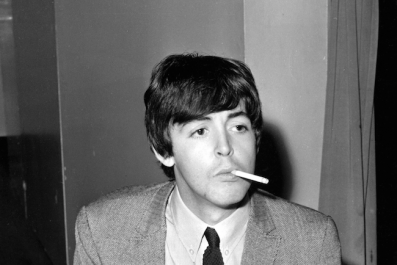

We've all done something for money we'd probably like to forget.

I was hired once by a Big Tobacco company to do a magazine that had nothing to do with cigarettes. It was to be filled with stories and images of men out in the wilderness, on the road, in the desert, but always…alone. The subtext being Here you can smoke without being annoyed by pesky people. Kind of like being dead.

"That's what Marlboro Country is," says Matthew Weiner, creator and showrunner of AMC's Mad Men. "It's a nonspecific drug state that is probably like heaven."

Mad Men made the link between commerce and ecstasy explicit. "Happiness is the smell of a new car," said Don Draper (Jon Hamm), creative director of the fictional advertising agency Sterling Cooper. "It's freedom from fear." Go back and watch the very first episode ("Smoke Gets in Your Eye"); Don must come up with a way to sell Lucky Strikes in the wake of the 1960 Reader's Digest report linking cigarettes to cancer. Various strategies are discussed, including one that leans on America's "death wish" as a selling point. (The client is not impressed.) Don, of course, rescues the meeting and comes up with a pitch that emphasizes the process of making Luckys ("It's Toasted"). And when the client protests that all cigarettes are toasted, he counters, "Everyone else's tobacco is poisonous. Lucky Strikes are toasted." Allowing consumers to deny death another day.

Weiner and I are talking in a room next to the bar in Hollywood's Chateau Marmont, a hotel with its own death association (it was here John Belushi OD'd in 1982). He is in the midst of publicizing the show's final run of seven episodes, starting April 5, and is eager to talk at length (over two hours) about the arc of the show, Don's decline (and resurrection), the relationships between key characters—everything but the actual plot points of the first episode of the final seven. He's OK with mentioning the title —"Severance"—and all the word implies. Death has a cameo. "It's about the life not lived," he says of the episode.

"People on their deathbeds often say, 'I wish I had spent less time worrying about what other people wanted me to do or thought of me,'" says Weiner, who's clearly talking about choices he made on the show, and his sometimes seemingly perverse need to defy the audience's expectations. "I always use the example of a guy who goes to a party, meets a girl, she gives him her phone number and he loses it," he says. "In a TV show he'll go back to the party, find it in some way. InMad Men he will never see her again."

Audiences have come to love Mad Men for a number of reasons—the women, the drinking, the fashion, the design, the drinking, the sex, the music, the drinking and, yes, the smoking—but its dance with death is not high on the list. But we learn early on that Don has taken the identity of a dead man and in the first season he can come off like a matinee idol Camus, saying things like, "You're born alone, you die alone and the world just drops a bunch of rules on you to make you forget those facts." The tension between those stances—cold-eyed realism and the sunny sell— has propelled the series through seven mostly stellar seasons.

Persistently confounding audience expectations would have been a death wish in the pre-Sopranos days of television, but for Weiner, who worked on that show (the script for the Mad Men pilot got him the job), it's not about giving people what they want. "[When] I was on the Sopranos, people wanted to know: When's Tony gonna whack somebody? I like action, I like tension but I didn't need to see somebody's brains on the window every week."

The Mad Men equivalent might be Don hitting on every woman he meets. When I tell Weiner friends have called me, disappointed, when an episode ended without Don playing the Lothario, he laughs. "Like him sitting next to Neve Campbell [on a red-eye to L.A. in the season-five opener]—everything about her was the ultimate Don Draper catnip. Right down to her being single and a little bit depressed. And he doesn't want to do it."

At that point in the show's arc Don had already blown his first marriage, written an open letter to The New York Times saying the agency would no longer handle tobacco (blindsiding his partners) and run from a mature relationship with an understanding psychologist by marrying his new secretary, Megan (Jessica Paré). For some viewers, Don marrying Megan was the Sopranos equivalent of whacking Adriana, but for Weiner the choice was obvious. "What I realized is that [men of Don's day] don't stay single very long," he says. "It's said in the show, they want a steak on the table. Which is why Dr. Faye [the shrink] says, 'You'll be married within a year.'"

That was a bad year for Don (November 1964 to October 1965 on the show's calendar). Recalls Weiner: "I remember Jon Hamm saying to me, when he slept with the two women in one night and forgot to pick up his kids and stole a guy's idea, 'Please tell me this is the bottom.' And I said, 'Almost!'"

"He's got a lot of alcoholic behavior that is not related to drinking," he says of Draper. "He starts to see the signs pointing to marrying this woman. The thrill of the impulse, that moment of reality, of being saved... It's impulsiveness; it's a really big part of his character." [It's Don's partner, Roger Sterling (John Slattery), the show's Falstaff, who speaks for much of the audience upon hearing the news: "Who the hell is that?"]

I thought the moment Don decided to marry Megan was when his daughter spilled her milkshake and Megan didn't freak out, as her mother, Don's ex, Betty (January Jones) would have. "And they're all stunned," agrees Weiner. "But guess what? She doesn't have any kids." He laughs. "I'm kind of on Betty's side with that. Really? Can't I take you anyplace nice?"

Weiner has had a long-standing tradition of talking at length to principals Hamm and Elisabeth Moss, who plays Peggy Olson, a nice girl from Bay Ridge when we met her seven seasons ago, on and off the set. "He used to call me at night and we'd talk for two or three hours sometimes," Moss tells me on the phone from New York, where she is starring in a Broadway revival of Wendy Wasserstein's The Heidi Chronicles. "There was stuff he shared about where things were going and where he wanted to go with it."

The women's stories—and not just those who sleep with Don—are a big part of Mad Men. Those who felt the show fetishisized the '60s Rat Pack, ring-a-ding culture of male chauvinism missed the signals in the first season that blacks, Jews, gays and women were at the gate and the '50s were ending. "She has the upbringing of the '50s, but the counterculture is sort of crashing in on her," Moss says of her character. "Like I don't really feel like my mom but I don't really feel like one of those kids living in the Village and protesting and listening to Bob Dylan.… Another show might have shown Peggy as this sort of bra-burning radical protester but because our show doesn't go in the normal direction—in the direction that you think, ever—Peggy just kind of dips her toe in it and leaves it to go on and become her own person. And that's actually much more realistic."

Becoming her own person is, in an odd way, a gift from Don. "I think they sort of start off as polar opposites," says Moss. "I almost picture him at the top and her at the bottom. And they kind of start moving toward each other as he goes down and she goes up and at some point they meet in the middle.… But Peggy kind of becomes what Don never could become—because he's from a different generation, because he's a man? I don't know why. But she kind of becomes more fully developed than he ever became, she kind of becomes smarter than he ever became. And a bit more able to handle herself in ways he wasn't able to handle himself. And I think that is something that he gave her and taught her and helped her to achieve. She surpasses him and leaves him behind a little bit."

No one wants to see the hero get left behind—though that may just be another example of the show's boy-meets-girl/boy-loses-girl ethos. After Don bottomed out, in the fourth and fifth seasons, audience enthusiasm for the show seemed to cool a bit. (The Sopranos, a major ratings success for HBO, lost viewers before its sixth and final season, too.) Of all the stellar shows of this new golden era of television, Mad Men always seemed to know where it was going, even if its creator was scrambling to fill in his hero's biography early on. The seasons seemed like chapters, and there was a plausibility to much of the characters' fates: An alcoholic found AA, the eldest partner died. Weiner's a literary guy—Don starts off living in Ossining, not exactly the garden spot of upstate New York, because John Cheever lived there, and when I tell him that I interviewed Richard Yates many years ago, not far from where we are sitting, we go off on a tangent about Revolutionary Road ("If I had read this book, I never would have made this show"—a revealing statement perhaps, since Yates's tale of an adman's marriage ends quite tragically) and his lesser-known Disturbing the Peace, a Lost Weekend–type novel of a writer losing his marbles behind booze and his pursuit of art, fame and women ("It's like the Mad Men version of the New Testament to me"). Weiner claims he always knew where his story was going, if not how it was going to get there.

Early on, the people at AMC wanted to know more about Don. "What they said was, 'What else is going on in the show? Who is this guy?' You don't have a Dr. Melfi [Tony Soprano's shrink] and we're not going to have one because part of the story of this show is that these men don't talk to anybody, and Don's never going to see a psychiatrist." (Date one, sure.) "I was emboldened by working on the Sopranos; I did not want to have a formula. But when they got to second episode and there was no big pitch from Don saving the day, they were kind of disappointed."

That's when Weiner came up the backstory of Don actually being Dick Whitman, an ex-GI who stole a dead man's identity in Korea. He cribbed it from an unfinished screenplay he had written in 1992 and presented it to the suits. "I had the best meeting I ever had in my life," he recalls. "I told them this story, which was so intricate and long and detailed, and they were like, 'Did you just make all this up?' And I didn't tell them…. I didn't tell anybody for years."

Weiner knows that coming clean doesn't necessarily make for good drama. Don is pushed out his own company in season six after confessing, in a meeting with Hershey's, that his childhood was a horror and he is not who he says he is. He has to work his way back into the company he helped build, make amends to his partners and Peggy, make peace with his daughter and even his ex. "Watching him go from someone who didn't want to be a partner because he didn't want anyone to know his name to a guy with his name on the firm, reluctant to take his name off the firm"—that journey was a tough sell to fans at times. "I wanted to show him change, which is in itself against the very principles of serious television."

Weiner's not too worried about how the audience will react to the show's concluding scenes, and I doubt it will end in Don's death (though a lung cancer diagnosis is plausible). Though Weiner works with a large team of writers, it's still his show and Don's his guy, and both are a little less free with the sort of Existentialism 101 sentiments they espoused early on. "You just stop having a confident attitude about the meaninglessness and disorder of the universe," he says. "Some of that is about having children but I do think it's also about getting older."

Mad Men has come this far not talking down to the audience, not explaining every action and omission, not connecting every dot. "I showed [Stanley Kubrick's] 2001 to my children because they're really into space," he recalls, "and I really thought, I'm pushing it here. My oldest son was 16 and the littlest was 8. First of all, they could not get enough of it, the monkey stuff, all of it. But when the movie ended I asked the 8-year-old, what is the ending? What does it mean? And he said, 'Well, I think he became something else.'"