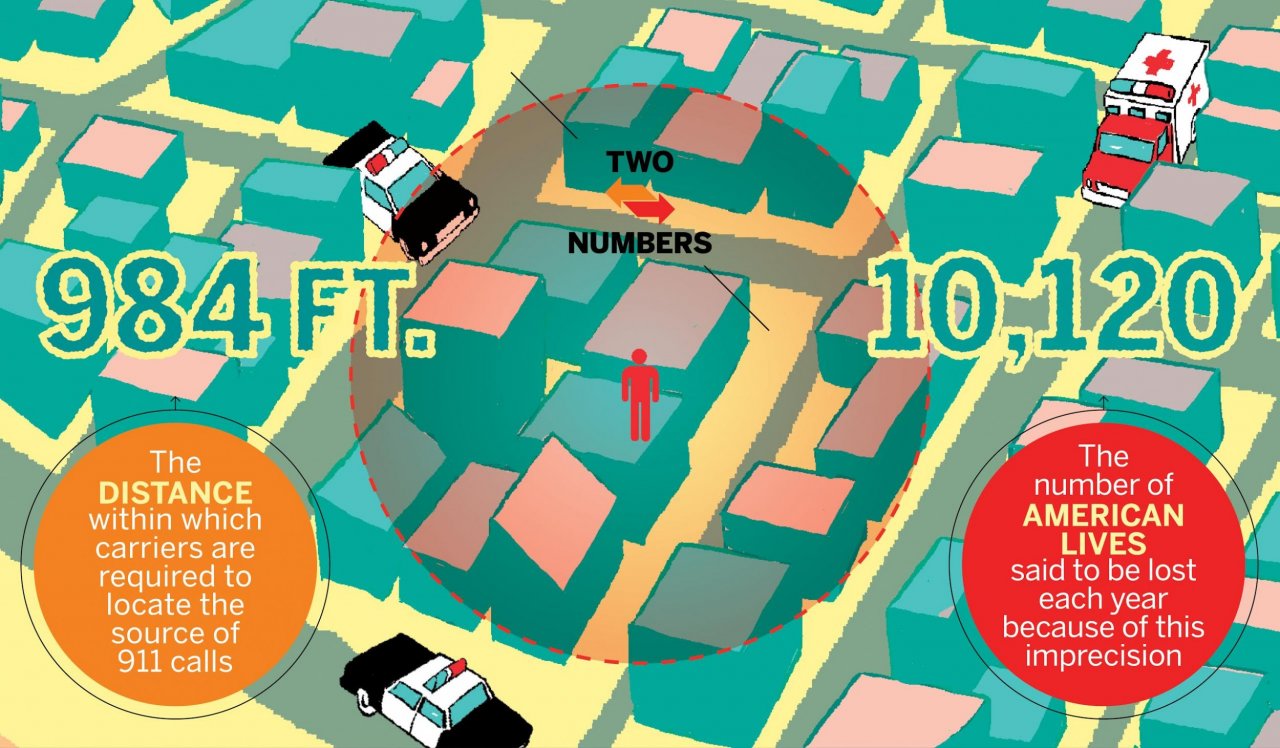

Under the FCC regulations, carriers were required to provide emergency services personnel with a cellphone's location within about 984 feet (300 meters), more than three football fields. A 2013 study cited by the FCC in 2014 estimated that about 10,120 American lives could be saved each year if the location data that wireless providers transmitted to emergency responders was more precise.

The FCC initially proposed to improve the indoor location of wireless 911 calls over the course of five years. After two years, telecoms would have to provide horizontal-location information to within 164 feet (50 meters) of an indoor caller, and vertical information (like what floor of a building someone is on) to within about 10 feet (three meters), for 67 percent of emergency calls. After five years, that level of accuracy would be required for 80 percent of indoor emergency calls. But those rules were never implemented.

"It is very fragmented and decentralized...and you have a lot of jurisdictional politics," says Blair Levin, former chief of staff to FCC chairman Reed Hundt (1993–1997) and current fellow at the Brookings Institution, of the 911 system. He adds that it is much more difficult to incorporate technological innovations into a marketplace where government is the main buyer.

But Barnett casts blame in a more pointed direction. "The FCC so far hasn't enforced rules because it costs the carriers money," he said. "There is not good visibility on the cost/benefit analysis on this because there is no one who can really stand up to the carriers and make the case."

In filings sent to the FCC in reaction to the proposal, AT&T said the changes would "waste scarce resources." Sprint said the standards were "not achievable using current technology."

Barnett disagreed. "Technologies exist now that can provide a vertical location so the question is how fast can the companies implement them," he said.

Closed-door talks between telecoms and organizations that represent public safety and 911 officials, however, yielded an agreement with less restrictive terms, said Barnett.

On January 29, 2015, the FCC voted 5-0 on a 911 improvement roadmap that after two years requires companies like AT&T, Sprint, T-Mobile and Verizon Wireless to provide horizontal-location information to within 164 feet (50 meters) of all emergency callers in 40 percent of cases. After five years, that level of accuracy would be required in 70 percent of emergency calls. The clock for improving location information begins ticking on April 3.

"It is a combination of indoor and outdoor calls," Barnett clarified. "If you boost your accuracy outdoors you don't have to work as hard on your accuracy indoors. It is a much more favorable schedule for the carriers." He added that language in the new regulations asks for vertical location "when possible," which "push[es] back the issue of vertical location for years."

The pressure on the carriers may ease even more thanks to RapidSOS—a new app aimed at improving emergency services that fits within the existing 911 infrastructure.

"Despite the fact that your phone knows precisely where you are located, there is no way with the current 911 system to get that information off of your device," says Michael Martin, co-founder of RapidSOS. "The phone is using a combination of GPS, cellular triangulation, it is also using Wi-Fi hotspot...that's why Google Maps and Uber generally have a very accurate understanding of where you are located."

The RapidSOS app, which requires very little bandwidth, is similar to Uber in how it takes location data off devices, but it also includes elevation and transmits the data directly to 911 dispatch centers. When downloading the app, RapidSOS asks for additional optional information that can also be sent in the event of an emergency, such as name, contact information and medical history.

Also, RapidSOS manages more challenging emergency communication situations, like those in which a person is unable to speak or there is weak cellphone service.

The app's interface comes with four main buttons; fire, police, medical and car crash. Once pressed, the phone automatically transmits the relevant data to the nearest dispatch center. If the connection is too poor to transmit data, the app works to reestablish a connection.

Despite the time it takes to open the app and a built-in 5-second delay (a buffer time to cancel accidental triggers), Martin says 911 callers get through to emergency responders faster with the app than by calling. By removing the location conversation and therefore any confusion as to which dispatch center a call should be sent to, Martin claims two to four minutes of time is saved.

"I just immediately said to myself that this is the product we've been waiting for," said Levin.

RapidSOS is not without competition: There are Life Alert and Onstar, for instance, but these services cannot transmit data directly to 911 call centers. And among other mobile app companies, "all of them except for one are more attractive interfaces for dialing 911," says Martin. "There's no enhancement on location, there is no active management for a situation where a user couldn't speak on the phone...they maintain the normal challenges of navigating through the existing infrastructure with a regular mobile call."

The biggest competitor, according to Martin, is Rave Mobile Safety, which he says requires dispatch centers to use a unique web platform and costs thousands of dollars to adopt.

Martin's app will be free of charge for both dispatch centers and mobile callers. Currently in beta testing, RapidSOS is expected to become available by late August. The team plans to make money and create a sustainable business by offering a premium version for a few dollars a month. The perks are still being worked out.

Although both former FCC officials see great promise in the product, Levin has the standard reservations: "The problem with any solution is that it is done in a lab," he said. "It may have issues in real world application—you just don't know."