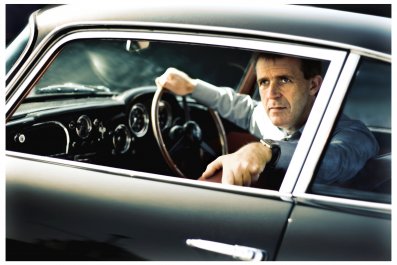

On a beautiful autumn morning not far from where Rosa Luxemburg's body was found in the Landwehr Canal, a compact, grey-haired man springs out of a taxi and peers about through red-framed glasses. He is dressed in black ("it doesn't date") – black jeans, scarf and jacket ("from airports usually") – and on his feet wears crocodile-skin cowboy boots ("from Albuquerque"). Hand outstretched, he walks towards where he asked us to meet, on Potsdamer Strasse, outside Mies van der Rohe's Neue Nationalgalerie.

Like van der Rohe, Daniel Libeskind is a great architect. His initial choice was a walk from his studio in New York to the Ground Zero site, of which he is master-planner. But he changed his mind, preferring to set out from the Neue Nationalgalerie, now closed for renovation, to the Jewish Museum. Libeskind's first major building to be completed, it opened on 9 September 2001, in one of those arresting combinations of fate that seem to have tracked him since his birth in Poland 68 years ago.

We head off through the centre of Berlin, where in another momentous year – the summer of 1989 – Libeskind arrived to start work on the Jewish Museum. Three months later, the Wall came down.

Our path this morning is a mere five miles, but its route through Berlin's once-divided city is a walk in the shadow of events that have shaped Libeskind's life but also his works; notably, the museums he has built in Berlin, Dresden, Copenhagen, Denver, Toronto, San Francisco and Manchester.

Libeskind grew up in Lodz, where he was born just after the war. His family were Ashkenazi Jews from Eastern Europe, his grandfather an illiterate, itinerant Yiddish storyteller. Samuel Johnson said that "very few men know how to take a walk". Walking and talking were instinct in Libeskind from the start. "I'm not that old, but there were still horse-drawn carriages, no cars.

I used to walk to school, or with my father to the Jewish cemetery – the biggest Jewish cemetery in Europe – trying to interview anyone who was Jewish and had survived. I held my father's hand as he went up to people and asked, like a code, 'Are you of the people?' and broke into Yiddish. But there was no one left."

Together, they faced the Sisyphean task of cleaning up and restoring the ignored tombs of relatives and friends. Of Libeskind's immediate relatives, 85 had been exterminated.

His parents had survived by fleeing Poland when the Germans invaded in 1939. Captured by the Red Army, his father was marched to a camp in the Volga; his mother to a gulag in Siberia. "She had to sew white silk shirts for officers. The only way to protect against frostbite was to wrap newspapers around her feet." Years later, at the family table in the Bronx, she declared the Soviets were just as bad as the Nazis – only not so efficient.

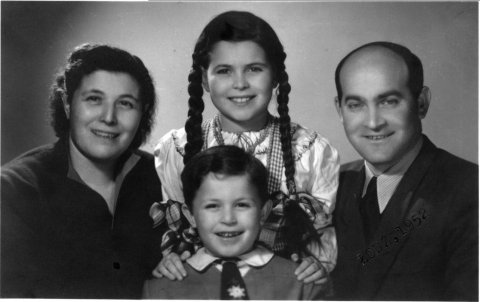

In 1942, under the terms of a Polish-Russian treaty, both parents were released. Independently, they travelled east, towards warmth, ending up in a small community of Polish Jews on the Tibetan border, where they met, fell in love, married.

In late 1945, pregnant with Daniel, his mother decided to return with her husband to Poland. The epic journey home took nine months. Daniel gestated in movement: on hitched rides on freight trains and horse carts. "Other times they walked." From Tashkent. Through the Fergana Canal to Moscow and Minsk. To Lodz. "I was born the day they arrived."

His mother Dora was a seamstress. In Lodz, she specialised in sewing underwear for women – nude-coloured corsets and girdles for the wives and mistresses of Party members. Daniel inserted the whalebones – his first lesson, he jokes, in applied Euclidean form. "Her shop was a hole in the wall with one small door – this size," and he stops before a new office block and spreads his arms over a glass pane. "She had one Singer sewing machine, and the police would come checking lists. 'How much do you pay for this? Where from?' There was a sense that to be involved in private enterprise made you an enemy of the state. It's hard to believe in my lifetime."

His father, Nachman, found work in a textile factory. He was shivering, coatless, in a queue of men trying to land a job, when a man walked down the line, shouting: "Libeskind! Where is Libeskind?" He was terrified, his son says. "One must never be identified. Once they had your identity, it usually meant trouble with the Polish secret police."

Before the war, Nachman had been arrested for whistling in public, and thrown into a prison cell with 30 others, charged with sending a secret message. Through a hole in the thick wall, he established communication with another prisoner, a communist. They revealed their lives through a knocked Morse code. Nachman, a non-smoker, blew his daily cigarette-ration through the hole to his invisible friend. Now told the factory boss wanted to see him, Nachman was ushered into the presence of a man who

gave him a tearful embrace. As explanation, he rapped his knuckles in a pattern on the desk – he had waited so long to meet Nachman Libeskind! It was the man from the other side of the wall, who offered Nachman the job of manager.

I ask, "What do you remember about Poland?"

"The grimness. Coupled with a sense that the Holocaust was not over. At school, my name alone was enough. The other boys used to hit me. I'd run back home not to get hit. I was always in flight."

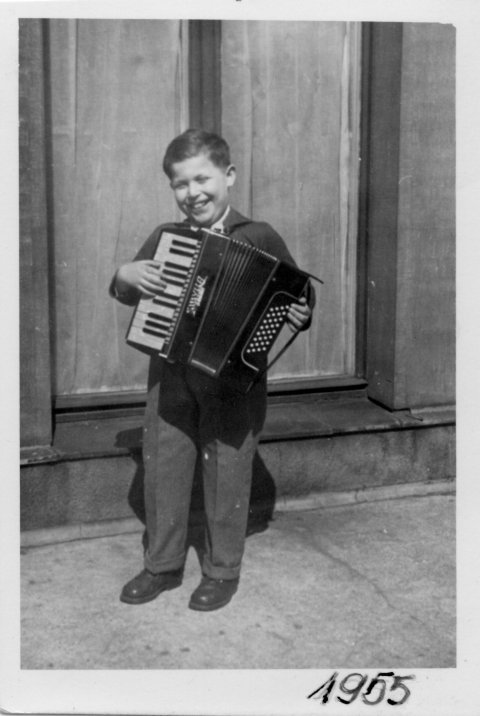

What rescued Libeskind was music. Aged five, he had longed to play the piano. "But my parents were scared. A piano was too big to get into our little courtyard, and we would be targeted by our neighbours. So my parents brought me a suitcase. 'OK, we've got you a piano' – and inside was an accordion."

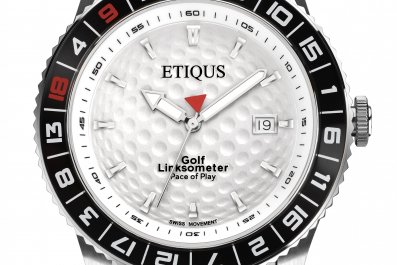

On his white Hohner, Libeskind proved a child prodigy. In 1953, between hymns to communism, he performed Rimsky-Korsakov's Flight of the Bumblebee on the first ever broadcast on Polish television. He was such a virtuoso that upon arriving in New York in 1959, he won an America-Israel Cultural Scholarship, playing a red Sorrento. One of the jurors, violinist Isaac Stern, wanted to know how Libeskind had got stuck with the accordion: "You've exhausted all the technical possibilities of the instrument."

Not long after, for reasons he still is unable to explain, Libeskind gave it up. His wife of 46 years and his three children have never heard him play a single note. He managed to discover an alternative outlet, first in drawing, then in architecture, sketching out his designs on musical notation paper. "Architecture is very similar to music. Every vibration, every line has to be perfect and precise. At the same time, you're working with others. Unless you work like Speer for Hitler, you have to be part of a consensus."

We halt before an imposing 1930s construction in what was the Soviet Zone. The German Democratic Republic was declared inside this grey building. Before that, it housed Goering's Luftwaffe. The long narrow windows are typical of the totalitarian design favoured by Albert Speer, the Führer's favourite architect and collaborator.

"Architects like authoritarianism, so they look for powerful clients who can get their projects built. Stalin loved architects – Beria trained as an architect. Mao and Hitler had great architectural aspirations. Hitler wanted to destroy half this city to build the world's capital, and Speer, the lackey, would make his dream come true. Even in his bunker at the last minute Hitler was looking at models of his new Berlin."

Today, the Reich's former Aviation Ministry contains the German Finance Department. Libeskind is impatient to press on. "Even though nicely restored and cleaned, it gives me the creeps to look at it."

"Why is it bad?"

"This is art without any ethics; it's the building of a fellow traveller, an expert manipulator. You recognise the meanness. The proportions are mean. Everything is fake, mechanical, and invented through the classical style. There's no human spirit. Aesthetic desire is the opposite. It's an affirmation of the diversity of life, of the sky, of the earth – and not of a fantasy of oppression."

We turn right. Next lane is Niederkirchnerstrasse. On one side is a grey façade, the surviving remnant of the Gestapo and SS headquarters. It provokes Libeskind to imagine the opening night, the canapés and luminaries, the orchestra playing, art critics united in praise. "This was going to be world's capital for 1,000 years. It didn't even last 10. Now look at it. We see it for what it was, an exercise of evil."

He breaks into verse, quoting Emily Dickinson, his favourite poet:

"Fame is the one that does not stay –

Its occupant must die."

Glimpsed at the end of the road is the reddish façade of the Martin Gropius Museum, to which, in 1990, Libeskind was invited to contribute an installation for an exhibition on Soviet and Nazi art. Its gem was a letter he wrote to the French philosopher Jacques Derrida: "I would like you to give me the answer to a very simple question. What is the most important date in the 20th century?" Derrida replied: "23 Aug 1939" – the day of the Hitler/Stalin pact. Libeskind says: "That was the end of the world. Those two colliding deviants of history had divided it. I built two mega wedges, one black wedge closing in on a big red one. It was one of the most popular exhibitions ever. For the first time, people could see what Derrida meant."

On the other side of Niederkirchnerstrasse is

a rare section of the communist Wall that had appeared overnight in 1961. "The commission would have been awarded to an architect like Speer. 'I'm going to do a great job on the Wall!' Buildings in concentration camps were designed by good architects for what they had to do, which was to exterminate."

With a professional eye, Libeskind surveys the graffiti-splattered Wall. "Consideration would have been given to the foundations and materials. It's made of concrete and reinforcement bars, 12-foot high – an empirical height for people not to climb over. And at the top, prefabricated concrete elements to make it more difficult, and you more visible, as you climb over."

As abruptly as it was erected, the Berlin Wall fell. Absorbed in what the city is forcing him to remember, Libeskind fails to notice that he is striding us through Checkpoint Charlie – the spot formerly marking the entrance from the Russian sector into West Berlin. "The Wall went through this. The Wall was right here. We've crossed it!"

In early November 1989, having uprooted wife and children here, Libeskind had invited his father to West Berlin. "Most of the family disowned me when I came to live in Germany, except my father. He understood."

On his first visit to Europe since 1957, Nachman had stopped in Potsdamer Platz, tears in his eyes: "We are here, living, eating, sleeping in this city, and the bones of the Nazis are rotting underneath." They had rented a VW camper-van. On their return through Checkpoint Charlie, on the night of 8 November, three East German police cars descended, torches flashing, and hastily fined the Libeskinds 100 marks before letting them through. "It was the last fine issued. They already knew. Next day the Wall is down."

Vivid in Libeskind's memory is being interviewed, shortly afterwards, on the roof of the Springer Verlag building, and watching bulldozers beneath tear down the Wall. "This city, the source of all evil in the world, was changed overnight, making it such a fantastic new, hopeful city," he says. Fundamental to the new Berlin would be its Jewish Museum.

Libeskind had built nothing before. He was living in Milan, aged 42, an architectural theorist who had worked in architects' offices for a few days at a time and resigned because he was bored. Then in November 1988 a letter arrived, inviting him to enter a competition for an extension of the Berlin Museum to house "the Jewish Department".

The 165 candidates were to submit their designs anonymously, with a number. "I chose six million and one. If the jurors had discovered my name, I'd have been disqualified. They didn't even know I was Jewish." He didn't have to go to libraries for research. "I knew what the story was. Instantly."

Months later, he was lying in bed one night when the telephone woke him. His wife answered. "It's for you." A voice in terse German said:

"Mr Libeskind, you've won the competition."

Rooftops above the skyline recollect the twisting saga of the next 12 years. One by one, Libeskind points them out:

The Senate Building Administration office, where in 1990 the new senator for building, Wolfgang Nagel ("meaning 'nail'") summoned Libeskind. "He comes over to me, puts a finger to my chest and says aggressively, determined to fire me, 'What buildings did you do in the past, Mr Libeskind, to qualify you to do this?' I said: 'If you go by the past, Berlin is not going to have any future.' He put his finger on the model. 'OK, how do I get in?' I said: 'There is no door for you. You have to go underground, because Jewish history is hidden. You must descend.' After two minutes, his eyes had changed, his expression had softened. 'Mr Libeskind, I welcome you to build this in my city.'"

The Senate, which in 1991 decided to scrap the museum with a unanimous vote.

The Rathaus, where mayor Eberhard Diepgen offered Libeskind, instead, the chance of building a skyscraper in Alexanderplatz. Libeskind says:

"I told him, 'I haven't come to Berlin to build office buildings. I came to build the Jewish Museum,' and I walked out, slamming the door."

The Parliament of Berlin, which unanimously overruled the Senate and voted to build the Jewish Museum.

At last, in September 2001, after five changes of name, four changes of government, three changes of director, the building stood ready to open. At a dinner for the chancellor, Gerhard Schroeder had knelt beside Libeskind's father and held his hand, saying, "Mr Libeskind, you must be so proud. Thank you for being here" – "and I thought, there is the German chancellor, kneeling next to my 90-year-old father, in the Jewish Museum."

We approach via a narrow lane that would not exist but for Libeskind. He pauses beneath the sign – "ETA Hoffmann Promenade" – and smiles: "I'm very, very happy that the name I gave this promenade on the plans is here." Hoffmann was a Polish Jew famed for fantasy and horror stories but he also bestowed names on Jews. "Libeskind – love child – is a Hoffmann name."

We walk down the lane. And there at the far end, zinc façade gleaming in the pale Berlin sun, it is.Unrecognised, Libeskind enters. We pass through security, and I follow him down, into the earth. The tilt of the black slate corridor creates uncertainty. At the end, a thick metal door on a sloping surface. He squeaks it open, invites me inside.

We stand in a bare, dark, cathedral-shaped space and look up at a slant of light. He whispers: "You don't see the source. You only see the illuminated surface, reflected on the wall. But I didn't have it till the very last moment. I stood in a model that had no light and thought, it can't be. There's got to be light." Then he read a book about Holocaust survivors living in Brooklyn and a woman who, loaded on to a cattle truck, saw a crack of light through the slats and held on to the memory of it through her dark years. Libeskind realised: "You have to bring hope. Without a positive sense of the future, you can't build architecture – because you're laying foundations."

I first stood here in 1999, before the museum's official opening, and experienced the dislocation that Libeskind intended – "that shock to the system that comes from seeing something jarringly new or unexpected, so that you feel you have arrived in another place, between the known and the unknown". Since then, 350,000 people a year have filed through the same squeaking door and stopped in meditative silence to gaze up at a needle of light.

An immigrant who has found in architecture a way to reflect catastrophic events, Libeskind is drawn in his 70-odd buildings ('the same number as Frank Lloyd Wright!") to explore what he calls "the void: the presence of an overwhelming sense of emptiness when a community is wiped out."

The entire premise of the Jewish Museum, commemorating the obliterated history of Berlin's 160,000 Jews, is in this room, the Holocaust Tower. "It's a building based on absence," he says, again quoting Emily Dickinson: "To fill a Gap/Insert the Thing that caused it." As in his project for Ground Zero, the absence is creative. Out of his void, he has invented an expression for emotion, and, by breaking all rectangular structures, a way to give historical experience not only a form but an optimism. "The light is something that penetrates through, a sharp point where you come to realise something about the past, which is also about the future. Suddenly, you see light in a different way, and yourself too."

Outside, a grey-haired woman turns and peers solemnly at him. "Are you Mr Libeskind? Thank you for having done this architecture."

Over a drink at the Hotel Adlon after our walk, Libeskind mentions that in Paris a cocktail has been invented for him. A vodka from the era of Napoleon. And he talks of a machine that distils the essence of a herb. Another machine, from New York ("Only in New York!"), that creates ice in the shape of a wedge. The cocktail was so good, smokey, mysterious …

"What did it taste like?"

He leans forward and looks up at me. "Nothing."