It is a sunny morning in mid-April on Sicily's east coast, and in the distance Mount Etna rises from a green-blue sea up through the olive groves to reach a snowy cone ringed by cotton ball clouds. In the center of this Mediterranean tableau, at the end of a long quay in the port of Augusta, is a jarring anomaly: a gray Italian gunboat, on whose rear deck hundreds huddle under heavy brown blankets. At the guardrail is a man, perhaps 35, with a wild beard and a baby on his hip. Beside him is a woman in an abaya holding hands with a small girl in pigtails. Their faces are smeared with dirt, their hair is covered with grime, and their clothes, once different colors, are almost indistinguishable under layers of brown filth and white dust. In the bright and sunny surroundings, the refugees seem out of place, like they might belong to another place or time: like an aid poster or a picture of the Holocaust. When a sea breeze carries the scent of this huddled mass ashore, the Red Cross workers on the quay recoil. How is it possible to be still alive and yet smell so much of death?

The Italian navy rescued these men, women and children—mostly Syrians, Eritreans and Somalis—as they tried to cross the Mediterranean. Four days prior, however, 800 others drowned when their boat sank off the coast of Libya. This new group, then, is the lucky ones. Typically, their journey has cost them their life savings and years of suffering. Many of the African children are traveling alone. Others died of dehydration in the Sahara, long before they reached the Mediterranean shore. Some arrived in Libya without enough money to pay for the next stage of their journey. Smugglers held them hostage until their families could be persuaded to pay. "One boy couldn't even count how many friends of his had died," says Gemma Parkin from Save the Children. "Almost all the women have been raped."

'A Fucking Nightmare'

In his second-floor office in the Palace of Justice in Palermo, Calogero Ferrara lights a cigarillo and hands over a 526-page indictment against 24 African human traffickers. A day earlier, not only did the 800 migrants drown 300 miles to the south, but the Islamic State (ISIS) released a video showing what many, presumably, were fleeing: the execution of 30 Christian Ethiopians in Libya. Gregarious and fashionable, Ferrara, an anti-Mafia prosecutor, wears a dark suit, vest and light blue spectacles. He has just held a press conference to announce a rare triumph in Italy's fight against illegal migration. Overnight, his men have dismantled a people-smuggling network and arrested 14 men—mostly Eritreans—in Sicily, Milan and Rome. Ferrara says he expects another eight to be detained in the next few days.

Still, Ferrara has no illusions about the bust's likely effect. Every day, as he arrives for work, Ferrara passes a limestone wall inscribed with the names of 11 Palermo prosecutors assassinated by mafiosi. The Mafia's enduring threat forces Ferrara and his family to live behind a wall of armed security. Seeing colleagues killed and examining bullets dug out of gangsters' faces both pass for normal for Ferrara and his ilk. "But this," he says, referring to the indictment, "this is a fucking nightmare."

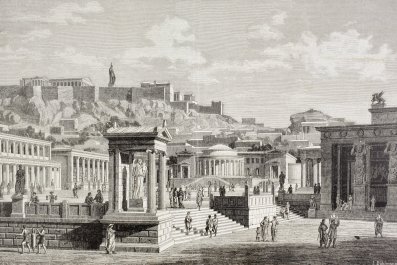

Ferrara's troubles have their origin in Sicily's location. In the center of the Mediterranean, midway between Europe, Africa and the Middle East, Sicily has been one of humanity's great crossroads for thousands of years. Palermo was founded by the Phoenicians in the eighth century B.C., and then conquered by Greeks, Romans, Vandals and Byzantines, followed by Arabs and Normans, then the Spanish, the French, the Italians and, finally, in an invasion assisted by the Mafia, the Allies during World War II.

Sicily's ancient cosmopolitanism, visible in churches incorporating Arab domes and street signs in Italian and Arabic, seems to have saved it from the political and racial tension that greets migrants in parts of Europe farther north. A view of migration as unchanging, unstoppable and even positive also helps explain why, as the number of migrants skyrocketed, the authorities were slow to intervene.

But it does not explain why that inaction continued after the migrants began dying. Since 2000, around 22,000 Middle Easterners, Asians and Africans have drowned in the Mediterranean. Many perished in the seas between Africa and Lampedusa, the small, southern Sicilian island just 180 miles from Tripoli and the closest part of Europe to Libya. In the last 18 months, the number of those trying to reach Europe—and dying along the way—has accelerated. In 2014, more than a quarter of a million migrants tried to cross the Mediterranean, of whom 3,702 died. In 2015, the European Union predicts the crossings could exceed 500,000, a spike the International Organization of Migration is warning could bring 10,000 deaths.

Traffic is rising for various reasons: civil wars in Libya, Yemen, Syria and both Sudans, as well as repression in Eritrea. Europe is not blameless in these disasters. NATO helped depose Muammar el-Qaddafi in Libya, the European Union supported an ethnically divisive government in South Sudan, and both NATO and the E.U. have done little to stop Syria's implosion. Further back in history, as Africans arriving in Europe often remind those who object to "economic" migration, the wealth that now attracts migrants was amassed, in large part, by Europeans who migrated to Africa in pursuit of its riches in the 19th century.

Nevertheless, Europe has reacted hesitantly to the news that the Mediterranean is becoming a mass grave. Italy, its finances still in tatters after the 2008 financial crisis, claims it can afford almost no intervention without European funding. And while Pope Francis and southern European leaders have made appeals to a common humanitarianism, farther north the number of migrants has stoked a surge of anti-immigrant anger that, at its most extreme, persuaded a columnist for the British newspaper The Sun to call for gunboats to blow the migrants back to Africa. Such ambivalence is reflected in muddled action. After 366 migrants drowned when a boat sank near Lampedusa in October 2013, the E.U. paid Italy to step up rescue patrols. These prevented thousands of deaths until a year later, when the E.U. decided the patrols were encouraging more migrants and withdrew its financial support. After the death of the 800 refugees in April, the E.U. reversed itself again, promising to restore the funds. Simultaneously—and even as it criticized The Sun's language—it proposed military action to destroy traffickers' boats and kill or capture the smugglers themselves, a plan quickly denounced by its own advisers.

Such a slow and uncertain response, following equally dawdling attempts to address the 2008 economic slump, has raised questions about the E.U.'s ability to cope with crisis, and even, its critics say, to function at all. If there is new hope, it lies with Italy's elite anti-Mafia prosecutors, who have argued since the Lampedusa disaster of 2013 that because people smuggling is a form of organized crime, and one that affects Italy, this human disaster comes under their jurisdiction. Fabio Licata, a Palermo judge who works closely with Ferrara, says Italy's long experience with the Mafia works to its advantage in this case. "We have the best organized crime investigators in Europe, even better than the U.S.," he says. "Other countries in Europe deal with people smugglers as a police problem or a problem of public order. But this is about crimes against humanity, smuggling, money laundering, even terrorism. We know these phenomena. We know how to fight it. We achieve results."

As Licata admits, however, what Ferrara and other prosecutors are uncovering suggests a fight every bit as dangerous and daunting as any Mafia battle Italy has ever faced.

'A Criminal Operation Like No Other'

Ferrara began investigating people smugglers the morning of the Lampedusa shipwreck. He directed his officers to ask survivors for the phone numbers of the men who sent them on the boat. By tapping those lines and tracing calls to other numbers, he built a phone tree of thousands of numbers with branches stretching from Africa to Europe, the Middle East, Asia and the U.S.

In 18 months, he and his team recorded more than 30,000 calls. Those transcripts, some of which Ferrara made available to Newsweek, point to several new multinational organized crime syndicates together worth around $7 billion a year. They also identify the man who is allegedly among the busiest and most sophisticated of the traffickers: an Ethiopian based in Libya named Ermias Ghermay. "He is a merciless criminal that for money has created a business based on human goods," Ferrara says. Ghermay's network offers "a complete service to migrants, running from the center of Africa to Libya to Italy to another country from there. It includes all accommodation, transport and food." It is, the prosecutor adds, a criminal operation like no other. No name, no fixed base, a fluid membership and, most remarkably, "totally without risk." "With drugs, if you lose the drugs, you lose your money," says Ferrara. "But in this case, you pay in advance. Even if the migrants drown, Ermias has already been paid."

Newsweek was unable to reach Ghermay for comment. His clients describe him as about 40 years old, short and stocky. In conversation, he seems uneducated but street-smart. He's dynamic and fluent in several languages, including Arabic and Tigrinya, the ancient tongue of northern Ethiopia and Eritrea. He has been working as a people smuggler for about a decade. Like many other smugglers, he bases himself on the Libyan coast, mostly in the capital, Tripoli, or in the port of Zuwarah to the west. Importantly for E.U. officials thinking of targeting traffickers' ships, Ghermay already regards the wooden fishing boats and inflatable rafts he buys as disposable: They generally either sink or are confiscated on landing in Sicily. That has encouraged him to seek out the cheapest seaworthy vessels—inevitably, ones that barely float. To combat the chances of his clients either losing their nerve or finding another boat, Ghermay allegedly came up with the idea of renting warehouses in Zuwarah and locking thousands of them inside for months at a time after confiscating their mobile phones. Like many other smugglers, Ghermay organizes his migrants on his boats by race. Syrians pay more to ride on the upper deck. Africans, who typically have less money, are locked down below without food or water.

Most of the smugglers seem content to be merely links in a chain. But Ferrara says Ghermay's calls reveal wider ambitions. To ensure a steady supply of migrants, he frequently reaches out to traffickers in Sudan, Somalia, Nigeria and Eritrea who run trucks across the Sahara. Simultaneously, he is continually establishing fresh relationships with smugglers further down the line: in Sicily, operating inside migrant centers, or in Rome or Milan, or even further afield, in Berlin, Paris, Stockholm or London. These contacts—whom Ghermay flatteringly addresses as his "colonels"—perform two main tasks, according to the wiretaps. They send and receive people and money. Ghermay mostly funnels the cash through international transfer agents in Ethiopia, Israel, Switzerland and the U.S. As part of their service, the colonels also give the migrants a number for the colonel at the next stage of their journey and the latest information on the safest routes.

Some of Ghermay's colonels exhibit entrepreneurial spirit, advertising on Facebook and other sites. And lately Ghermay has diversified, too. For those who can pay, he has built relationships with other contacts who supply fake passports, fake marriage documents and even—using at least one corrupt European ambassador in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia—real passports and real visas, according to Ferrara. For those with a lot of money, Ghermay will even arrange plane travel.

In this way, Ferrara says, Ghermay has built a global network that is a one-stop shop. His representatives around the world can offer transfers from anywhere to anywhere, anyhow, for a single price. This is an empire that is based nowhere, run by a constantly changing personnel, adjusting to new opportunities and overcoming new adversities. Licata, the judge, calls it "an octopus."

The secret of Ghermay's success, according to Ferrara, seems to be his charm. He spends much of his day on the phone talking to families paying for their relatives' migration, offering them reassurances about safety while gently reminding them of their bills. The question of money is especially delicate. Many of the Eritreans are children, often toddlers, picked up from refugee camps in Ethiopia by smugglers who promise free transport to Europe, where they claim an unaccompanied child will be given automatic asylum—and so establish a base where their families can join them. This is a gross mischaracterization of European immigration procedure. It's also a scam. Once the child is taken, the family discovers it will have to pay for transport: around $1,800 for the journey to the Mediterranean and another $1,800 for the crossing. Until then, the child is held in one of Ghermay's warehouses. His frequent success in reaching deals in such strained circumstances seems largely based on his skills as a negotiator. "This is not robbery," says a Palermo police officer who asks not to be named. "It's dealing with people and dealing with trust. The more trustworthy Ghermay is, the more people will go to him."

Human Piggy Banks

Sicily, of course, is infamous for its organized crime syndicates. So the power and proliferation of people traffickers such as Ghermay raises the question: Why would the Sicilian Mafia allow them to make hundreds of millions of dollars on its turf? "The Mafia's peculiar interests are to control territory and control the economy," Licata says. "You can't imagine that an organization like that would be indifferent to the arrival of the people smugglers."

In December 2014, prosecutors in Rome had an answer. After arresting alleged mobster Massimo Carminati and 36 others in and around Rome, prosecutors issued a 1,200-page indictment that revealed their deep penetration into the city government, from contracts for garbage collection and park maintenance to vote rigging, extortion and embezzlement. On June 4, 2015, prosecutors arrested another 44 people as part of the same investigation. Most striking were allegations that Carminati's gang—which the prosecutors called Mafia Capitale, after its Rome base—was profiting from Europe's migrant catastrophe.

Mafia Capitale was not smuggling people, but once refugees arrived, it muscled in on the construction and management of the reception centers where the migrants were forced to live. According to the indictment, Carminati's right-hand man, a convicted murderer named Salvatore Buzzi, ran a social cooperative that provided services such as food and language classes for migrants, a business he claimed was worth $45 million. The indictment even accused Buzzi of fomenting anti-immigrant riots in Rome to encourage the state to build more migrant centers, where the foreigners would be safe. Lawyers for Buzzi and Carminati, who were not available to speak to Newsweek, have reportedly denied the allegations. But the prosecutors recorded Buzzi saying to an associate: "Do you have any idea how much I make from the immigrants? Even drugs aren't as profitable!"

An even bigger earner than Buzzi's cooperative was said to be a $110 million three-year contract to manage Europe's largest migrant reception center at Mineo in eastern Sicily. There, the managers were paid $32 per migrant per day to house and feed up to 4,000 residents. According to the indictment, as well as a separate investigation by prosecutors in the eastern Sicilian city of Catania, an official named Luca Odevaine coordinated the scam. Odevaine's various positions—deputy cabinet secretary in Rome, the designated immigration adviser at Mineo and a member of Italy's national coordination board on immigration—allowed him to skew Italy's entire immigration structure to serve Mafia Capitale's business interests. Phone taps showed how Odevaine would steer contracts for building and maintaining refugee centers to his associates, and then order that refugees to be sent to those centers, especially Mineo, filling it far beyond capacity. It was, said the prosecutors, not a system for receiving migrants but "a system of corruption."

The scale of the scam, and the manner in which its participants were exploiting one of Europe's gravest crises, shocked even those resigned to pervasive Italian corruption. Politicians were arrested. A former mayor of Rome resigned from his party position. But no amount of arrests, convictions or suspensions can resolve the daunting question the affair raises: If Europe's migration handlers are making money off the newcomers, and more migrants mean more cash for the Mafia and its corrupt political allies, is Europe actually fueling the crisis?

Dead Bodies and Broken Minds

Mineo migrant center is a collection of 403 redbrick houses in an isolated cluster in the middle of a broad valley. In a previous life, the camp was a U.S. military base, and with its checkpoints, razor wire fences and perimeter patrols, the place retains a restrictive feel.

There's no public transport here, and most of the migrants have no money. But during the day they are allowed out of the gates, and many choose to walk the country lanes that are now the outer limits of their world. Outside the gates today are John from Nigeria and Kadir from Ethiopia. John arrived 11 months ago after deciding Libya, where he had worked for three years, was too dangerous. Kadir arrived two years ago. Both men were told on arrival that they would have papers identifying them as refugees and asylum seekers in 35 days. Both had plans to move on to Germany. But when weeks turned to months and months became years, they came to a realization. "This place is a business," says John. "We are the business. The commodity. They keep us here and make money from us."

It was precisely that kind of state-criminal link that John says he traveled to Europe to escape. Even the $2.30 daily pocket money the migrants receive turns out to be another opportunity for migrant managers to profit off them. Rather than cash, the migrants are issued credit on an electronic card that can be used only in the shop inside the center or select markets outside. It sounds trivial, but this is a captive market worth close to $3.4 million a year. In Catania, Riccardo Campochiaro, a lawyer who works with migrant rights' group Center Astalli, described the migrants' extended detention at Mineo as a kind of stationary trafficking. His colleague, Elvira Iovino, adds that overcrowding means conditions are poor. And with no legal way to earn money, Iovino says Mineo has inevitably spawned its own illegal businesses: prostitution, drugs and traffickers offering an escape to northern Europe on the inside or work picking fruit for $11 a day on the outside. "Nothing," Iovino says, "nothing happens here without Cosa Nostra knowing about it."

Everyone benefits, it seems, except the migrants. John says the irony of risking death and using every last cent to travel thousands of miles to seek a better life, only to end up in a corrupt limbo, has broken minds in Mineo. You find them walking naked around the camp, he says. At least one has committed suicide. There have been riots and mass breakouts. John nods meaningfully at Kadir, who slumps against a car and squints at the horizon.

Kadir crossed deserts and oceans "to find some freedom." The great trek north took over a year. He walked in rags and flip-flops, doing whatever he needed to survive and pay for the next part of his passage. Along the way, he watched people die in the desert, in the war in Libya and on the boat across the Mediterranean. But after he arrived, he discovered it was all just more of the same. Big men and little people. The corrupt and criminal exploiting the honest and powerless. And Kadir is out of places to run to. "My life is still nothing," he says. "If I die here, I die. No problem."

It is that acceptance of death that most disturbs those on the front line of Europe's migrant crisis. Captain Giuseppe Margiotta has been sailing from Sicily to fish for prawns off Libya for 35 years. Lately, he has been dodging Libyan pirates, who may try to hijack his 100-foot boat, and rescuing migrants adrift at sea. On the night in April when 800 migrants drowned, Margiotta and his six crewmen arrived on the scene at 4 a.m. They pulled out the body of a 15-year-old boy. Then the sun came up and revealed a catastrophe. "Clothes everywhere," says Margiotta. "Children's clothes, women's clothes, men's clothes, flip-flops." Beneath the garments were bodies. Margiotta couldn't get over how alive they looked. Out of 800 passengers, the rescuers found 28 survivors and 24 bodies.

As he tells his story, Margiotta begins to cry. He cried that night too. "My men asked: 'Why?'" he says. He had not cried when his boat once sank or when a fire onboard threatened his family. "But when I saw this mess, children aged 10 to 15, picking them up like tuna out of the sea…" Margiotta catches his breath. When he resumes, he says he has a message for the leaders of Europe. People smugglers see migrants as a commodity. For politicians, they can be the same: something from which to make money or gain political advantage. "You [who] sit around the table and make decisions," says Margiotta. "You say you're civilized. But if this happens again, come and see for yourself. Come see what it means to see a carpet of people in the sea."

He wipes his eyes. "I cry because I'm raging."

Correction: An earlier version of this article misspelt the first name of Calogero Ferrara.