Ricardo Illescas Ramírez wanted a drink. It was August 2013, and the 25-year-old clothing salesman was in Potrero Nuevo, on Mexico's eastern Gulf coast, in Veracruz state. He had arrived earlier that afternoon to meet with buyers, and when he finished for the day, Ramírez plopped down at a rickety bar near the center of town.

Shortly after he walked in, witnesses say, a group of men in police uniforms burst through the door, dragged Ramírez and several others outside, shoved them into patrol cars and drove off. Witnesses reported similar incidents earlier that day at a nearby park and truck stop. In total, 20 people vanished in Potrero Nuevo that day. None have been seen or heard from since.

Ramírez wasn't the first person to disappear in Mexico, and he won't be the last. Over the past nine years, more than 20,000 people have vanished, according to government statistics. Most, analysts say, have been kidnapped or murdered by drug traffickers or "disappeared" by corrupt members of Mexican law enforcement. The real number is likely much, much higher, because crime statistics in Mexico are notoriously unreliable.

Disappearing without a trace is not uncommon in Latin America. Between 1974 and 1982, at least 10,000 Argentinians vanished during that country's military dictatorship. In Guatemala, an estimated 70,000 people were killed or disappeared in 1982 and 1983 during dictator Efraín Ríos Montt's rule. Mexico, of course, is far from a despotic police state, but over the past six months, the issue of forced disappearance has roiled the country because of the incestuous relationship between Mexican law enforcement and its main adversaries, the country's vicious and powerful narco gangs. As the outrage has escalated, Mexican President Enrique Peña Nieto has promised to restore law and order and bring a sense of closure to the families of those who have vanished.

Yet critics say the government has little to show for its efforts. Eighteen months after those 20 people vanished in Potrero Nuevo, the victims' families still don't know who kidnapped them or why. More important, they don't know if they're dead or alive. "We still have no answers," says Rosa Maria Ramírez Rojas, 48, Ramírez's mother. "No one can tell us anything."

The Saddest Part

It wasn't supposed to be this way for Peña Nieto. Once lauded by the Western press for his attempts to create jobs, the young, telegenic leader came to power in 2012, vowing to move past the drug war, which has claimed the lives of 100,000 people since 2006. For a while, Mexico's murder rate slid to its lowest level in years, and Peña Nieto drove a series of economic reforms through the country's fractious legislature.

But in September 2014, a new national crisis emerged. More than 40 students in Iguala, a city in southern Mexico, disappeared as they tried to commandeer buses to take them to a political rally in Mexico City. Federal investigators swooped in. What they found was disturbing: The city's mayor had allegedly ordered the police to kidnap the students and hand them over to a local drug gang. The reason: The student protesters had been vocal critics of his wife.

The authorities quickly arrested the mayor, his wife and scores of police officers, along with members of the drug gang. But tens of thousands of Mexicans took to the streets across the country, calling for the police to find the missing students. Many demanded Peña Nieto's resignation. The president responded by stepping up his efforts to find the disappeared, or at least their remains.

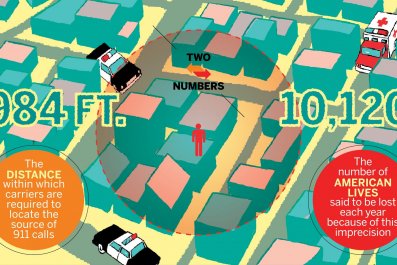

So far, the government has made little headway. One major reason: forensics. More than a decade ago, Mexican authorities set up a national DNA bank, intended to solve a variety of crimes, from rape to human trafficking. The bank has collected more than 25,000 genetic profiles, but as the Mexican government, along with the army, the police and a host of forensic investigators, continues the search in Iguala and elsewhere, fewer than 600 genetic samples have been reportedly matched with their remains.

"The Mexican government has the money and the technology, but it lacks transparency and the will to tackle the problem of forced disappearance," says Ernesto Schwartz, a geneticist and the founder of Citizen Forensic Science, a nonprofit created with grant money to help Mexicans find their missing loved ones. "The saddest part is that the institutions have information, they have DNA samples, but they handle them poorly and don't share their information with others. We are trying to end the monopoly that the state has on the truth and allow the citizens themselves to have control."

Other citizen groups have tried to do the same, and the result has led to further embarrassment for Mexican authorities. Last fall, as frustration mounted against the government's efforts in Iguala, volunteers flooded the countryside, hoping to find the missing students. They didn't succeed, but they did uncover dozens of secret graves, many of which belonged to other victims of drug-related violence. The problem of forced disappearance, the volunteers showed, was far greater than most Mexicans had imagined.

'A Brutal Drug Gang'

Over the past six months, volunteers and government investigators have turned up more and more clandestine graves across the country. But their work has offered little comfort to the relatives of those who vanished in Potrero Nuevo.

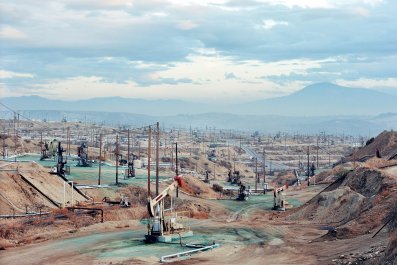

The town is surrounded by lush mountains and vast fields of sugarcane. It's also on a lucrative drug-trafficking route connecting Mexico's northern border to the Caribbean south. Controlling these routes: a brutal drug gang called Los Zetas. "They dominate everything and have deeply infiltrated local police forces, who are very capable of carrying out disappearances," says José Reveles, a veteran crime journalist and drug war expert.

It remains unclear if Los Zetas, along with help from local law enforcement, kidnapped Ramírez and 19 others on that fateful night in August. Several days after the disappearances, the state prosecutor's office issued a short statement saying it was investigating the matter but denying there had been a police operation that day. According to the victims' families, the prosecutor's office has no arrest record for any of those who disappeared. Nearby prisons don't list any of them as inmates, and the authorities haven't responded to numerous requests to see video footage taken near the scenes of the abductions.

"We had meeting after meeting with the prosecutors," says Ramírez's mother. "It felt like they were only keeping us busy. What angers us most is that they reacted way too late when we reported the disappearances and that the ensuing investigation ground to a halt from the start."

I asked Veracruz's state prosecutor's office, the state human rights committee and the office of Veracruz's governor, Javier Duarte, for comment. No one responded. However, not long after my inquiries, the families of the victims say, the authorities contacted them last month, the first time they had done so in nearly a year. They were happy to hear from someone, but they still feel nothing is being done. "We feel abandoned by everyone," says 43-year-old Alicia Hernández Garcia, whose son Kevin, 20, was abducted in Potrero. "I've told my story so many times to so many people, and it hasn't helped one bit."